- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Last year's Patterns of Consciousness was a massive, ambitious, and occasionally dazzling psychotropic opus that sought to reshape consciousness through pattern manipulation, instantly establishing Caterina Barbieri as one of the most compelling contemporary synthesizer composers. Naturally, it will be a damn tough act to follow, but Born Again in the Voltage is not its highly anticipated successor, as its four pieces were recorded back in 2014 and 2015. On this more drone-based affair composed for the Buchla 200, Barbieri is joined by cellist Antonello Mostacci for a more modest and understated batch of songs. As such, Voltage is not quite as striking or distinctive as Barbieri's debut, but it is still quite good and "How to Decode an Illusion" is an absolutely gorgeous work.

Last year's Patterns of Consciousness was a massive, ambitious, and occasionally dazzling psychotropic opus that sought to reshape consciousness through pattern manipulation, instantly establishing Caterina Barbieri as one of the most compelling contemporary synthesizer composers. Naturally, it will be a damn tough act to follow, but Born Again in the Voltage is not its highly anticipated successor, as its four pieces were recorded back in 2014 and 2015. On this more drone-based affair composed for the Buchla 200, Barbieri is joined by cellist Antonello Mostacci for a more modest and understated batch of songs. As such, Voltage is not quite as striking or distinctive as Barbieri's debut, but it is still quite good and "How to Decode an Illusion" is an absolutely gorgeous work.

The album opens with its most slow-building and minimal piece, "Human Developers," which gradually takes shape around a core motif of distorted synth pulses with long decays.Soon after, Mostacci's cello takes over the foreground and a wonderfully moaning, shivering, and whining swirl of strings coheres, yet Barbieri's Buchla eventually makes a decidedly seismic resurgence.That is probably the most compelling part of the piece, as she whips up a shuddering earthquake of deep throbs that rumble up from the depths.That climax turns out to only be the piece's halfway point though.The second half emerges from that crescendo as a twinkling, cosmic fantasia of rapidly rippling arpeggios, buzzing chords, and vibrantly chirping electronics.It kind of feels like I am in an electronic aviary that is simultaneously hallucinatory and a bit too busy and cacophonous to be entirely comfortable.I am not sure if that is an entirely good thing, but it is certainly a unique headspace to inhabit for a while.The following "Rendering Intuitions" is considerably calmer, as it is built from a slowly churning bed of Mostacci's moaning cello drones.Gradually, a glacial and elegiac chord progression coheres and the piece achieves a kind of lurching, melancholy beauty.It is hard to tell what (if anything) Barbieri is doing performance-wise, as synthesizers are conspicuously absent, but her hand definitely shows in the layering and processing of the intertwining cello themes.In a purely textural sense, I am actually fonder of the warm and organic cello sounds than those of the Buchla, but the next piece shows that the latter can open up an absolutely sublime world of rich emotional depth in the right hands.

"How to Decode an Illusion" is a legitimate stunner, as Barbieri balances a slowly burbling, buzzing, and throbbing melody with bittersweetly swooping bloops and a vivid, haunting undercurrent of buried feedback, crackling noise, and distorted afterimages.It feels a lot like a beautifully heartfelt requiem penned by an android, but the bubbling forward momentum and vibrant textural dynamics create a perfect blend of light and shadow that prevents it from ever becoming a slog through sadness.In fact, it could very well be the most wonderful piece that Barbieri has released to date.After that triumph, the closing "We Access Only a Fraction" comes as quite a bizarre and candy-colored shock, resembling a relentlessly cheery, bubbling, and hyperkinetic synth pop freak-out.Or at least, it would sound like synth pop if it were not so maniacally busy and over-the-top.I truly do not know quite what to make of it, which I suppose is an achievement of sorts.In one sense, it is a bit annoying, but it is also transcendently bonkers, taking a mercilessly repeating simple theme and elevating it to over-caffeinated, tumbling lunacy.As a one-time experiment, its arpeggiated mayhem has some definite appeal, but a full album in that vein would be a borderline psychotic endeavor. I am relieved that Barbieri has thus far not opted to explore that direction further.

Aside from the questionable success of that final piece, however, Born Again in The Voltage is a strong and enjoyable album.Barbieri occasionally makes some unusual compositional choices, but they do seem like deliberate choices rather than flaws and the execution of her ideas is every bit as focused and vividly realized as her work on Patterns of Consciousness.The only real caveat with this release is that Barbieri's overarching aesthetic vision feels like it was still in the formative stages, as each piece on Voltage seems to pull in a different direction.That said, it was an unexpected delight to hear a cello composition from her.Moreover, Barbieri's talents as a composer were already quite formidable at this stage of her career, as "Illusion" is easily one of the best synth pieces that I have ever heard.While Patterns of Consciousness is unquestionably a more essential and visionary album than this one, Born Again in the Voltage is the more accessible and melodic of the pair.As such, it is a welcome addition to Barbieri's discography, offering a more instantly gratifying entry point for new fans than her more challenging, sprawling, and consciousness-warping 2017 epic.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

For years, I have rightly hailed Campbell Kneale as one of the true dark wizards of gnarled guitar noise, but I did not fully appreciate the depth and breadth of his vision until only recently: pre-Bandcamp, it was quite a difficult, expensive, and overwhelming endeavor to keep up with his sprawling body of work. As a result, several landmark albums fell through the cracks and remain woefully underappreciated to this day. One such example is this 2004 release on the now-defunct Scarcelight label, a hallucinatory suite of musique concrète, deep drones, and innovative collage that drew in a murderers' row of talented collaborators like John Wiese, Bruce Russell, Jonathan Coleclough, Peter Wright, and Neil Campbell. As with many Kneale releases, With Maples Ablaze occasionally dips into some nerve-jangling and dissonant territory, but the high points are legitimately amazing to behold.

For years, I have rightly hailed Campbell Kneale as one of the true dark wizards of gnarled guitar noise, but I did not fully appreciate the depth and breadth of his vision until only recently: pre-Bandcamp, it was quite a difficult, expensive, and overwhelming endeavor to keep up with his sprawling body of work. As a result, several landmark albums fell through the cracks and remain woefully underappreciated to this day. One such example is this 2004 release on the now-defunct Scarcelight label, a hallucinatory suite of musique concrète, deep drones, and innovative collage that drew in a murderers' row of talented collaborators like John Wiese, Bruce Russell, Jonathan Coleclough, Peter Wright, and Neil Campbell. As with many Kneale releases, With Maples Ablaze occasionally dips into some nerve-jangling and dissonant territory, but the high points are legitimately amazing to behold.

Scarcelight/Bandcamp

Kneale’s singular vision for With Maples Ablaze is one that defies easy description, but the first two of the album's ten untitled pieces do as good a job at laying out its enigmatic parameters as anything that follows.After a slow fade-in that sounds like a gentle wind rustling through a meadow, the opening piece unexpectedly comes alive with brooding metallic drones and a sputtering eruption of hums and blurts that sounds like someone fighting with a patch cord that keeps shorting out.That cryptic and somewhat unpromising opening salvo then abruptly segues into the more compelling second piece, which marries a chorus of cheerily chirping birds with buzzing, heavy drones that converge into a throbbing and see-sawing pulse.Curiously, however, the field recordings stay in the foreground for most of the piece, only gradually and partially becoming consumed by hallucinatory flourishes of chimes and a queasily undulating haze of overtones.For the most part, the rest of the album continues in a similarly elusive vein, casting a fragile and dreamlike spell that slowly dissolves from collage into drone and back again.As befits an album with such an unusual and fluid structure, Kneale and his collaborators were similarly unconventional in their choice of instrumentation.Even the most overtly musical bits (the drones) feel like they are emanating from rubbed glass, groaning metal, or spectral harmonics rather than actual struck notes.At other times, the sounds on With Maples Ablaze sound far more like someone throttling a large balloon animal in the empty hull of a vast cargo ship.Consequently, it feels like absolute supernatural sorcery when the album's many strange textures and motifs cohere into something richly harmonic and sophisticated, which first happens on the album's epic fourth movement.

It takes about five minutes to finally reveal its sublimely rapturous heart, of course, which is a rather masterful use of tension and deception.In any case, the vista that opens up is a truly gorgeous one, as Kneale combines a ghostly, vaporous haze of moaning melodies with a massive and shuddering edifice of shaking metal and warbling harmonics.It feels a lot like a haunted record player fading in and out of focus in a towering empty building that is shaking, swaying, and on the verge of collapse.In fact, it seems almost Biblical in its scope and beauty, like a non-hubristic Tower of Babel that is valiantly straining to reach the heavens despite the inexorable adversity of gravity.Of course, what Kneale was actually going for is anyone's guess, as the piece eventually transforms into a long, clattering field recording of a train pulling into the Hamburg station.Trying to find meaning in this album is probably a fool’s game, but Maples certainly whips up a wonderful illusion that there is something profoundly meaningful happening that remains maddeningly out of my grasp.

Naturally, Kneale felt there needed to be a counterbalance to that achingly gorgeous centerpiece, so the album’s next major piece is a nightmarish, disorienting plunge into gibbering bedlam that sounds like a loop of backwards, pitch-shifted pop music.If I had an extremely bad reaction to a psychotropic drug while at a rave in the Smurfs' village, it would probably feel a hell of a lot like "With Maples Ablaze VI."From there, things stay very goddamn lysergic and unnerving for a while, as the eighth section feels like a field of infernal cows lazily mooing near a lake of bubbling lava. Unexpectedly, however, the album closes with lengthy final act of immersive, dreamlike reverie (albeit with some friendly chickens thrown into the mix, as well as some creeping menace).The twelve-minute "With Maples Ablaze IX" is the album's languorous and lush false ending of sorts, as gently oscillating and slow-moving drones drift like heavenly clouds over distant sounds of clattering metal, chirping birds, twinkling wind chimes, and happy barnyard animals.It is a wonderfully warm and lovely piece, but it gives way to a more uneasy and ambiguous coda, as the lingering chimes are slowly consumed by a crackling and bleary haze of ringing metal and smeared, uncomfortably harmonizing drones.It evokes quite a surreal and enigmatically haunting tableau, like a solitary figure is quietly setting the forest ablaze around a small village as a church organ mournfully drones and a blacksmith hammers away in the distance.

The trajectory of With Maples Ablaze is not unlike sinking into an increasingly fractured and disturbing dream that opens up into an oasis of clarity once a crucial threshold has been reached...then having the slow realization that the oasis is actually a mirage.I was caught completely off-guard by how beautifully this album came together at the end, as there are definitely some lulls in the album where it feels like the narrative arc has been lost or derailed by indulgent bouts of abstraction.I suppose it is entirely possible that the thread was sometimes lost or that the album's trajectory gradually took shape organically, but it is far more significant that Kneale ultimately pulled the disparate threads together into something exquisitely satisfying.With Maples Ablaze is not quite a perfect album, but it is absolutely a unique one and some of the individual pieces are quite beautiful, brilliant, and deeply nuanced.Naturally, Kneale's many collaborators deserve some credit for the fascinating and ingenious directions that Maples takes, but he was the one that painstakingly assembled it into its complex and beguiling final form.Campbell Kneale took a leap into the unknown with this album and I have not heard anything else that resembles it before or since.Given the sheer volume of Kneale’s output, it is hopeless to guess where this release ranks in his vast discography, but I can confidently state that Maples is one of the more essential tips of an iceberg that I will be exploring for years.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Newly reissued, 2011's The Letter was Liberez's formal debut, but it is new to me and confirms that John Hannon's gnarled post-industrial vision was great right from the beginning. In some ways, I suppose The Letter is a bit more primitive than the shifting ensemble's more recent releases, but that is more of an asset than a shortcoming with this project–it simply means that Hannon and his collaborators sound even more like a bunch of early '80s experimentalists bashing on oil drums and chopping up tape loops in a freezing squat or abandoned warehouse. I suppose Hannon's more recent work is a bit more distinctive in some ways, often resembling some kind of Eastern European folk music played with rusted junkyard instruments and blown-out amps, but The Letter has enough visceral power, freewheeling experimentation, and unconventional percussion to stand out in its own right. It might actually be my favorite of Liberez's three albums, though Sane Men Surround is damn hard to top.

Newly reissued, 2011's The Letter was Liberez's formal debut, but it is new to me and confirms that John Hannon's gnarled post-industrial vision was great right from the beginning. In some ways, I suppose The Letter is a bit more primitive than the shifting ensemble's more recent releases, but that is more of an asset than a shortcoming with this project–it simply means that Hannon and his collaborators sound even more like a bunch of early '80s experimentalists bashing on oil drums and chopping up tape loops in a freezing squat or abandoned warehouse. I suppose Hannon's more recent work is a bit more distinctive in some ways, often resembling some kind of Eastern European folk music played with rusted junkyard instruments and blown-out amps, but The Letter has enough visceral power, freewheeling experimentation, and unconventional percussion to stand out in its own right. It might actually be my favorite of Liberez's three albums, though Sane Men Surround is damn hard to top.

The only true constant in Liberez's long and enigmatic history is John Hannon, but it could be said that The Letter's configuration of Hannon, Pete Wilkins, Nina Bosnic, and Tom James Scott represents the band's classic line-up.After all, The Letter was the album that put the project on the map after nearly a decade of self-released CD-Rs and the foursome held together long enough to produce 2013's Sane Men Surround as well.Obviously, Hannon's collaborators always play a significant role in shaping Liberez’s direction, but this "band" is first and foremost a studio project that chops, processes, and reshapes its raw material into hallucinatory and distorted collages.Naturally, it is damn near impossible to tell what anyone may have played, as everything is reduced to corroded textures, ghostly moods, and caustic snarls of noise.At the album's core, however, are some texts written by Bosnic (and presumably read by her as well).The album appropriately opens with a fragment of those writings, as a female voice that sounds like it is coming from an answering machine simply states "a letter."That is the entirety of the one-second "The Letter (Part One)," but fragments of that dispassionate, clipped voice continue to surface throughout the album, giving it a fever dream-like narrative thread of sorts.The album's first real piece, "_gag" also features a voice (male this time), but it sounds like someone is strangling a malfunctioning walkie-talkie.To Hannon’s credit, he manages to craft a nearly five-minute song out of those distressed eruptions of static, as the piece crawls slowly along over a hollow, repeating thrum and a hauntingly obscured undercurrent of chimes and simmering entropy.That entropy does not stay simmering forever, however, as it finally boils over and tears the piece apart in the final minute.Liberez excel at catharsis.

That vein of dreamlike, rhythmic hallucination ripped to shreds by howling eruptions of snarling noise is definitely a deliciously recurring one on The Letter.In fact, it resurfaces almost immediately with "Exercise Restraint," which marries a woody and plinking Eastern percussion motif with buried snatches of voice and a warbling drone, then burns it all to the ground with a churning explosion of roaring guitars and scorched trails of feedback.Sometimes Hannon is content to simply weave a surreal vignette without any towering cascades of noise though.The two strongest manifestations of Liberez's more nuanced side are both tucked away near the end of the album.The first, "Moved To Quell," is essentially just a ringing, percussive-sounding guitar motif that insistently repeats as an evocative fantasia of train sounds, drifting voices, and ravaged electronics bleed together in its depths.Elsewhere, the closing "Exercise Restraint (Part Two)" brings together an endearingly lurching groove, a woozily spectral pulse, an unintelligibly muddied monologue, and a quivering haze of harmonics.To my ears, it is the strongest piece on the album, but it gets serious competition from the blackened guitar squall and hammered metal percussion of "Atheist Rabble.""The Letter (Part Three)" is yet another highlight, resembling a disorienting pile-up of overlapping tape loops, moaning strings, and a sputtering chord that is desperately trying to force itself into the piece.

Given The Letter's initial limited, vinyl-only release on Luke Younger then-new Alter imprint, it is understandable that it did not make a big splash in underground music circles, but I am absolutely mystified about why this project is not appreciated far more seven years later.To my ears, it genuinely feels like Hannon has reignited the radical experimental zeitgeist of bands like This Heat, Einstürzende Neubauten, and Test Dept and taken it in a compelling direction all his own.I suppose those bands all had actual songs with vocals though, which may be a factor.And, more importantly, they all hit the scene at a time when post-industrial music felt genuinely vital and revolutionary.Liberez's rusted and scorched soundscapes were simply born at the wrong time, I guess.As far as I am concerned, however, this short-lived quartet got everything exactly right with their debut, achieving a beautifully executed mélange of unconventional percussion, broken-sounding guitars, explosive noise squalls, and chopped up mobile phone and cassette recordings that feels vibrant, visceral, and contemporary. Liberez are a refreshingly bracing and primal oasis in the current experimental musical landscape.I want sound art to be this raw, inventive, and intense again.Also, I bet Brion Gysin and William Burroughs would have dug this album.Something very cool is happening here–take notice.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

"In the wake of our recent 2xLP reissues of Radio Amor and Haunt Me, Haunt Me Do It Again, we're pleased to announce Tim Hecker's proper return to the label with a brand new full-length recorded in Japan utilizing a traditional gagaku ensemble: Konoyo. Worldwide release date is September 28th.

Hecker will also stage a series of special performances in tandem with the album's release in Tokyo, London, Krakow, and Berlin."

More information can likely be found here soon.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Swans' Soundtracks for the Blind, their last studio album released in 1996 prior to their 2010 reformation, will be released for the first time on vinyl by Young God Records on July 20th 2018. Much requested by Swans fans, the vinyl package will consist of four LPs in jackets enclosed in a box with a poster, insert and download card. The box set will be a limited edition of 4,000 copies worldwide and once sold out will be followed later in 2018 by a gatefold LP version. The album will also be reissued on CD featuring a repackage of the original digipak for the 1996 Atavistic release plus a bonus disc of the contemporaneous Die Tür Ist Zu EP (a German language version of some of the material from Soundtracks that also includes unique material) recently released for the first time on vinyl in the USA for Record Store Day 2018. Outside of the USA, Die Tür Ist Zu EP will be released as a limited edition companion piece double vinyl set, also on 20th July.

"This album has everything in there – all the ideas from Swans' initial 15 years of work. There's some contemporary recordings of the band as it existed in '96/7, with Larry Mullins on drums/percussion, Jarboe singing and playing keyboards, Vudi playing electric guitar, and Joe Goldring playing bass and electric guitar, and me singing and playing electric and acoustic guitar, but there's also a huge amount of sounds and recordings that Jarboe and I collected over the years. These are reassembled, looped, mangled, and in many cases overdubbed upon to create new pieces of music… I really set my own trap, dug my own grave on this one. There was SO MUCH material to deal with, to sift through (whole trunks full of decomposing, moldy cassettes and discs with samples and sounds), and the task of making it into something coherent was at times debilitating. Really like climbing up a mountain of sand. I don't remember why I set this goal for myself, to somehow incorporate such a ridiculously disparate amount of material. I think maybe it was so I could justify throwing all that crap into the local dump, which is what I did when I finished the album. But in the end, after centuries of picking at this huge iceberg of material with a toothpick, my trusty engineer Chris Griffin and I managed to sculpt something out of it. It actually breathes, seems to live, in most places I think. … When I decided to reform Swans in 2010 Soundtracks was what I referred to as a starting point" – Michael Gira / Swans 2018

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Fosil Sangiran is a previously unused pseudonym for the late Matt Shoemaker, who passed away in August 2017. Although he had a lengthy body of work under his own name, these works were to be issued under a different name as to reflect the differing intent he took during these recordings. Both of these cassettes consist of material that was recorded between 2012 and 2013 during Shoemaker's time living in Java, Indonesia, which is evident in the music itself. There are parallels to be heard to the work under his own name, but both Pasar Fosil and Khayal Kuno have distinctly different qualities, both in comparison to his other work and even between one another, but both represent differing facets to an artist that left us far too soon.

Fosil Sangiran is a previously unused pseudonym for the late Matt Shoemaker, who passed away in August 2017. Although he had a lengthy body of work under his own name, these works were to be issued under a different name as to reflect the differing intent he took during these recordings. Both of these cassettes consist of material that was recorded between 2012 and 2013 during Shoemaker's time living in Java, Indonesia, which is evident in the music itself. There are parallels to be heard to the work under his own name, but both Pasar Fosil and Khayal Kuno have distinctly different qualities, both in comparison to his other work and even between one another, but both represent differing facets to an artist that left us far too soon.

Shoemaker's work has always stretched the definitions of minimalism, a style that requires close attention and dedicated listening to fully appreciate, and that is the sensibility that resounds throughout these two tapes as well.The most obvious difference is the overall sensibility of the music, however.The oppressive heat of the jungle and the extensive history of Indonesia seep through, giving a humid, time-worn quality to the sound contained within.

Of the two, Khayal Kuno features more rhythmic experimentation from Shoemaker.The beginning moments of "Khayan Kuno – Bagian Satu" might not make this immediately apparent though, with its high frequencies echoing through a heavy bank of spring reverb, alternating between commanding and extremely quiet passages.Eventually some slow synth-like layers are blended in, filtered into a captivating, almost rotting-like sound that captures the historical setting in which Shoemaker recorded the material.Eventually he adds in some appropriately jungle filed recordings and rhythms resembling water dripping in a silent cavern.

On the flip side, "Khayan Kuno – Bagian Dua" is immediately more rhythmic, building from a far off rhythm that builds in volume and intensity throughout its first half.The rhythm is the focus with other elements taking the back seat.At around the halfway point, however, Shoemaker removes the beat, allowing what remains to expand in a more glacial, textural context.The sense of rhythm never disappears though, and the end reprises it via stripped down electronic pulsations and a nice bit of static accent.

samples:

Pasar Fosil is, by comparison, the more ambient and spacious experience.While it is not fully devoid of rhythm, the focus is placed more on texture and tone."Pasar Fosil – Bagian Satu" is the subtler of the two.An understated electronic expanse opens the piece, floating in a light ambient drift.The volume slowly builds and becomes a bit more commanding, but never becomes too harsh and retains its pleasantly looping haze throughout.

"Pasar Fosil – Bagian Dua" is a bit more forceful overall, but remains more in the realm of spaciousness than rhythmic.Building from a low rumble, he introduces some echoing pulses of unspecific sound, rattling through a metallic space.Much of the piece stays subtle; resonating through hollow, wide open environments that allow them to shine.Towards the conclusion, Shoemaker introduces some more forceful electronic blasts that come through aggressively, and while the closing moments are lighter, he pushes things into more shrill territories to keep things from becoming too placid as the piece ends.

Matt Shoemaker's work as Fosil Sangiran fits in with his consistently powerful solo discography, but it features a nicely distinct sheen that reflects the environment in which it was recorded.The differences between the two tapes complement one another very well, showcasing two different styles that reflect Shoemaker’s tragically shortened career perfectly.They may be archival releases, but this is obviously a reverential treatment of the material, courtesy of the Helen Scarsdale Agency, and one that is a fitting piece of his legacy.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Australia’s Todd Anderson-Kunert’s discography as a sound artist may have been relatively brief thus far (his earliest solo electronic work as Autonomous dates from 2007), but the quality has been exceptionally strong given his relative newness on the scene, and A Good Time to Go is no different. His blend of experimental electronics is an especially dynamic one that builds brilliantly from piece to piece on this tape, covering a wide spectrum of mood and diversity, while still functioning as a cohesive album.

Australia’s Todd Anderson-Kunert’s discography as a sound artist may have been relatively brief thus far (his earliest solo electronic work as Autonomous dates from 2007), but the quality has been exceptionally strong given his relative newness on the scene, and A Good Time to Go is no different. His blend of experimental electronics is an especially dynamic one that builds brilliantly from piece to piece on this tape, covering a wide spectrum of mood and diversity, while still functioning as a cohesive album.

One of the most striking aspects of A Good Time to Go is his focus on keeping the sound developing and evolving from beginning to end.Right from the opening "No.," this is obvious, with its deep, drum-like sounds stabbing aggressively through, leaving a trail of granular sounds and microscopic bits of sound.There is a sense of structure within the chaotic spaces, and a commanding shift once he brings in some expansive, thick low end bass sounds.Some more obvious synth moments are paired with abstract static bits to make for a strong mix of sounds, all done within the span of five minutes.The following "It's Taking Forever" continues to exemplify his penchant for bass frequencies, with a heavy rumble underscoring an overall audio creeping.He may work in some lighter, twinkling synthesizer passages, but the mood is kept dark via massive doomy thuds and sinister swells.The mix becomes sparser as it goes on, but the mood does not really lighten at any point.

For "A Moment to Have," he steers the composition into some more ominous territories.Slowly evolving textures are juxtaposed with silent passages as high frequency sci-fi sounds and some bizarre animal-like groans bore through the mix.There is an oddly natural, organic quality to the instrumentation that makes it even more unsettling.Sitting right in the middle of the running order though, Todd uses this as a transitional piece, with the mood becoming somewhat lighter from then on.

The buzzing interference and dying synths of "When, Now?" may not illustrate this shift too well at first, but within the noisier sections, Todd incorporates some cleaner tones and sounds. These eventually resemble a melodic progression, bringing a bit of light into the surrounding darkness.Percussive bits and a bleak electronic hum lead off "It's Ok," but on the whole there is more breathing room and openness throughout.The mood starts to become darker once again, however, with drum-like thuds echoing through like thunder, bringing along clouds of static to darken things back up as the tape comes to a close.

Within the span of a half hour, A Good Time to Go is a dense suite of songs that capture change perfectly.Todd Anderson-Kuner'’s composition and performance have a sense of unity from piece to piece, but they are constantly changing and developing from moment to moment.The change is a good thing, and never does it seem meandering or overly repetitive.The final product is an excellent balance between consistency and evolution, making for an excellent work from beginning to end.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The inimitable David Tibet returns to House of Mythology for a second inspired collaboration, this time teaming up with shape-shifting Italian ensemble Zu. Unlike his more spacey and indulgent union with Youth, however, Mirror Emperor feels very much like a Current 93 album. That similarity is not due to any lack of vision on Zu's part though, as this album is very much driven by a David Tibet in peak wild-eyed, apocalyptic prophet form: Mirror Emperor is essentially a fiery, hallucinatory, and poetic tour de force that drags Zu down a deep rabbit hole in the UnWorld on the other side of the mirror. As such, Mirror Emperor is a dazzling and compelling album primarily because Tibet had a vivid vision that he breathlessly shares with an incandescent passion. The music is often quite good as well, of course, but Mirror Emperor is more of a lysergic epic poem than a collection of discrete songs. That is just fine by me, as few things are more captivating than pure, undiluted Tibet with a microphone and some strong feelings to share.

The inimitable David Tibet returns to House of Mythology for a second inspired collaboration, this time teaming up with shape-shifting Italian ensemble Zu. Unlike his more spacey and indulgent union with Youth, however, Mirror Emperor feels very much like a Current 93 album. That similarity is not due to any lack of vision on Zu's part though, as this album is very much driven by a David Tibet in peak wild-eyed, apocalyptic prophet form: Mirror Emperor is essentially a fiery, hallucinatory, and poetic tour de force that drags Zu down a deep rabbit hole in the UnWorld on the other side of the mirror. As such, Mirror Emperor is a dazzling and compelling album primarily because Tibet had a vivid vision that he breathlessly shares with an incandescent passion. The music is often quite good as well, of course, but Mirror Emperor is more of a lysergic epic poem than a collection of discrete songs. That is just fine by me, as few things are more captivating than pure, undiluted Tibet with a microphone and some strong feelings to share.

David Tibet and Zu first met in Rome about seven years ago, but Massimo Pupillo has been a lifelong Current 93 fan, which seems to have made him an especially sensitive and thoughtful collaborator.I suppose it could be said that Mirror Emperor falls roughly in the same aesthetic territory as Myrninerest or classic Cashmore-era Current 93, as Zu largely devote themselves to ringing arpeggios, strummed acoustic guitars, and moaning cellos.Mirror Emperor sounds like something other than folk though, more closely resembling some kind of timeless and dreamlike chamber music.More importantly, Zu tend to wisely cede the foreground to Tibet, as he is a force of nature here and they mostly just needed to avoid stepping on his toes or breaking that otherworldly spell in order to create a great album (simply give Tibet a pen, step aside, and watch the fireworks).That said, Zu were not at all timid or one-dimensional–they were just very tactful about picking their shots and choosing when to allow their hallucinatory reverie to erupt into something more forceful.The most prominent Zu eruption comes quite early with "Confirm The Mirror Emperor," which resembles a sludgy and Sabbath-inspired metal groove that has been sucked dry by a vampire, leaving only a thick and sinuous bass line.That absence of distorted guitars leaves plenty of space for interesting activity in the periphery though and Zu made the most of it, embellishing the piece with woozily swooning slide guitar, shuddering cellos, and something resembling erratic, cascading autoharp ripples.Zu also take center stage in more subtle fashion on "The Heart of The Mirror Emperor," weaving a simmering and throbbing soundscape of electronics and tape loops.Eventually, the piece boils into a crescendo of quavering washes of distorted chords, yet it is otherwise one of the most tender and quietly beautiful pieces on the entire album.Notably, there is also a brief, brooding interlude of murky ambiance sans Tibet near the end of the album, but Zu are largely absent as well, as the piece is essentially just a brief glimpse into the howling void.

Most of the strongest pieces unexpectedly come near the end of the album.The first is the languorously lovely "(The Absence of the Mirror Emperor)," which wonderfully recaptures the magic of All The Pretty Horses-era Current 93.A lot of that success is probably because it is one of the few pieces on the album that feels like an actual song, as Tibet's near-spoken-word delivery crosses the line into fleeting and beautiful snatches of melody.Zu's accompaniment is especially inspired as well, as the strummed acoustic guitars are gorgeously embellished with a delicately ringing harmonic motif and quivering, hauntingly lovely snatches of cello. It also features the best closing line since Tibet dropped a "Sincerely, L. Cohen" on the Myrninerest album (this time, it is a snarled "Hey, was that the apocalypse?").The following "Before the Mirror Emperor" is another highlight, as Tibet sings a tender and lilting melody over a sublimely beautiful backdrop of chiming arpeggios, groaning strings, spectral drones, and buried field recordings.Elsewhere, the brief and hopeful "The Imp Trip of the Mirror Emperor" is similarly lovely, as Tibet sings a languorous melody over a dreamy web of rippling and quivering arpeggios.It is noteworthy that most of the best songs seem to have a hopefulness and innocence to them, as Mirror Emperor's premise seems to be a fundamental dark one.The album is considerably more complex and deliciously ambiguous than the broad outlines of its dark fable suggest, however, as the arc flows seamlessly and assuredly through passages of light, shadow, density, and delicacy.It never gets dark enough to be truly harrowing, yet it does achieve a sublime transcendence at points.No darkness is ever complete enough to fully smother beauty and wonder, even though it sometimes feels otherwise.

It is redundant at this point to observe that David Tibet is a iconic and oracular artist, though it is sometimes easy to take him for granted, as he has been releasing brilliant albums for decades.However, a bold vision and near-Biblical intensity alone do not always translate into immortal work, as the metaphorical stars still need to be perfectly aligned for a fresh masterpiece to be birthed.Happily, those maddeningly unpredictable and obstinate stars were quite close to their marks when Tibet and Zu came together, as this album is one of the most focused, consistent, and vividly evocative releases from Tibet in years.In fact, I suspect I will be finding hidden depths and meanings in it for months to come (especially once I splurge on the vinyl to get my hands on a lyric sheet).To borrow Tibet's own parlance, I am ecstatically OverMoon to announce that Mirror Emperor is an especially powerful Channeling.This is truly something deeper and more profound than a mere album–this is a vividly constructed world and mythology that mirrors our own, but shimmers with ageless dark magic and layers of sublime mystery.Years from now (if people still read), I truly believe David Tibet will be justifiably regarded as the reawakening of the lost visionary poet tradition.If he is not the modern day heir to Blake and his progeny, there simply isn't one.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Recorded during the turbulent period following the closure of beloved Denver DIY space Rhinoceropolis, Prayer Hands takes the hazy, melancholy dream-pop beauty of Like Author, Like Daughter and distills it into a gut-punch of simmering and seething emotion. While the swooning, elegantly blurred pop of "Angel" is probably the release's biggest hook, Madeline Johnston and collaborator Tucker Theodore gamely expand the Midwife aesthetic in some more visceral and experimental directions as well. The result is a near-perfect release that features three gorgeously haunting gems of hissing and hypnagogic shoegaze heaven in a row.

Recorded during the turbulent period following the closure of beloved Denver DIY space Rhinoceropolis, Prayer Hands takes the hazy, melancholy dream-pop beauty of Like Author, Like Daughter and distills it into a gut-punch of simmering and seething emotion. While the swooning, elegantly blurred pop of "Angel" is probably the release's biggest hook, Madeline Johnston and collaborator Tucker Theodore gamely expand the Midwife aesthetic in some more visceral and experimental directions as well. The result is a near-perfect release that features three gorgeously haunting gems of hissing and hypnagogic shoegaze heaven in a row.

The EP opens with the brief title piece, a dreamily warm and bittersweet web of rippling arpeggios that fades away after a couple minutes.While it ostensibly ends as a scratchy and unintentionally poetic answering machine message signals the start of the slow-burning "Forever," the two pieces feel like they segue together to deliciously prolong the gathering storm that finally breaks open when Johnston starts singing.While her vocals are characteristically melodic, tender, and languorously sensuous, they are doubled in quite a compelling and unique way.If I had to guess, I would say that the second layer of vocals are likely emerging from Theodore, but they are processed in such a way that they feel snarling and inhumanly infernal, lying somewhere between a rasping and demonic death metal howl and a strangled squall of white noise that seems to be supernaturally shaping itself into an approximation of a human voice.It is a wonderfully striking illusion.More than anyone else, Johnston seemed to have learned something crucial from Grouper, but found a way to do something new with it.While Johnston's vocals admittedly share Liz Harris's penchant for hazy reverb, the vocals on "Forever" do not sound like they are emerging from a fog so much as they sound like an unnerving interdimensional duet with a static demon.Few genres benefit from an infusion of visceral, otherworldly snarl more than dream-pop and shoegaze, as the tendency is to smother songs in too many effects or fall into the trap of thinking that the effects themselves are a song.With "Forever," Johnston and Theodore strike the perfect balance between slow-motion, soft-focus beauty and an undercurrent of screaming chaos.The vocal effects here simultaneously create a fog and viscerally tear through it.

Johnston's spectral double returns again for the more straightforwardly pretty "Angel," albeit in noticeably muted form, as her lilting vocal melody merely swirls through a haze of crackle and hiss.As with "Forever," it is an absolutely lovely song, but it is a much more benign one–it feels like a break-up song that is more of a tender reminiscence than a raw wound (and nothing supernatural seems to be trying to claw its way out of my speakers).In particular, Johnston and Theodore do an especially stellar job at fleshing the piece out with subtle layers of depth and color, gradually evolving from gauzy, shimmering guitar noise into a lovely coda that transforms the piece into a charming bit of sun-dappled backporch psychedelia (all the distortion falls away to leave only a lilting slide guitar melody, a strummed acoustic guitar, and a slow pulse of swelling reversed chords).Naturally, a piece entitled "Angel" has to be followed by a counterbalancing piece entitled "Demon," leading Prayer Hands into its droning, experimental and wonderfully hallucinatory final act."Demon" slowly fades in on a wave of tape hiss that sounds like waves cresting on a beach, but moaning layers of unintelligible backwards vocals gradually start to converge into a slow pulse.Soon after, that surreal tape loop miasma starts to shape itself into soaring and whooshing vocal flourishes and the guitar and drums finally kick in, dragging the spacey, undulating soundscape into a woozily beautiful instrumental swirling with buried melodies and intertwining, serpentine solos.In essence, it is a total psych-rock freak-out, Midwife-style: a glacial unfolding feast of seething layers and masterfully controlled, slow-building tension that never fully boils over.

With Prayer Hands, Midwife has officially entered the exclusive pantheon of Artists Who Have Floored Me Twice, as Madeline Johnston retains everything that was wonderful about her debut, but eliminates absolutely everything that diluted the cathartic power at the project's core.There is much to love here, as Johnston intuitively and organically stretches and reshapes conventional song structures to serve her slow-motion beauty perfectly and even the darkest stretches are alive with passion and melody.Moreover, she has crafted a moving elegy for an entire community (as well as an unintended one for a close friend) that feels like a transcendently great, soulful, and vibrantly alive dream-pop album.That is no small feat.In fact, Prayer Hands favorably reminds me of a half-remembered Charles Bukowski quote about why he was bored by Albert Camus: he preferred writers who screamed when they burned (existentially, not literally).Though I am sure that I totally mangled the quote, the sentiment has stuck with me for decades, as the world is full of art that buries its raw emotional core in mannered artifice.Midwife definitely does not fall into that trap, as Johnston's vision is a volcano swathed in dreamlike fog.This is everything I could possibly want in an EP: great songs, heartfelt intensity, depth, and plenty of unconventional ideas executed masterfully.Prayer Hands is easily one of my favorite releases of 2018.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This unique album quietly surfaced back in April, but it is one of 2018's most wonderfully unexpected releases, as it is the first of Landes Levi's recordings to ever be made widely available. Although she has amassed a small cult following through her releases on Belgium's Sloow Tapes, Landes Levi has largely remained an obscure figure in music circles, rarely recording and jokingly describing herself in a recent Wire interview as a "street musician made good." It would be more apt to describe her as reluctant drone royalty, however, as she co-founded The Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company in the '60s, an ensemble that also included folks like Terry Riley and Angus MacLise. She also studied with La Monte Young and an improbable host of legendary Indian musicians over the years. On IKIRU, Landes Levi is joined by luminaries of a different sort, as her haunting sarangi melodies are backed by Belgian underground veterans Bart de Paepe and Timo von Luijk. IKIRU would have certainly been a mournfully lovely album with just Landes Levi's unadorned sarangi playing, but her sympathetic collaborators take her viscerally elegiac vision into wonderfully ritualistic and hallucinatory deep-psych territory.

This unique album quietly surfaced back in April, but it is one of 2018's most wonderfully unexpected releases, as it is the first of Landes Levi's recordings to ever be made widely available. Although she has amassed a small cult following through her releases on Belgium's Sloow Tapes, Landes Levi has largely remained an obscure figure in music circles, rarely recording and jokingly describing herself in a recent Wire interview as a "street musician made good." It would be more apt to describe her as reluctant drone royalty, however, as she co-founded The Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company in the '60s, an ensemble that also included folks like Terry Riley and Angus MacLise. She also studied with La Monte Young and an improbable host of legendary Indian musicians over the years. On IKIRU, Landes Levi is joined by luminaries of a different sort, as her haunting sarangi melodies are backed by Belgian underground veterans Bart de Paepe and Timo von Luijk. IKIRU would have certainly been a mournfully lovely album with just Landes Levi's unadorned sarangi playing, but her sympathetic collaborators take her viscerally elegiac vision into wonderfully ritualistic and hallucinatory deep-psych territory.

As with all Oaken Palace releases, IKIRU ("to grow") is an album with a deep sense of purpose, as the label exists to donate all of their profits to environmental charities.The inspiration for this particular entry in the series is the declining population of Monarch butterflies, which gets explicitly addressed with an excerpt from an Ira Cohen poem at the beginning of "Butterfly Brain" (Landes Levi is primarily a poet herself).For the most part though, IKIRU has the otherworldly feeling of a timeless ceremony in a remote and ruined temple.Aside from that brief spoken interlude, both of the sidelong pieces that compose IKIRU are quite similar in structure, unfolding as achingly beautiful sarangi solos that alternately moan with anguish and transcendently blossom into ephemeral snatches of soaring melody.I suspect these pieces were both improvised around a loose central motif rather than composed, as there are occasional stretches were the sarangi falls silent or blends into the background, yet Landes Levi's playing is deeply evocative, affecting, and sublime–her melodies often feel like a darkly lovely and heartfelt requiem for all of life on earth.That said, it is not an oppressively sad album by any means.Instead, it feels like something quite novel: a languorously unfolding dreamscape that billows outward from a heavenly melodic thread that winds through it like a stream or a drifting tendril of opium smoke.

While IKIRU is ostensibly a Landes Levi solo release, the contributions of de Paepe and van Luijk play a crucial role in crafting album's beguiling spell.Occasionally, the pair creep into the foreground with a brief zither melody, but primarily focus themselves on crafting a ghostly and ceremonial sounding backdrop for Landes Levi's lyrical melodies to elegantly float, twist, moan, and churn through.On the opening "Butterfly Graveyard," for example, the duo use thundersheets to create a deep, gong-like pulse.There are also occasional accordion drones that billow up from the depths, as well as a strange and fascinating layer of field recordings.I would love to know where and why the recording was taken, as it seems to have nothing to with butterflies.Or maybe it does, as it is very easy to imagine that the quiet sounds of butterflies would be eclipsed by most other natural sounds, no matter how many are present (a vast, fluttering cloud of butterflies could easily be drowned out by a single insistent bird).In any case, the natural sounds are weirdly perfect in this context, as the deep exhalation-like whooshes and the chorus of jabbering woodland creatures contribute beautifully to the piece’s deeply meditative feel and sense of place.No little animal friends join the trio on the more nocturnal and dreamlike "Butterfly Brain," sadly, but they are replaced by a spectral trail of blurry and uneasily harmonizing mellotron drones from van Luijk.The percussion is quite different as well, as the lingering gong-like tones have a submerged feeling that evokes a secret underwater grotto.Both pieces are absolutely wonderful and complement each other nicely.

In hindsight, it is very easy to understand why Landes Levi has had such a sparse and elusive recording history, as she has spent much of her life traveling extensively, studying Indian music and poetry, translating, and writing prolifically.Also, the world has not exactly been clamoring for solo sarangi albums or Eastern devotional music, though appreciation for the pioneering work of kindred spirits La Monte Young and Catherine Christer Hennix has happily increased in recent years.Consequently, it is the perfect time for Landes Levi to finally claim her place in the pantheon of Eastern-influenced drone luminaries.Musically, Landes Levi is not unlike an orchid: she is excellent musician, but she needs exactly the right environment for her art to blossom into something strikingly beautiful and unique.With de Paepe and van Luijk, she found precisely that and her vision fully blooms with IKIRU.Louise Landes Levi is a singular person and this album is the one that finally befits that.Of course, I also loved her 2014 collaboration with Christer Hennix (From The Ming Oracle), but IKIRU is on a different plane altogether, easily ranking among the strongest and most memorable albums that any of the three participants have ever been involved in.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

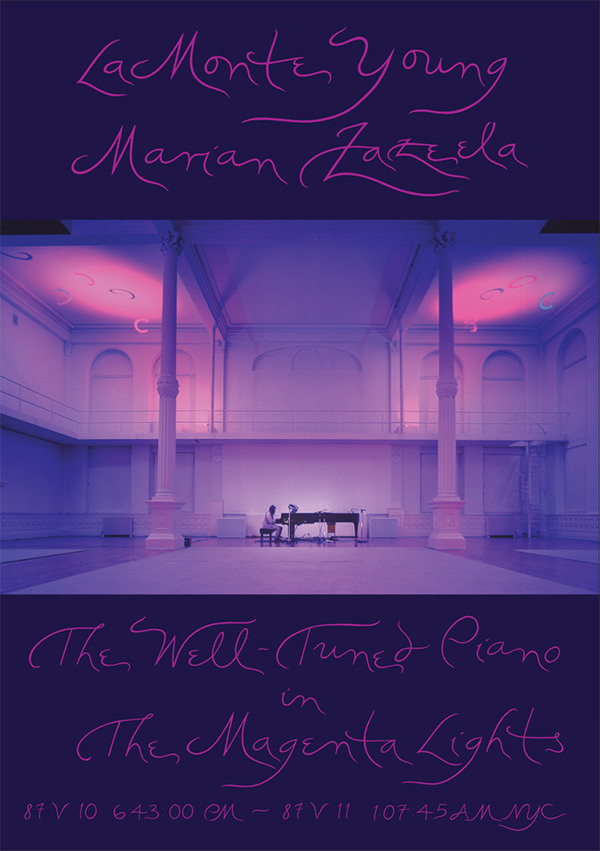

"Deluxe DVD edition of The Well-Tuned Piano in The Magenta Lights, containing La Monte Young’s continuous 6 hour-24 minute performance of his masterpiece is now back in print for the first time since 2001. Comes with a 52-page booklet, which includes La Monte and Marian’s essays on their works. Edition of 500, one time pressing.

High Minimalism - one of the great, revolutionary musical movements of the 20th century, is marked by a canon of towering and iconic works - Dennis Johnson's November, Riley’s In C, Conrad’s Four Violins, Reich's Drumming, Palestine’s Four Manifestations On Six Elements, Wada’s Lament For The Rise And Fall Of The Elephantine Crocodile, the list goes on. Even in the face of these marvels - the radicalism and wonder, little comes close to wild ambition of La Monte Young's great, evolving masterpiece, The Well-Tuned Piano - among the most beloved works in the body of Minimalism's output. Initially recorded in 1981, issued as a now impossibly rare 5LP set in 1987, Young’s continuous 6-hour-and-24 minute performance of the work was recorded again in 1987 and released as a DVD in 2000, with the new subtitle, In The Magenta Lights, going quickly out of print and remaining so ever since. Now, in a momentous event, the composer’s own MELA Foundation and Just Dreams recordings have issued a new deluxe DVD edition of The Well-Tuned Piano in The Magenta Lights, making it available to the public for the first time in nearly 20 years. This is as big as it gets.

Begun in 1964 and premiered ten years later, The Well-Tuned Piano, despite its consuming and immersive duration, is regarded by Young to be an unfinished work, slowly evolving in his hand, mind, and ears over the decades. Utilizing his own just-intonated tuning system, divided into seven structural / thematic intervals of varying length, the work, being improvisation, is ever-changing with no specific form. Considered by many to be among the great achievements of 20th-century music, it is one those rare works which is known by almost every fan of avant-garde music, while having been heard and seen by comparatively very few - the Gramavision release being virtually unobtainable, the initial DVD having been only issued in an edition constrained to the low hundreds, and performances having been scarce at best.

This realization of The Well-Tuned Piano In Magenta Lights was recorded and filmed in concert May 10, 1987, at 155 Mercer Street, New York City, with the subtitled referring to its accompanying light-installation by Marian Zazeela, Young's partner and collaborator since the early 1960s. A work of shimmering sonority, challenging relationships, The Well-Tuned Piano deserves every bit of its legendary status - an entire rethinking of the way the piano is seen, understood, and heard, singing down the decades since its early versions began to appear.

Issued by the composer himself, this new edition expands the original accompany booklet, including La Monte and Marian's essays on their works, to 52 pages with a new essay by their senior disciple Jung Hee Choi. For the first time, in these notes, Jung Hee illuminates the the tuning underlying this masterpiece of composition, for all to understand. This issue of The Well-Tuned Piano In Magenta Lights is as important and as essential as they come. 6 hours and 24 minutes of pure bliss. It won't sit around for long. Who knows if we'll see it again before another 20 years."

-via Soundohm

More information can be found here.

Read More