- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

The title of the latest Novi_sad work roughly translates to lightning or thunder as related to Zeus and is a wonderfully fitting title for this album. Based on environmental sounds recorded on five different continents, Thanasis Kaproulias’s latest album is neither pure field recordings, nor is it the product of laborious processing and treatments. Instead it sits nestled somewhere between the two: some segments are clearly recordings of rainstorms or birds, but others are shaped into blasts of noise or melody, sometimes within the span of a few minutes, conjuring beauty and fear much in the way a thunderstorm does.

The title of the latest Novi_sad work roughly translates to lightning or thunder as related to Zeus and is a wonderfully fitting title for this album. Based on environmental sounds recorded on five different continents, Thanasis Kaproulias’s latest album is neither pure field recordings, nor is it the product of laborious processing and treatments. Instead it sits nestled somewhere between the two: some segments are clearly recordings of rainstorms or birds, but others are shaped into blasts of noise or melody, sometimes within the span of a few minutes, conjuring beauty and fear much in the way a thunderstorm does.

Right from the opening piece, "Oceania," this dynamic is apparent. Based on recordings taken at the Tarkine Rainforest, Kaproulias leads off with an electronic-tinged swarming sound, resembling processed migrating birds, and a passing rainstorm. Without warning it blasts into a wall of harsh noise, yet there is still the depth and complexity of sounds amidst the harshness. Slowly he transitions from the noise to focus on a melody that slowly drifts in, ending on quite a beautiful note. The harshest moments of ΚΕΡΑΥΝΟΣ lie in "Oceania," while both "Asia" and "Europe" are built from similar components: bass heavy rumbles, water sounds, and far off droning melody. The former features a bit more melodicism overall, wobbling and lying under strange textures, while the latter allows more of the unprocessed natural recordings to shine through.

Throughout "Africa," Kaproulias opts for an almost more traditionally musical dynamic. Insect recordings are reassembled into something resembling bowed strings, and whole thing has an almost rhythmic structure due to his use of looping. The ending is a bit more pure melody and chiming tones, but there is a path of overdriven, harsher sounds on the way there. "America," based on Amazon Rainforest and recordings of Niagara Falls is overall more dense and oppressive in its dynamic. The combination of rain and waterfall recordings is heavy and enveloping, and the aggressive water sounds only relent at the very end, leaving a foundation of dark, muted tones.

Kaproulias may work with a similar approach and dynamic on the five pieces that make up ΚΕΡΑΥΝΟΣ, but each clearly has its own overall feel and identity. His subtle approach to processing and production is a significant asset here, as it so effortlessly blurs the line between source material and processed results, making for a work that is as much field recording as it is musical. Beautiful, harsh, and jarring from beginning to end, the title fits the work perfectly.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

Initially intended to be a lockdown project based around recycling (and re-recycling) of sound sources, Stephen Meixner (Contrastate) ended up shifting the theme of A Silent War to a very specific one. Based on the worldwide ripples of the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer gave a specific theme to an otherwise conceptually defined record. Featuring contributions by the other members of Contrastate, Ralf Wehowsky, Steve Pittis (Band of Pain) and more, the final product is as enthralling as it is bleak and depressing.

Initially intended to be a lockdown project based around recycling (and re-recycling) of sound sources, Stephen Meixner (Contrastate) ended up shifting the theme of A Silent War to a very specific one. Based on the worldwide ripples of the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer gave a specific theme to an otherwise conceptually defined record. Featuring contributions by the other members of Contrastate, Ralf Wehowsky, Steve Pittis (Band of Pain) and more, the final product is as enthralling as it is bleak and depressing.

Black Rose Recordings/Oxidation

The opening title piece, featuring sound sources from Rob Fairweather, has a bent music box quality to it, over which the names of victims of unjustified police shootings (Walter Scott, Tamir Rice) are read. With a strange percussion loop anchoring the song, what almost resembles 1970s cop TV show soundtracks are weaved in and out. The gurgling electronics of "Breathe" take on a disturbing color as George Floyd’s last words are spoken, with bits of rhythm popping up throughout. The lush, beautiful electronics are a stark contrast to the otherwise bleakness of the recording.

Both "Virtue Signaling" and "Unfinished Business" are a bit less depressive, with the former having a more traditional synth-based sound within a mass of piano hits and sampled music, with both featuring percussion by Simon Wray and raw materials by Ralf Wehowsky. The latter is overall more spacious, driving by a bassy electronic pulse, although the far off police sirens are appropriately disturbing even at low volumes. "We Demand Tomorrow (Or Business as Usual)" casts droning electronics alongside Wray's unconventional percussion, with buzzing, dense blasts of sound symbolically interrupting the status quo. Closer "Singing About Revolution" features Contrastate member Jonathan Grieve using the words of Nina Simone lyrics, bent and processed within a mix of swirling electronics, feedback, and fragmented sampling. The sum of the parts make for a disturbing, unsettling sound throughout.

As captivating as it is, A Silent War is an ugly, unpleasant record, which was surely Meixner's intent. A strange mélange of existing sounds, absurd attempts at traditional musicality, and heavy subject matter, it certainly is not the type of album that screams for casual listening. This prevailing sense of unease though leads to a thematically unified album that captures the ugliness of 2020 and 2021 very well, and sadly 2022 is not looking to be too different. At least it might result in another fascinating work from Meixner, however.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I am thrilled that Room40 is digging up and reissuing some woefully underheard gems from Steve Roden these days, as a hell of a lot of fascinating work passed me by in the pre-Bandcamp days of hyper-limited physical releases. Stars of Ice (due for a reissue in February) was especially revelatory for me, but this more modest initial dispatch from Roden's vaults is quite a treat as well. As far as I know, Oionos has not been released previously, yet it dates from a 2006 exhibition in Athens, Greece entitled The Grand Promenade. The premise of the exhibition was to create a "dialogue" between "contemporary site-specific works" and "various archaeological and historical sites in central Athens," but Roden fell in love with the Church of St. Dimitris Loumbardiardis (not among the planned sites) and managed to talk the curator into allowing an exception. Notably, the architect behind the church was the same man (Dimitris Pikionis) who designed the original promenade, so Roden's selection was a thoughtful and inspired decision, as he felt the path leading to the church provided a "stronger impression of Pikionis's vision" than the actual promenade (unlike the main promenade, the path to the church escaped being ‘restored’ in preparation for the 2004 Olympics).

I am thrilled that Room40 is digging up and reissuing some woefully underheard gems from Steve Roden these days, as a hell of a lot of fascinating work passed me by in the pre-Bandcamp days of hyper-limited physical releases. Stars of Ice (due for a reissue in February) was especially revelatory for me, but this more modest initial dispatch from Roden's vaults is quite a treat as well. As far as I know, Oionos has not been released previously, yet it dates from a 2006 exhibition in Athens, Greece entitled The Grand Promenade. The premise of the exhibition was to create a "dialogue" between "contemporary site-specific works" and "various archaeological and historical sites in central Athens," but Roden fell in love with the Church of St. Dimitris Loumbardiardis (not among the planned sites) and managed to talk the curator into allowing an exception. Notably, the architect behind the church was the same man (Dimitris Pikionis) who designed the original promenade, so Roden's selection was a thoughtful and inspired decision, as he felt the path leading to the church provided a "stronger impression of Pikionis's vision" than the actual promenade (unlike the main promenade, the path to the church escaped being ‘restored’ in preparation for the 2004 Olympics).

Originally constructed in the ninth century using materials salvaged from surrounding ruins and described as "likely the most secluded and serene" of Athen's assortment of Byzantine-era churches, the Church of St. Dimitris Loumbardiardis is remarkably still in use. That presented something of a challenge for Roden, as his installation needed to harmonize with and enhance its peaceful environs without disrupting what made the place so alluring in the first place. He eventually decided to hang his sound installation from a large tree and opted for characteristically Roden-esque lowercase sounds that "could blend with all of the insect noises and the overall quiet of the area.” For his sound sources, Roden chose “field recordings and small ‘poor’ objects such as tin whistles, toy harmonicas, and the like." Significantly, the latter were inspired by a basement display case of "non-instruments" located in Athen's museum of musical instruments, as Roden felt the modest items meshed nicely with Pikionis's interest in blending "indigenous culture" with "intellectual and modern culture." In more concrete terms, Oionos is essentially an hour of gently whirring, whining, and crackling suspended animation. There is also a wandering, disjointed melody that calls to mind either a slowed down recording of wind chimes or a malfunctioning music box that emits sparks and feedback as it strains to produce a fitful melody. I suppose that makes Oionos a very "ambient" piece, but it can also be more than that depending on how attentively I choose to listen: sometimes it feels like fragments of a wrong-speed Andrew Chalk album floating above a rich landscape of subtle, shifting textures, while other times evokes a pleasant sense of unreality, as if submerged ghost melodies struggle to surface from a quiet haze of insectoid whines, burbling water, and gently windblown leaves. It is quite a beautifully realized piece, yet I can understand why it was not released until now, as it lingers in delicate stasis rather than undergoing any kind of significant evolution (an approach far more preferable for an installation than an album intended for home listening). Then again, Steve Roden is hardly an artist known for adhering to convention, so listeners already familiar with his oeuvre will likely enjoy basking in this meditative sound world a great deal. For the merely Roden-curious, there are probably better albums to start with, but Oionos is still strong enough to effectively convey why his work remains so revered in sound art circles.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

There are a number of fascinating small labels exploring unusual niches these days, which I suppose makes the current era something of a golden age for curious outsiders with deeply arcane interests. My favorite imprint in that vein is unsurprisingly the "open-ended research project exploring the vernacular arcana of Great Britain and beyond" that is Folklore Tapes, as their major releases exist on a plane all their own, elegantly and entertainingly blurring the lines between art, history, folklore, scholarship, music, poetry, visual art and whatever other compelling threads catch their fancy. This latest opus is characteristically another glorious cultural artifact, which is hardly surprising given the fertile nature of the subject. Nevertheless, the label have still outdone themselves, as Swifter than the Moon's Sphere celebrates the hidden history of fairy folk with an eclectic array of fairy-inspired spoken word pieces and sound art, as well as a deep and endearingly witty scholarly dive into fairy class structure and how shifting views of the supernatural mirror our society. In fact, this is one of the rare albums in which the liner notes (courtesy of Jez Winship) are every bit as compelling as the actual music ("there is something oddly impotent about the fairy aristocracy"). Beyond that, Swifter than the Moon's Sphere is a welcome return to familiar territory for the label, bringing together an inspired host of known, unknown, obscure, and enigmatic artists for a freewheeling tour de force of supernaturally charged and backwards-looking folk horror and rural psychedelia.

There are a number of fascinating small labels exploring unusual niches these days, which I suppose makes the current era something of a golden age for curious outsiders with deeply arcane interests. My favorite imprint in that vein is unsurprisingly the "open-ended research project exploring the vernacular arcana of Great Britain and beyond" that is Folklore Tapes, as their major releases exist on a plane all their own, elegantly and entertainingly blurring the lines between art, history, folklore, scholarship, music, poetry, visual art and whatever other compelling threads catch their fancy. This latest opus is characteristically another glorious cultural artifact, which is hardly surprising given the fertile nature of the subject. Nevertheless, the label have still outdone themselves, as Swifter than the Moon's Sphere celebrates the hidden history of fairy folk with an eclectic array of fairy-inspired spoken word pieces and sound art, as well as a deep and endearingly witty scholarly dive into fairy class structure and how shifting views of the supernatural mirror our society. In fact, this is one of the rare albums in which the liner notes (courtesy of Jez Winship) are every bit as compelling as the actual music ("there is something oddly impotent about the fairy aristocracy"). Beyond that, Swifter than the Moon's Sphere is a welcome return to familiar territory for the label, bringing together an inspired host of known, unknown, obscure, and enigmatic artists for a freewheeling tour de force of supernaturally charged and backwards-looking folk horror and rural psychedelia.

Like most (or all) great Folklore Tapes compilations, Swifter than the Moon's Sphere features an inspired cast of unique collaborations, house bands, unfamiliar names, and familiar names in unfamiliar roles. In the "familiar" category, we have the usual Hood Faire contingent, as well as artists like Ian Humberstone and Bridget Hayden. All are characteristically strange and wonderful, but Humberstone's "Swinging Lamps in Starlit Globes" stands as a particular highlight, resembling an eerily sliding and smeared underwater vibraphone performance accompanied by a chorus of psychedelic frogs. One of the main pleasures of a great Folklore Tapes compilation is being surprised and delighted from more unexpected corners, however, and this one is particularly rich in that regard. In fact, the opening "Genuine Leaf Fairy Sighted in English Woodland" (credited enigmatically to "DBH") is the first of many such pleasures, as harmonic sparks spray from shivering, tense strings that fitfully resolve into snatches of gorgeous melody. Brian Campbell, Peter Smyth and Carl Turney's "Requiem for the Lost" is another favorite, resembling a warm and wistful strain of post-rock backing a spacy, swooning, and dreamlike swirl of layered psychedelia.

Elsewhere, historian Jennifer Reid sings a haunting folk ballad (“Boghart Hall Clough”) about a farmer who fails to outwit a household boggart, while Emily Oldfield brings a lovely musicality to her poetry reading and Sarah Lundy goes post-everything with a spoken word piece that feels like she is casting a terrible hex on me from inside an echo chamber. Obviously, some ideas work better than others, but the artists are invariably hampered more by the constraining brevity of these pieces than by lack of inspiration (most pieces are only around two minutes long). That hurdle admittedly posed a challenge for individual artists more accustomed to working in more expansive circumstances, but the album as a whole benefits nicely from that approach, as it is a playfully shapeshifting and immersive experience that seldom wanders off course. Moreover, I will probably be quoting the liner notes for the rest of my life ("an emphasis on the grotesque and the foppishly foolish" and "this persistence of hope in the face of experience is oddly admirable" are current favorites). In fact, I was especially struck by the line "the magic power of invisibility results in fairies being more often heard or felt…than seen," as everyone involved seemed admirably devoted to getting the elusive haunted "feel" of a good fairy legend just right (no matter how much academic rigor they brought to the table). I am tempted to say that Folklore Tapes consistently offers one master class after another on how to make a meaningful, memorable, and compelling compilation, but releases like Swifter than the Moon's Sphere actually shoot past that mark to feel more like I just stumbled upon a dust-covered grimoire in a mysterious bookstore that I had never noticed before. This is an instant classic.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

Basque composer Elena Setién’s second album for Thrill Jockey is quite an unexpected leap forward from the more pop-minded Another Kind Of Revolution. While Setién's love of strong melodies and big hooks still remains mostly intact, Unfamilar Minds beautifully balances them with a host of more adventurous and psych-inspired touches, resulting in at least a half of a strikingly brilliant and unique album. The other half admittedly does not suffer from a lack of likable melodies or tight songcraft, yet Setién's work definitely needs a splash of darker, stranger sounds to curdle the wholesomeness of her more straightforward "pop" tendencies. It is an improbable and unusual mingling of stylistic threads evoking a revolving cast of seductive female vocalists getting remixed by a gnarled heavy psych project, yet Setién somehow makes it feel totally organic, natural, and all her own. Also, her throaty purr makes that unholy collision feel way more sensual and soulful than I would have expected. While it would admittedly be nice if I enjoyed the album's second half as much as the more warped and hallucinatory first half, that first half nevertheless feels enough like a revelation to make Unfamiliar Minds feel like some kind of minor masterpiece.

Basque composer Elena Setién’s second album for Thrill Jockey is quite an unexpected leap forward from the more pop-minded Another Kind Of Revolution. While Setién's love of strong melodies and big hooks still remains mostly intact, Unfamilar Minds beautifully balances them with a host of more adventurous and psych-inspired touches, resulting in at least a half of a strikingly brilliant and unique album. The other half admittedly does not suffer from a lack of likable melodies or tight songcraft, yet Setién's work definitely needs a splash of darker, stranger sounds to curdle the wholesomeness of her more straightforward "pop" tendencies. It is an improbable and unusual mingling of stylistic threads evoking a revolving cast of seductive female vocalists getting remixed by a gnarled heavy psych project, yet Setién somehow makes it feel totally organic, natural, and all her own. Also, her throaty purr makes that unholy collision feel way more sensual and soulful than I would have expected. While it would admittedly be nice if I enjoyed the album's second half as much as the more warped and hallucinatory first half, that first half nevertheless feels enough like a revelation to make Unfamiliar Minds feel like some kind of minor masterpiece.

The songs that Setién wrote for Unfamilar Minds actually date from before the pandemic, but when she revisited them after a collaborative detour with Xabier Erkizia, she felt "disconnected from the incomplete pieces made in a different reality." Consequently, she set about radically transforming her earlier ideas to reflect her "reconfigured sense of mood and perspective" and drew significant inspiration from both Emily Dickenson and conversations with Terry and Gyan Riley. That Dickenson influence manifests itself both directly and indirectly throughout the album. For example, album highlight "I Dwell in Possibility" borrows its lyrics from the poet, though it is what Setién does with them that makes the piece such a stunner. The most striking bit is the creepily autotuned vocal hook, which makes me feel uneasily like I am being serenaded by a malfunctioning android wrestling with stormy new emotions. In most other ways, however, "I Dwell in Possibility" is a representative example of the themes present in all of the album’s strongest songs: killer pop hooks blossoming out of starkly minimal chord progressions and gorgeous smears of phantasmagoric color. And, of course, it does not hurt that Setién has an absolutely wonderful voice and knows exactly how to use it.

Amusingly, Dickenson may have actually inspired the album's more psychedelic aspects as well as its lyrical themes, as Setién felt a heightened fascination with small details ("the beauty of birds, the smells from the kitchen") from our current lonely time. The swirl of delirious and hallucinatory sounds in the periphery of pieces like the warmly elegiac "2020" channel those fondly half-remembered details beautifully, transforming an already lovely song into something that evokes a flickering flock of ghostly birds.  Elsewhere, "Situation" weaves pure magic from little more than a gorgeous hook and two simple piano chords before blossoming into half-swooning/half-proggy crescendo that I did not see coming at all. My other favorite pieces are even stranger still. For example, in "Such a Drag," a seductively melancholy mantra ("it’s such a drag to be alone") languorously winds through a blackened and shuddering landscape of heavy drones to unexpectedly transcendent effect. The smoldering "This Too Will Pass," on the other hand, abandons language altogether, as Setién conjures an utterly sublime gem from warm organ drones, a frayed and wobbly melody, and swooning vocal layering. The remaining songs are a bit of a mixed bag for varying reasons, but the main theme is that the balance of poppiness and prettiness with gnarled mindfuckery was not to my liking. Perhaps those pieces will someday grow on me, but it does not matter if they do, as Unfamiliar Minds' weaker bits are easily eclipsed by its five absolutely perfect would-be singles.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

Meitei’s plunderphonic exploration of “lost Japanese moods” has been an intriguing and unusual project right from the start, but it started to blossom into something truly great with 2019's Komachi and only got better with the beat-driven breakthrough of 2020's Kofū. As it turns out, that creative leap forward was also quite an intensely prolific period and a lot of tough cuts needed to made to distill the resultant mountain of songs into a single album. As I loved Kofū, I have no qualms at all with Meitei's ruthless culling choices for that album, but it did leave a lot of finished and semi-finished pieces on the cutting room floor (somewhere around 50, in fact) and many definitely deserved a far better fate. Meitei's original plan was to just keep moving forward with new material in the wake of Kofū's success, yet "when it came time to begin his next album, he found that it had been sitting in front of him all along" and "realized his work wasn’t over yet." In that regard, Meitei's judgment proves to be unerring once again, as this selection of Songs That Did Not Make The Original Cut is every bit as poignant, wonderful, and deliriously fun as its predecessor.

Meitei’s plunderphonic exploration of “lost Japanese moods” has been an intriguing and unusual project right from the start, but it started to blossom into something truly great with 2019's Komachi and only got better with the beat-driven breakthrough of 2020's Kofū. As it turns out, that creative leap forward was also quite an intensely prolific period and a lot of tough cuts needed to made to distill the resultant mountain of songs into a single album. As I loved Kofū, I have no qualms at all with Meitei's ruthless culling choices for that album, but it did leave a lot of finished and semi-finished pieces on the cutting room floor (somewhere around 50, in fact) and many definitely deserved a far better fate. Meitei's original plan was to just keep moving forward with new material in the wake of Kofū's success, yet "when it came time to begin his next album, he found that it had been sitting in front of him all along" and "realized his work wasn’t over yet." In that regard, Meitei's judgment proves to be unerring once again, as this selection of Songs That Did Not Make The Original Cut is every bit as poignant, wonderful, and deliriously fun as its predecessor.

The more I learn about Meitei, the more I am convinced that I am only able to appreciate a mere fraction of his fascinating vision, as the layers and layers of social commentary and satire lurking in his work are hopelessly lost on me as a non-Japanese person. Consequently, I can only appreciate an album like this one on an almost purely stylistic level. Fortunately, the wistful longings and other bittersweet emotional shadings are not lost on me, yet it is a unique experience to appreciate Meitei's inventively repurposed vocal hooks, twinkling piano runs, soaring flutes, and propulsive grooves while knowing that I am probably missing many interesting allusions and celebrations of the marginalized. Then again, maybe I actually DO get everything that truly matters, as Meitei strongly believes in Hayao Miyazaki's adage "Beyond logic speaks of human nature" (I sincerely hope my subconscious is tenaciously filling in some blanks).

Meitei apparently also has a "Mizoguchi-like approach" to mingling "unimaginable pain with tenderness," which I can definitely see, as the best pieces from the two Kofū albums can feel downright ecstatic or at least beautifully cathartic: it is easy to imagine someone dancing to the crescendo of "Happyaku-yachō" or "Shinobi" with complete abandon and tear-streaked cheeks. The album's other highlights take a number of divergent directions, however, as the main stylistic thread that holds everything together is merely a passion for chopped, stammering, and warbling samples of crackling and hissing traditional music records and that seems to be very fertile creative territory indeed. "Tōkaidō," however, is yet another gem in the vein of the aforementioned two pieces, though it initially feels very "traditional" due to its central plucked string motif before the shuffling groove and ascending flute melodies kick in. The absolutely gorgeous "Kaworu," on the other hand, is quite a departure from the album's other fare, as Meitei intimately distills his vision to just a tender harp-like melody and quiet washes of tape hiss. It might actually be the single most beautiful piece on the album, but there is some additional fierce competition from the broken piano melodies and frayed ascending flutes of "Shurayuki hime" and the part in "Arinsu" where backwards melodies and an obsessively looping vocal snippet gloriously converge. Sadly, "Arinsu" is only about a minute long, which leads me to the most savage critique of Kofū II that I can muster: it may be packed floor-to-ceiling with imaginative ideas and killer unconventional hooks, but a couple of these twelve songs are admittedly shorter than the others. Hopefully that is not a deal-breaker for anyone, as this project is singular, brilliant, and seems to only get better and better with each new release.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

Hany Mehanna is a key figure in the development of keyboards in Asian music. As a young man he played accordion, organ, and synth in the orchestra of legendary singer Umm Kulthum and—along with Ammar Al-Sheriyi—learned to create quarter tones by using oscillators. In a later prolific period composing music for 93 films and 38 television series, Mehanna forged his own distinctive sound: a balance of traditional Arabic melody types or maqams and hypnotic experimental electronics. Remastered from his personal reel-to-reel tapes, this album showcases that balance on 19 otherworldly tracks. I like the fact I can never predict what any piece will sound like based on how it starts, even on very short tracks. Mehanna’s only other solo album, The Miracle Of The Seven Dances, was reissued in 2018 after being rediscovered in a record shop in Casablanca.

Hany Mehanna is a key figure in the development of keyboards in Asian music. As a young man he played accordion, organ, and synth in the orchestra of legendary singer Umm Kulthum and—along with Ammar Al-Sheriyi—learned to create quarter tones by using oscillators. In a later prolific period composing music for 93 films and 38 television series, Mehanna forged his own distinctive sound: a balance of traditional Arabic melody types or maqams and hypnotic experimental electronics. Remastered from his personal reel-to-reel tapes, this album showcases that balance on 19 otherworldly tracks. I like the fact I can never predict what any piece will sound like based on how it starts, even on very short tracks. Mehanna’s only other solo album, The Miracle Of The Seven Dances, was reissued in 2018 after being rediscovered in a record shop in Casablanca.

The album kicks off with “Hanady” blipping along like a wheezing, psychedelic, video game belly dance augmented by electric violin and the guitar of Omar Khorshid. On this track, and on the entire album, nothing is allowed to limp along into over-repetiive normality or to descend into an indecipherable mess. "Haya Ha’ira” is more raw, blasting into being with a razor blade guitar-like slashes and dazzling percussion and it’s over too soon. Bizarrely, the precisely chopped rhythm of "Walad Wa Bint” is virtually a compete blueprint for the verse singing on the early Stiff Records 45 “(I Don’t Want To Go To) Chelsea.”

“Rhela” has the kind of galloping rhythm and lustrous twang often associated with doomed British producer Joe Meek, as Mehanna throws hypnotic organ phrases over a frenzied beat. His breathtaking ability to layer electronics, strings, and solo instruments is evident on the library robo-funk of "Less Al Thulata” and the spaced out "Al Qina’ Al Za’ef” with (I think) twinkling synth, a lonely horn, smooth strings, and what sound like wah wah imitation vocals. There are actual vocals on "Dal Al Omr Ya Waladi,” an impressive dusky moaning which is a good counterpoint to the intriguing reedlike instrument which shares carrying the melody. Again, the mix is fabulous and the atmosphere beautifully relaxed.

On the cover Hany Mehanna almost looks like one of the heroic resistance fighters from Gillo Pontecorvo's documentary The Battle of Algiers, except—rather than a machine gun—he’s got an accordion strapped over his shoulder and stands in front of a small Farsifa organ. It is worth remembering that Farfisa organs have been used by everyone from Reich and Glass to Suicide and Cabaret Voltaire, as well as Giorgio Moroder, Pink Floyd, Sly Stone, Miles Davis, Percy Sledge, XTC, Sam The Sham, K.Frimpong, and Stereolab. Back on this album sleeve, Mehanna looks for all the world like he is sending a message on an early 1990s fax machine. In the top right a plane heads East across a circular object which might be a representation of the sun, or a piece of exotic garb I don’t recognize. The image is reminiscent of the cover from the cassette release Relaxation Tape For Solo Space Travel by The National Pool, the concept of which purports to be an actual aid for would-be cosmonauts. Music For Airports stays within the earth’s atmosphere but it definitely travels to some subtle and glamorous places. The album fell between the cracks a little with its December 2021 release date.

I haven’t had time to research the films and TV shows for each track, but the imagination may quickly run to mustachioed detectives, flared trousers, glamorous girls fallen in with a bad crowd, cool cars, cocktails, speedboats, nightclubs, ill-gotten gains, spies, shortwave radio, fistfights, heat and dust, baba ganoush, gloriously melodramatic day time soaps, switchblades, Sid James, cigarette holders, white dinner jackets, and all that jazz. The album title makes sense in the context of the modernizing of Egyptian economy in the 1970s, with a jet-set, Operation Nimbus Moon, and President Sadat standing on a destroyer when reopening the Suez Canal. Hany Mehanna's tunes fit in with any concept of freedom, and his rhythms showed up in popular songs which soundtracked the Arab Spring of 2010-12. This collection ends on a real high with the thrilling and poignant "Damat Alam" sandwiched between the Opening and End themes to “Al Dawarma.” No need to round up the usual suspects such as Basil Kirchin or eden ahbez. I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

With two different releases in 2021, Jim Campbell (as Rrill Bell) follows up 2020's Ballad of the External Life going in two very different thematic directions. A cassette, False Flag Rapture, is a personal, intimate work based around a recording of his grandmother, while the digital (available with printed material as well) Blade’s Return is a narrative tale about a saw (I am not sure if it is truly meant to be anthropomorphic or not). Both feel rather different from each other, but both also feature the heavy tape manipulations of Campbell, reducing instrument recordings to raw material that he shapes into entirely different and unique forms.

With two different releases in 2021, Jim Campbell (as Rrill Bell) follows up 2020's Ballad of the External Life going in two very different thematic directions. A cassette, False Flag Rapture, is a personal, intimate work based around a recording of his grandmother, while the digital (available with printed material as well) Blade’s Return is a narrative tale about a saw (I am not sure if it is truly meant to be anthropomorphic or not). Both feel rather different from each other, but both also feature the heavy tape manipulations of Campbell, reducing instrument recordings to raw material that he shapes into entirely different and unique forms.

Part one of False Flag Rapture opens with backward, swirling music with an overall gentle sensibility, even with the complex layering and textural clicking.As the sound continues to churn and sputter, Campbell balances the chaos and calm, even as a hint of menace begins to seep in.He brings in almost animalistic, growling noises, inhuman and somewhat terrifying, and everything has this odd combination of feeling familiar and natural, and yet completely alien.

On the other side of the tape, he leads off with delicate, chiming sounds before introducing a tape of his grandmother singing a Slovak hymn, which was the thematic impetus for this work.Besides this, and fragments of conversation from the same recording, he keeps things lighter with sustained, muffled tones and lots of chimes and bells, suiting the hymnal nature of the thematic core of the piece.

Samples can be found here.

Compared to False Flag Rapture, the conceptual framework of Blade’s Return is far less subtle.Deemed "an audio fable" by Bell, it tells the story of a handsaw that regrets its days used to cut down trees and thus tries to atone for its sins within the forest.The use of a musical (singing) saw is the most obvious manifestation of this theme but with the exception of a spoken introduction to the five pieces, the story is told purely through processed recordings.

Beyond the playing of the saw, Bell works again with heavy tape manipulation, along with less manipulated environmental recordings from Switzerland.The saw often takes the lead, such as the scraping on "The Return" or as shrill, bowed tones throughout "Lament."The latter is also a standout via tape manipulation, where Campbell creates a scene of a haunted forest, complete with animals in the distance.The shorter closing pieces "Atonement" and "Release" feature largely sparse mixes, with the former casting expansive tones far in the distance, and the latter blending in sounds of water and other environmental sounds.

Campbell certainly succeeds in the lofty goals for both of these releases:Blade’s Return is a narrative driven (almost exclusively) by sound, and False Flag Rapture captures the personal and intimate, but also a healthy dose of mystery.Both releases outline the instrumentation he used for the recordings, but it is only recognizable a fraction of the time.As Campbell treats and manipulates the instrumental sounds, it becomes something entirely different, mysterious, confounding, and captivating.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

With apologies to Laurie Speigel after whose album the label takes its name (and Sylvia Tarozzi), it must be said that solo piano is at the core of Unseen Worlds. Their standards are high, as evidenced by recent releases such as James Rushford's Musicá Collada/See The Welter and "Blue" Gene Tyranny’s Detours. Human Remains is Robert Haigh’s third (and best) release for the label. His composition and playing superbly balance immediacy and detachment. This balance places a subtle disguise or mystery over these compositions. I detect a similarity with the approach of Werner Herzog in many of whose films the audience is allowed to feel and react without heavy-handed close ups.

With apologies to Laurie Speigel after whose album the label takes its name (and Sylvia Tarozzi), it must be said that solo piano is at the core of Unseen Worlds. Their standards are high, as evidenced by recent releases such as James Rushford's Musicá Collada/See The Welter and "Blue" Gene Tyranny’s Detours. Human Remains is Robert Haigh’s third (and best) release for the label. His composition and playing superbly balance immediacy and detachment. This balance places a subtle disguise or mystery over these compositions. I detect a similarity with the approach of Werner Herzog in many of whose films the audience is allowed to feel and react without heavy-handed close ups.

Robert Haigh is well known to brainwashed, of course, as a veteran of the UK underground since around 1980 via Nurse With Wound, Omni Trio, Silent Storm, Sema, and Truth Club. He is a natural fit for Unseen Worlds since, as he has said, piano is at the root of all his compositions. My view is that his solo piano works should have him up to his ears in film commissions, as they are jammed to the gills with poignant and unfussy (or anti-virtuosic pieces) and imbued with an essential immediacy and detachment. On earlier records, Haigh has borrowed titles from film, such as "Juliet of The Spirits” and “Ipcress Girl,” so I am guessing that he would take on the right project. An excellent longer piece on Human Remains titled “Signs of Life” got me thinking about Werner Herzog—since he made a film of that name. Herzog has argued, in one of his more believable utterances, that filmmaking is about creating immediate and profound connections with people. Robert Haigh certainly makes music according to that axiom and seems also to follow another choice of the master filmmaker. In the book A Guide For The Perplexed, Herzog mentions his decision to not move the camera in too closely to an actor’s face, since it will be “more fascinating to the audience if they see you as big as an ant in the landscape.” He adds “I have never wanted to see an actor weep. I want to make the audience cry instead.”

Haigh has identified his influences as including Chopin, Debussy, Satie, Budd, Feldman, Glass, Eno (both Brian and Roger), Evans, Cosma, Mompou, and Mertens, yet he usually manages to sound like himself by never overtly aping any style or approach. That said, the clarity and pace of "Contour Lines" could pass for a romantic Cosma piece from the soundtrack to the movie Diva (1981). There is no dud on Human Remains although there is a varied range. "Baroque Atom" adds rhythmic string slashes to the mix and showcases the "shifting pattern" aspect of Haigh’s composing. "Waltz on Treated Wire" may be a nod to John Cage and the concept of prepared piano (which goes back to 1938 with Cage, but also shows up even earlier with Henry Cowell* and Maurice Delange). His natural talent for organic improvisation is all over this recording, not least on the lovely final piece "Terminus Hill" the title and tone of which suggest a natural end point. Soundtrack work could be his next horizon. If I were a music supervisor for films, Robert Haigh’s name would be high on my list. God knows he would have vastly improved some of the things I’ve watched in the past few years.

*Maybe I finally got the joke about the name of the group Henry Cow.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

At this point, I consider myself quite well accustomed to Markus Popp's penchant for bold stylistic reinventions, yet this latest album managed to completely blindside me nevertheless. To be fair, however, Ovidono is not quite a pure Oval album, as Popp is joined by return collaborator Eriko Toyoda and artist/actress Vlatka Alec. The latter, in fact, is responsible for the album's concept: transforming the poetry of Ovid and Ono No Komachi into sound art that evokes "the tactile, immersive quality and intimacy of ASMR." The trio definitely succeeded in that regard, as Ovidono is probably the finest ASMR-inspired album that I have yet heard, but it is also a bit more ambitious than just a hallucinatory swirl of hushed and sibilant voices. Obviously, that would have been just fine by me too, as Popp is an absolute wizard at chopping and reassembling sounds. However, Ovidono is also quite compelling compositionally, as Alec and Toyoda's voices are backed by music that lies somewhere between noirish torch song, deconstructed piano jazz, and the uneasy dissonances of Morton Feldman.

At this point, I consider myself quite well accustomed to Markus Popp's penchant for bold stylistic reinventions, yet this latest album managed to completely blindside me nevertheless. To be fair, however, Ovidono is not quite a pure Oval album, as Popp is joined by return collaborator Eriko Toyoda and artist/actress Vlatka Alec. The latter, in fact, is responsible for the album's concept: transforming the poetry of Ovid and Ono No Komachi into sound art that evokes "the tactile, immersive quality and intimacy of ASMR." The trio definitely succeeded in that regard, as Ovidono is probably the finest ASMR-inspired album that I have yet heard, but it is also a bit more ambitious than just a hallucinatory swirl of hushed and sibilant voices. Obviously, that would have been just fine by me too, as Popp is an absolute wizard at chopping and reassembling sounds. However, Ovidono is also quite compelling compositionally, as Alec and Toyoda's voices are backed by music that lies somewhere between noirish torch song, deconstructed piano jazz, and the uneasy dissonances of Morton Feldman.

The opening "Dormant" does a fine job of setting a suitably bleary, haunted, and hallucinatory mood, as tumbling minor key piano melodies cast a spell of unease beneath a flickering swirl of ghostly whispers. The music reminds me a bit of some of the prepared piano pieces from Aphex Twin's Drukqs, but a more fluid and melodically sophisticated version. If Ovidono was simply nine subtly nightmarish piano miniatures in the same vein, it would probably be a legitimately excellent album, but "Dormant" feels like a goddamn masterpiece with the added layers of Alec and Toyoda's seductively hissing, popping, and clicking voices panning around my head. Wisely, Popp does not make any drastic changes to that winning formula for the other pieces, but he does vary the tone enough to give each piece its own distinct character. For example, the second piece ("Lost in Thought") features ghostly flutes and vocals of a more stammering and fluttering nature that seem to dissolve into a rain of clicks and pops. "As I Do" is a bit more of a departure, however, as it initially feels like I am trapped inside a haunted music box with a conspiratorial Japanese ghostess. As it progresses, however, it becomes increasingly spacy and blossoms into an immersively chiming and quivering fantasia of harp-like sweeps and Gilli Smyth-style space whispers. Yet another highlight is "Feeling," which evokes a melancholy pianist sadly twinkling his way across the keys in a nearly empty, neon-lit bar (a scene nicely enhanced by the hushed and flickering voices burrowing psychotropically into my subconscious). The closing "Over" is another personal favorite, as Popp's piano takes a brighter tone that is further warmed by shimmering and droning strings. It has a simple straightforward beauty that I do not normally associate with Popp's work, but I quite like it and the sibilant swirl of sensuous voices around it makes for good company. The remaining pieces are all similarly strong and offer their own twists, so I expect some of them will someday become favorites as well. Then again, I cannot foresee myself ever having much urge to single out an individual piece, as this entire goddamn album is brilliant.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

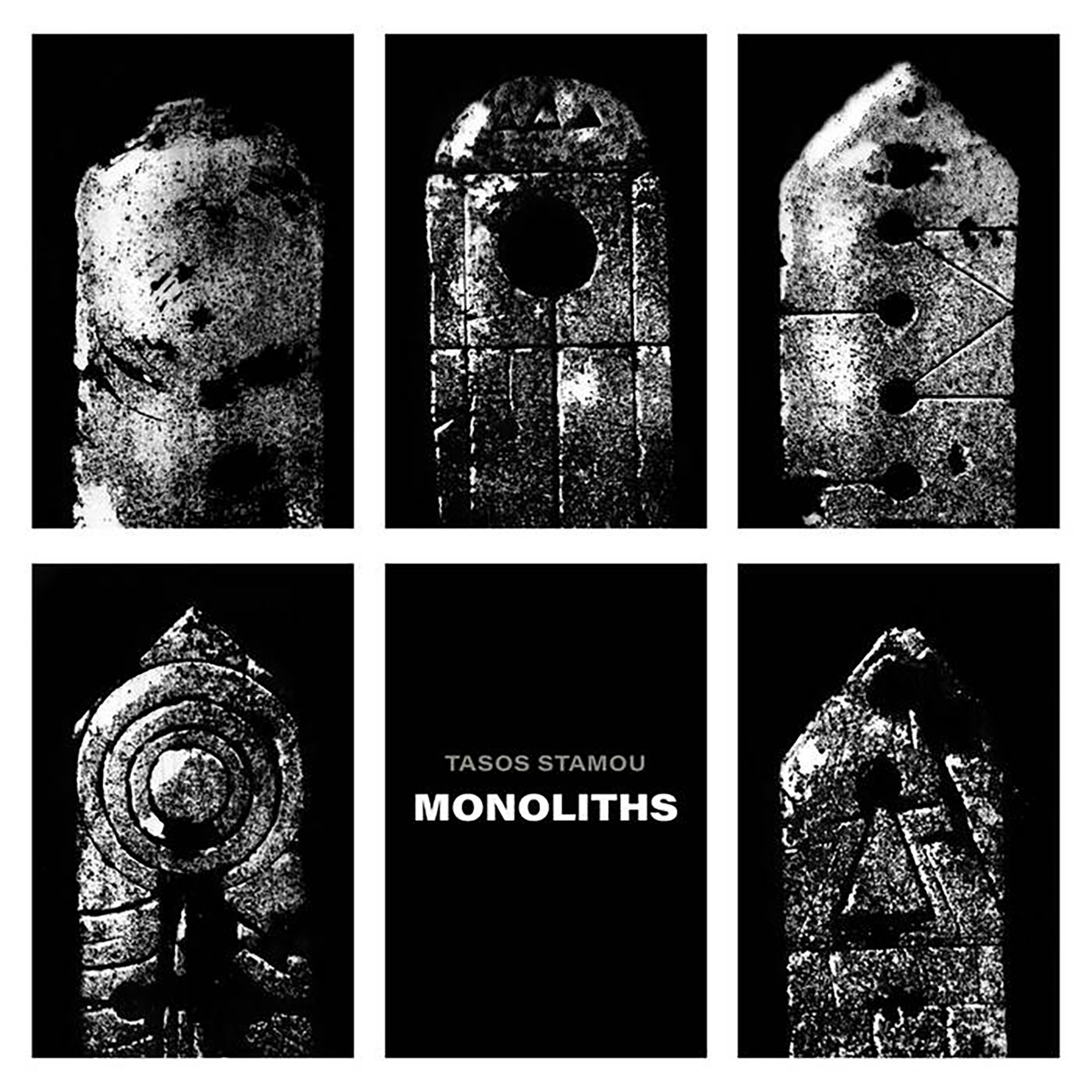

Discovering this London-based composer's adventurously psychedelic collages of traditional Greek music was one of 2021's great musical pleasures for me, so I was very eager to hear this ambitious double album follow up to Antiqua Graecia. As expected, it is a characteristically wonderful and unusual release, but it is also marks a detour away from Stamou's impressive run of Greek-themed albums. The theme of the aptly titled Monoliths is instead Stamou's attempt to "collide" the two sides of his working methods: live performances and studio work. By my estimation, it was a very successful collision, but it was mostly a behind-the-scenes one, as I would be hard pressed to determine where one approach starts and another begins. As a result, the more immediate and striking theme of the album for me as a listener is that each piece feels like an extended experiment in crafting an immersive, complexly layered sound world from just a single recognizable instrument. At least, that is how Monoliths unfolds for its first half, as the bottom drops out of the album's hallucinatory feast of bells, organs, and steel drums to reveal a considerably more processed, abstract, and psychotropic second hour of drone-damaged mindfuckery. That approach admittedly makes Monoliths a bit less accessible than some of Stamou’s more conventionally melodic work, but serious heads looking for a deep and sustained dive into otherworldly psych meditations will likely love this immersive tour de force.

Discovering this London-based composer's adventurously psychedelic collages of traditional Greek music was one of 2021's great musical pleasures for me, so I was very eager to hear this ambitious double album follow up to Antiqua Graecia. As expected, it is a characteristically wonderful and unusual release, but it is also marks a detour away from Stamou's impressive run of Greek-themed albums. The theme of the aptly titled Monoliths is instead Stamou's attempt to "collide" the two sides of his working methods: live performances and studio work. By my estimation, it was a very successful collision, but it was mostly a behind-the-scenes one, as I would be hard pressed to determine where one approach starts and another begins. As a result, the more immediate and striking theme of the album for me as a listener is that each piece feels like an extended experiment in crafting an immersive, complexly layered sound world from just a single recognizable instrument. At least, that is how Monoliths unfolds for its first half, as the bottom drops out of the album's hallucinatory feast of bells, organs, and steel drums to reveal a considerably more processed, abstract, and psychotropic second hour of drone-damaged mindfuckery. That approach admittedly makes Monoliths a bit less accessible than some of Stamou’s more conventionally melodic work, but serious heads looking for a deep and sustained dive into otherworldly psych meditations will likely love this immersive tour de force.

The opening "Bells Drone" sounds deceptively like it could be layered field recordings of wind chimes at first, as bells of different sizes amiably jangle and clang for couple minutes before any real evidence of Stamou's hand starts to emerge. Soon, however, some tones start to linger supernaturally and the mood darkens into uneasy shadows of dissonance. It is quite a wonderfully hallucinatory and entrancing piece, evoking an ancient ritual in a cavernous subterranean temple revealed behind a dissolving reality. While it is the shortest piece on the album at a mere 13 minutes, it is nevertheless a solid representation of the album’s first half: a simple and minimal theme gradually transforms into a vividly multi-dimensional dream world. On "Chord Organ #2," for example, an organ drone slowly evolves into a Catherine Christer Hennix-esque nightmare of dark harmonies before unexpectedly resolving on a note of sundappled transcendence. "Steel Drum Drone," on the other hand, steadily becomes something akin to a lovesick tropical Steve Reich. That one is another favorite, as I am quite impressed with how Tasos weaves together patterns of plinking and bleary steel drum melodies into a thing of woozy multi-layered beauty.  In fact, I love every single one of the opening three pieces, but they turn out to be a mere prelude to two pieces in which Tamou goes totally bananas. In the first, "Supernormal," Stamou mingles a chirping electronic drone with squealing and sliding strings en route to an harrowing mindfuck that calls to mind a goddamn demon summoning (the final stretch of oscillating synth thrum is especially choice). The closing "Synapse" improbably features some even more gnarly sounds, passing though such colorful stages like "menacingly gelatinous bass throb," "an undead gamelan ensemble wanders the deserted streets in search of their next victim," and "a simmering and intense prepared piano performance over quasi-industrial rhythmic loops." This is an absolute feast of an album: five great longform pieces in a row spanning nearly two hours. Most days, I admittedly prefer the more meditative/ritualistic first half to the more nightmarish second half, but Stamou was swinging for the fences with every single piece on this album and the result is a monolithically stellar release.

Samples can be found here.

Read More