- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

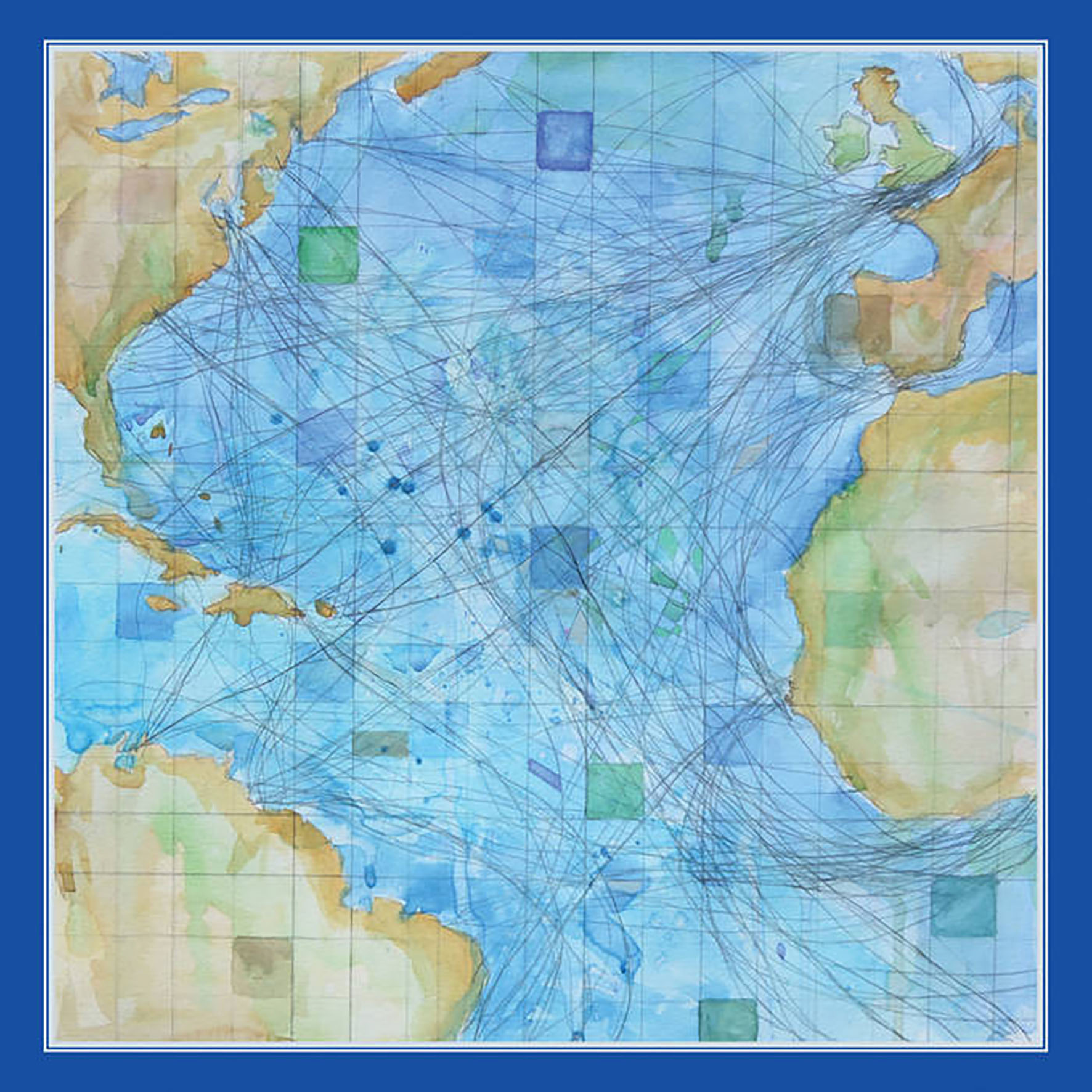

Somehow I have managed to remain largely unfamiliar with Shane Parish's work until now, which nicely set the stage for me to be properly blindsided by this latest release. That said, I am not sure a deep familiarity with Parish's previous albums would have changed all that much, as this album is quite an adventurous departure from his expected fare in some significant ways. The biggest twist, of course, is that Liverpool is essentially an album of old sea shanties. While that probably is not something I would have actively sought out on my own, I am damn glad that this album found me, as Parish's ingenious instrumental arrangements transform an ostensible curiosity into a goddamn revelation. Crucially, Liverpool does not sound at all like an album of sea shanties, as Parish merely borrowed their vocal melodies and made said melodies the backbone for a killer solo guitar album that favorably calls to mind everyone from Tortoise to Richard Bishop to Bill Orcutt (and manages to do it quite seamlessly). In hindsight, it is downright miraculous that other artists have not been making albums in this vein for years, as it is such a perfect and obvious starting point for greatness (in the right hands, at least). Parish essentially just found a bunch of timeless, poignant melodies waiting to be borrowed and he wisely embraced them. With such beautiful raw material as a starting point, it is hard to imagine that any good guitarist could have blown it and made a bad album, but it is similarly hard to imagine anyone else making an album as uniformly stellar as Liverpool: an excellent idea matched with even more excellent execution.

Unlike most traditional sea shanties, the opening "Liuerpool" erupts from the speakers as a squall of guitar noise and cymbal flourishes before settling into a simmering groove that feels like an darkly jazzy strain of post-punk. Naturally, the appearance of Parish's shimmering and hazy guitar melody only makes things better, but I was surprised at the central role that guest drummer Michael Libramento plays in the song's success, as "Liuerpool" sounds more like the work of a tight band of virtuosos than something that is ostensibly a solo guitar album. In fact, Libramento's presence proves to be quite a reliable harbinger of greatness throughout the album. as the tom-driven "Venezuela" and the explosive "Haul Away Joe" are also clear album highlights. Notably, none of the three pieces I have mentioned thus far resemble each other much at all, as "Venezuela" calls to mind Sublime Frequencies-damaged surf guitar, while "Haul Away Joe" feels like the dueling guitar crescendo of an epic psych rock masterpiece. Elsewhere, "Randy Dandy O" delves into incendiary Orcutt territory when its central melody gives way to a flurry of open strings, wild bends, pull-offs, and slashing chords. "Black Eyed Susan" is yet another favorite, as Parish combines ringing arpeggios, muted strums, and a nimbly dancing lead melody with a casual looseness that feels effortless. I am also quite fond of second-tier highlight "Santy Anno," as Parish quickly casts aside the central melody to unleash a likable (if conventional) guitar solo over a chopped and stuttering backdrop that sounds like a helicopter mated with some abstract shoegaze à la lovesliescrushing. The remaining three songs are enjoyable too, but they lack a bit of the pizzazz of their neighbors. However, I could easily see them emerging from Parish's current tour beautifully transformed by some kind of road-tested creative breakthrough. After listening to some of the traditional versions of these pieces and finding them nearly unrecognizable, it seems like major creative breakthroughs must be a somewhat common occurrence for Parish. In any case, Liverpool is a wonderful and oft-surprising release and Shane Parish now joins Orcutt, Daniel Bachman, and Sarah Lipstate in the pantheon of wildly inventive solo guitarists that I will be actively following for years to come.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This is the debut album for Claire M. Singer's Organ Reframed imprint, which will now enable home listeners to experience a bit of her singular music festival of the same name. While the festival itself has been going on since 2016, I can understand why Singer did not make the leap into releasing albums until now, as I imagine it is quite a challenge to translate the site-specific acoustic pleasures of Union Chapel's famed hydraulic organ onto a CD. Also, solo organ albums have only recently begun to come into vogue (and I suspect Singer's efforts played a key role in that). Thankfully, the stars seem to now be in proper alignment for such an endeavor, as artists like Kali Malone, Lawrence English, and Sarah Davachi have spent the last few years turning adventurous ears organ-ward and the reigning queen of minimalism (Radigue) is currently in the prime of her "acoustic instrumentation" era. Unsurprisingly, composing for organ has not resulted in a newly bombastic and maximalist Radigue, as she remains unswervingly devoted to Occam's guiding principle of "simple is always better." In fact, this album is probably a strong contender for one of Radigue's most minimal compositions to date. That may test the patience of some casual Radigue listerers, but those attuned to her slow-burning drone majesty will find much to love, as she is in peak form here.

This is not the first album in Radigue's "Occam Ocean" series that I have heard, but this is the first time that I learned about the origin of its curious title. Naturally, the "Occam" part is a reference to William of Ockham's timeless razor (the law of economy), but I did not know that the "ocean" bit was because Radigue is drawing much of her inspiration from water and waves these days. That makes sense and knowing that reveals further depth to this series. Also, given Radigue's history with Buddhism and its focus on mindfulness and the interconnectedness of all things, this series can be viewed as a sort of an artistic culmination of the themes and philosophies that have shaped her life as a whole. In more concrete terms, Radigue's recent work is driven by the "transcendent beauty" that she finds in the "micro beats, pulsations, harmonics, and subharmonics" that result when sound waves interact. Another central belief of Radigue's is that written music is an abstraction and that it is the performer that ultimately breathes life into it She also notes that "no two performers, playing the same instrument, have the same relationship with that instrument," so it was a significant choice that return collaborator/ONCEIM director Blondy was chosen to perform the piece.

Speaking of Blondy, I am quite curious about how technically demanding this piece was to play. My guess is "very," as it could easily be mistaken for a single sustained and droning chord with casual listening, but closer listening reveals that it is endlessly evolving and constantly creating subtle new sonic phenomena despite it being damn near imperceptible to tell when new notes are being added. In fact, the entire mood of the piece sneakily undergoes at least two dramatic transformations over the course of its 44 minutes, slowly moving from a stark, almost futuristic-sounding introduction of shuddering bass throbs towards a surprisingly hallucinatory finale of blearily celestial-sounding drones and insectoid whine. In between those two poles, there are passages that call to mind a surveillance beam slowly sweeping across a desolate wasteland or a gorgeous slow-motion sunrise and it never feels anything less than totally organic and seamless. And, of course, the piece's unhurried, meditative journey continually reveals additional subtle layers of harmonic complexity with deep listening. Given the near-geologic timescale and the ultra-minimal nature of this piece, it probably is not the ideal introductory Radigue album for the curious, but those already attuned to her work will likely be spellbound by the exacting and patient virtuosity on display (I certainly was). Occam XXV sets the bar intimidatingly high for whoever gets tagged for Organ Reframed's second release.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest full-length from Mark Nelson's long-running and unpredictably shapeshifting project is a collection of understated, near-ambient solo guitar instrumentals that Kranky describes as the culminating release of the composer's "romantic minimalism" side. It certainly is a languorously meditative and unrepentantly lowercase suite of songs, blurring the lines between an "ageless, scarred" Americana and dreamlike ambient drift. Significantly, the album was recorded during the first summer of the pandemic, as Nelson views these songs as a sort of "'lighthouse music,'" radiance cast from a stable vantage point, sending 'a signal to help others through rocks and dangerous currents.'" Given its gently minimal, near-ambient "lone guitar in the fog" aesthetic, The Patience Fader is likely to be something of a polarizing release: it falls dangerously close to calming Windham Hill-style prettiness a couple of times, but it can also feel incredibly poignant and sublime if one chooses to listen deeply enough. While it feels weird to describe music this quiet and slow-moving as "a bold move," it is exactly that. It would have been much easier for Nelson to revisit familiar, more fan-friendly territory than to attempt to convey something profound and ineffable while blearily hovering at the edge of perception like a ghost.

This latest full-length from Mark Nelson's long-running and unpredictably shapeshifting project is a collection of understated, near-ambient solo guitar instrumentals that Kranky describes as the culminating release of the composer's "romantic minimalism" side. It certainly is a languorously meditative and unrepentantly lowercase suite of songs, blurring the lines between an "ageless, scarred" Americana and dreamlike ambient drift. Significantly, the album was recorded during the first summer of the pandemic, as Nelson views these songs as a sort of "'lighthouse music,'" radiance cast from a stable vantage point, sending 'a signal to help others through rocks and dangerous currents.'" Given its gently minimal, near-ambient "lone guitar in the fog" aesthetic, The Patience Fader is likely to be something of a polarizing release: it falls dangerously close to calming Windham Hill-style prettiness a couple of times, but it can also feel incredibly poignant and sublime if one chooses to listen deeply enough. While it feels weird to describe music this quiet and slow-moving as "a bold move," it is exactly that. It would have been much easier for Nelson to revisit familiar, more fan-friendly territory than to attempt to convey something profound and ineffable while blearily hovering at the edge of perception like a ghost.

The wintry, desolate, and fog-shrouded view immortalized in the cover art was both a curiously counterintuitive and impressively apt aesthetic choice for a number of reasons. The most immediately striking collision of themes, of course, is that The Patience Fader is a considerably warmer album than the cover art would suggest (and it was recorded during considerably warmer circumstances as well). However, the image does portray a landscape that feels like it is in a lonely state of chilled suspended animation, which nicely mirrors the music in a significant way: all ten of these pieces feel like they exist in a state of bleary and blurred suspension. That is just the backdrop, however, as Nelson's tender melodies metaphorically transform that "before picture" melancholia into something a bit more sundappled and hopeful. Only a bit, mind you, but in a way that definitely matters—like how a break in the clouds on a foreboding day might allow a few rays of light to stream through the window to share their warmth and possibly illuminate floating dust motes in a lovely way.

In less poetic terms, that means that the baseline aesthetic of this album is basically a slow-motion, art-damaged twist on back porch slide guitar blues reverberating through a soft-focus ambient fog. My two favorite pieces are "Harmony Conversion" and "Just a Story," but it is generally true that all of the longer pieces are excellent and that all of the shorter pieces either feel like transitional interludes or like they end too soon to leave a substantial impression. It is also generally true that these songs all feel like variations upon a single elegantly distilled theme, so the ones that boast a distinctive twist understandably tend to be the ones that stand out the most. For example, the opening moments of the far-too-brief "Corniel" feel like a lost great Tim Hecker piece (and a harmonica-driven one at that), while "Harmony Conversion" combines swooning intertwined melodies with some subtle dub touches. "Just a Story," on the other hand, feels like a heavenly collision between Takoma-style Americana and the slow-motion, minimalist psychedelia of Dean McPhee. It also feels like a heavenly collision between the album's rippling, dreamlike production and Nelson's gift for songcraft, as the wistful melody is legitimately gorgeous and a few of the chord changes will likely elicit gasps or chills in those who appreciate such things. That makes it the album's obvious stand-alone highlight, but the vision as a whole is Nelson's more impressive achievement, as he reduced his music to its most nakedly minimal and intimate and did so with nearly unerring execution. This album feels destined to someday be celebrated as a cult/niche masterpiece in lowercase music circles.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

An ear-opening collection of radio broadcasts, live performance recordings, and sketched works in progress from a prolific period in the life of this highly distinctive American composer. In the 1950s, Hovhaness was composing around 12 major works a year, in addition to extensive traveling for research and teaching. He may well have suffered from hypergraphia - an overwhelming urge to be constantly creating - and it is a wonder he found time to be married six times.

An ear-opening collection of radio broadcasts, live performance recordings, and sketched works in progress from a prolific period in the life of this highly distinctive American composer. In the 1950s, Hovhaness was composing around 12 major works a year, in addition to extensive traveling for research and teaching. He may well have suffered from hypergraphia - an overwhelming urge to be constantly creating - and it is a wonder he found time to be married six times.

Born in Somerville, Massachusetts in 1911, to a Scottish mother and Armenian father, Alan Hovhaness had a clear vision and unstoppable determination. From a very young age he loved nature, mountains in particular, and felt the need to compose. Sibelius' 4th symphony was an early inspiration, and Hovhaness' description of the unison melodies in the piece "so lonely and original, [they] said everything there was to say‚ and not only about music" can be applied to many of his own compositions, including on this release. He attended the New England Conservatory at age 22, and actually traveled to Finland in 1935 to forge a friendship with Sibelius. Two years later his 1937 Exile symphony was lauded as the work of a genius by English conductor Leslie Howerd. Yet things did not proceed smoothly: he had four unsuccessful applications for Guggenheim funding, and when he did win a scholarship to Tanglewood, quit after feeling marginalized and humiliated by teachers Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein. The phrase "ghetto music" was allegedly bandied about by Bernstein, who you might think would have been sensitive to such tosh, but it apparently doesn't work that way.

Hovhaness subsequently spent much of the 1940s surviving on meager earnings as organist of the Armenian church in Watertown. At this difficult time he persisted and the universe responded. His spirituality and embrace of his Armenian heritage flourished after guidance from Hermon di Giovanno the Greek painter and mystic, and Armenian colleagues financed and promoted him in both Boston and New York circles. Things turned irrevocably in his favor with a 1944 debut concert of his concerto for piano and strings Lousadzak. In attendance were Lou Harrison and John Cage. Harrison describes the high decibel arguments in the intermission, between attendant Chromaticists and Americanists, both probably aware that they were listening to an original composer who was in neither camp, as "the closest I’ve ever come to one of those renowned artistic riots." He swiftly wrote a rave review and Cage supervised the publication of Mihr (Op.60) for Henry Cowell's New Music series. Cage, of course, is regarded as the doyen of chance operations and aleatory music, and he must have become aware of notations in some of Alan Hovhaness' scores pointing to freedom for musicians to vary the performance. Enthusiastic reviews followed after two brilliant 1947 New York concerts, and then, in October 1955, Leopold Stokowski's use of Hovhaness' Mystical Mountain for his debut with the Houston Symphony made sure the critical tides stayed turned in favor of the composer.

Hovhaness does not appear to have harbored any grudges, nor lost his humility. If he felt persecuted by anything it was by the need to write down the compositions surging through his head. There is a story of him being taken to hear a Thelonious Monk concert and spending much of the post-gig social time swaying to the music he still heard and furiously writing down all the notes he recalled Monk playing. In any event, Opening a Window to Cosmic Love is a marvelous collection from a pivotal time in the composer’s career. Several pieces are from a commission for television called Assignment India and others from Arjuna, which was also the first Western music ever performed at the Madras Music Festival in India on New Years Day, 1960. What emerges from listening to this Hovhaness collection is the strong sense that did not merely borrow influences (he never steals a folk tune wholesale) from other cultures and locations (Russia, Korea, Japan, Hawaii, Honolulu, or wherever) to spice up his own creativity. Instead he incorporates them in his compositional thinking in a way which transcends both geography and time. There are also hints here of the more expansive compositions (which money allowed him to create) and the deliberate romanticism which dominated his work from the 1970s until his death. The spiritual purity and simple melodic beauty of these delightfully unpredictable and complex works is undimmed after three quarters of a century. Hovhaness achieved his vision "to create music not for snobs but for all people, music which is beautiful and healing, to attempt what old Chinese painters called 'spirit resonance" in melody and sound."

Read More

- Eve McGivern

- Albums and Singles

Over a series of acid-fueled all-night jam parties at Dierks Studio in 1973, Die Kosmischen Kuriere ("Cosmic Couriers") label musicians Klaus Schulze (Tangerine Dream), Harald Grosskopf and Jürgen Dollase (both of Wallenstein), Manuel Göttsching (Ash Ra Tempel), and Dieter Dierks assembled. The result spawned a cosmic barrage of stream-of-consciousness experimentation with immersive sound loops and kinetic rhythms, awash in interstellar guitar sorcery and sound effects. Unbeknownst to the musicians involved, this magic was captured on tape by label head Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser and Gille Lettmann. When a mysterious group called The Cosmic Jokers appeared on the label the following year, the affected musicians took legal action, dissolving the contracts effectively ending the label. Thankfully, the magic was committed to immortality and now exists in its space rock glory. With original vinyl pressings going for hundreds of dollars, this latest reissue -- fully licensed and remastered from the original analog master tapes at the original recording studio -- puts this essential listening in the hands of more listeners.

Over a series of acid-fueled all-night jam parties at Dierks Studio in 1973, Die Kosmischen Kuriere ("Cosmic Couriers") label musicians Klaus Schulze (Tangerine Dream), Harald Grosskopf and Jürgen Dollase (both of Wallenstein), Manuel Göttsching (Ash Ra Tempel), and Dieter Dierks assembled. The result spawned a cosmic barrage of stream-of-consciousness experimentation with immersive sound loops and kinetic rhythms, awash in interstellar guitar sorcery and sound effects. Unbeknownst to the musicians involved, this magic was captured on tape by label head Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser and Gille Lettmann. When a mysterious group called The Cosmic Jokers appeared on the label the following year, the affected musicians took legal action, dissolving the contracts effectively ending the label. Thankfully, the magic was committed to immortality and now exists in its space rock glory. With original vinyl pressings going for hundreds of dollars, this latest reissue -- fully licensed and remastered from the original analog master tapes at the original recording studio -- puts this essential listening in the hands of more listeners.

The 48-year-old master tapes remained in excellent condition. With Dieter Dierks himself collaborating, this latest edition truly benefits from modern technology with a marked improvement over bootleg copies and original pressings. Despite being shunned by the original musicians, the music solidly stands as a prime example of the height of freeform creativity without limits, freedom of exploration at the hands of already skilled musicians. Göttsching, influenced by the free jazz movement and already breaking new exploratory ground on electric guitar in Ash Ra Tempel, joins his musical partner Klaus Schulze, fresh from Tempel and Tangerine Dream. Grosskopf had previously partnered with them for Walter Wegmüller's 1973 Tarot, the project initiated by Timothy Leary, who had partnered with Tempel on 1973's Seven Up. Göttsching, Schulze, and Groskopf form a key trio. Göttsching's improvisational guitar work remains central to the album, bearing more than a passing resemblance to Tempel but flowing with, around, and over Schulze's droning organ, with Groskopf exhibiting his practice hand on drums, each embracing their part with controlled abandon within a larger whole. Dollase lends beautiful keyboard work with piano, Farfisa, and mellotron, while Dierks' often dark and ominous bass playing lends just enough rhythmic grounding for music that continuously takes flight.

After years of sub-par reissues, it's terrific to have such a quality release of this cerebral music, not to mention one more easily obtained. Crisply defined drum strokes, rich guitar acoustics, and distinctly audible electronic effects make this a joy to revisit, with the overall sound unmuddied and flawless.

Samples can be found here and here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

It is not quite accurate to say that Saint Abdullah completely reinvent their sound with each new album, but is fair to say that Mehdi and Mohammad Mehrabani-Yeganeh are far more interested to exploring meaningful new territory than with building upon their past successes. While that is certainly an admirable trait, it can also be a frustrating one, as I know Saint Abdullah will probably never fully return to the more industrial-indebted aesthetic of their earlier albums (which I love). On the bright side, that also means that every new Saint Abdullah album has the potential to blindside me with a bold leap forward into previously uncharted creative territory. In that regard, Inshallahlaland falls a bit short of being a particularly revelatory album as a whole, yet it does explore some characteristically intriguing and thoughtful themes and features quite a fascinating longform piece ("Glamour Factory"). For me, the appeal of Inshallahlaland begins and ends there, but that one excellent 20-minute sound collage is enough to make the album a significant release that fans will not want to pass over.

It is not quite accurate to say that Saint Abdullah completely reinvent their sound with each new album, but is fair to say that Mehdi and Mohammad Mehrabani-Yeganeh are far more interested to exploring meaningful new territory than with building upon their past successes. While that is certainly an admirable trait, it can also be a frustrating one, as I know Saint Abdullah will probably never fully return to the more industrial-indebted aesthetic of their earlier albums (which I love). On the bright side, that also means that every new Saint Abdullah album has the potential to blindside me with a bold leap forward into previously uncharted creative territory. In that regard, Inshallahlaland falls a bit short of being a particularly revelatory album as a whole, yet it does explore some characteristically intriguing and thoughtful themes and features quite a fascinating longform piece ("Glamour Factory"). For me, the appeal of Inshallahlaland begins and ends there, but that one excellent 20-minute sound collage is enough to make the album a significant release that fans will not want to pass over.

According to the Iranian-raised Mehrabani-Yeganeh brothers, the central themes of their latest release are: 1) how society is less-than-accepting of people with multiple identities, and 2) how we connect with human voices on a uniquely deep level (even when they appear in sampled and deconstructed form).  Both themes are particularly prominent in the opening "Glamour Factory," which borrows part of a speech by "one of Iran's pre-eminent film voiceover artists" about how working in film allowed him to break free of society's deeply ingrained identity prejudices to some degree. Unsurprisingly, that sentiment resonated deeply with the brothers, as they are attempting to achieve a similar liberation through their own work. Also, they drolly note that it "felt fitting to sample the ultimate sampler." That speech proves to merely be a starting point, however, as "Glamour Factory" mostly makes me feel like I am channel surfing Iranian TV on hallucinogens, as it is freewheeling, psychotropic swirl of sampled voices, looped fragments of songs, and street noise that fitfully plunges into passages of wild manipulations, distortions, and stammering edits. In fact, it almost feels like someone pressed a collection of television snippets to vinyl, then handed it off to a avant-garde-minded turntablist for the full chopped and screwed treatment, though there are also some beautifully minimal or melodic passages thrown into the mix too (as well as some flashes of dark humor celebrating "the benefits of mechanized civilization"). If "Glamour Factory" had been stretched out to consume the entire album, I would probably proclaim Inshallahlaland to be an unambiguous triumph, but it is instead rounded out by three shorter pieces of varying quality. My favorite of the lot is "Blurring Of Management Theory," which deftly combines a shivering and shimmering melodic theme with an endlessly shifting backdrop of clicks, pops, squelches, and subdued rumble. It is admittedly more of a snack than a meal though and I remain perplexed by the brothers' love of bloopy synth improvisations exhibited on the other pieces. That said, the successes of Saint Abdullah continue to delight me even if their hit-to-miss ratio is less than ideal, as this project is an endearingly personal, unpredictable, and playfully outré one quite unlike anything else.

sounds can be found here

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This Krakow-based composer's debut album was one of 2021's most pleasant late-year surprises, as Making Eye Contact With Solitude is a gorgeously warm and intimate gem of multilayered and masterfully textured psychedelia. Basta describes the album as a diaristic meditation on "domesticity, loneliness, repetitiveness, stubborn patterns of isolated minds and the sonic mysteries all around us" and cites the murderers' row of Cucina Povera, Félicia Atkinson, and claire rousay as key inspirations. While welcome shades of all three artists are certainly evident to some degree on these six songs, Basta's aesthetic already feels fully formed and distinctively her own. In fact, I suspect it will not be long at all before Basta regularly finds herself name-checked as an inspiration by other artists, as her unhurried and dreamlike phantasmagoria of rippling zithers, vividly textured field recordings, and enigmatic domestic sounds feels absolutely revelatory on the album's two strongest pieces.

This Krakow-based composer's debut album was one of 2021's most pleasant late-year surprises, as Making Eye Contact With Solitude is a gorgeously warm and intimate gem of multilayered and masterfully textured psychedelia. Basta describes the album as a diaristic meditation on "domesticity, loneliness, repetitiveness, stubborn patterns of isolated minds and the sonic mysteries all around us" and cites the murderers' row of Cucina Povera, Félicia Atkinson, and claire rousay as key inspirations. While welcome shades of all three artists are certainly evident to some degree on these six songs, Basta's aesthetic already feels fully formed and distinctively her own. In fact, I suspect it will not be long at all before Basta regularly finds herself name-checked as an inspiration by other artists, as her unhurried and dreamlike phantasmagoria of rippling zithers, vividly textured field recordings, and enigmatic domestic sounds feels absolutely revelatory on the album's two strongest pieces.

The album is comprised of six songs that seamlessly segue into one another, so it was presumably intended as a single longform work. The pieces certainly flow together nicely and share many of the same elements, but a couple of pieces make enough of an impression to easily stand alone. Whether or not the opening "Awakening" falls into that category is currently the subject of some internal debate on my part, but I certainly like it a lot regardless of where it ultimately lands. I am tempted to glibly summarize it as "someone is murdering a saxophone in the nightmare forest," yet it is far too lovely to deserve such a fate. Instrumentally, it is centered upon a blearily twinkling zither motif, yet the smeared and flutteriing psychotropic sounds and crunching footsteps that emerge from that modest theme soon consume the piece and completely steal the show. As with most pieces on the album, the magic lies primarily in the execution, as Basta is remarkably skilled at crafting wonderfully layered and kinetic soundscapes from her field and household recordings.

The following "Memories of Unwanted" is a considerably more emphatic album highlight, as "Awakening" beautifully morphs into warmly shimmering ambiance enhanced with a host of vividly crackling and sizzling textures before unexpectedly blossoming into a hallucinatory crescendo of murmuring, cooing, and gibbering voices. It calls to mind a flock of psychedelic pigeons crashing one of the more meditative passages on a Tim Hecker album, which is no simple feat. It also kicks off a three-song run of sublime near-perfection, as both "Unknown Reel Tape" and "Walking Around In Circles" are similarly stellar. "Unknown Reel Tape" resembles a killer duet between a warbling, warped, and possibly reversed Dead Can Dance cassette (the murky vocals are very Gerrard-esque) and bunch of clinking glass bottles and other curious sounds, while the dreamy, mantric vocal swoons of "Walking Around in Circles" call to mind an especially strong Cucina Povera song. That would admittedly be a fine stopping point, yet it proves to be only the starting point for a gloriously vivid crescendo that evokes a dreamily reverberating, slow motion rain of crystals. On that piece in particular, Basta's textural wizardry with non-musical sounds is truly on a level that I do not often encounter, as she manages to make familiar sounds feel almost enchanted due to their sheer clarity and physicality. It favorably calls to mind some of Graham Lambkin's singular work, as he seems like the sort of artist who could convincingly make a satisfying album from little more than a shoe and microphone. I get a very similar feeling from Basta, as I would probably still love this album even if all the instruments suddenly vanished to leave behind only clinking glass, clanking metal, crashing waves, and a host of enigmatic crunches and crackles.

sounds can be found here

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest release from Mogard is something of a modest one, as he describes it as "the result of experimentation with familiar and less familiar instruments available to me in the studio between 2019 and 2022." No further information is divulged about the album's "less familiar" elements aside from an interesting mention of reverb borrowed from the Inchindown oil tanks, which apparently hold the world record for longest reverberation time. If In a Few Places Along the River were a Lea Bertucci or Pauline Oliveros album, that expansive reverb would no doubt be a defining feature, but it seems like Mogard harnessed it in an more unusual and inventive way. The results are admittedly not quite top-tier Mogard (this is a digital-only release, after all), as this album captures him in stark, slow-burning drone mode rather than one of his more melodic and warm moods, but it is still solid enough to be satisfying, as the two bookends are impressively nuanced and substantial.

This latest release from Mogard is something of a modest one, as he describes it as "the result of experimentation with familiar and less familiar instruments available to me in the studio between 2019 and 2022." No further information is divulged about the album's "less familiar" elements aside from an interesting mention of reverb borrowed from the Inchindown oil tanks, which apparently hold the world record for longest reverberation time. If In a Few Places Along the River were a Lea Bertucci or Pauline Oliveros album, that expansive reverb would no doubt be a defining feature, but it seems like Mogard harnessed it in an more unusual and inventive way. The results are admittedly not quite top-tier Mogard (this is a digital-only release, after all), as this album captures him in stark, slow-burning drone mode rather than one of his more melodic and warm moods, but it is still solid enough to be satisfying, as the two bookends are impressively nuanced and substantial.

Mogard was definitely not in a hurry to make to make an impression with this album, as the opening "Against a White Cloud" fades win with blearily smeared drones that evoke the unsettling nocturnal ambiance of David Lynch at his most darkly atmospheric. Gradually, however, it starts to blossom into something less drifting and ghostly, which is a transformation that I suspect is indebted to the oil tank-inspired reverb. At the very least, it feels like a feedback loop of some kind, as each layer of drone added lingers around to provide a frayed and dissolving backdrop for the next. In any case, it is an impressively likable and stealthily heavy piece, gradually snowballing into a smoldering and snarling roar of tightly reined elemental power. The following "In True Contemplation" takes a similar route, as it begins with a quiet, barely perceptible synth drone and steadily intensifies into an engulfing roar. It feels a bit colder and more minimal than its predecessor, which makes it less memorable, but the insistent and rhythmic bass throb is a nice enhancement. The album's entire second half is then devoted to the 21-minute epic "Along The River," which can reasonably be described as both a variation of the same themes as the earlier pieces and the strongest single iteration of those themes. That success is mostly because it has more of a melodic component than the other pieces, but it is also more fluid, tender, twisting, and subtly spacy. Moreoever, the steadily intensifying arc of the piece ultimately ebbs back towards silence, which gives the piece the feel of a lunar eclipse slowing blotting out the sun, then slowly revealing its warmth and light once again. Not that much warmth and light, mind you, as the piece has the ineffable sadness of an elegy, but it feels movingly transcendent as well. A sublime 21-minute highlight is more than enough to carry the album for me, but Mogard fans less enthusiastic about his cold, minimal, and unhurried drone side should proceed with caution. Serious drone connoisseurs will find much to love here, however, as In a Few Places Along the River captures a master allowing himself plenty of room to fully indulge his gifts for elegantly controlled, slow-burning magic.

sounds can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I was not expecting 2014's odds n' ends collection Fight for Your Dinner to ever have a sequel, so this latest batch of eclectic covers, one-off experiments, unusual collaborations, and orphaned songs came as a very pleasant New Year's Eve surprise last December. While the covers are a bit less leftfield this time around (no Missy Elliott), they compensate by being even better, as the duo's sublime interpretation of two '80s Prince classics is one of the best goddamn things that they have ever recorded. The album also features one hell of an excellent tribute to the late Jack Rose, reworkings of songs by Pixies and Amon Düül II, a homemade electronics experiment, and a six-year-old's bold vision for the perfect pop song. Given the album's freewheeling randomness and the focus upon previously unreleased pieces, one could be forgiven for thinking that Fight For Your Dinner II is strictly one for the band's most devout fans, but it is extremely rare for Big Blood to release anything that does not feature at least one absolutely essential song and this one has several (as well as some great cover art). Of course, I am admittedly speaking as one of the aforementioned "most devout fans," but I still believe it is an objective fact that there is an impressive amount of revelatory material here. And that anyone left cold by the "When Doves Cry/I Would Die For You" cover should be extremely concerned that their ears may be broken.

I was not expecting 2014's odds n' ends collection Fight for Your Dinner to ever have a sequel, so this latest batch of eclectic covers, one-off experiments, unusual collaborations, and orphaned songs came as a very pleasant New Year's Eve surprise last December. While the covers are a bit less leftfield this time around (no Missy Elliott), they compensate by being even better, as the duo's sublime interpretation of two '80s Prince classics is one of the best goddamn things that they have ever recorded. The album also features one hell of an excellent tribute to the late Jack Rose, reworkings of songs by Pixies and Amon Düül II, a homemade electronics experiment, and a six-year-old's bold vision for the perfect pop song. Given the album's freewheeling randomness and the focus upon previously unreleased pieces, one could be forgiven for thinking that Fight For Your Dinner II is strictly one for the band's most devout fans, but it is extremely rare for Big Blood to release anything that does not feature at least one absolutely essential song and this one has several (as well as some great cover art). Of course, I am admittedly speaking as one of the aforementioned "most devout fans," but I still believe it is an objective fact that there is an impressive amount of revelatory material here. And that anyone left cold by the "When Doves Cry/I Would Die For You" cover should be extremely concerned that their ears may be broken.

The album kicks off in somewhat modest fashion with a couple of previously released rarities from the project's substantial discography: the stomping "Half Light Blues" (from a 7” split lathe with Human Adult Band) and the lurching electronic weirdness of "Floating from Xanthi," which was originally issued with a Greek fanzine (LUNG). That second piece is an interesting one, as it originates from a planned/unfinished album of works made using homemade electronics and calls to mind a spirited Big Blood/Silver Apples mash-up. For the most part, however, most of the strongest songs on this collection are covers, which is a bit of a surprise, given how much I love generally Colleen Kinsella and Caleb Mulkerin's songwriting. The pair do knock it out of the park with one original piece though, as "The Fox and The Rose" beautifully memorizes Jack Rose and a hapless fox with a classic Fire on Fire-style feast of vocal harmonies, fingerpicked acoustic guitars, backwards melodies, and psych-damaged guitar noise. I am frankly surprised it managed to elude release until now, as it feels like an instant stone-cold classic in the Big Blood canon. I am less bowled over by the Amon Düül II cover that follows, as the duo excised one of the best parts of the song (the drums) in favor of a straightforward chug, but I may be in minority on that, as I have seen more than one person proclaim it to be the single best song on the album. Unfortunately, that honor was already decisively claimed by the sensuous drone-trance shimmer of the double Prince cover (recorded the night the duo learned of his death, no less). Transforming an unimprovable/brilliant/perfect song ("When Doves Cry") into a completely different great song is quite an impressive feat, yet Big Blood work a different kind of killer alchemy with Pixies' "Velouria," transforming a song I basically remembered only as a pleasantly catchy single into a beautifully frayed, intimate, and poignant piano ballad. By my count, that adds up to three top-tier Big Blood songs buried in a ten-song collection of ostensible vault scrapings, but the album has one more big surprise to offer as well, as it closes with a young Quinnisa's breathless foray into home-recorded autotune disco ("she insisted that I make her sound like the 'robots' she heard on the radio").

sounds can be found here

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This latest double album from the California-based Fritch is something of a culmination of two separate long journeys, as it took eight misfortune-filled years to complete and it also concludes Lost Tribe's "Built Upon a Fearful Void" series. While I am not necessarily sure that Fritch himself would agree that the end result was worth suffering through the gauntlet of lost hard drives and water-damaged tape reels that he had to navigate to get to this point, Built Upon a Fearful Void nevertheless meets my dauntingly high expectations for any major new statement from the composer. That said, I am certainly curious about how much the album changed between the ruined tape reels and Fritch's decision to abandon "what remained of the salvaged material" and "rerecord the album entirely using only faint flickers of the old tapes and cassettes." On one hand, some magic simply cannot be recaptured, yet that loss is balanced by the fact that Fritch's work seems to only get better and better with each passing year. In any case, anyone who fell in love with Fritch's work from 2019's Deceptive Cadence will likely love this album too (particularly its first half), as Built Upon a Fearful Void is another impossibly rich and vivid plunge into a dreamlike and cinematic vision of bittersweet Americana (and some other very likable other things as well).

This latest double album from the California-based Fritch is something of a culmination of two separate long journeys, as it took eight misfortune-filled years to complete and it also concludes Lost Tribe's "Built Upon a Fearful Void" series. While I am not necessarily sure that Fritch himself would agree that the end result was worth suffering through the gauntlet of lost hard drives and water-damaged tape reels that he had to navigate to get to this point, Built Upon a Fearful Void nevertheless meets my dauntingly high expectations for any major new statement from the composer. That said, I am certainly curious about how much the album changed between the ruined tape reels and Fritch's decision to abandon "what remained of the salvaged material" and "rerecord the album entirely using only faint flickers of the old tapes and cassettes." On one hand, some magic simply cannot be recaptured, yet that loss is balanced by the fact that Fritch's work seems to only get better and better with each passing year. In any case, anyone who fell in love with Fritch's work from 2019's Deceptive Cadence will likely love this album too (particularly its first half), as Built Upon a Fearful Void is another impossibly rich and vivid plunge into a dreamlike and cinematic vision of bittersweet Americana (and some other very likable other things as well).

According to Fritch, Built Upon a Fearful Void is intended as "a two-part record—meditating on lost epochs, feeble mythologies, and the many deep gulfs in human knowledge and perception," which are certainly themes that resonate more than I would like right now. While I am not sure how the shifting vistas of each individual disc are intended to explore the different conceptual themes, it is quite clear that each disc works as a self-contained album with its own thoughtful and satisfying dynamic arc. While the same instrumental palette ("pipe organ, reed instruments, voice, viola da gamba, prepared piano, pedal steel, viola d’amore, and banjo") remains roughly intact for both of the album's halves, the emphasis shifts emphatically towards more drone-inspired pipe organ meditations for the second disc. In broad terms, that means that the more orchestral first disc is a closer relative to Deceptive Cadence than the second one, as Fritch's gorgeous string melodies are the heart of everything (along with his longstanding passion for vividly realized textures, of course). On the strongest pieces, Fritch's ear for poignant melodies strikes a perfect balance with tactile physicality, elevating such pieces into something a bit more unique and transcendent. Of course, business-as-usual Fritch remains perfectly fine by me as well, even if the thrill of discovery has dulled from my reasonable familiarity with his voluminous discography and its various phases. Still, the bookends on the first disc both handily attain some degree of transcendence for me (particularly the closing "Truest of Truisms"), as Fritch tends to go big with his opening and closing numbers. However, some of the album's most sublime highlights fall between those two crescendos too. For example, "Canary" beautifully marries a lovely viola melody with frayed and haunted-sounding feedback and a viscerally crunching and clanging backdrop of unconventional percussion. Elsewhere, the heaving and rippling "Glossolalia" is a tour de force of spectral, ravaged melodies and churning elemental power. That said, "Truest of Truisms" definitely ends the first disc with one hell of an exclamation point, unfolding as an organically heaving dream of widescreen romanticism, crashing cymbals, and elegantly dancing melodies.

The second disc opens in far more subdued fashion, as the aptly named "Low Smoulder" transforms languorous, sacred-sounding organ drones into a slow-building swell of escalating intensity.Mood-wise, that piece makes for quite a representative introduction to the darker, more minimal second half, which feels a lot like a classical requiem that is either slowly burning up or veiled by supernatural fog.As with the first disc, the second disc too culminates in one of the album's most ambitious and strikingly beautiful pieces.In fact, "A Wilderness to Be Suffered" may damn well be the strongest single piece on the album, as it feels like a slow motion organ mass with the melody loosely doubled by languorous swells of bowed viola da gamba.The actual piece is far more complex and beautiful than that description suggests, however, as the piece seems to blearily twist and wind around itself like curling tendrils of smoke.Elsewhere, "The Shallow Veil" visits similar territory, but the organ theme seems to dissolve into a fog to bring the tender heartache of the viola da gamba melody into stark relief.There are also some nice tape or string noise textures that periodically materialize in the haze, which I wholeheartedly welcome."Critical Mass" heads in a more fluttering and flickering drone-inspired direction, but ultimately arrives at a similarly satisfying balance of hallucinatory, soft-focus sounds and sharper, more anguished-sounding textures.Other highlights include the blearily lovely pipe organ reverie "Untimely," which slowly blossoms into dynamically rich layers of shivering, rattling, and frayed beauty, and the slow-burning one-two punch of "Capacitance" and "Lay Hands Upon Us."I especially love the sounds in the latter, as it almost sounds like a shoegaze-damaged singing saw performance.There are a few other pieces like "The Cooling Board" that deserve mention as well, but it would be fair to describe Built Upon a Fearful Void's second disc as "variations on a theme."Describing the actual theme being varied is bit more challenging, but I am going with "hypnagogic organ mass/heavy-hearted requiem for humanity enhanced with an inventive array of gnarled and gnawed textures."Of the album’s two halves, I currently prefer the more melodic and percussion-enhanced first half, but the whole album is basically a world-building opus in a vein that is all Fritch's own: the sweeping grandeur of the best soundtrack composers colliding with a talented sound designer and a producer with a real knack for subtly smeared and psychotropic textures.Finding all of those facets properly balanced on the same album is rare enough, but encountering them all in the same person feels like stumbling upon a goddamn unicorn in the wild.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

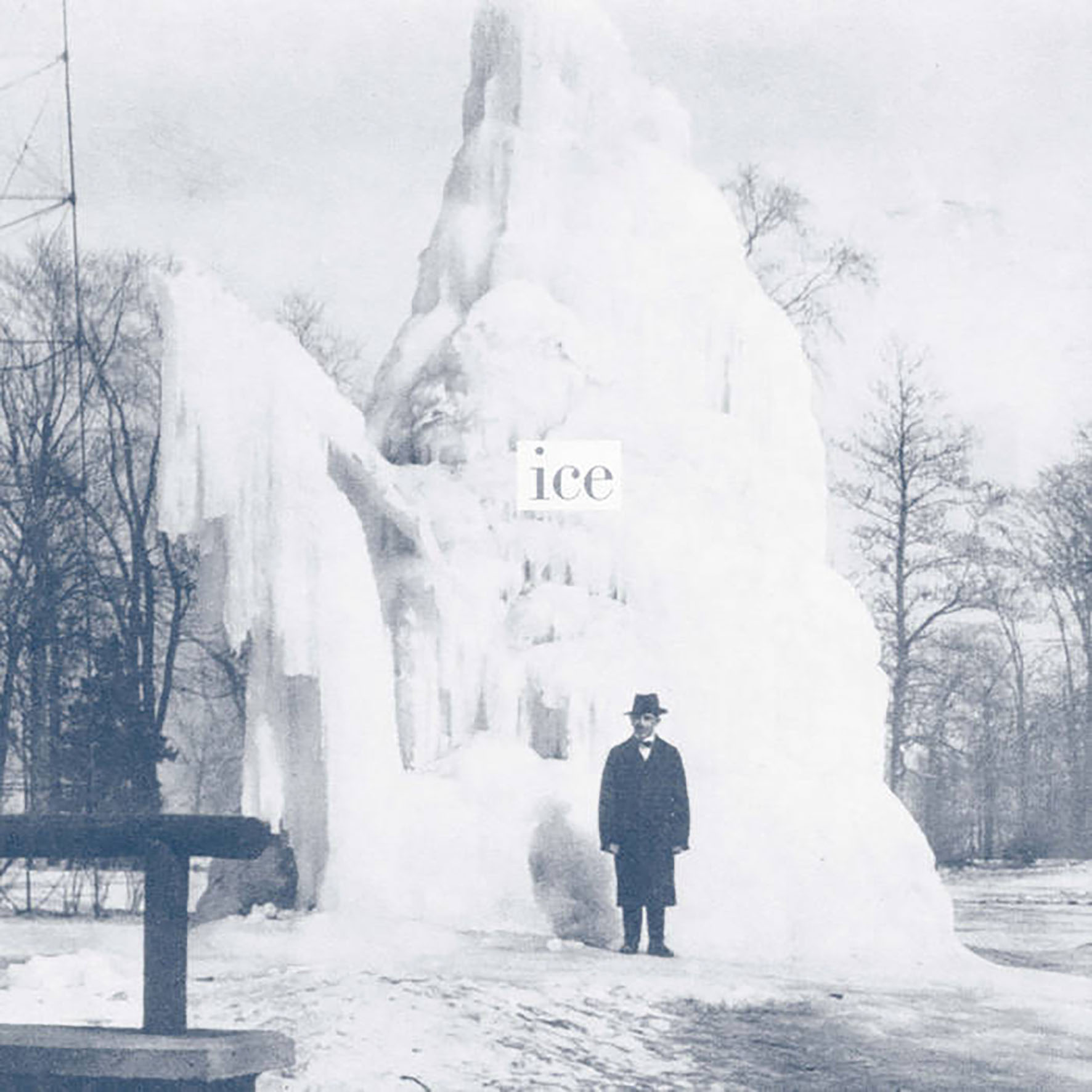

Back in 2008, Steve Roden quietly released one of my favorite ambient albums of all time in a signed limited edition of 250. Of course, I did not realize it at the time, so it took another decade or so before Stars of Ice finally made its way to my ears. Happily, however, Room40 has now reissued Roden's hauntingly beautiful collage of obscure and antique Christmas records, which will hopefully nudge many more receptive ears towards this modest, one-of-a-kind masterpiece. While I am sure I would have greatly enjoyed the original album if I had heard it when it was first released, it is worth noting that my appreciation for texture has evolved considerably over the years, so maybe Stars of Ice uncannily got to me at precisely the right time. In fact, I wonder how significant a role Roden himself has (indirectly) played in my shifting tastes, as he has always been ahead of his time in regard to celebrating details and nuances (as well as inventively repurposing "non-musical" sounds) and we seem to be in the midst of a textural renaissance at the moment. That said, most of Stars of Ice is as nakedly beautiful as music can get, so the quavering murkiness, crackling and popping vinyl, and pleasantly lapping waves of hiss are mere icing on an already gorgeous cake. This is an absolutely brilliant and magical album.

Back in 2008, Steve Roden quietly released one of my favorite ambient albums of all time in a signed limited edition of 250. Of course, I did not realize it at the time, so it took another decade or so before Stars of Ice finally made its way to my ears. Happily, however, Room40 has now reissued Roden's hauntingly beautiful collage of obscure and antique Christmas records, which will hopefully nudge many more receptive ears towards this modest, one-of-a-kind masterpiece. While I am sure I would have greatly enjoyed the original album if I had heard it when it was first released, it is worth noting that my appreciation for texture has evolved considerably over the years, so maybe Stars of Ice uncannily got to me at precisely the right time. In fact, I wonder how significant a role Roden himself has (indirectly) played in my shifting tastes, as he has always been ahead of his time in regard to celebrating details and nuances (as well as inventively repurposing "non-musical" sounds) and we seem to be in the midst of a textural renaissance at the moment. That said, most of Stars of Ice is as nakedly beautiful as music can get, so the quavering murkiness, crackling and popping vinyl, and pleasantly lapping waves of hiss are mere icing on an already gorgeous cake. This is an absolutely brilliant and magical album.

Room40/New Plastic Music

The album takes its name from a Chinese Christmas carol record that was one of the eclectic pair of pieces that Roden salvaged for his primarily sound sources. The other lucky winner was a song entitled "Snow" from a clearly hit-packed 78 entitled "Songs From the First Grade Reader." Unsurprisingly, I suspect both pieces would be nearly unrecognizable to their original composers in the wake of Roden's radical deconstructions, yet this is not one those albums where the character of the original pieces is completely obliterated into noisy abstraction, as Stars of Ice is an unusually melodic entry in the composer's oft-challenging oeuvre. There were apparently also "various other objects and instruments" involved as well, but they never manifest themselves in recognizable ways, as the heart of Stars of Ice is essentially just snatches of vocal melodies and a crackling and hissing backdrop of pleasantly warm and murky organ chords (or at least something that sounds like an organ after Roden was finished with it). For a while, the piece feels like it is just going to linger in suspended animation forever, which would be apt given the "enchanted snow globe/slowly dissolving into the grooves of a wobbly old record" atmosphere, yet new threads (clipped vocal melodies, plinking and shivering strings, a choir, and a colorful host of coos, mumbles, and warbles) soon appear and begin weaving together in interesting and lovely ways. For the piece's first half, the warm chords, bittersweet central melody, and the flickering and ghostly choral snippets conjure one of the most sustained stretches of sublime, pure beauty that I have yet heard. The piece never stops glacially and subtly transforming, however, so that section is just one particularly exquisite phase of an immersive and hallucinatory journey towards a final stretch that approximates a haunted music box haltingly playing a fragmented, wrong speed recording of a rural Chinese or Eastern European traditional music ensemble. Admittedly, I likely would have been perfectly happy if Roden had just lingered in the most beautiful stretch forever, but the subtly intensifying shadows and sense of mystery that follow are what elevate Stars of Ice to something deeper and more complex than merely a masterfully executed collage of lovely sounds. In that regard, the album is characteristically stellar sound art, but Roden's larger achievement is how masterfully he managed to convey ineffable feelings of beauty, sadness, and longing from just a couple of children’s records that no one has presumably thought about in half a century.

Samples can be found here.

Read More