- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Dais Records is proud to unveil the new dark pop masterpiece from artist and composer Tor Lundvall. His first vocal album since 2009’s Sleeping and Hiding, and following the release of two instrumental albums and three CD box sets since that time, Tor returns with an album of beautifully intricate sadness and reflection: A Dark Place.

Born in 1968 in Wyckoff, NJ, Tor Lundvall is a painter and ambient composer. The son of Blue Note Records legend Bruce Lundvall, Tor was exposed to artwork, music, and creativity from a young age, and began his professional painting and music output in the late '80s.

Widely known for his dark imagery and thoughtful, provocative soundscapes, Tor Lundvall’s artwork is all-encompassing. His music, when paired with his paintings, creates a world within which one could easily disappear.

An intensely private individual, Tor Lundvall eschews the gallery circuit and live performances for his private studio in Eastern Long Island, NY, preferring to show his artwork privately and focus on studio production and writing without the pressures of the audience and all it encompasses.

Dais Records is honored to provide another glimpse into his world through his recordings. We hope you find it as special and as unforgettable as we do.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Air Lows is the debut solo album by Silvia Kastel.

The Italian artist has been a fixture of the underground since her precocious teens, clocking up many miles in Control Unit with Ninni Morgia ("It’s like Catherine Deneuve dumped two cases of post-Repulsion psychiatric notes over Pere Ubu’s Dub Housing, lit the fuse and, ahem, stood well back" – Julian Cope), including collaborations with the likes of Smegma, Factrix, Gary Smith, Aki Onda and Gate (Michael Morley of The Dead C). Through her own label, Ultramarine, she has released music by the likes of Raymond Dijkstra, Blood Stereo and Bene Gesserit.

Both solo and in her work with others, Kastel has explored the outer limits and inner workings of no wave, industrial, dub, extreme electronics, free rock and improvisation. Air Lows – which follows the cassette releases Love Tape (2011), Voice Studies 20 (2015) and The Gap (2016) – is both her fullest and most refined offering to date, a work of vivid, isolationist electronics which draws deeply on her past experience but assuredly breaks new ground.

Prompted by a late-flowering interest in techno and club music, Kastel sought to create something which combines a steady rhythmic pulse with the otherworldly sonorities of musique concrete, and avant-garde synth sounds inspired by Japanese minimalism and techno-pop (Haruomi Hosono’s Philharmony being a particular favourite). The formal artifice of muzak / elevator music, the intros and outros of generic popular songs, the extreme light-heavy contrasts of jungle, the creative sampling of hardcore, and the very "human" synths in the jazz of Herbie Hancock’s Sextant and Sun Ra: all these things were touchstones for Air Lows' conception and composition. All strains of music addressing – and complicating – the relationship between the human and the technological. By extension, visual inspirations also proved important: anime, and the avant-garde fashion of Rei Kawakubo. What does that shirt or dress sound like?

Though used sparingly, Kastel’s voice remains her key instrument, whether subject to dissociative digital manipulations as on "Bruell," delivering matter-of-fact spoken monologues, or providing splashes of pure tonal colour. Recorded between her expansive Italian studio and a more compact, ersatz set-up in Berlin, Air Lows gradually takes on some of the character of the German capital: you can hear the wide streets and empty spaces, the seepage of never-ending nightlife, the loneliness. Air Lows is The Wizard of Oz in reverse: the glorious technicolour J-pop deconstructons of its first half leading inexorably to the icy noir of "Spiderwebs" and "Concrete Void." These later tracks are reminiscent of 2015’s magnificent 39 12", Kastel in the role of numbed, nihilistic chanteuse stalking dank, murky tunnels of reverb and sub-bass. But there is contradiction and emotional ambiguity to Air Lows from the outset, and throughout: a sense of both infinite space and acute claustrophobia; energy and inertia; fluency and restraint.

Out now on Blackest Ever Black.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Written during what Dimitris Papadatos, aka Jay Glass Dubs, describes as "an adventurous and bold period," and holding material issued on tape by various labels between 2015-2016, the Dubs compilation frames a singular, stripped-down take on classic dub forms, wherein Jay Glass Dubs perceptibly retains the sound’s heavy function and mystic qualities, but subtly updates its palette with a range of nods to a myriad of unexpected, angular styles.

The results form a sort of ghostly, filleted subtraction of classic dub architecture, all plasmic tones and diaphanous, boneless structures buoyed by an often overwhelming, yet somehow intangible bass presence. Beyond the obvious, thematic ligature that connects the material, which was all recorded within a very short period of time, the artist also suggests there is an underlying, encrypted similarity to the material which is "merely apparent to me," and awaits much closer investigation from keen ears.

From Jay's eponymous 2015 debut for Hylé tapes, listeners will encounter the heaving smudge of Definition Dub, the serpentine, Coil-like digital delays of "Grumpy Dub," and a grime drone drill "Depression Dub." Off the II tape for THRHNDRDSVNTNN comes the darkwave synths and militant step of "Magazine Dub" recalling a gauzier Equiknoxx production, next to the bass-less scudder, "Detrimental Dub" and the shoegazing bloom of "Daria Dub," while his III tape tees up some abyssal highlights in the vertiginous "Hilton Dub," the melancholy, Basic Channel-scoped scale of "Sieben Dub," and the HTRK-esque starkness of "Everlasting Dub."

Exclusive to the set is "Perfumed Dub," recorded in 2017 and pointing to vast, layered, atmospheric directions for a timeless project which is only just hitting its stride.

Out now on Ecstatic.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

12k is very happy to announce a new LP from long-time label favorite and ever-elusive Shuttle358. With Field, Shuttle358’s Dan Abrams returns to the beautiful roots he layed down with his now-classic Frame (12k1011, 2000) which Alternative Press heralded as "Ranking alongside Aphex Twin's Selected Ambient Works II and Eno's Music for Airports in its evocation of imaginary space.", and which Boomkat (UK) called "Shuttle358's undisputed masterpiece." His distinct human imprint on the highly digital sounds of the microsound and clicks and cuts movement of the time played out across his other releases as well including Optimal LP (12k1005, 1999), Chessa (12k1030, 2004) and Understanding Wildlife (Mille Plateaux, 2002).

It is in this specific space and through splintered memories from the dawn of the 2000s that brings Shuttle358 back to his early explorations with Field. Specifically, those sounds nestled in computers from the late '90s running period software and "graced"by the lo-fi color of early DSP algorithms. Abrams deliberately takes advantage of slow CPU cycles and crashes on old computers to piece together a framework of disjointed rhythms and melodic loops that sound like they're crawling and skittering from a new digital dystopia. This landscape unveils elements that made his early work so powerful by the way he combines the broken with the beautiful. Deep rhythms made from truncated transients provide the foundation for ghostly vocal snippets and the signature musical ambience that defines the Shuttle358 atmosphere.

In a way, Field can be seen as a rebirth of the glitch, a modern take on the captivating microsound movement of the early 2000s and a powerful statement from Abrams who connects the dots and further deepens and expands his sonic story.

Out now on 12k.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

On first listen, Lou Rebecca's debut EP sounds like an unabashedly pop-centric record: all vintage synth leads, bass sequences and obvious digital drum machines. Closer listening reveals more layers, however, and while it is no doubt intended to be pop music, there is an additional, subversive depth to the sound that cannot usually be expected from music that so heavily hinges on memorable hooks and melodies.

On first listen, Lou Rebecca's debut EP sounds like an unabashedly pop-centric record: all vintage synth leads, bass sequences and obvious digital drum machines. Closer listening reveals more layers, however, and while it is no doubt intended to be pop music, there is an additional, subversive depth to the sound that cannot usually be expected from music that so heavily hinges on memorable hooks and melodies.

Part of this added depth may be the role that Parisian by way of Austin, Texas artist plays in her music.Rather than just singing (which she does exceptionally well in both English and her native French), she also plays most of the instruments, writes all of the songs, and even arranges her own video choreography.It is this hands-on attention to detail that can take the synthy, 1980s pop throwback "Tonight" into more complex realms of weird electronics and tinges of experimental sound lurking just beneath the uptempo veneer.

The lengthier "Neverending" also demonstrates more of Rebecca's diverse repertoire.With a piano lead, she blends in some excellent synth sounds and catchy drum programming, but as a whole the mix is kept open and sparse, letting all of the instruments, as well as her vocals, breathe and establish their own space.Switching vocals between French and English, the song builds to bigger, more complex and dramatic sequences leading to its conclusion.

Space is also utilized expertly on "Fantôme."Lead by a simple but memorable music box like melody, she delivers her beautiful vocals in French, with added electronic and synth accents to it, giving a great sense of depth from a stripped-down arrangement."If You Can" even features a bit of saxophone courtesy of Sarah Malika Boudissa, cementing its 1980s pop credibility but, again, careful production and nuanced arrangement give it a sense of subtlety that could otherwise be lost.

Given its shamelessly pop leanings, Lou Rebecca's debut may not appeal to the synth folks who like their songs dour and depressing, but there is much more here than meets the eye.Sure it is full of memorable choruses and catchy melodies, but its strength lies in its production and attention to detail.Even as someone who normally is not into music this light and upbeat, I found a lot to enjoy.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

As Die Stadt's brilliant reissue campaign nears its end (it looks like about two more remain in the 18 disc series), this double disc compilation covers the first and fourth collaborations Asmus Tietchens had with UK artist Terry Burrows, the first album from 1986 (Watching the Burning Bride) and its 1998 reworking (Burning the Watching Bride). The earlier album is perhaps the most fascinating, as it clearly captures both Tietchens' early synth-heavy rhythmic style (the Sky and Discos Esplendor Geometricos eras), and heralds the more abstract direction his work would soon take.

As Die Stadt's brilliant reissue campaign nears its end (it looks like about two more remain in the 18 disc series), this double disc compilation covers the first and fourth collaborations Asmus Tietchens had with UK artist Terry Burrows, the first album from 1986 (Watching the Burning Bride) and its 1998 reworking (Burning the Watching Bride). The earlier album is perhaps the most fascinating, as it clearly captures both Tietchens' early synth-heavy rhythmic style (the Sky and Discos Esplendor Geometricos eras), and heralds the more abstract direction his work would soon take.

Watching the Burning Bride is the first of four thematically linked works, with volume two being Tietchens’ Abfleischung (a previous release in this campaign) and the third Burrows' The Whispering Scale, all of which shared similar artwork and shared source material and instrumentation.The collaboration that produced this album is one rarely needed these days:postal mail.The two would record their own parts as source material, and then ship off to the other to rework.The contrast between the two artists is also a major facet:by this point Tietchens had been recording for around two decades and had built a rather technologically advanced studio with Okko Bekker, while Burrows was young and early in his career, producing most of his recordings on an 8 track in his bedroom.

The final product of these two very different working conditions is a seamless blend, however.Some of the songs clearly show the mark of Tietchens' early 1980s sense of rhythm:"Bride 2" (each piece was originally represented by an abstract symbol, here they are numbered) is a short bit that builds up to the industrial-ish sound he cultivated on his releases on Esplendor Geometrico's label before falling apart very quickly."Bride 10" also features this similar sense of rhythm, lurking more beneath a reverberated sci-fi soundtrack sound that heralds the more abstract works that Tietchens would later be involved in.

Some of these pieces also bring up directions that Tietchens and Burows could have gone in, but did not.On "Bride 4," heavily featured is Burrow’s then-new DX7 synth and, surprisingly enough, drums.The song comes together almost like a very strangely produced John Carpenter or Goblin soundtrack that is painfully too short, with the following piece running with these elements and putting them together in a more abstract, more disturbing framework."Bride 12" is similar in mood, but not in approach:a collage of rattling spring reverb and metallic clanking that somehow gels into a strangely melodic piece.

There are a few bizarre moments to be had on this album as well, and I mean that in the most positive of ways.For "Bride 7," Tietchens’ vintage drum machine and synths form the basis, with the addition of dubby bass guitar and actual vocals from Burrows, although limited to the span of only two minutes.Tietchens himself is responsible for the addition of some female vocals (a tapeloop of "some hippies singing" according to the liner notes) on "Bride 6," giving a bit of unlikely humanity within the distant clanking and distant, droning space.Two bonus songs are appended to this disc, "Torso 1" and "Torso 2."Apparently these are some of the untouched source materials used, and they are rather strange combinations of noisy orchestra hits and cheap MIDI drum programming.

Burning the Watching Bride appeared some twelve years later, with each artist taking one side of the album and reworking the material based on the newer technologies available to both artists.Burrows’ side, "Bride 23" (the numbering continues from disc one) takes the form of a single 23 minute composition that utilizes all of the elements from the album, with some tasteful processing and treatments.The final product is in some ways reminiscent of a "megamix," keeping some elements original while adding new sounding effects, but it comes together like a completely consistent composition.

Tietchens' half of this album is closer in structure to the original, being a sequence of five shorter, more diverse sounding works."Bride 18" is rather consistent with his later 1990s work:swirling electronics and hints of dark ambience, peppered with the occasional beep or reverberated noise, but otherwise solid and sustained.Both "Bride 20" and "Bride 21" keep these elements but Tietchens allows more of Burrows' original FM synth work to come to the forefront, at times buried under a nice filtered drone.The fourth especially showcases them, again taking on a more soundtrack-like feel that balances sound and space exquisitely.

I have always favored Asmus Tietchens' 1980s work that was not far removed from the world of industrial the most, so I cannot help but love Watching the Burning Bride most, although admittedly the short, vignette style of song was at times frustrating, since I felt they ended too quickly.In some ways Burning the Watching Bride ends up being a victim of its time, since those early Protools style experiments and processing lack the same level of innovation and humanity as the older, more primitive works have.It is still a very strong album though, even if I prefer its predecessor, and pairing the two together makes perfect sense.Not to minimize Terry Burrows' extensive role in these recordings, but the set makes for an excellent snapshot of what Tietchens had been doing in the past, and what he would continue doing in the future.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

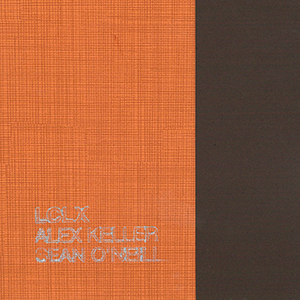

LCLX is a rather fast follow-up to this Texas duo’s other recent work, Kruos, but by no means does it seem rushed or hurried. Alex Keller and Sean O'Neill again have produced a work that is both familiar and alien, through careful use of field recordings and understated processing to capture the world around them, mixing the mundane with the uncommon to create environments that sound much more unique then they likely were in the first place.

LCLX is a rather fast follow-up to this Texas duo’s other recent work, Kruos, but by no means does it seem rushed or hurried. Alex Keller and Sean O'Neill again have produced a work that is both familiar and alien, through careful use of field recordings and understated processing to capture the world around them, mixing the mundane with the uncommon to create environments that sound much more unique then they likely were in the first place.

The lengthy title piece that opens LCLX is actually a reworking of material Keller and O'Neill utilized for their first performance together in 2015.The nearly 16 minute work is based solely on recordings captured at the Charles Alan Wright Intramural field in Austin, Texas, with little or no discernible processing or treatment to the sound.A heavy droning bass and complementary buzzing noise are immediately apparent from the start, apparently capturing the field’s bright lighting that is as sonically distracting as it apparently also is visually.

Alongside this somewhat abrasive sound is the recordings I would expect in this sort of location recording:passing vehicles, the occasionally disruptive motorcycle revving by, or car honking to add to the feeling of audio pollution.The same recordings also capture more pleasant moments, such as the chirping of birds and other wildlife.Somewhere in the middle of natural beauty and the sonic ugliness of industry lies the occasional snippet of conversation by passersby.

The remaining five pieces that make up this album come from less clear pedigrees, but all revolve around field recordings captured in urban and rural areas, and all manner in-between.Some of these are perversely enjoyable:I would hate to have to listen to the jackhammering captured on "Ununbium" against my will, but captured on record there is revealed an almost musical quality to it, emphasizing nuances to the sound I would have otherwise ignored.

In a more natural mood, "Ununpentium" is the classic sound of a rainstorm.The pitter-patter of raindrops both near and far from the recording device is a rather peaceful bit of wet, muggy sound.The added rumble of thunder that appears later on adds to that "enjoying nature" feel, but the passing airplane makes for an intentional distraction.The ten minute "Ununquadium" mirrors "LCLX" in its complexity, bringing in a series of sounds that are in this case not overly recognizable, but work well alongside one another.Distant rumbles and near static bursts act as the core, with the occasionally overt bit of bird chirping showing up.Later on a rhythmic clattering appears that could be studio treated with reverb and echo, or perhaps completely natural in their source.This ends up being mixed with a series of other unspecified mechanical sounds, resulting in a piece that lies in somewhere between the purity of nature and the sonic pollution of mankind.

Special note should be made of the CDs unconventional packaging.Folded within a piece of heavy paper and even heavier stamped fabric, it has that tactile, handmade quality to it that was so prevalent in the 1990s noise scene (such the G.R.O.S.S. label run by the late Akifumi Nakajima/Aube) that too many releases lack these days.Like Kruos, LCLX is another example of the intricacy and nuance possible from just using everyday field recordings.Alex Keller and Sean O'Neill are, at least superficially, just capturing the world around them as it happens, but the difference lies in their recording techniques and the final presentation.It is that use of the familiar and the unfamiliar that makes these works so engaging, and is an exemplary example of the art form.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

We're excited to welcome New York City-based composer and performer Lea Bertucci back to NNA for a brand new full-length LP, Metal Aether. Lea’s early 2017 cassette release All That Is Solid Melts Into Air focused on her role as a composer, with a hand-picked selection of talented musicians performing her minimal compositions. Metal Aether instead showcases her role as a performer, revealing four pieces that represent approximately 3 years of ideas and gestures for alto saxophone and magnetic tape.

Much like the recordings of her previous NNA release, Metal Aether continues to explore Lea’s acute interest in the nature of acoustics and the harmonic accumulation of sound, with its four pieces having been recorded in Le Havre, France in a former military base, and in New York City at ISSUE Project Room. With her horn, Lea produces pulsing minimalist patterns, transcendent drones, and upper register squalls that envelop these spaces in waves of overtones, microtones, and psychoacoustic effects. Tracks like "Accumulations" explore evocative, ancient-sounding melodic figures, while tracks like "Sustain and Dissolve" relish in the microtonal relationships between overlapping sustained notes. Aside from the saxophone, Bertucci further interacts with physical space by fortifying these pieces with manipulated field recordings from diverse locations, ranging from Mayan pyramids to NYC subways. Other instruments such as prepared piano and vibraphone can be heard on this album, processed through tape to unite melody and texture together as one. Lea displays a firm grasp of the inherent possibilities of sound manipulation to maximize her music’s power through the recording process itself, mixing conflicting fidelities to achieve a deeper, more organic form of expression.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Black Truffle present the premier recordings of two recent works by legendary American experimental composer Alvin Lucier.

Lucier has been crafting elegant explorations of the behavior of sound in physical space since the 1960s and is perhaps best known for his 1970 piece "I Am Sitting In a Room." He has written a remarkable catalog of instrumental works that focus on phenomena produced by the interference between closely tuned pitches, often using pure electronic tones produced by oscillators in combination with single instruments. Demonstrating the restless creative drive of an artist now in his 80s, the two recent works presented here both feature the electric guitar, an instrument Lucier has just recently begun to explore.

In "Criss-Cross," Lucier's first composition for electric guitars, two guitarists using e-bows sweep slowly up and down a single semitone, beginning at opposite ends of the pitch range. The piece exemplifies Lucier's desire not to "compose" in the conventional sense, but rather to eliminate everything that "distracts from the acoustical unfolding of the idea."

In this immaculately controlled performance of "Criss-Cross" by Oren Ambarchi and Stephen O’Malley, for whom the piece was written in 2013, a seemingly simple idea creates a rich array of sonic effects — not simply beating patterns, which gradually slow down as the two tones reach unison and accelerate as they move further apart, but also the remarkable phenomenon of sound waves spinning in elliptical patterns through space between the two guitar amps.

In the comparatively lush "Hanover," Lucier draws inspiration from the photograph on the cover, an image of the Dartmouth Jazz Band taken in 1918 featuring Lucier's father on violin. Using the instrumentation present in the photograph, Lucier creates an unearthly sound world of sliding tones from violin, alto and tenor saxophones, piano, vibraphone (bowed), and three electric guitars (which take the place of the banjos present in the photograph). Waves of slow glissandi create thick, complex beating patterns, gently punctuated by repeated single notes from the piano. The result is a piece that is simultaneously both unperturbably calm and constantly in motion.

Out now on Black Truffle.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This is the first album that I have encountered from Jo Zimmermann's long-running and amusingly titled Schlammpeitziger project (the unwieldy pseudonym is borrowed from a fish that apparently breathes through its anus). The general lack of Schlammpeitziger in my life before now is mostly because the bulk of his oeuvre has been released exclusively on German labels, aside from a retrospective of his early years released on Domino back in 2001. I am delighted that he has finally crossed my path though, as I am endlessly fascinated by outliers and iconoclasts and Zimmermann is a prime specimen. He is also a bit of an erratic pop genius, albeit a gleefully absurd and sometimes self-defeating one. At its best, Damenbartblick is a glimpse of what a slightly tipsy Kraftwerk might have sounded like if they were joined by Steven Stapleton in an extremely whimsical mood. Regrettably, Zimmermann only rarely reaches such heights, but they are wonderful while they last (and the remainder of the album is a pleasant enough batch of bubbly synth-pop instrumentals).

I was not sure what to expect from this album, so I was completely blindsided by the opening "Ekirlu Kong," a bombshell that captures Zimmermann at the absolute height of his powers.It begins with an almost cartoonishly gurgling bass line and a host of jabbering animal noises, but almost immediately coheres into a wonderfully burbling and hook-filled masterclass in idiosyncratic electronic pop.While Zimmermann makes it all seem effortless, the layered complexity is dazzling to behold, as he deftly juggles synths of several different (and delightful) textures while casually tossing off one great melodic hook after another.Also of note, "Ekirlu Kong" is one of the few songs where Zimmermann decided to "sing," which adds a whole new level of appeal, as his droll, deadpan monologue oozes equal parts snarky charisma and wrong-headed derangement.At its core, "Ekirlu Kong" is a charmingly bubbly and sweet love song, but that is not the complete picture, as it is wryly undercut by the perverse absurdity of lines like "your farts smell like the breath of a rainbow unicorn."On paper, that admittedly sounds somewhat infantile and needlessly scatological, but works beautifully in context, injecting some charming subversion into Zimmermann’s gorgeous pop confection.Lamentably, Damenbartblick never quite reaches that level ever again, though the later and considerably more hostile "Angerrestbay" happily comes somewhat close ("Hey stupid man–your brain is a dick").The rest of the lyrics are similarly provocative/ridiculous, of course, but the strangely rolling, dragging groove and funky clean guitars make for another fun and winning formula.

Consequently, I dearly wish Zimmermann sang more on the album, as his vocals are one of the magic ingredients that makes Damenbartblick something to get excited about: it is like an especially smart, funny, and precocious friend made a party album that deliberately mistranslated many lines into amusingly awkward and baffling pronouncements ("You got a perfect health care system–I got 18 seagulls flying in circles in my room").As entertaining as that impish piss-takery can be, it would probably get old quickly if Zimmermann were not also something of a synth wunderkind/studio wizard.The latter probably explains why so few of these songs feel like the fully formed synth-pop gems they could be, though Zimmermann is probably also reluctant to wear out the welcome of his limited vocal talents.Given that this is a one-man endeavor, it must take an enormous amount of time to tweak something like "Ekirlu Kong" to glistening perfection, so trying to conjure up an entire album in that vein would probably grind Schlammpeitziger's output to a standstill for a couple of years.No one wants that.I am also curious about who the expected audience for Schlammpeitziger might be, as it is entirely possible that Zimmermann is largely content just making skillful, upbeat Kraftwerk pastiches, but also likes to throw in a few curveballs every now and then to amuse himself.If that is the case, I guess I just love the curveballs.More objectively, however, the instrumental pieces that comprise the bulk of the album lack the character of the vocal ones: they are pleasantly likable rather than great.I do not have any particular aversion to instrumentals, but there is nothing to fill the charisma void left by the disappearance of Schlammpeitziger's human element (more animal noises would be a good start, incidentally).

Of course, I bet I would appreciate Zimmermann’s instrumentals much more if my vague expectations had not been completely blown to pieces by such a stellar opener.Consequently, it seems unfair to say that this is a flawed album, as any grumbling feels like the whining of a spoiled child.The best analogy that I can come up with for Damenbartblick is that it is like an enchanted vending machine that unexpectedly gave me a freshly prepared dish of great chicken tikka masala rather than, say, a candy bar.On one level, it would be disappointing if most of the time it reverted back to giving me the expected result, but the more significant bit is that something truly amazing happens every now and then.In fact, that is the perfect summation of Schlammpeitziger: something truly amazing happens every now and then, so I would be a fool not to wait around to see what happens next.I suppose that makes Zimmermann more of a "singles artist" rather than an "album artist," but he is at least a damn great one: Schlammpeitziger has my unwavering attention now.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Released back in early 2017, Frequency is the underheard debut full-length from the duo of Coil/Cyclobe alum Mike York and Mark Pilkington (from Strange Attractor Press). Given that singular and occult-tinged pedigree, it is no surprise that something novel and wonderful emerged from their union. I suppose Coil’s more hallucinatory and amorphous late-period work is a solid touchstone, but it is also a mere jumping-off point, as Teleplasmiste descend even deeper into lysergic drone territory. At its best, Frequency is like a psychoactive depth charge dropped straight into my unconscious, exploding into a disorienting and almost vertigo-inducing swirl of colors and texture. While some of these swirling, smearing, and buzzing synth invocations admittedly strike deeper than others, the album as a whole is a tour de force of hypnotic, slow-burning, and reality-dissolving wave- and frequency-manipulation.

Released back in early 2017, Frequency is the underheard debut full-length from the duo of Coil/Cyclobe alum Mike York and Mark Pilkington (from Strange Attractor Press). Given that singular and occult-tinged pedigree, it is no surprise that something novel and wonderful emerged from their union. I suppose Coil’s more hallucinatory and amorphous late-period work is a solid touchstone, but it is also a mere jumping-off point, as Teleplasmiste descend even deeper into lysergic drone territory. At its best, Frequency is like a psychoactive depth charge dropped straight into my unconscious, exploding into a disorienting and almost vertigo-inducing swirl of colors and texture. While some of these swirling, smearing, and buzzing synth invocations admittedly strike deeper than others, the album as a whole is a tour de force of hypnotic, slow-burning, and reality-dissolving wave- and frequency-manipulation.

In many respects, the opening "A Gift of Unknown Things" is the perfect and representative harbinger of the droning psychedelia to come, as it is built from densely buzzing and sustained synth tones that slowly swoop, swell, and oscillate in a sustained reverie.Gradually, a strangely hollow and plinking percussion motif appears, but the piece does not feel like an evolving composition so much as it feels like I was dropped in the middle of a strange and disconcerting sound world that eventually grows more complex texturally.It is not quite a brilliant enough illusion to fully transcend its likely improvisatory origins, but it is still an appealingly immersive and phantasmagoric place to linger.Later, "Mind at Large" returns to roughly the same territory, though it casts a deeper spell, as the central motif is embellished by a wonderfully queasy and gently fluttering periphery of blurred tones and buried subterranean plunges.That "densely buzzing and slowly swooping drones" template is reprised once more in the epic "Radioclast," albeit this time with an undulating undercurrent of feedback/harmonic-like ripples. I like all three pieces, but they are all very much cut from the same cloth and do not do much to establish Teleplasmiste as a unique and formidable entity.Given the intriguing body of work that both artists have behind them, I was hoping that Frequency would be more than just an atypically strong synth album that draws upon some especially cool influences.The pieces mentioned above admittedly are a bit more than that, as they creep into deep trance/altered state territory, but they are not quite the visionary break from the current synth milieu that was expecting.

Thankfully, that visionary break comes elsewhere on the album, as "Gravity is the Enemy" succeeds admirably in realizing the duo's stated objective of "blurring vintage synthesis and contemporary electronics with acoustic pipes to create a transcendent reverie that exists on a wavelength beyond both retro fetishism and modern-day machinations."At its foundation, it shares a densely throbbing bed of synth drones with everything else on the album, yet that is merely the framework, as York unleashes a sinisterly dissonant maelstrom of gnarled pipes over it to harrowing effect.There is also an added textural layer of odd crashes and hollow drips that imbues the piece with an otherworldly sense of place.I feel like I am about to be a human sacrifice for some kind of malevolent ancient ritual in Teleplasmiste’s time-traveling trance cave, which is definitely not a sensation I can get elsewhere.That is unquestionably the album's zenith as far as establishing a mesmerizing new niche is concerned, yet the following "Astodaan" is no less stunning.This time, however, the achievement is more of a compositional one, as the swirling haze of shimmering heaven in the periphery creates the feeling of an evolving chord progression quite different from the usual floating stasis.That is not the only innovation, however, as the central drones take on a far more visceral and snarling character and it is absolutely glorious.It also nicely illustrates the difference between a good Teleplasmiste song and a great one: one sneaks its tendrils into my consciousness and pulls me towards some kind of blurry and alien dream state and the other does that AND hits me on primal, seismic level.

The album is curiously rounded out by "Fall of the Yak Man," a haunting earlier piece that diverges significantly from the rest of the album in a couple of key ways (it has a melody and it lacks a heavy drone backbone). It has an ageless and elemental menace to it that I rather enjoy, but I think York and Pilkington’s intuitive move away from such composed-sounding fare was ultimately a good decision: Teleplasmiste are at their best when they erase all trace of themselves and just set about trying to dissolve mundane reality.Some pieces admittedly succeed more than others, but that is to be expected: York and Pilkington are like two necromancers trying to find the runes that will summon exactly the demon that they want–sometimes they do not get the ideal result, but that is because they are trying to do something that no one else can do in largely uncharted territory.That said, this is still a fine and absorbing album by any standard.Still, I am hoping that this is just a formative first step and that York and Pilkington will keep traveling this arcane path, as "Gravity" and "Astodaan" lay the groundwork for a second phase that could (and should) put Teleplasmiste on the same level as York’s iconic previous projects.

Read More