- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest release from the long-running ambient dub solo project of erstwhile Mi Ami/Black Eyes bassist Jacob Long is stirring up some feelings of regret about how I managed to sleep on this project for so long. While I am not yet sure if Ghost Poems simply caught me at the right time or if Long has been unusually inspired recently, my previous exposures to Earthen Sea left me feeling like the ambient/dub balance was too heavily weighted towards the "ambient" side to leave a deep impression. I suspect the balance has not changed all that much since I last checked in, but Long seems to have made a big leap forward in perfecting his execution with this album (it "further refines his fragile, fractured palette into fluttering arrythmias of dust, percussion, and yearning," according to the label). Apparently, I am very much into fluttering arrhythmias of yearning now, as the first half of this album boasts a handful of pieces that can stand with just about anything in Kranky's rich and influential discography: rather than resembling dub techno that has been deconstructed and dissolved into a soft-focus haze, Ghost Poems often feels like Long has managed to seamlessly combine the best of ambient and the best of dub techno into something fresh, wonderful, and uniquely his own.

This latest release from the long-running ambient dub solo project of erstwhile Mi Ami/Black Eyes bassist Jacob Long is stirring up some feelings of regret about how I managed to sleep on this project for so long. While I am not yet sure if Ghost Poems simply caught me at the right time or if Long has been unusually inspired recently, my previous exposures to Earthen Sea left me feeling like the ambient/dub balance was too heavily weighted towards the "ambient" side to leave a deep impression. I suspect the balance has not changed all that much since I last checked in, but Long seems to have made a big leap forward in perfecting his execution with this album (it "further refines his fragile, fractured palette into fluttering arrythmias of dust, percussion, and yearning," according to the label). Apparently, I am very much into fluttering arrhythmias of yearning now, as the first half of this album boasts a handful of pieces that can stand with just about anything in Kranky's rich and influential discography: rather than resembling dub techno that has been deconstructed and dissolved into a soft-focus haze, Ghost Poems often feels like Long has managed to seamlessly combine the best of ambient and the best of dub techno into something fresh, wonderful, and uniquely his own.

According to Long, one of this project's central themes is "the melancholy of 7th chords on a fake Rhodes patch," which feels like quite an apt and self-aware description. In lesser hands, that might be uncharitably viewed as a formulaic approach, but Long seems to instead belong to a more rarified type of artist who is passionately devoted to perfecting a single theme that obsesses him and he seemingly has no trouble finding myriad intriguing ways to keep that theme evolving. Unsurprisingly, blearily melancholy and repeating fake Rhodes chords are indeed the heart of the album, but Long inventively enhances that simple theme with a host of delightful textural and rhythmic elements. Some of those elements are expected ones, such as the presence of deep bass throb, understated kick drum patterns, and subtle cymbal flourishes that give these pieces their physicality and sense of forward motion. Those more conventionally musical touches are just pieces of a larger puzzle though, as Long also gets a lot of mileage from "domestic sounds (sink splashing, room tone, clinking objects) filtered through live FX to imbue them with an intuitive, immaterial feel."

In theory, that is not exactly new territory, but it sure feels like it sometimes (particularly on the opening "Shiny Nowhere," as crackling, shuffling, and dripping sounds gamely replace the expected snare and cymbals in the lurching, slow-motion groove). Given how explosive and cacophonous some of Long's previous bands have been, I was quite surprised by his talent for distilling a piece to its absolute essence and never playing a single wasted or unnecessary note. My favorite piece is the hiss-soaked and sensuously seductive "Stolen Time," but "Felt Absence" and "Snowy Water" help make the whole first half a murderers' row of elegantly frayed and dreamlike hits. To some degree, Long's "variations on a theme" aesthetic unavoidably starts to yield diminishing returns as I get deeper into the album, but some of his best ideas do not surface until later pieces like "Slate Horizon" and "Deep Sky" (both of which make very inspired use of subtly shivering cymbals and clicking drum sticks).

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

Similar to his recent works Family Secret and House Blessing, the newest work from drummer/percussionist Jon Mueller features little in the way of overt rhythms or obvious instrumentation. Instead, The Future is Unlimited, Always captures Mueller at his most spacious: layers of frequencies and tones that are as engaging as they are mysterious, and capturing more than just audio, but a deeper sense of existence.

Similar to his recent works Family Secret and House Blessing, the newest work from drummer/percussionist Jon Mueller features little in the way of overt rhythms or obvious instrumentation. Instead, The Future is Unlimited, Always captures Mueller at his most spacious: layers of frequencies and tones that are as engaging as they are mysterious, and capturing more than just audio, but a deeper sense of existence.

Consisting of a single 33-minute piece, The Future is Unlimited, Always features Mueller working with sustained tones, ghostly frequencies, and shimmering, low-end rumbles. The abstraction of sound takes on an almost spiritual quality that is palpable through the tones and textures that never fade into the background, but also never become too aggressive or oppressive. Instead they sit just at the right level to be mesmerizing while still allowing breathing room.

The instrumentation Mueller utilizes throughout this album is not the most apparent, but I think detect what might be some of his traditional percussion work weaved in, but processed and rendered into lush tones that float, rather than pummel. Beyond that, only what sounds like some digital treatments are identifiable, with everything else merging into a beautiful, dynamic world of various frequencies. Towards the end, a rumbling drifts in that also may be the sound of drums, but heavily treated into something else entirely.

Accompanied by a short piece of fiction in a luxurious digibook, Mueller clearly examines the existential and metaphysical realms with The Future is Unlimited, Always, and it continues to demonstrate what a multifaceted artist he is. His recent works have been exceptionally diverse, but these themes have been a consistent thread through them, and it is quite obvious throughout here as well. Sonically this could not be any more different than another favorite of mine, the relentless but meditative drumming of 2017’s dHrAaNwDn, but both feature his unique gift in conjuring a sense of space and place simply through sound.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

In general, releasing a three-hour album is a highly dubious endeavor, as such an extreme length usually turns even very good music into an endurance test and virtually guarantees that few people will ever listen to the entire opus more than once. When "Memphis dronegaze cult" Nonconnah do it, however, it feels like an absolute godsend. Part of that is because the husband/wife duo of Zachary and Denny Wilkerson Corsa lead what is possibly the most consistently fascinating and wonderful shoegaze/drone project around, but there is an equally important second part as well: the Corsas seem to be constantly collaborating with a host of talented guests. Unsurprisingly, that generates an ungodly amount of material and each major new Nonconnah album feels like a mere tantalizing glimpse into the innumerable killer jams and recording sessions that led up to the release. When I say that Don't Go Down to Lonesome Holler could have probably been an equally brilliant six- or nine-hour album, it is not hyperbole: there are over 50 credited performers involved in this album including folks from heavy hitters like Archers of Loaf, Swans, and No Age (as well as more than 60 instruments ranging from singing saws to cats). My guess is that the only limiting factor was how much time the Corsas could spend culling and editing their mountain of killer material without starting to lose their goddamn minds. This album is an absolute revelation ("Nonconnah's most comprehensive vision yet for the American halfpocalypse," according to the label).

In general, releasing a three-hour album is a highly dubious endeavor, as such an extreme length usually turns even very good music into an endurance test and virtually guarantees that few people will ever listen to the entire opus more than once. When "Memphis dronegaze cult" Nonconnah do it, however, it feels like an absolute godsend. Part of that is because the husband/wife duo of Zachary and Denny Wilkerson Corsa lead what is possibly the most consistently fascinating and wonderful shoegaze/drone project around, but there is an equally important second part as well: the Corsas seem to be constantly collaborating with a host of talented guests. Unsurprisingly, that generates an ungodly amount of material and each major new Nonconnah album feels like a mere tantalizing glimpse into the innumerable killer jams and recording sessions that led up to the release. When I say that Don't Go Down to Lonesome Holler could have probably been an equally brilliant six- or nine-hour album, it is not hyperbole: there are over 50 credited performers involved in this album including folks from heavy hitters like Archers of Loaf, Swans, and No Age (as well as more than 60 instruments ranging from singing saws to cats). My guess is that the only limiting factor was how much time the Corsas could spend culling and editing their mountain of killer material without starting to lose their goddamn minds. This album is an absolute revelation ("Nonconnah's most comprehensive vision yet for the American halfpocalypse," according to the label).

Given Nonconnah's unusual compositional techniques (an endlessly shapeshifting series of themes that blur and bleed into each other), the extended song durations (nothing clocks in under 20 minutes), and the fact that this album is the culmination of six years of recordings made in many locations (silos, graveyards, overpasses, etc.) involving several dozen participants, any attempt to concisely describe a single piece is absolutely hopeless. The overall effect, however, feels somewhat akin to being adrift on a sea of shoegaze-y guitar noise in a boat with no oars so I am completely at the mercy of wherever the waves decide to take me. Sometimes the guitar sounds are sun-dappled and beautiful, sometimes they are quivering and hallucinatory, and other times they are roaring and gnarled. Other times, however, the shimmering shoegaze tides roll back out to sea and leave me somewhere else enchanted and dreamlike. Occasionally, I catch myself wishing that a particular theme stuck around longer or had been expanded into a stand-alone piece, but those thoughts tend to immediately dissipate when said passage bleeds into something else that is every bit as gorgeous.

Aside from Zachary/Magpie's invariably beautiful and inventively warped guitar playing, there are extended nods to tape music, classic midwestern emo, numbers stations, spaced-out psychedelia, spoken word and everything in between (including a fireworks display) and it all fits together perfectly into an immersive and truly mind-expanding tour de force. But it is also more than that as well, as the spoken word/sample-based passages give the whole an oft-fascinating narrative arc that feels like an impressionistic swirl of the jumbled thoughts of a crumbling, confused, and possibly doomed empire: thoughtful monologues about capitalism and the nature of consciousness collide with institutional instructions on eluding active shooters and an impassioned preacher ranting about the end times. If these truly are the end times, at least we got an absolutely stunning album out of it as a consolation prize. I realize it is only July right now, but I feel quite confident in declaring this to be my favorite album of the year, as trying to imagine anything more ambitious, zeitgeist-capturing, and visionary album being released between now and December makes my synapses fizzle and smoke.

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

Following a multitude of self-released tapes and digital releases, Vagrancies is Austin, Texas's Andrew Anderson's first CD based work. Ostensibly created by the instrumentation and sources listed in the disc's liner notes, Anderson's treatment renders them largely unidentifiable, instead using them to construct something else entirely. Consisting of four long-form pieces connected with shorter interludes, Vagrancies covers a lot of ground, with an impressive amount of variety from piece to piece, but still a strong sense of continuity from one piece to the next.

Following a multitude of self-released tapes and digital releases, Vagrancies is Austin, Texas's Andrew Anderson's first CD based work. Ostensibly created by the instrumentation and sources listed in the disc's liner notes, Anderson's treatment renders them largely unidentifiable, instead using them to construct something else entirely. Consisting of four long-form pieces connected with shorter interludes, Vagrancies covers a lot of ground, with an impressive amount of variety from piece to piece, but still a strong sense of continuity from one piece to the next.

Anderson sets the tone for the disc with the opening "Dressed in No Light." It's a massive, tumbling avalanche of reverberated clicks, with a foghorn-like sound giving a ghostly approximation of a melody. The entirety is bleak and dour, with a fascinating density peppered with spinning and sputtering passages of sound. "Shadows Are Roots" differs in what almost sounds like an indistinct twang of an instrument expanding through a bassy hum. The metallic twang stands out and cuts through, but not in a jarring manner. With Anderson throwing in some percussive knocks, scrapes, and a few wet thuds, there is a lot going on, but never does it come across as unfocused.

Andrew Anderson then adopts a more musical focus with the other two lengthy pieces, using looping structures and a more overt sense of composition. On "Vagrancies," featuring Thor Harris—a previous collaborator, there are some almost conventionally musical passages buried under chaotic layers of birds and other fluttering noises. Anderson keeps the piece active, blending these different segments to excellent effect. A sequence of white noise bursts and digital detritus towards the end build to a wonderfully intense climax. Animal field recordings also feature heavily on "Melting Time." Here, birds and/or small animal chirps exist under an aquatic rumble, with ancient wind chimes over loose, warbling tape noise. There is a little less in the way of variety compared to "Vagrancies," however it is engaging from beginning to end.

The interstitial bits that connect the longer pieces come across as less composed, but instead fascinating collages in their own right, mixing unsettling field recordings, sputtering radios, answering machine messages, and heavy processing throughout. Vagrancies balances that subtle sense of menace that is inherent in works focused on reworking everyday sounds into completely abnormal contexts, but with just the right amount of conventional structures to ground it. Beautifully ambiguous, Anderson's work covers all of the right territories to captivate.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

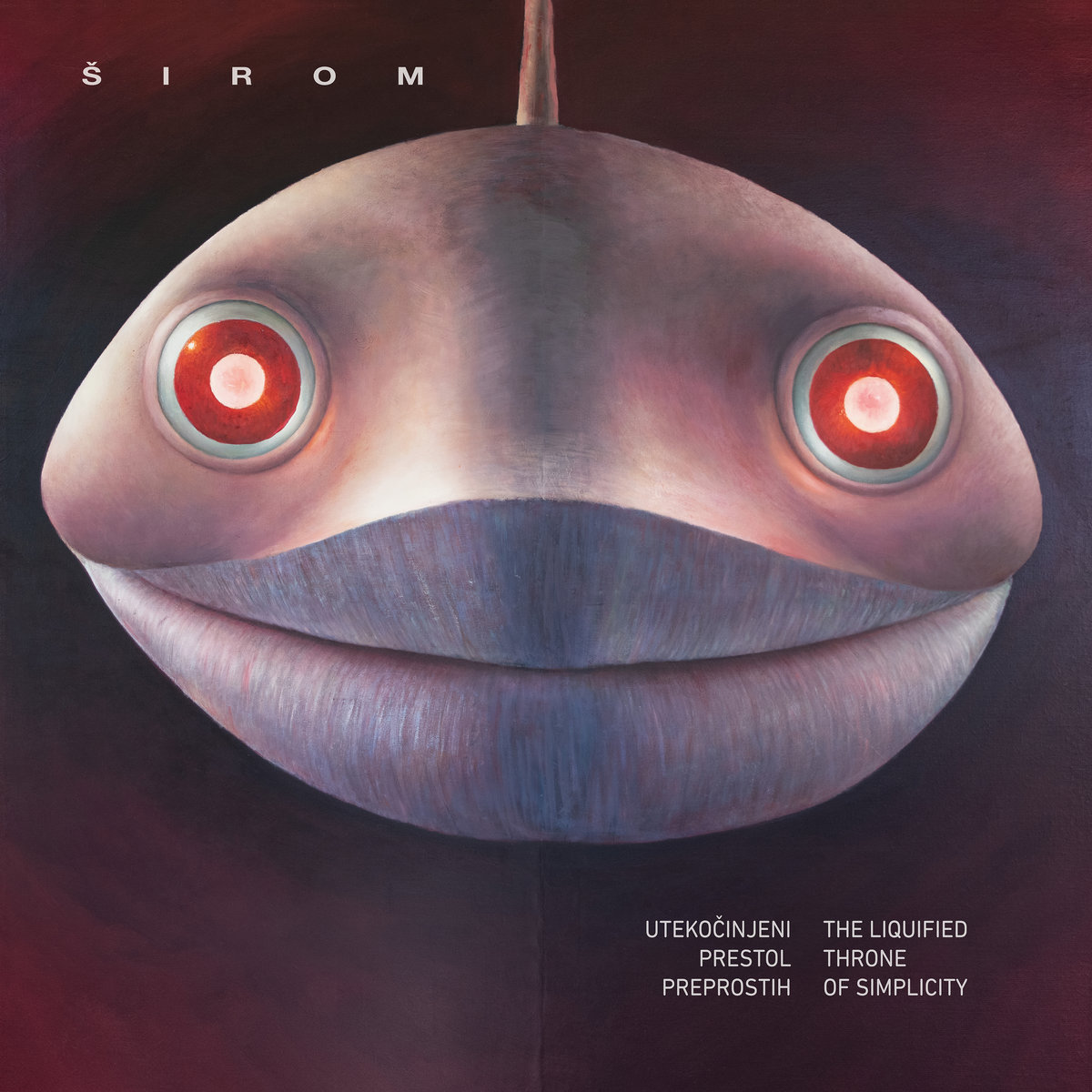

I feel like I got into this Slovenian "imaginary folk" trio a bit late, as 2019’s A Universe That Roasts Blossoms For A Horse was the first Širom album that I picked up. However, it also seems like each new album is the perfect time to discover Širom and those who join the party with this latest release are in for a real treat. Along with Belgium’s Merope and the scene centered around France’s Standard In-Fi and La Nòvia labels, Širom are one of the leading lights in a new wave of imaginative and adventurous international folk ensembles and this fourth album is their most expansive to date (“for the first time the trio…ignore the time constraints of a standard vinyl record to fashion longer, more fully developed entrancing and hypnotizing peregrinations”). Aside from making stellar use of their newly expanded song lengths, it feels like some delightful jazz influences have crept deeper into Širom’s DNA as well, as a couple of pieces feel like the various members trading wonderfully wild, visceral, and hallucinatory solos over strong, unconventional vamps (the album description also explicitly notes that Širom “echo the borderless, collective spirit of groups like Don Cherry's Organic Music Society and Art Ensemble of Chicago”). Obviously, that is enviable and excellent company to be associated with, but Širom’s influences transcend perceived boundaries of time and space so fluidly that trying to forensically determine the contents of their record collections is both hopeless and entirely beside the point. When they are at their best (which happens often here), Širom feel like a glimpse into an alternate timeline where the freewheeling adventurousness of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s never ended and everything just kept getting weirder, cooler, and more sophisticated forever (and record labels were delighted to foot the bill for anything that could potentially be the next The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter).

I feel like I got into this Slovenian "imaginary folk" trio a bit late, as 2019’s A Universe That Roasts Blossoms For A Horse was the first Širom album that I picked up. However, it also seems like each new album is the perfect time to discover Širom and those who join the party with this latest release are in for a real treat. Along with Belgium’s Merope and the scene centered around France’s Standard In-Fi and La Nòvia labels, Širom are one of the leading lights in a new wave of imaginative and adventurous international folk ensembles and this fourth album is their most expansive to date (“for the first time the trio…ignore the time constraints of a standard vinyl record to fashion longer, more fully developed entrancing and hypnotizing peregrinations”). Aside from making stellar use of their newly expanded song lengths, it feels like some delightful jazz influences have crept deeper into Širom’s DNA as well, as a couple of pieces feel like the various members trading wonderfully wild, visceral, and hallucinatory solos over strong, unconventional vamps (the album description also explicitly notes that Širom “echo the borderless, collective spirit of groups like Don Cherry's Organic Music Society and Art Ensemble of Chicago”). Obviously, that is enviable and excellent company to be associated with, but Širom’s influences transcend perceived boundaries of time and space so fluidly that trying to forensically determine the contents of their record collections is both hopeless and entirely beside the point. When they are at their best (which happens often here), Širom feel like a glimpse into an alternate timeline where the freewheeling adventurousness of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s never ended and everything just kept getting weirder, cooler, and more sophisticated forever (and record labels were delighted to foot the bill for anything that could potentially be the next The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter).

The album opens with one hell of a bombshell in the form of “Wilted Superstition Engaged in Copulation,” as the trio unleash an impressive run of killer solos over a pleasantly clattering, oddly timed percussion vamp. Given the exotic nature of the instrumentation and the multiple roles that each of the band members play, it can be quite a challenge to figure out who is doing what at any given moment, but Ana Kravanja’s alternately droning and gnarled viola themes are a definite and recurring highlight. The other highlights are a bit more challenging to wrap my mind around, as one stretch sounds like a buzzing, psychotropic duet between a strangled bagpipe and some Peruvian flutes, while another sounds like a rattling, delay-enhanced cacophony of violently jangled metal chimes. Naturally, there are some other inspired, hard-to-describe moments along the way as well, giving the piece the feel of a 20-minute performance in which a magician pulls increasingly weirder and more surprising things out of his hat. The band then shifts gears a bit for the more subdued “Grazes, Wrinkles, Drifts into Sleep,” as Kravanja unleashes a lovely melancholy viola melody over a quiet backdrop of intertwining balafon and banjo themes. There are plenty of compelling twists early on (sharp and/or ghostly harmonics and warbly, wordless vocals from Kravanja), but the big payoff comes when it shoots right past “psychotropic aviary” and intensifies into a buzzing and heaving crescendo of heavy acoustic drone.

Elsewhere, the trio ride a ritualistic-sounding “tribal” groove en route to a howling and visceral crescendo of tormented strings in “A Bluish Flickering” before surprising me again with a haunting and melodic banjo/viola coda. The last major piece on the album (“Prods the Fire with a Bone, Rolls over with a Snake”) veers into yet another intriguing bit of untrammeled stylistic terrain, as it sounds like a supernatural collision of birdsong-like vocals, Ravel-esque impressionist march, intricate banjo arpeggios, spacey squelches, and feral strings beautifully enlivened with harmonics and bow scrapes. Later, it eventually erupts into a furious maelstrom of tremolo-picked, violently strummed, and furiously bowed strings, but that too collapses to make way for a rolling groove augmented by cool percussion flourishes and circular viola arpeggios. Another impressively volcanic crescendo soon follows and when the dust settles, Širom ride off into the sunset with the rolling, warbling, and jangly outro of “I Unveil a Peppercorn to See It Vanish.” To my ears, the first three songs amount to a nearly unbroken hour of rustic and revelatory brilliance and I have absolutely no grievances with the other two pieces. Širom are an international treasure, as this album sounds like The Incredible String Band, Louise Landes Levi, and the entire Nonesuch Explorer series were mashed together in the best way possible (and with some killer psych touches thrown in for further icing on the cake).

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

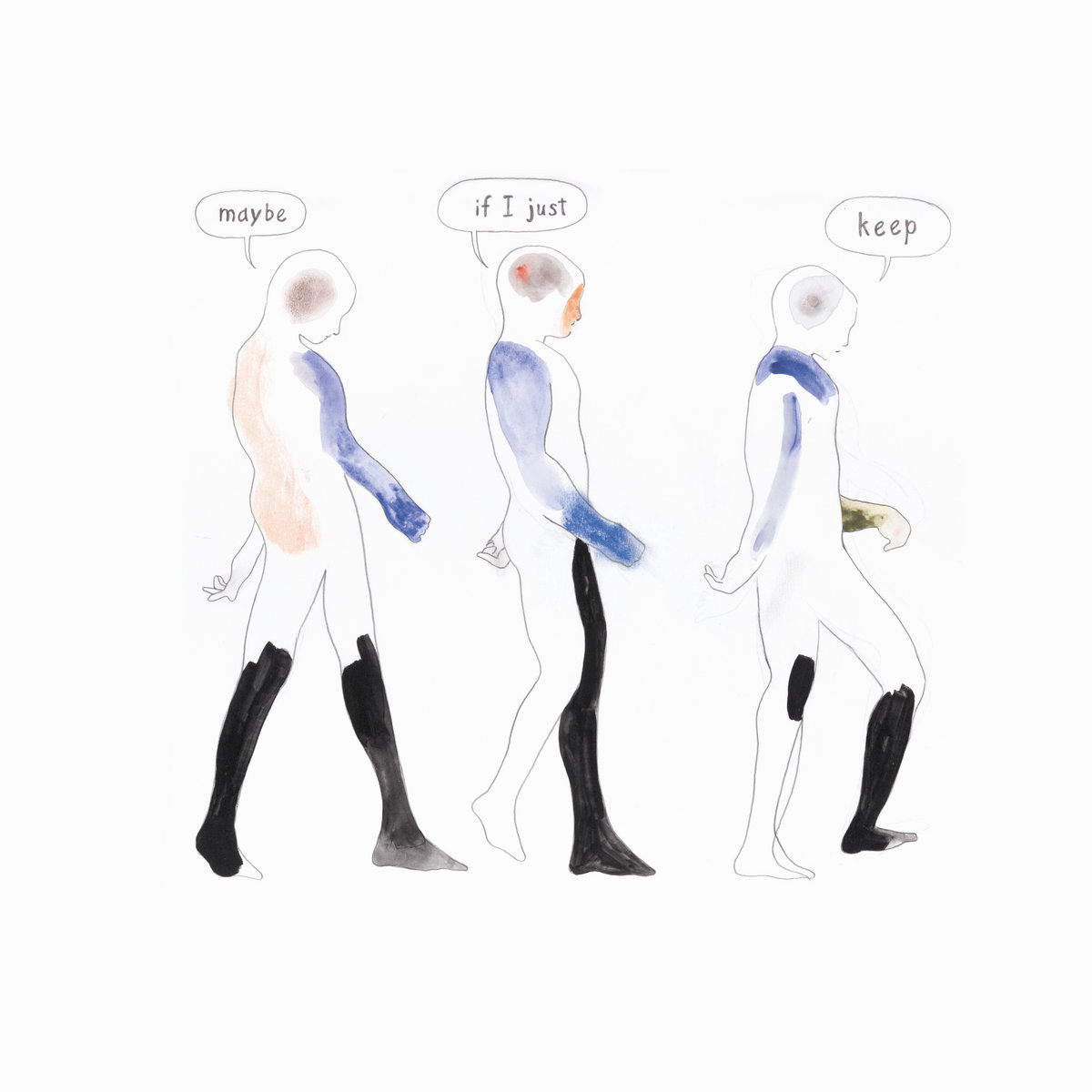

This latest album from the consistently fascinating Atkinson is yet another plunge into a vibrantly textured and otherworldly dreamspace, this time drawing inspiration from an abstract dialog between house and landscape. Or more specifically, "Inside and outside, different ways of orienting a body towards the world." In keeping with that theme, Atkinson "revisited twentieth-century women artists who variously chose, and were chosen by, their homes as a place to work." Naturally, there are some other conceptual layers as well (this being a Félicia Atkinson album, after all). One of the more interesting ones is the decision to give the album a name that resembles a "fake title of a fake Godard film." In an obvious sense, that is apt given how Image Langage feels like a film with no actual images, but Godard's mischievous meaning-dissolving weirdness is also manifested in how Atkinson wields and repurposes her sounds. In more concrete terms, that means that Atkinson deliberately used instruments alternately like field recordings or characters in a murky, surreal narrative and often reduces her voice to an unpredictably drifting and elusive presence. The overall effect is like being lost in a beautiful dream where an unreliable narrator periodically drifts in with riddle-like non-clues that only lead me deeper into Atkinson's eerie, soft-focus enigma.

This latest album from the consistently fascinating Atkinson is yet another plunge into a vibrantly textured and otherworldly dreamspace, this time drawing inspiration from an abstract dialog between house and landscape. Or more specifically, "Inside and outside, different ways of orienting a body towards the world." In keeping with that theme, Atkinson "revisited twentieth-century women artists who variously chose, and were chosen by, their homes as a place to work." Naturally, there are some other conceptual layers as well (this being a Félicia Atkinson album, after all). One of the more interesting ones is the decision to give the album a name that resembles a "fake title of a fake Godard film." In an obvious sense, that is apt given how Image Langage feels like a film with no actual images, but Godard's mischievous meaning-dissolving weirdness is also manifested in how Atkinson wields and repurposes her sounds. In more concrete terms, that means that Atkinson deliberately used instruments alternately like field recordings or characters in a murky, surreal narrative and often reduces her voice to an unpredictably drifting and elusive presence. The overall effect is like being lost in a beautiful dream where an unreliable narrator periodically drifts in with riddle-like non-clues that only lead me deeper into Atkinson's eerie, soft-focus enigma.

This album is billed as “an environmental record” about “getting lost in places imagined and real.” Naturally, one of the real places central to the album is Atkinson’s home on the “wild coast of Normandy” where much of the writing and recording took place (the rest occurred at a lakeside residency in Switzerland). I bring all this up because Image Langage has an unusually enigmatic and slippery aesthetic that blurs the line between songcraft and more abstract/outré fare. At times, the album can feel very “ambient,” but it is actually chasing something akin to impressionistic clairvoyance/clairaudience. While fully grasping the shades of meaning lurking within a Félicia Atkinson is often a tall order, Thea Ballard crafted quite an illuminating statement for the album’s description, noting that Image Langage evokes a visit to Atkinson’s seaside home in which we are “invited to witness Atkinson’s acts of seeing, hearing, and reading in a sonic double of the places they occurred.” In more practical terms, that means that the overall impression left by Image Langage is that of staying in a benignly haunted cottage populated by whispered voices, bleary drones, ephemeral flickers of piano melody, and hallucinatory manipulations of nature sounds. Unsurprisingly, I find that to be characteristically immersive and fascinating Atkinson territory, but Image Langage also has a handful of great individual pieces that transcend the baseline “ASMR-inspired ambient for well-read seaside ghosts” aesthetic. Amusingly, a case could be made that this is Atkinson’s “dub album,” as two of the strongest pieces share some common ground with artists like Pole and loscil.

My favorite piece is the album’s single, “Becoming A Stone,” which features a hushed monologue (“I believe that a fence will keep animals out, just outside the kitchen window") weightlessly drifting over a quiet bed of clicks, pops, a lazily repeating chord, and a wandering, bleary melody. Elsewhere, the more structured “The House That Agnes Built” is the loscil-esque piece, as Atkinson sensuously whispers over billowing, deconstructed dub centered around a sonar-like ping. Those subtle dub techno elements suit Atkinson’s aesthetic quite well, but there are a couple of drone-based pieces that are similarly strong. In particular, “The Lake is Speaking” is classic Atkinson, as it feels like a wandering piano melody is guiding me through a harmonically rich labyrinth of undulating dream drones. The title piece is yet another highlight, as hushed overlapping/doubled voices languorously bubble up from an uneasy backdrop of flute and/or harmonium drones. It all adds up to yet another wonderfully sublime album from a consistently compelling and endlessly evolving artist on a path entirely her own. Image Langage feels like getting a glimpse of someone’s most intimate journals, but only after an erasure poet got there first, leaving behind only a series of maddeningly enticing decontextualized fragments and a lingering sense of a beautiful mystery destined to remain forever unsolved.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

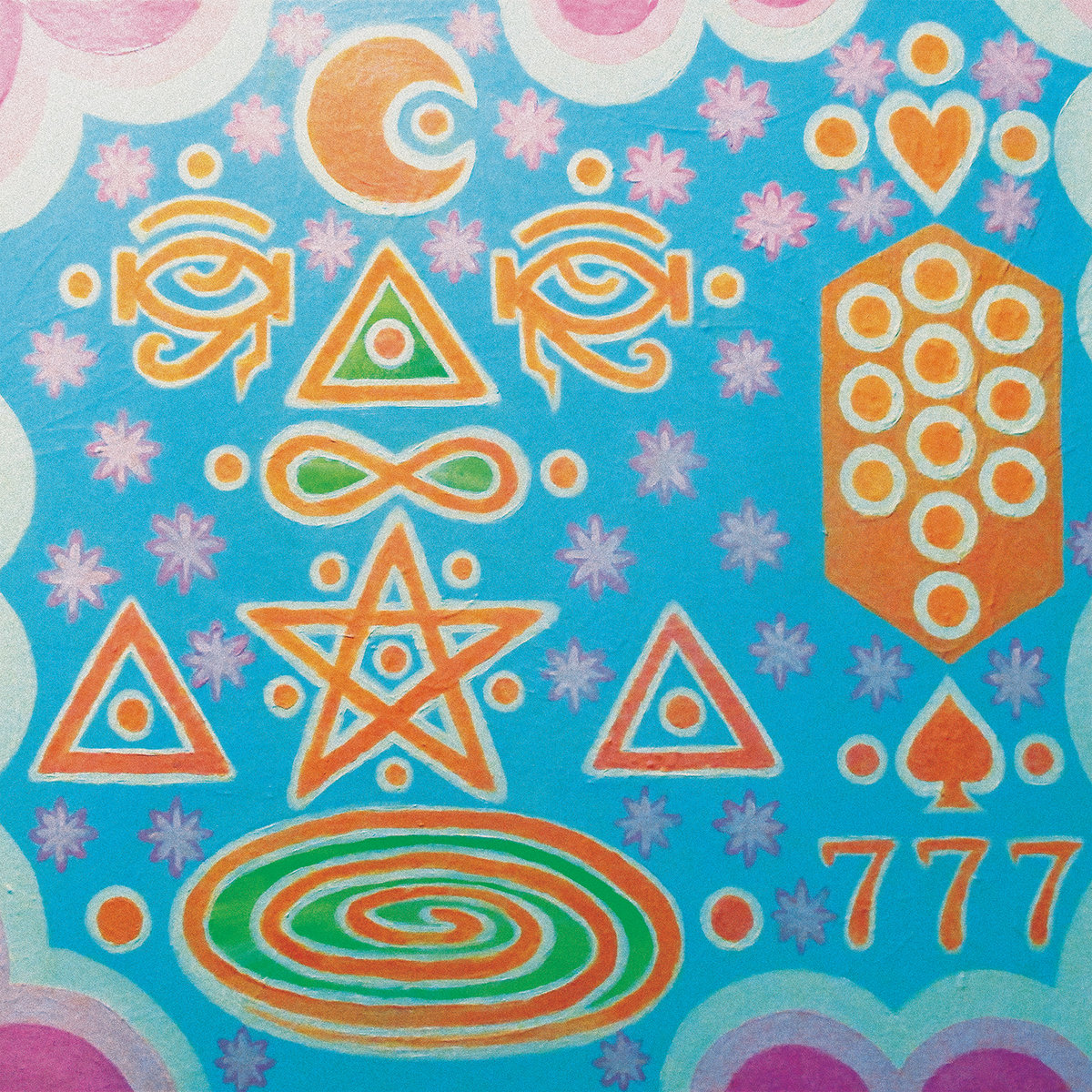

After a handful of teasing and divergent singles, Caterina Barbieri's first full-length on her own light-years imprint is finally here. To be honest, I had some early apprehensions about how well Spirit Exit would stack up against previous releases, as this is an unusual Barbieri album for a couple of significant reasons. The most obvious one, of course, is that this is the first of the Milan-based synth visionary's albums to feature vocal pieces. Equally significant is how the album was composed and recorded, however, as Barbieri's previous releases gradually took shape from her eternally evolving live performances. Spirit Exit, on the other hand, is "100% studio music, written and recorded amidst Milan's infamous, dramatic extremely strict two-month lockdown...at the very start of the pandemic in early 2020." The drama and darkness of the period unquestionably surface a lot on these pieces, but the unraveling of civilization was but one of Barbieri's major influences at the time, as Spirit Exit was also inspired by "female philosophers, mystics and poets spread across time...united in their strength at cultivating vast internal worlds." Barbieri is no slouch at cultivating vast internal worlds herself, as evidenced by the "psycho-physical effects of pattern-based repetition" explored in her earlier work and the second half of the album features several pieces that feel like instant classics. Some of Barbieri's attempts to expand her vision into more pop and dance-inspired places work a bit less well to my ears, which ultimately gives Spirit Exit a bit of a "transitional album" feel, but those pieces may someday dazzle me after being further honed by live performances or inspired collaborations (she previously managed to floor me once with Fantas and again with Fantas Variations, after all).

After a handful of teasing and divergent singles, Caterina Barbieri's first full-length on her own light-years imprint is finally here. To be honest, I had some early apprehensions about how well Spirit Exit would stack up against previous releases, as this is an unusual Barbieri album for a couple of significant reasons. The most obvious one, of course, is that this is the first of the Milan-based synth visionary's albums to feature vocal pieces. Equally significant is how the album was composed and recorded, however, as Barbieri's previous releases gradually took shape from her eternally evolving live performances. Spirit Exit, on the other hand, is "100% studio music, written and recorded amidst Milan's infamous, dramatic extremely strict two-month lockdown...at the very start of the pandemic in early 2020." The drama and darkness of the period unquestionably surface a lot on these pieces, but the unraveling of civilization was but one of Barbieri's major influences at the time, as Spirit Exit was also inspired by "female philosophers, mystics and poets spread across time...united in their strength at cultivating vast internal worlds." Barbieri is no slouch at cultivating vast internal worlds herself, as evidenced by the "psycho-physical effects of pattern-based repetition" explored in her earlier work and the second half of the album features several pieces that feel like instant classics. Some of Barbieri's attempts to expand her vision into more pop and dance-inspired places work a bit less well to my ears, which ultimately gives Spirit Exit a bit of a "transitional album" feel, but those pieces may someday dazzle me after being further honed by live performances or inspired collaborations (she previously managed to floor me once with Fantas and again with Fantas Variations, after all).

In classic “Fantas” fashion, Spirit Exit continues the fine Barbieri tradition of leading off her albums with an absolutely killer opener. In this case, the masterpiece is “At Your Gamut,” which resolves into something resembling beatless deconstructed house music after a brief snarl of sputtering, howling entropy. The heart of the piece is its bittersweet synth melody, however, which leaves psychotropic vapor trails and tendrils of arpeggios and countermelodies in its wake. Aside from being a great song, it is a perfect illustration of why Barbieri is on a plane all her own, as it is a fiendishly complex feast of interlocking melodies, shifting textures, and gleamingly futuristic, neon-lit beauty. Notably, “At Your Gamut” also inspired Barbieri’s first foray into sampling, as “it later gets crushed, accelerated and unrecognizably transformed into the ghostly hook” of yet another stellar piece (“Terminal Clock”). While earlier pieces on the album merely flirt with dance music, “Terminal Clock” is the piece in which Barbieri finally goes all in with absolutely sublime results, as swooning vocal fragments beautifully collide with a lurching kick drum thump, pulsing chords, melodic strings, and some wonderfully gnarled and tortured-sounding textures. To my ears, it is an instant stone-cold classic of outsider techno and an enticing glimpse of where Barbieri may be headed next. Remarkably, however, “Terminal Clock” is sandwiched between two other gems of similarly high caliber: “Life At Altitude” and “The Landscape Listens.”

“Life At Altitude” is something of a throwback to Barbieri’s earlier work, as it is essentially just a single killer arpeggio pattern enlivened with endlessly shifting textures and organically waxing and waning passages of intensity. Needless to say, it is spacey, psychedelic, and futuristic-sounding in all the right ways. “The Landscape Listens” is also quite spacey and hallucinatory, but it takes a very different path to get there, as bleary, hiss-soaked swells of melodies feel like they are straining to break through a bulging and tearing dimensional barrier. Despite that, it is an unexpectedly warm, tender, and meditative piece that culminates in a lovely swooping and swooning final act. For those keeping score at home, that means that four out of Spirit Exit’s eight songs are absolutely goddamn perfect and probably essential listening for anyone actively interested in the current cutting edge (or future) of electronic music. The remaining four pieces are a bit more of an inspired mixed bag, as they each miss the mark for me in one way or another, yet generally still have at least one extremely cool idea or theme at their heart. The best of the lot is the epic “Knot of Spirit (Synth Version),” in which a dreamy melody lazily falls through a backdrop of blurred and flickering stars like a comet before transforming into a more structured arpeggio workout for its second half. The remaining three pieces are all vocal ones whose only crime is that they tend to be a be bit too dramatic for my taste (likely influenced by the “end times” feel of the early months of the pandemic), but I can definitely foresee that side of Barbieri’s work reaching a much wider audience once she figures out how to better to play to her strengths, as her potential seems damn near limitless at this stage.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

John McGuire has an impressive background in the study and evolution of electronic music: not least his time with Stockhausen at Darmstadt summer schools and subsequent commissions for German radio. Pulse Music is a unique and lively collection (1975-79) that skates across similar post-minimalist terrain as Reich and Riley and kills any lingering debate about the merits of serialism. McGuire created pulse layers in the studios of WDR and the University of Cologne, which to this day possess astounding clarity and separation, allied to marvelous tempo changes.

John McGuire has an impressive background in the study and evolution of electronic music: not least his time with Stockhausen at Darmstadt summer schools and subsequent commissions for German radio. Pulse Music is a unique and lively collection (1975-79) that skates across similar post-minimalist terrain as Reich and Riley and kills any lingering debate about the merits of serialism. McGuire created pulse layers in the studios of WDR and the University of Cologne, which to this day possess astounding clarity and separation, allied to marvelous tempo changes.

One visual image to explain McGuire’s motivation is the creation of waves coming from left to right and interweaving, waves emerging as if from a fountain and dispersing as if into a bottomless hole. Only the composer himself can know for sure if he achieved his musical goals but God knows he cannot be faulted for the extensive efforts he undertook in pursuit of his vision. I could devote a thousand words to his compositional technique and musical methodology without grasping it fully. On paper, at least, it’s insanely more complex than such successful examples as “record a tramp, loop his singing with minimal orchestral backing”, "Mick Stubbs had read a book called The Dawn of Magic,” or even “hum bits, nap, and write surreal poetry while cowed musicians spend months honing the sounds.”

The outlier here is “Pulse II,” a necessarily slower piece in order to allow for a one-off performance (included) by orchestra with four pianos and organ. The time structures of the other three pieces sound as if they were devised by someone in the throes of a fever dream, whereas for “Pulse II” the fever has broken. The piece provides interesting variety yet illustrates the exciting benefits of the studio for realizing the incredibly precise glory of McGuire’s vision.

His essay explaining how “Pulse III'' was made—in the age before studios were computerized—is a dizzying account of the effort and calculation required. Since he was concerned with creating motion rather than a particular sound, John McGuire decided this could not be achieved by acoustical instruments or the human voice. What was needed—and here clarity is swiftly engulfed as simple terms and their explanations pile up and intertwine—was the creation of overlapping symmetrical waves, an uninterrupted stream, a spatial motion with no apparent beginning or end, two series of pulses each with a different pitch and alternating on each pulse. The pulse series were interlocked within their regulating envelopes and overlapped to form a continuous looping motion in space. [This is the basic account before the explanation broadens and deepens with reference to envelope frequency, coincidence markers, pitch and interval, harmonic tuning, sine tones, sounding models, simultaneity, succession, “product” and “coincidence” frequencies”, the 3:5 ratio, drone package, melodic elaboration, hexachords, subharmonic fundamentals, attack and decay transients, cross fading, volume curves, and (possibly my favorite) velocity constellation. ] A key component which I can at least pretend to understand is the creation—using 8 channel mixing—of a trigger pulse circuit to enable precision synchronization of various looped, er, things.

None of this would mean much if the music itself had not turned out to be so accessible and inspired. Pulse Music is a labyrinth of kaleidoscopic detail, mathematical patterns, and organic flow. It is an early contender for reissue of the year.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This long-awaited follow up to Malone's 2019 cult masterpiece The Sacrificial Code is an unexpected blend of the familiar and the unfamiliar, as the Stockholm-based composer trades in her now signature pipe organ for "a complex electroacoustic ensemble." While that new approach certainly features an ambitiously expanded instrumental palette (trombone, bass clarinet, boîte à bourdon. sinewave generator, and ARP 2500 synth), Living Torch is still instantly recognizable as Malone's work both stylistically and structurally. Notably, the piece was "commissioned by GRM for its legendary loudspeaker orchestra," which makes a lot of sense in hindsight, as Living Torch sometimes improbably feels like the work of a drone-obsessed medieval organist who somehow managed to get ahold of Sunn O)))'s gear and some ancient battle horns. Given those enhancements, Living Torch can reasonably be described as a more conspicuously doom-inspired release than The Sacrificial Code. Admittedly, that takes this particular album a bit out of my own personal comfort zone, but I love it anyway and remain firm in my belief that Malone is one of the most singular and fascinating composers of her generation.

This long-awaited follow up to Malone's 2019 cult masterpiece The Sacrificial Code is an unexpected blend of the familiar and the unfamiliar, as the Stockholm-based composer trades in her now signature pipe organ for "a complex electroacoustic ensemble." While that new approach certainly features an ambitiously expanded instrumental palette (trombone, bass clarinet, boîte à bourdon. sinewave generator, and ARP 2500 synth), Living Torch is still instantly recognizable as Malone's work both stylistically and structurally. Notably, the piece was "commissioned by GRM for its legendary loudspeaker orchestra," which makes a lot of sense in hindsight, as Living Torch sometimes improbably feels like the work of a drone-obsessed medieval organist who somehow managed to get ahold of Sunn O)))'s gear and some ancient battle horns. Given those enhancements, Living Torch can reasonably be described as a more conspicuously doom-inspired release than The Sacrificial Code. Admittedly, that takes this particular album a bit out of my own personal comfort zone, but I love it anyway and remain firm in my belief that Malone is one of the most singular and fascinating composers of her generation.

This piece, which is split into two parts to accommodate the vinyl format, premiered in "complete multichannel form at the Grand Auditorium of Radio France in a concert entirely dedicated to the artist." I imagine it was quite an immersive and amazing performance for those lucky enough to be in attendance, yet I suspect my home-listening experience is but a pale shadow of the intended one, as my sound system falls a bit short of the GRM's Francois Bayle-designed Acousmonium (a "utopia devoted to pure listening"). Given that the loudspeaker orchestra's entire raison d'etre is to facilitate "immersion" and "spatialized polyphony," I cannot think of a more deserving commission recipient than Malone, as few contemporarily composers are more devoted to understanding and maximizing the physics of sound than Malone. In fact, I suspect there is at least one notebook packed with details about how the various frequencies of the shifting sustained tones interact to create a vibrant host of intentional overtones and oscillations. There are a number of other intriguing and cerebral things colliding here as well, as Living Torch draws from "multiple lineages including early modern music, American minimalism, and musique concrète" and also explores "justly tuned harmony," "canonic structures," "the polyphony of unique timbres," "the scaling of dynamic range," and "the revelation of sound qualities." Admittedly, I will just have to take Malone's word for some of that, but I can definitely appreciate the endlessly shifting, slow-motion beauty of the finished piece.

The album's first half opens with the expected foundation of slow-motion drones, throbbing bass tones, and subtly shifting oscillations, but soon heads into terrain that feels like some kind of majestic post-battle elegy from centuries past. As with all Malone releases, however, much of the magic lies in the textures and subtle transformations and how much I get out of the piece depends a lot on how closely I listen to the details. As it unfolds further, the piece gradually blossoms into something like a slowly seething psychedelic cloud or a series of deep cosmic exhalations centered around a quietly flickering and undulating central chord. The album's second half basically picks up right where the first half left off, but the addition of a subtle, minor key bass pattern makes it feel like an especially blackened, slow-motion strain of post-rock. It does not take long before it becomes something more gnarled, seething, and distorted though. While I realize that Malone is originally from Colorado, it is clear that she has been living in Scandinavia long enough for black metal to become part of her DNA, as much of Living Torch's second act evokes a scene akin to black smoke lazily curling over the smoldering remnants of a torched cathedral as the final rays of a blood red sunset fade in the background. Similar to my imagined sunset, many of the drones fade away in the piece's final moment to reveal a tender, hauntingly beautiful closing passage. That last bit provides a satisfying (if understated) pay off, which I very much appreciate, but the entire piece is a sustained illustration of why Kali Malone is so wonderful and singular, as her control, patience, and attention to detail are unparalleled and her vision is uniquely her own. Tentatively, I still think I prefer The Sacrificial Code, but this one seems to be growing on me more with each listen and I am increasingly convinced that Malone is some kind of formidable new half-sorceress/half-architect breed of electroacoustic composer.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

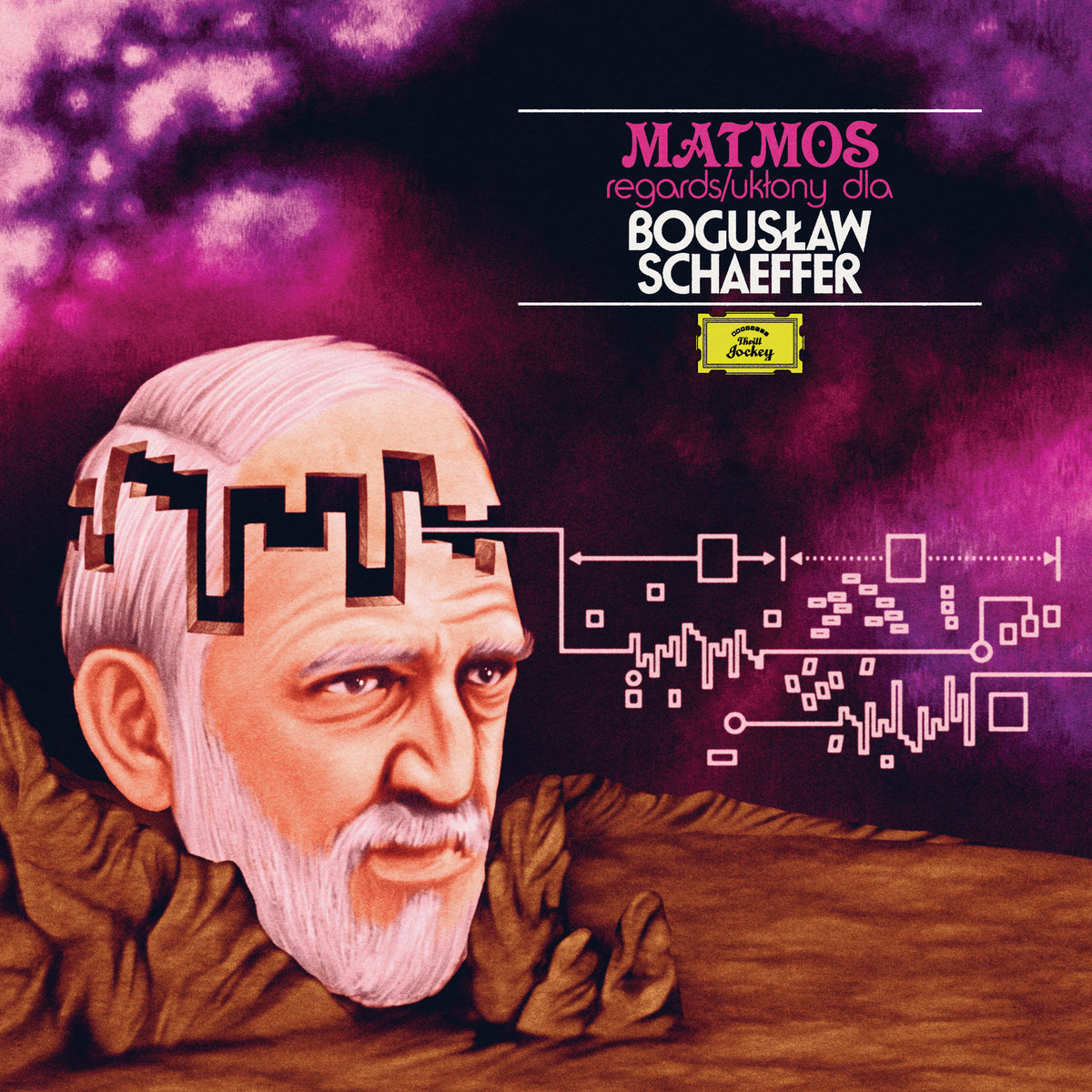

On this latest full-length, the perennially eclectic and boldly adventurous duo of Drew Daniel and MC Schmidt take a break from mining weird and esoteric source material to focus their energies on paying homage to underheard Polish composer and Krzysztof Penderecki associate Bogusław Schaeffer. Matmos were given full access to work their mindbending magic on Schaeffer's complete recorded works and the resultant album is as characteristically unpredictable and hard-to-categorize as ever: instead of remixing or reinterpreting the Polish composer's work, Matmos instead took "tissue samples of DNA from past compositions" and "mutated them into entirely new organisms that throb with an alien vitality." Put another way, Regards/Ukłony dla Bogusław Schaeffer attempts to create a conversation or bridge between the "utopian 1960s Polish avant-garde" and "the contemporary dystopian cultural moment." That is certainly intriguing and fertile terrain for a Matmos album, but the resultant songs wound up somewhere even more delightful and confounding than usual, often approximating a collision between fragmented exotica, kosmische, and a Kubrickian sci-fi nightmare. Naturally, that will be very appealing territory for most long-time Matmos fans, as this album is an especially inspired "everything and the kitchen sink" tour de force of quite disparate stylistic threads woven together in playfully disorienting and mischievous fashion by an talented international cast of virtuousos, eccentric visionaries, and plunderphonic magpies.

On this latest full-length, the perennially eclectic and boldly adventurous duo of Drew Daniel and MC Schmidt take a break from mining weird and esoteric source material to focus their energies on paying homage to underheard Polish composer and Krzysztof Penderecki associate Bogusław Schaeffer. Matmos were given full access to work their mindbending magic on Schaeffer's complete recorded works and the resultant album is as characteristically unpredictable and hard-to-categorize as ever: instead of remixing or reinterpreting the Polish composer's work, Matmos instead took "tissue samples of DNA from past compositions" and "mutated them into entirely new organisms that throb with an alien vitality." Put another way, Regards/Ukłony dla Bogusław Schaeffer attempts to create a conversation or bridge between the "utopian 1960s Polish avant-garde" and "the contemporary dystopian cultural moment." That is certainly intriguing and fertile terrain for a Matmos album, but the resultant songs wound up somewhere even more delightful and confounding than usual, often approximating a collision between fragmented exotica, kosmische, and a Kubrickian sci-fi nightmare. Naturally, that will be very appealing territory for most long-time Matmos fans, as this album is an especially inspired "everything and the kitchen sink" tour de force of quite disparate stylistic threads woven together in playfully disorienting and mischievous fashion by an talented international cast of virtuousos, eccentric visionaries, and plunderphonic magpies.

My knowledge of Bogusław Schaeffer's work is quite minimal, which makes sense, given that he is not particularly well known outside of Poland. However, I have previously encountered fragments of his ouevre through Bôłt's "Polish Radio Experimental Studio" reissue campaign (as well as an unknowing exposure via David Lynch's Inland Empire). Fittingly, Bôłt founder Michał Mendyk was the spark behind this endeavor (as well as providing some presumably much-needed translation assistance). To Mendyk's credit, reshaping and cannibalizing Schaeffer's work turned out to be an ideal project for Daniel and Schmidt to throw themselves into, as the end result is quintessential Matmos. Granted, the duo's characteristically morbid and/or gleefully ridiculous sound sources are absent here, but Regards checks a lot of other boxes on my personal checklist for an inspired Matmos album (kitsch colliding with high art, rigorous scholarship and compositional vision colliding with plunderphonic mischief, etc.). The opening "Resemblage" provides a representative window into the album's baseline aesthetic, approximating a squelchy strain of post-modernist exotica that evokes the feeling of being serenaded by an all-cyborg Xavier Cugat Orchestra in a psychedelic cave. My favorite pieces all follow soon after, as Regards boasts quite a killer first half.

In “Cobra Wages Shuffle,” for example, Matmos unleash something akin to mutant electrofunk played with bath toys that later makes surprise detours into deep space horror, android ASMR, and fragmented NWW-style sound collage. Elsewhere, "Few, Far Chaos Bugles" brings in Turkish multi-instrumentalist Ulas Kurugullu for a mindbending melange of Eastern European folk, tenacious typewriter, Martin Denny, and Thirlwell-esque artificial-sounding horn blurts that evokes the feeling of having a psychotic breakdown on a moonlit beach because incomprehensible alien transmissions are being relentlessly beamed into my head. "Flight to Sodom" is yet another hit, capturing Matmos and instrument builder Will Schorre in an unusually poppy mood, as they steer a lurching kickdrum beat and burbling kosmische synths into a Rashad Becker-esque psychotropic bestiary (fitting, given that Becker himself mastered the album). While I do prefer the album's first half to the second, there are not any pieces that miss the mark–only ones that feature a different balance of broken/fragmented avant-gardism and conventionally enjoyable grooves and melodies. As with all Matmos releases, the big caveat is that Regards is an unrepentantly challenging and kaleidoscopic listening experience, but the rampant exotica touches nicely balance the duo's more alienating tendencies to make this one of the more fun and consistently fascinating albums in the duo's oft-difficult discography.

Sounds can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This is my first deep immersion into Joëlle Vinciarelli & Eric Lombaert's deeply unconventional "free metal" duo, but I have long been a fan of the pair's noise/drone band La Morte Young (as well as Vinciarelli's repeat collaborations with My Cat is an Alien). Notably, there is absolutely nothing recognizably "metal" about this latest release, as the closest kindred spirits are probably outer limits psychonauts like the LAFMS milieu or Borbetomagus. However, even those signposts are inadequate at conveying how far Talweg have descended into their own personal rabbit hole with this album, as these four pieces feel both unstuck in time and decidedly pagan/occult-inspired (which makes sense, given Vinciarelli's passion for collecting unusual and ancient instruments). Further muddying the waters, this album arguably captures the duo in "soundtrack mode," as two of the pieces are early/rehearsal versions of pieces composed for a Monster Chetwynd exhibition, while a third borrows a nursery rhyme from Marcel Hanoun's "Le Printemps" as its central theme. While "rehearsals for an exhibition soundtrack" admittedly does not sound all that appealing on paper, these recordings are quite compelling in reality, as Des tourments si grands often feels like a remarkably inspired and deeply unconventional stab at outsider free jazz. Fans of Vinciarelli's work with MCIAA will definitely want to investigate this one, as it journeys into similarly alien territory, but the addition of Lombaert's killer drumming takes that aesthetic in a far more explosive and visceral direction.

This is my first deep immersion into Joëlle Vinciarelli & Eric Lombaert's deeply unconventional "free metal" duo, but I have long been a fan of the pair's noise/drone band La Morte Young (as well as Vinciarelli's repeat collaborations with My Cat is an Alien). Notably, there is absolutely nothing recognizably "metal" about this latest release, as the closest kindred spirits are probably outer limits psychonauts like the LAFMS milieu or Borbetomagus. However, even those signposts are inadequate at conveying how far Talweg have descended into their own personal rabbit hole with this album, as these four pieces feel both unstuck in time and decidedly pagan/occult-inspired (which makes sense, given Vinciarelli's passion for collecting unusual and ancient instruments). Further muddying the waters, this album arguably captures the duo in "soundtrack mode," as two of the pieces are early/rehearsal versions of pieces composed for a Monster Chetwynd exhibition, while a third borrows a nursery rhyme from Marcel Hanoun's "Le Printemps" as its central theme. While "rehearsals for an exhibition soundtrack" admittedly does not sound all that appealing on paper, these recordings are quite compelling in reality, as Des tourments si grands often feels like a remarkably inspired and deeply unconventional stab at outsider free jazz. Fans of Vinciarelli's work with MCIAA will definitely want to investigate this one, as it journeys into similarly alien territory, but the addition of Lombaert's killer drumming takes that aesthetic in a far more explosive and visceral direction.

Up Against the Wall, Motherfuckers!

The album is divided into four separate longform pieces that always extend for at least fifteen minutes of shapeshifting psychotropic magic. Picking a favorite is damn near impossible, as every single piece eventually gets somewhere wonderful, but my current feeling is that the closing "où l'on souffre, des tourments si grands que..." is the highlight that best captures the duo at the height of their powers. It initially calls to mind a duet between a free jazz drummer and an orchestra of demonic air raid sirens, but the howling maelstrom is soon further enhanced by the sing-song nursery rhyme at its heart, resulting in something that sounds like a somnambulant French Vashti Bunyan loopingly intoning the same lines over and over again inside a gnarled extradimensional nightmare. Somehow the piece only gets better from there, as a descending chord progression and a stomping, crashing beat take shape as Vinciarelli unleashes a viscerally feral-sounding trumpet solo. Notably, it is the only piece on the album where I can hear any real trace of the pair's metal inspirations, as it feels like a heavy doom metal jam played on the wrong instruments (coupled with a pointed avoidance of all genre tropes, of course). In short, it rules, but the other three songs all come quite close to scaling similarly lofty heights.

In the opener, for example, Talweg approximate an unholy mash-up of ancient pagan bell ceremony, lysergic aviary, supernaturally possessed music box, and a Siren luring me through an ambient fog towards the Black Lodge from Twin Peaks. Elsewhere, "comme une éponge, que l'on plonge" initially kicks off in similar "strangled, uneasily viscous-sounding ceremonial trumpet meets free jazz drumming" territory, but then dissolves into a wonderfully simmering groove of buzzing, psychotropic drones and a skittering, off-kilter beat enlivened with wild, virtuosic fills before reigniting for a gloriously volcanic finale. The remaining piece, "dans un gouffre, plein de soufre," is yet another top-tier mindfuck, gradually evolving from "droning harmonium sea shanty" to "gently undulating ambient/noir-jazz psychedelia" to "roaring extradimensional nightmare storm" en route to an unexpectedly meditative coda that sounds like a train slowly chugging its way through a phantasmagoric landscape of raining crystals. The one caveat, of course, is that this album is quite a challenging, dissonant, and intense ride, but that should be welcome terrain for fans of the duo's other activities and Talweg are extremely fucking good at what they do. It is a real treat to encounter such otherworldly beauty and heady psychedelia delivered with white-knuckled elemental power and masterfully controlled violence.

Sounds can be found here.

Read More