- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The Sky With Broken Arms is a further step ahead into the realm of the unknown, where the music made of minimal, dreamy guitar chords and eerie wordless vocals over a dense layer of crackling noise comes out of a strong conceptual idea.

As Roberto Opalio’s foreword to the work reads "On a winter day two years ago, I found out that an entire section of my vinyl collection was completely ruined by an inexplicable oxidation process. [..] As a first reaction, I decided not to play those records ever again... and that I did, for a long time. 'Til one night, exhausted, I felt the absolute urgency to listen to one of those LPs whose musical content got buried by the vinyl surface noise. In that moment, the shocking epiphany: [..] slowly, I began to perceive that not only were the old, beloved sounds that I was used to still there, but the layer of ground noise obliged me to even more attentive and active listening; thus I was discovering very subtle sound details now claiming their own being and pretending their own space. The idea of a new MCIAA album came out of this enlightenment. A new concept concerning the representation of music on the one hand and its perception on the other. A music so essential and precious as to be discovered by the listener little by little, because hidden by a blanket of crackling noise, which I obtained from the blank grooves of my damaged vinyls. Thus, here we are: infinite spaces of disintegration and psycho-existential ecstasy… essentially, spaces of non-limited, non-stoppable Poetry."

Out March 7th on Elliptical Noise.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Northern California producer Fred Welton Warmsley III's solo work as Dedekind Cut (pronounced "dead-da-ken cut") has evolved from fractured industrial design into increasingly subdued and sublime ambient meditations across two years of dedicated activity. His second full-length collection, Tahoe – so named after the mountain lake town he now calls home – swells with widescreen grandeur, evoking vistas both inner and outer. There are echoes of his earlier, more tempestuous mode in tracks like "MMXIX" and "Spiral" but overall the album skews panoramic and pensive, muted synthetic mists contoured with choral melody, field recordings, and radiant drone. His compositional instincts feel alternately classical, contemporary, and conflicted, befitting an artist whose discography spans divergent labels.

Warmsley characterizes Tahoe as a "time peace," sifting through "the past, the present, future, and fantasy."

Out February 23rd on Kranky.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Norway's Kristoffer Oustad and the Finnish duo of STROM.ec (Jasse Tuukki and Toni Myöhänen) are no stranger to dreary, aggressive electronic music, so a collaboration between the two comes as no surprise. I have some familiarity with both artists and I have been a fan of everything I have heard from them so far, but it was rarely surprising or unexpected in sound. With these two projects coming together, however, the final product stands out even more uniquely than their solo material. New Devoted Human is richer, more complex, and more fully fleshed out than I expected, and has an impressive amount of depth and complexity that is strong and memorable on all fronts.

Norway's Kristoffer Oustad and the Finnish duo of STROM.ec (Jasse Tuukki and Toni Myöhänen) are no stranger to dreary, aggressive electronic music, so a collaboration between the two comes as no surprise. I have some familiarity with both artists and I have been a fan of everything I have heard from them so far, but it was rarely surprising or unexpected in sound. With these two projects coming together, however, the final product stands out even more uniquely than their solo material. New Devoted Human is richer, more complex, and more fully fleshed out than I expected, and has an impressive amount of depth and complexity that is strong and memorable on all fronts.

Of course the album is jam packed with distorted static and bleak passages of funereal drones, but the trio's use of more conventional song structures and instrumentation is what gives this record its distinctive sound and overall song to song diversity.Opener "Inherent Resurrection" is at first the expected overdriven synthesizers and menacing hum, but once the big, multilayered rhythms come in, the feel shifts more to a heavily distorted, noise laden take on EBM.Nothing here would be appropriate for a goth club of course, but it has a great, memorable sense of structure and rhythm.

"Fever Wave Dream Function" sees the trio retaining some of this mood but within a slower tempo.Melodic synth pads creep from the background, but explosive drums and bass heavysequences take center stage.A wide array of styles appear throughout the title song as well:power electronics style yelled vocals are blended with big, industrial drums and rhythms, but all augmented by some at times beautiful ambient synthesizer works.The standard ranting, screaming and aggression does take more of the focus throughout the album, but that is not necessarily a bad thing.For "Blood Consciousness", the angry and malicious vocalsare hard to fully decipher are mixed with harsher, brittle passages of noise and distortion.Even within all this chaotic violence, however, there is a clear sense of structure and organization.Similar styled vocals appear throughout "Reluctant Traveller" (by guest vocalist Grutle Kjellson), but within a diverse mix of crashing rhythms, jarring noise, and at times what almost sounds like a guitar appearing occasionally.

The less harsh moments of New Devoted Human are also memorable as a bit of pleasantness in this otherwise swirling maelstrom of chaos.Symphonic touches appear throughout "Nattsvermer," with the heavy drama enhanced by some unconventional programmed rhythms.The piece never goes into overtly aggressive territories, and actually has a rather pretty conclusion.Album closer "Kosto" also sees the trio working in some neo-classical bombast and structures, but its final moments finish the album on a rather light, almost uplifting note.

Extra kudos should be given to the Malignant label for issuing New Devoted Human on both CD and vinyl.Besides the latter's more luxurious presentation, the analog mastering gives an even more pronounced depth and richness to the album, elevating it as the strong artistic statement it is.Oustad,Tuukki, and Myöhänen may not have intended to create an album with any sort of human warmth to it, but it is there, lurking beneath the cacophonous rhythms and ranting vocals, and that edge makes for quite a standout piece of intentionally ugly music.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Both Kazuma Kubota and Mei Zhiyong are relatively new to the realm of harsh noise, but they have individually worked with some of the biggest names associated with the genre, such as Macronympha, Torturing Nurse, and Kazumoto Endo (among a multitude of others). This collaborative session is refreshingly no frills and stripped to the barest foundations of what traditional noise is and should be, and at a time in which so many artists are stepping away from the style, it is wonderful to hear something that is as classic and timeless as this.

Both Kazuma Kubota and Mei Zhiyong are relatively new to the realm of harsh noise, but they have individually worked with some of the biggest names associated with the genre, such as Macronympha, Torturing Nurse, and Kazumoto Endo (among a multitude of others). This collaborative session is refreshingly no frills and stripped to the barest foundations of what traditional noise is and should be, and at a time in which so many artists are stepping away from the style, it is wonderful to hear something that is as classic and timeless as this.

Session June.12.2016 is just that:a recording of Kubota and Zhiyong together working their array of electronics and distortion pedals to create relentless, amelodic sheets of noise and at times piercing, painful tones.The stripped down feel carries into the simple packaging:a plain white sleeve, without any artwork or additional details that is fitting for the unedited, untreated recording that it adorns.Having thrown myself deep into the harsh noise world in the mid and late 1990s, this looks and feels like something I would have randomly ordered via a mailorder like Relapse or Anomalous without fully knowing what I would be receiving, but being very satisfied with myself once it arrived.

The duo waste no time in the performance, immediately blasting in shrill and stuttering electronics, with harsh, distorted stabs cutting in to end any semblance of conventional structure or sound.Cuts and edits are violent and jerky, building into painful walls of noise and then cutting them away to more jarring, jagged soundscapes.It is hard to ignore the influence of the classic practitioners of the genre:Kubota and Zhiyong go from the cut-up pseudo-rhythms of Pain Jerk, the manic stop-start structures of Masonna, and the multilayered sheets of noise pioneered by the Incapacitants.The performance never comes across as an emulation of any of these legends, but instead it feels like intentional, reverential nods in their direction.

Across the 45 minute session the two never let themselves fall into monotony:shrill, painful high frequencies are soon replaced with massive, foundation shaking low end bursts.Textures resembling rushing waves and sputtering computers appear, as do some nearly psychedelic passages of phaser and flanged layers of static.There is a sense of movement and activity throughout, but also a feeling of consistency and focus.Even with all of these changes, it never feels like Kubota and Zhiyong are just letting the machines do all the work, but that they are actively shaping and structuring the chaos.After a chirp-heavy build it seems to herald the end, with the layers of noise stripped back for the sake of sparser passages, but there’s one last shrill and bass heavy burst left before the two call it quits.

Kazuma Kubota and Mei Zhiyong admittedly are not breaking any new ground on Session June.12.2016, but that is not the point.With so many of the well-regarded noise artists either drastically slowing down activity or branching into less abrasive, more musically tinged work, it is simply refreshing to hear an unadulterated pure noise record.No pretense, no attempts at being provocative, simply a disc of extremely varied, high quality noise.It may not be anything wildly unique or innovative, but it is pure comfort food to an old school noise fan such as myself.

samples:

- Session June.12.2016 [Excerpt One]

- Session June.12.2016 [Excerpt Two]

- Session June.12.2016 [Excerpt Three]

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The artwork and title of this new tape captures the vibe that Vanessa Rossetto conjures up early on rather well: a sort of 1980s damaged mélange of consumerism and high art that is as visceral and to the point as it is conceptually high-minded. What follows is a complex mix of electronic composition, treated field recordings, and who knows what else, making for a wonderfully nuanced, extremely compelling cassette of equally beautiful and abrasive sounds.

The artwork and title of this new tape captures the vibe that Vanessa Rossetto conjures up early on rather well: a sort of 1980s damaged mélange of consumerism and high art that is as visceral and to the point as it is conceptually high-minded. What follows is a complex mix of electronic composition, treated field recordings, and who knows what else, making for a wonderfully nuanced, extremely compelling cassette of equally beautiful and abrasive sounds.

The title and artwork are most closely tied to the opening piece, the 11+ minute "Sample Sale."An array of stuttering musical loops full of schmaltzy electronics best resembles an ancient tape of mall musak in its final state of decay, as what could be fragments of shoppers conversing are peppered throughout.Within all of this Rossetto tastefully places layers of static and additional field recordings with various levels of processing.Disorienting loops eventually relent to a unrecognizable bed of noise, before finally concluding on passages of found sound and a far off television droning away.

The other lengthy work that concludes Fashion Tape, "Measurement" (with Matthew Revert) has all of the complexity of "Sample Sale," but structurally is more focused, and less collage-like overall.Rossetto delivers spoken word mostly of the piece’s title, as Revert adds in strange passages of repeated and recited numbers via a disconnected, monotone voice.Behind this there are lush cello-like passages that underscore the piece, adding a bit of melancholic beauty to the otherwise clinical spoken parts.However, she chooses to throw in some power tool recordings to blow up the composition’s more melodic tendencies; a drastic misdirection that I found quite enjoyable.

The shorter pieces between these two larger bookending works also do an exemplary job at capturing the varieties of sound Rossetto has been working with since her earliest releases."Memphis Milano" is a basic, but well crafted short piece of buzzing nasal electronics.Structurally it is not overly complex, but she does a great job at keeping it varied via ever changing volume shifts and dynamics."Fake Cheese" features more use of field recordings, multilayered and with treated pitches done just enough to make the sounds feel unsettling and unnatural.By the end she pushes the piece into dark ambient territory and with the addition of sinister whispers and overdriven digital noise, it builds into a bleak conclusion."Radiant Green" stands out via frequent use of some southern sounding gentleman discussing how he is seeing colors, as Rossetto weaves in layers of strange processing and random sounds.The final moments build to an amazingly aggressive volume shift that is reminiscent of (and likely as dangerous to speakers as) Whitehouse's "Torture Chamber."

Rosetto's exceptional ability at reworking field recordings and utilizing unspecific, but fascinating electronics run through this entire tape.There is a joyous disregard for genre boundaries and styles here as well, as within the same piece I felt the use of intentionally abrasive, chaotic passages as well as precisely focused works that are as compositionally tight as any formally trained academic is likely to produce.It is a weird, but unquestionably wonderful journey from beginning to end.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Recently reissued, this unusual EP/mini-album was originally composed as a continuous hour-long piece for the French radio program Atelier de Création Radiophonique. The adventurously narrow theme of the endeavor itself is the unusual part, as the entire program was created from sounds generated from antique music boxes. Given that extreme constraint, this material was never intended to be formally released as an album, but Leaf liked these alternately surreal and playful experiments enough to release it anyway (albeit in somewhat altered form). When it was first released back in 2006, this modest release felt somewhat slight and anticlimactic in the wake of Colleen's classic first two albums, yet I have gradually warmed to it quite a bit over the years. While I still think much of this release is strictly for devout fans, it would be a mistake to overlook it completely, as it features a couple of woefully underheard gems.

The original version of Boîtes À Musique that Cécile Schott composed was a longform collage in which the individual vignettes were bridged together by music box-themed movie samples.Consequently, the altered shape of this album was driven by necessity, as obtaining the rights for all of those film snippets would likely have been a logistical and financial nightmare.As a result, the album is comprised of fourteen discrete pieces of varying lengths that range from under a minute to almost seven minutes.Notably, one of the longest pieces, "I'll Read You a Story," is a reprise of one of the most sublimely gorgeous pieces from The Golden Morning Breaks.In fact, it is one of the most quietly stunning pieces that Schott has ever recorded, so it is a lock for one of the highlights here as well.I supposed its inclusion could be seen as cheating a bit, but Schott never intended for this album to be released and it made perfect sense for her to conclude her radio session with such a dazzling crescendo.In any case, I am always happy to hear it again.In fact, I suspect it was the primary inspiration for this deeper plunge into the world of music boxes.The marriage is certainly a good fit, as the delicate, wistful prettiness of music box melodies is not a far cry from the delicate, wistful beauty of Colleen's other work.

Notably, this is not Schott's first dip into her friend John Cavanagh’s collection of Victorian music boxes, as Golden Morning’'s "The Heart Harmonicon" originated there as well (albeit from a recording made by Cavanagh himself).Back then, music boxes played a small role in Colleen's aesthetic, but Boîtes À Musique makes Cavanagh's collection the sole focus…sort of.There are a few exceptions and "Story" is one of them for a couple of reasons.For one, its dreamily chiming central theme is fleshed out considerably by Schott's classical guitar accompaniment.Secondly, much of the bittersweet beauty of "Story" is due to her transformative production wizardry, as the piece is a languorous swirl of backwards melodies, rippling arpeggios, and flickering hallucinatory flourishes.Schott takes a similarly loose thematic approach with the album's other centerpiece, "Your Heart is So Loud," which stretches and blurs a fragile melody to leave a heavenly shivering wake of afterimages.Though much shorter, "The Sad Panther" is also quite beguiling, unfolding as a slow-motion cascade of hazy backwards melodies.Despite their superficial differences, both "Panther" and "Heart" ultimately achieve the same aesthetic end, feeling like a time-stretched and lovesick tableaux unfolding within a dream-like snow globe world.

If the rest of Boîtes À Musique had deepened and expanded that vein, it would have likely been Schott's third stellar album in a row, but the remaining pieces are a bit more varied, whimsical, and sketchlike.The better ones are quite charming though, particularly the stumbling and fitful rendition of "Happy Birthday" that comprises "Charles's Birthday Card."In a similar vein, "A Bear is Trapped" sounds like an obsessive child maniacally trying to play "Pop Goes the Weasel" on a rusty music box that sounds like it is hemorrhaging crucial parts as the crank is enthusiastically wound too quickly.Elsewhere, both "Under The Roof" and "Bicycle Bells" are awkwardly pretty, as tumbling melodies of ringing notes unfold at an erratic pace.There are also a couple of smaller themes that stake out their own small parts of the album: a pair of gamelan-themed pieces and a pair of componium pieces (appropriately titled "What is a Componium?").The latter are some of the more substantial works among the idiosyncratic mixed bag of remaining pieces, particularly "What Is a Componium?Pt. 2," which is an undulating tapestry of sweeping, overlapping, and crystalline arpeggios.There is also one particularly bizarre and aberrant piece near the end, the cheerily pixelated "Calypso in a Box," which sounds like it could be the mercilessly annoying theme of a video game geared towards small children.I am not sure if that one necessarily counts as a misstep, however, as its brief candy-colored lunacy is certainly an effective palette-cleanser after the lovely "Your Heart is So Loud."I doubt many tears would have been shed if it had been accidentally omitted from the reissue though.

Obviously, it would be wonderful if every piece on Boîtes À Musique sank deeper into the warmly enveloping dream-state conjured by pieces like "The Sad Panther," but it is still an interesting, unique, and divergent release in its existing form.Schott would have been crazy to pass up an opportunity to step outside her usual working method and dive into a roomful of delightful Victorian contraptions.In hindsight, most of my previous grievances with this EP stem from a simple misunderstanding: I wanted Schott to make my new favorite album and she wanted to see if she could turn a treasure trove of antiques into a compelling hour of radio.She won (understandably).The important thing is that Boîtes À Musique maintains the fundamental mystique and endearing anachronism of the Colleen aesthetic and that this fleeting departure resulted in a couple of gorgeous new pieces that would not have otherwise existed.It may be a minor release within Schott's frequently brilliant discography, yet it is a minor release that unexpectedly hits some impressive heights every now and then.If this album can be said to have a significant flaw, it is merely the unavoidable one: all of these pieces have been decontextualized from their intended role in a larger piece.As such, less substantial pieces that once filled a crucial place in a continuous flow are lamentably isolated and presented as individual works.Understandably, they wilt a bit under that kind of scrutiny, even if it is not their fault.Hopefully, the original broadcast will someday reappear through the magic of the internet and belatedly right that wrong, but until then "The Sad Panther" and "Your Heart is So Loud" make great consolation prizes.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

According to legend, this enigmatic Serbian composer became deeply interested in music as a means of trying to recapture the sounds of the metal factory that he had worked at in Belgrade. If this 2016 collection of his early cassette releases succeeded in that aesthetic objective, that factory must have quite a terrifying edifice, as the best pieces evoke a relentless and pummeling mechanized horror akin to Fritz Lang's Metropolis. More importantly, some of these songs are absolutely mesmerizing and Mogard intersperses his lengthy industrial trance spells with some unexpectedly tender and melancholy glimpses of light. Bittersweetly, Mogard has since left this revelatory phase behind to devote himself to more overtly beautiful and transcendent fare, yet every time I put this album on, I am sucked deeper and deeper into its complex evocation of mercilessly inhuman machinery poignantly mingled with soul and bleak radiance. To some degree, I wish I had covered Works back when it came out, but I suspect it needed some time to grow on me before I could fully appreciate it for what it is: one of the true masterpieces of the last decade.

According to legend, this enigmatic Serbian composer became deeply interested in music as a means of trying to recapture the sounds of the metal factory that he had worked at in Belgrade. If this 2016 collection of his early cassette releases succeeded in that aesthetic objective, that factory must have quite a terrifying edifice, as the best pieces evoke a relentless and pummeling mechanized horror akin to Fritz Lang's Metropolis. More importantly, some of these songs are absolutely mesmerizing and Mogard intersperses his lengthy industrial trance spells with some unexpectedly tender and melancholy glimpses of light. Bittersweetly, Mogard has since left this revelatory phase behind to devote himself to more overtly beautiful and transcendent fare, yet every time I put this album on, I am sucked deeper and deeper into its complex evocation of mercilessly inhuman machinery poignantly mingled with soul and bleak radiance. To some degree, I wish I had covered Works back when it came out, but I suspect it needed some time to grow on me before I could fully appreciate it for what it is: one of the true masterpieces of the last decade.

Abul Mogard's self-titled debut initially appeared as a self-released CDr back in 2012 before being more formally reissued later that year as a cassette on Zombi's VCO Records.Looking back, it is remarkable how fully formed, varied, and powerful his vision was even from that modest first step, as the relentlessly churning and seething "Drooping Off" remains one of the most stunning and heavy pieces in the Mogard oeuvre.The sizzling and corroded beauty of "The Purpose of Peace" is yet another essential piece, while the murky, forlorn psychedelia of Works' opening "Despite Faith" is not all that far behind.Notably, however, there are a few songs from that release that did not make it Works.The same is true of 2013's Drifted Heaven: only three songs from each release appear here.As a result, Works is not exactly a comprehensive retrospective of Mogard’s earliest work, so much as an idealized history–there is almost no need to delve into the full cassettes because all of the strongest pieces are collected here and the less dazzling fare was culled with fairly unerring judgment.There is one notable exception, however, as the epic "Android Manouvres" did not make the cut, presumably due to its somewhat extreme length.

The three pieces from Drifted Vision wisely do not depart much from the bold aesthetic vision of Mogard’s debut, yet they do exhibit some significant advancement in his execution and compositional approach.My personal favorite is "Tumbling Relentless Heaps," a mercilessly propulsive mechanized march of fried electronics, fluttering psychedelic flourishes, and brooding menace.The other two pieces from Drifted showcase Mogard's more meditative side, however."Post Crisis Remembrance" initially takes shape as a blurrily elegiac ambient reverie, but gradually darkens in tone as a rumbling undercurrent slowly swells and increasingly gnarled and distressed tones bubble up from its depths.Elsewhere, the slow-burning and achingly beautiful "Airless Linger" sounds like a lovelorn android from the future trying to replicate a great Tim Hecker album.

The final three pieces are taken from Mogard's 2015 The Sky Had Vanished cassette, which appears in its entirety here.It is a bit more varied than the previous releases, acting as something of a bridge between Mogard’s darkly mantric factory-inspired beginnings and the more radiant, melodic fare to come."The Sky Had Vanished," for example, is a prime example of the former, steadily building in roiling intensity to a heavily pulsing thrum spewing forth metallic harmonics.The following "Desires Are Reminiscences By Now," however, takes quite a different tone altogether.It is quite a quietly lovely and meditative piece, but its warmly languorous chord progression eschews all of the industrial throb and heft of the earlier work.Some corroded textures remain, thankfully, but the piece still feels like a curious anomaly–like a cloudy and regret-infused Eno pastiche.It is still quite good, of course–it just seems like a slightly awkward first step towards crafting more nakedly beautiful and unambiguously human fare (a direction he eventually perfected with 2017’s "All This Has Passed Forever").In any case, the true centerpiece of Sky is the 18-minute "Staring at the Sweeps of the Desert."Stylistically, it feels like the blurring together of the other two pieces, as a deep, throbbing bass pattern provides a sense of weary forward momentum beneath a bittersweet haze of smeared and blurry synth chords.It also marks a more ambitious compositional approach, as the original theme eventually dissolves to make way for bleakly shuddering coda.

I suppose it would be overreaching a bit to say that Works is a flawless collection, but the minor flaws are irrelevant in the face of how many truly stellar pieces are assembled in just one place.Each of the individual tapes is certainly excellent, but experiencing the distillation of several years of Mogard’s best work at once is like being hit by a goddamn meteor.Songs like "Drooping Off" and "Tumbling Relentless Heaps" struck me just as profoundly as any of the previous masterpieces that have knocked me sideways over the years (Soundtracks for the Blind, All The Pretty Horses, etc.), which is an experience that has become increasingly rare as I grow older and more jaded.It is nice to know that I still have the capacity for wonder and awe, even if I do not get to use it much.Rapturous praise of the content aside, I also love the scope of this collection, as it completely encapsulates a glorious and ephemeral window in Mogard’s evolution before he moved onto newer frontiers.I love that later work as well, but the era covered here remains Mogard's most distinctive and magical phase for me, as the "ghost in the machine" mingling of relentless industrial dread and human warmth is heavy, deep, and emotionally affecting all at once.Works is an absolutely canonical collection from an absolutely canonical artist.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I recently stumbled upon this bizarre debut during an especially deep Bandcamp plunge and it is deliciously unlike anything else that I have ever heard. Both the artist and the label are shrouded in a decent amount of mystery, but Heschl's Gyrus draws its inspiration from Cottern's fascination with "psychical auditory phenomena." Stylistically, she builds her harrowing auditory hallucinations from heavy, earthy drones akin to Richard Skelton's recent work, but builds them to crescendos that often feel like a swirling and feverish psychotic break from reality. Sometimes it can be beautiful, but the true genius of this album lies in the profoundly disturbing, alien, and intensely uncomfortable heights reached by pieces of "Akoasm II."

I recently stumbled upon this bizarre debut during an especially deep Bandcamp plunge and it is deliciously unlike anything else that I have ever heard. Both the artist and the label are shrouded in a decent amount of mystery, but Heschl's Gyrus draws its inspiration from Cottern's fascination with "psychical auditory phenomena." Stylistically, she builds her harrowing auditory hallucinations from heavy, earthy drones akin to Richard Skelton's recent work, but builds them to crescendos that often feel like a swirling and feverish psychotic break from reality. Sometimes it can be beautiful, but the true genius of this album lies in the profoundly disturbing, alien, and intensely uncomfortable heights reached by pieces of "Akoasm II."

Other Forms of Consecrated Life

No one will ever question Elizabeth Cottern's commitment to a theme, as this album not only borrows its name from the structure that houses the auditory cortex, but it consists of three numbered akoasms (a neurological term for auditory hallucinations).For its first few minutes, however, Heschl's Gyrus just feels like an atypically heavy, gnarled, and blackened drone album, slowly fading in as a hollow roar swarmed by submerged squalls of sputtering static.Gradually though, a slow-moving and elegiac melody begins drifting over the top and Cottern’s previously simmering battery of heavy textures overpowers the underlying drones.It is a compelling juxtaposition, as there is a lovely, dreamlike, and poignant "song" drifting through a haze, yet the roiling maelstrom beneath is the part that sneakily becomes the real focus.It unexpectedly calls to mind the oceanic shoegaze of Lovesliescrushing, as a glimpse of gorgeous, shimmering heaven seems to be fighting through a gale of roiling, sizzling cacophony.It is quite a stellar and epic piece, capturing Cottern at her most conventionally beautiful and comparatively accessible.The brilliant "Akoasm II" that follows, however, is clear evidence that accessibility is the least of her concerns.

Right from the start, "Akoasm II" is a disturbingly intense and challenging piece of music, as its simple structure of bleary drones is instantly disrupted by a nightmarish swirl of sickly, sliding synth tones.I am tempted to describe them as "shrill," but it would be more accurate to say that they have a visceral sharpness that creates an acute sense of deep discomfort.Unlike its predecessor, the underlying composition is not a significant part of the draw–there are some piano chords and a strange, rippling melody of harmonics, but those structured elements mostly just provide glimpses of an impossibly distant shore as I am enveloped by a lysergic sea of bubbling, swooping textures and ugly shifting harmonies.As someone who spends much of his time seeking out singularly strange and transcendent sounds, I can honestly say that Cottern's feverish miasma of strange gurgles and nightmarish glissandi is a deep mindfuck like no other.Whenever I hear it, I feel like I am trapped in a sensory deprivation tank and rapidly losing my grip on sanity, which is certainly an exquisite sensation.It is also an hopelessly impossible act to follow, so Cottern wisely heads in a somewhat different direction with the epic final piece.Clocking in at slightly over 30 minutes, "Akoasm III" is a bit more structured than its predecessors, unfolding as a sparse, repeating piano melody.Naturally, however, the real show is elsewhere, as a dense swirl of oscillating harmonies hovers above everything and steadily gathers power.Eventually, it becomes almost every bit as warped and absorbing as "Akoasm II," but it is a more nuanced and slow-buildingexperience, resembling a slow submersion into the otherworldly rather than being absolutely flattened by a nightmarishly psychedelic truck.

Obviously, I am quite curious about who Elizabeth Cottern might be, as Heschl’s Gyrus seems impossibly audacious, inventive, and sharply realized for an "unknown artist" with "no previous discography."Even if it is a pseudonym, I have no idea who would have both the musical ability and the depth of acoustic/neurological knowledge necessary to create something like this: Cottern takes drone music to a viscerally unnerving and otherworldly plane while simultaneously manipulating frequencies and overtones with the precision of a scalpel.It is a singular vision executed beautifully.In fact, this album genuinely feels like the culmination of someone's life's work rather than some secret side-project, so maybe Elizabeth Cottern is a real person after all.Whoever she is, I am damn glad she exists, as Gyrus completely blindsided me: this is an overwhelming, enveloping, and absolutely nerve-fraying delirium of an album.Instant classic.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Editions Mego's 250th release continues its ongoing legacy of cross-pollinating and perverting various threads of radical 20th Century music whilst concocting and propelling further ideas into the nebulous region where we currently reside.

With Ex Nihilo, Editions Mego resumes its enduring relationship with long-term collaborator and stalwart representative of the labels aesthetic with a new release from London’s most charming deviant occupant, Mr. Bruce Gilbert (formerly of Wire, Dome etc..).

Gilbert's peculiar approach to sound over four decades has seen him engage with a wide variety of practice and performance always hovering amongst the grey area between his mind and the surrounding architecture. Ex Nihilo is another significant entry into Gilbert’s outre sound-book.

Inhabiting a murky zone between interference and trauma, Ex Nihilo is a daring and dark audio ride through a contemporary ketamine haze, one which haunts identifiable parameters whilst remaining too oblique to be truly quantified. "Change and Not" teases discomfort, "Black Mirrors" embraces disorder, "Nomad" skirts the unsettling.

Whilst never quite resolving its own logic, Ex Nihilo invites the casual listener to join a devastating, peculiar, and somewhat paranoid fantasy (reality?).

Another effortless Gilbert classic.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

In recent years, Benjamin Finger has become quite a prolific and amusingly elusive artist to try to keep up with, releasing a steady stream of handmade limited editions or small vinyl runs on various European labels. He has also expanded his palette considerably from the gorgeous psych-collages of his debut (Woods of Broccoli), alternately exploring piano miniatures, off-kilter pop experiments, and an occasional stab at gleefully garbled dance music (and sometimes ingeniously blurring the lines that separate those various facets). My favorite side of Finger’s art remains his collage side, however, so I was delighted to find that For Those About To Love was a substantial plunge back down that particular rabbit hole. No one else does sound collage like Finger, as his unshakeable pop sensibility remains intact no matter how deconstructed and lysergic things get, resulting in a lovely snow-globe dream-world swirling with glimpses of warmth, tenderness, and sublime melody.

In recent years, Benjamin Finger has become quite a prolific and amusingly elusive artist to try to keep up with, releasing a steady stream of handmade limited editions or small vinyl runs on various European labels. He has also expanded his palette considerably from the gorgeous psych-collages of his debut (Woods of Broccoli), alternately exploring piano miniatures, off-kilter pop experiments, and an occasional stab at gleefully garbled dance music (and sometimes ingeniously blurring the lines that separate those various facets). My favorite side of Finger’s art remains his collage side, however, so I was delighted to find that For Those About To Love was a substantial plunge back down that particular rabbit hole. No one else does sound collage like Finger, as his unshakeable pop sensibility remains intact no matter how deconstructed and lysergic things get, resulting in a lovely snow-globe dream-world swirling with glimpses of warmth, tenderness, and sublime melody.

As alert readers may have deduced from the title, For Those About to Love is an album with a strong theme running throughout its nine pieces, as Finger gamely attempts to "journey into the mysteries of the heart."Such a sincere and ambitious endeavor is admittedly extremely treacherous territory in the realm of underground/experimental music, but it is also a fertile ground for inspiration and deep emotion that occasionally yields some truly great work (like Jefre Cantu-Ledesma's Love is a Stream, for example).Finger, to his credit, proves to be up to the task, as he deftly sidesteps the saccharine and the predictable in favor of sustained and delirious phantasmagoric plunge into a woozy and flicking haze of nervousness, worry, joy, pain, tenderness, and intimacy.In some of the better pieces, all of those threads seamlessly intertwine and blur together in a complexly textural and emotionally resonant cocktail.The opening "Lipstick Shades" is an especially fine example of Finger's deliciously disorienting and abstract necromancy, as a simple piano melody quickly gives way to a billowing psychedelic maelstrom of swooping, cooing female vocals; brooding drones; and a host of strange backwards scrapes, buried loops and snatches of melody.It feels like I put on an familiar record and it inexplicably began playing backwards to reveal a hypnotic and ghostly world of previously inaudible sounds, plunging me into an uneasy dream state.

While "Lipstick Shades" is certainly representative of the overall aesthetic that pervades Love, Finger’s deliciously blurred, shimmering, and psychedelic world is also a varied one, as he finds a way to imbue each of these surreal vignettes with its own character.The richest vein surfaces in the middle of the album, as Finger hits a three-song run of lushly immersive and dreamy nirvana.On the achingly beautiful "Ultraviolet Light," languorous female vocals from Inga-Lill Farstad and Lynn Fister seductively intertwine and blur together in a time-stretched and deconstructed soul jam beset by a chorus of chirping birds."Transparent Mind," on the other hand, weaves an obsessively repeating and complexly layered loop of gauzy cooing vocals that feels like modern classical minimalism mingled with submerged synth swoops that resemble a digitized jungle expedition.Elsewhere, "Eyeball Humidity" mingles together Satie-esque snatches of piano melody with a heady wash of shuddering drones, eerie feedback, childlike yowls, and disorienting field recordings.It is easily one of the more lysergic mindfucks on the album, as its amorphous structure seamlessly drifts from lovely chord swells to blooping and space-y synth motifs to squalls of gnarled vocals and echoing voices without ever lingering particularly long on any one motif.Obviously, I like some bits more than others and wish they stuck around longer, but the magic lies in how ephemeral and elusive all the individual pieces seem.It is like getting an unexpected glimpse of a wonderful memory, then quickly losing it again in the roiling entropy of the subconscious.Curiously, however, my favorite piece is the closing "Shrink Into Love," which dispenses almost entirely with layered psychedelia in favor of just a stuttering and beautiful chord progression unfolding beneath a haze of angelic vocal drift, albeit one punctuated with some unexpectedly sharp and warbly textures.It might be simplest piece on the album, but it can afford to be, as it is built upon the strongest motif.

Some of the other songs do not quite work as well or feel more like vaporous interludes than substantial pieces, but how often Finger decisively hits the mark is somewhat irrelevant, as the degree to which he succeeds overall is far more intriguing.With For Those About to Love, Finger attempts to say the ineffable, quixotically setting out to capture the impossible complexity and nuance of being in love and sometimes unexpectedly succeeding.To a larger degree, however, this album is even better at evoking the elusive, fragile, and unpredictable nature of memory, unfolding as an alternately lovely and painful flow of decontextualized, recontextualized, and indistinct glimpses of poignant moments or intimations of intense feelings.As such, this is probably Finger's most ambitious and thematically absorbing album from an artistic standpoint.It also one of his best albums in general, achieving the sustained depth, immersiveness, and rich attention to detail that is essential for a great headphone album.More importantly, this album captures what is unique about Benjamin Finger's art extremely well, as he approaches sound collage with a guileless humanity and depth of feeling rarely seen in the experimental music milieu, crafting complex and cerebral soundscapes that are soulfully direct rather than obscured by ambiguous artifice.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

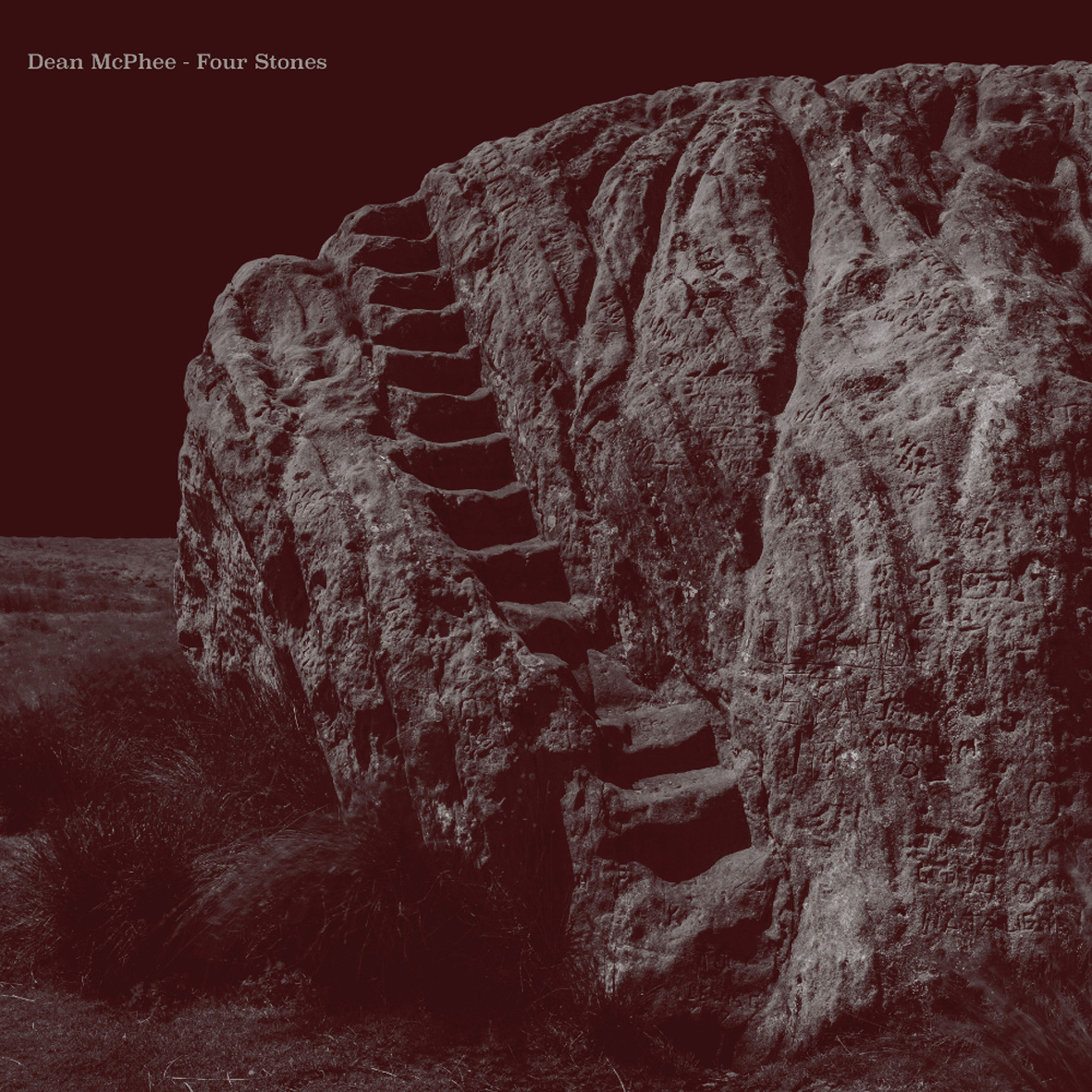

Over the course of the last decade, Dean McPhee has quietly and unhurriedly established himself as one of most compelling and unique solo guitar artists around, weaving gorgeously meditative reveries with a masterful use of ghostly delay effects. This latest album, his first since 2015, compiles remastered versions of three pieces that have surfaced on several elusive Folklore Tapes collections, as well as a pair of new pieces. All are characteristically fine, but both "The Devil’s Knell" and the epic "Four Stones" rank among the most mesmerizingly sublime work that McPhee has yet recorded, making this his most essential album to date.

Over the course of the last decade, Dean McPhee has quietly and unhurriedly established himself as one of most compelling and unique solo guitar artists around, weaving gorgeously meditative reveries with a masterful use of ghostly delay effects. This latest album, his first since 2015, compiles remastered versions of three pieces that have surfaced on several elusive Folklore Tapes collections, as well as a pair of new pieces. All are characteristically fine, but both "The Devil’s Knell" and the epic "Four Stones" rank among the most mesmerizingly sublime work that McPhee has yet recorded, making this his most essential album to date.

Hood Faire

The opening "The Blood of St. John" dates back to Folklore Tapes' 2016 homage to midsummer traditions, Crown of Light.In many ways, it is a quintessential Dean McPhee piece, as it feels like a kind of transcendent, slow-motion blues that unfolds over a bleary haze of shimmering delay.Even that description is exasperatingly reductionist though, as McPhee's crystalline cascades of serpentine melodies seamlessly pull in shades of more exotic influences from Mali and Morocco to reach towards something far more ecstatic than a mere guitar solo.The following "Devil’s Knell" also originates from one of Folklore Tapes' seasonal collections (Midwinter Rites and Revelries), but takes a more languorous and drone-influenced approach, capturing McPhee's work at its most achingly gorgeous.It initially takes shape as a lovely, glimmering fog of shivering chord swells before unexpectedly blossoming into a tumbling descending melody evanescently trailed by a ghostly afterimage.That tactic has sparingly surfaced before on other Dean McPhee records and it remains his most dazzling trick, as the overlapping and out-of-phase doppelganger melody is beautifully disorienting and creates a wonderfully dreamlike wake of hanging overtones.The album's first side draws to a close with yet another Folklore contribution, "Rule of Threes," borrowed from their 2012 collection devoted to the Pendle Witch Trials of 1612.While it is unmistakably a Dean McPhee song due to its chiming clarity and dreamily time-stretched pacing, it also clearly harkens back to an earlier phase in his evolution, as it is much more structured and conventionally melodic than his recent work.It is neither better nor worse for that, yet it feels more like a fantasia on an existing piece of traditional music than something that is spontaneously and intuitively conjured into being.

That said, the newer "Danse Macabre" is also quite structured, as it is built from an obsessively looping and rippling minor key arpeggio.I doubt anyone could ever mistake it for an appropriated piece of traditional music, however, as that one chord endlessly loops in hypnotic stasis and gives the piece a strangely lagging and off-kilter pulse that creates a disorienting sense of unreality.Over the top of that unusual backdrop, however, McPhee unfurls a sleepily lovely and melancholy glissando-heavy melody.The odd, frozen-in-time looping structure of "Danse Macabre" makes it feel more like an interlude than one of the album's more substantial pieces, but it is certainly a beguiling one.McPhee saves his best and most ambitious work for last though, as the title piece is a slow-burning and gently pulsing epic that transforms from one gently simmering motif to another as it builds towards its climactic final theme.Notably, "Four Stones" makes prominent use of a new element in McPhee’s palette: a bass drum.It is used so subtly that it is easy to forget that it is even there, but it sneakily gives the piece a somewhat more muscular pulse than he would have gotten solely from looping bass notes.Overall, it is quite an impressive work both compositionally and performance-wise, given that everything is performed live with no overdubbing: McPhee nimbly alternates between different textures (clean melodies, feedback-swathed sustained tones, and ringing harmonics) while simultaneously maintaining a strong central thread, sneaking in occasional chord changes, and keeping a steady kick drum pulse with one of his feet.It is quite a juggling act.Nevertheless, all of that is merely the pleasantly absorbing prelude to the quietly dazzling final movement, as a glacially descending cascade of harmonized tones coheres into a spectral and eerily beautiful dance.

That last bit nicely illustrates why I have been enraptured by Dean McPhee's work for so long (and also why he fits so seamlessly into the Folklore Tapes milieu): at any given time, there are always a handful of visionary guitarists who carve out their own compelling and distinctive niche, as well as many more who exhibit virtuosic technique or write consistently great songs.McPhee’s work checks off all three of those boxes, but his greatest moments reach another plane altogether where it feels like he is channeling something much deeper, more timeless, and almost supernatural.It is amusing to imagine some kind of ancient sorcery emerging from such modern gear as a Telecaster and some echo and delay pedals, but it is also easy to imagine McPhee being tried as a witch if he had gotten these sounds out of a stringed instrument in Pendle circa 1612–there is a layer beyond mere melody and harmony here that feels like time itself is blurring and the veil of reality has partially dissolved to offer a glimpse of something more mysterious.Needless to say, that sublime feat of illusion appeals to me immensely.This album is wonderful.

Read More