- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I Shall Die Here is the fourth full-length album by The Body. Sharing their moribund vision for I Shall Die Here with Bobby Krlic (aka The Haxan Cloak), the tried and true sound of The Body is cut to pieces, mutilated by process and re-animated in a spectral state by the newly minted partnership.

The Body's brutal musical approach, engraved by drummer Lee Buford's colossal beats and Chip King's mad howl and bass-bladed guitar dirge, becomes something even more terrifying with Krlic's post-mortem ambiences serving as both baseline and outer limit. I Shall Die Here sonically serrates the remains of metal's already unidentifiable corpse and splays it amid tormented voices in shadow.

According to the band themselves, they sought to create something wholly experimental with I Shall Die Here. In the course of its creation and recreation, they have attained that rare artistic goal: an album with few precedents and a paradigm shift richly realized. Bobby Krlic's downcast electronic visions laces seamlessly into The Body's already volatile mix of fissured doom metal and fused verbal spaces. The onset of a new music emerges with I Shall Die Here, and in its shifts, shadows, and reeling voices, the darkest possible formulation of electronic music has been realized.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

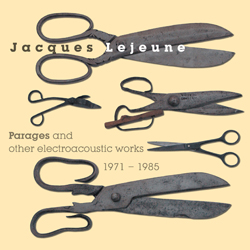

Robot Records’ three-CD retrospective of Jacques Lejeune’s music from the early 1970s and 1980s contains over three hours of heady electronic noise, surreal acoustic transformations, deconstructed field recordings, and disorienting aural splutter. It is a collection that spans 14 years and six electroacoustic compositions: one composed for ballet and inspired by Snow White, another inspired by the myth of Icarus, and others by landscapes, symphonic form, and cyclical movement, among other things. They flash with theatrical flair, jump unpredictably through minute variations, and churn chaotically, tossing fabricated scree and instrumental slag into the air. A 28 page bilingual booklet filled with photographs, drawings, and program notes accompanies the set, along with a 32 page booklet of interpretive poetry. In them, Lejeune, Alain Morin, and Yak Rivais offer up remarkably precise interpretations for each of the pieces, but the writing works much better as a rough guide to the visually evocative clamor of Lejeune’s electric transmissions.

Robot Records’ three-CD retrospective of Jacques Lejeune’s music from the early 1970s and 1980s contains over three hours of heady electronic noise, surreal acoustic transformations, deconstructed field recordings, and disorienting aural splutter. It is a collection that spans 14 years and six electroacoustic compositions: one composed for ballet and inspired by Snow White, another inspired by the myth of Icarus, and others by landscapes, symphonic form, and cyclical movement, among other things. They flash with theatrical flair, jump unpredictably through minute variations, and churn chaotically, tossing fabricated scree and instrumental slag into the air. A 28 page bilingual booklet filled with photographs, drawings, and program notes accompanies the set, along with a 32 page booklet of interpretive poetry. In them, Lejeune, Alain Morin, and Yak Rivais offer up remarkably precise interpretations for each of the pieces, but the writing works much better as a rough guide to the visually evocative clamor of Lejeune’s electric transmissions.

Jacques Lejeune’s musical career began auspiciously, at the famous Schola Cantorum de Paris, a private music school in the city’s Latin Quarter whose alumni include Edgard Varèse and Erik Satie. From there, he moved to the Conservatoire National Supérieur, where Adolphe Sax had once taught and where Igor Wakhévitch would eventually study, and labored under the tutelage of Pierre Schaeffer. He finished his education with François Bayle at the Groupe de Recherches Musicales, then joined the GRM in 1968 and became director of the Cellue de la Musique pour L’Image, or The Department of Music for Images, responsible for the production of sound and music for both theater and television.

By 1971 he had finished his first major composition, Cri, which premiered at the Royan Festival in 1972. It was Lejuene’s introduction to France and the first indication that his stint in the Images Department at the GRM had been as formative as the rest of his education.

Early on, Cri delivers brief, sometimes confounding glimpses of particular places and circumstances. Those images are held in focus just long enough to be recognized and then swept away: a marching band stomps through a busy street in the first movement, then disappears into the sound of French horns warming up before a performance; frogs croak in concert with crickets as sheets of tape noise flutter by imitating the sound of water; people laugh and conversations crash against bursting radio signals and gusts of analog distortion. In the second movement entire sentences survive, accompanied by reverse audio and a small gaggle of test tones. Exclamations leap out of the commotion and a radio transmission about Pakistan and the United States floats smoothly by, like a small town seen from the window of a passing train.

Lejeune introduces the skull-pounding sounds of a construction site later in the piece, but not before dampening the mood with desperate cries, rushing sirens, and the sinister crack of jackboots on concrete. The final movement is similarly ominous, though not as visually striking. Synthetic tones and surface noises replace the recognizable audio of the previous movements, and these become louder and gain more and more momentum until, near the finale, they crescendo in one long animal-like groan. The final minutes are calmer and more reflective, like a single wide-angle shot of the entire composition. The camera holds its gaze as people walk obliviously through the frame, and then the shot fades to a quiet, contemplative black.

Pieces like Parages, finished two years later, and Symphonie au bord d’un paysage, completed in 1981, also contain familiar worldly fragments, but in both works Lejeune so thoroughly transfigures his sounds that the familiar in them disappears. The focus shifts from the presentation of images to their transformation. Seagulls mix with squawking machines and squeaky hinges during one small section of Parages, calling our attention to the quiet pleasure of household noises. Moments later a series of sine waves and a brief flute passage swallow an entire church organ whole. Symphonie moves through several such transformations too: turntables start and stop, loose floorboards bend and creak under the weight of someone’s shoes, and numerous electronic reverberations zip like lightning through the mix. A few such reverberations repeat themselves, but most erupt in seemingly improvised and unrepeatable fits. Parages is particularly varied, moving at such a pace and with such variation that getting lost among its many mutations is inevitable.

It is an impressive and dynamic piece, but Robot could have easily named the collection after 1975’s Blanche-Neige, Lejeune’s incredible production for Fantasmes, ou l’histoire de Blanche-Neige, a ballet adapted from the Grimm Brothers’ version of Snow White by Yves Boudier and Catherine Escarret. Instead of simply composing music for the ballet, Lejeune creates an entirely self-sufficient audio version of the fairytale, using vocal snippets, sounds effects, and collaged motifs to represent the characters, places, and actions in the story. We can hear birds crying in the forest and monsters walking secretly in the dark during "Solitude of Snow White in the Nocturnal Forest," and Snow White, made wholly present by the inclusion of just a few fragmented sounds, gasps through every four tense minutes of it, panicking in response to the insects and night creatures that crawl by. Lejeune plunges into Snow White’s head and makes the tightness in her chest palpable one small detail at a time.

"The Hunter’s Race Dragging Snow White," on the other hand, gallops along quickly, pitched forward by vocal samples clipped so short they read as street percussion. Pots and pans and buckets belch muted vowels and abbreviated exclamations to the tune of sine waves and low, agitated drones. It is a frightening sequence, effective because all of its elements—the horse, the hunter, the sudden movements, Snow White’s confusion, and the gnarled forest path—are all depicted with perfect clarity.

Lejeune’s touch is delicate enough to handle light, color, and humor too. He takes pianos, harps, random stringed instruments, and bells to the chopping block, and then turns them into wavy, dream-like apparitions. During Snow White’s funeral, he uses awkward, honking voices to represent the dwarfs’ lamentations, rather than the usual melancholic singing. In place of the expected solemn dirge we get a line of mechanical toys bleating a lost and tuneless song. It’s a small bit of comedic relief, but a welcome one. Later, as the evil queen approaches her death, Lejeune cuts triumphant drums against operatic vocals modified to portray screams. It’s the sound of the queen protesting on the way to her execution, histrionic and larger than life. That spectacle carries through to the conclusion, where echoes of the prince’s earlier scenes are married to sounds used during Snow White’s solo appearances. The ballet ends happily, with birds singing and the happy couple riding off into a wobbly, harp-filled sunset—it’s a perfect storybook ending to a piece of music that, more than anything else, behaves like a story.

For that reason, nothing else in the set sounds quite like Blanche-Neige. As with Parages and Symphonie, Les palpitations de la forêt, from 1985, includes several recognizable snippets among its battery of vibrations, but all the drama consists in the way those snippets are transformed, not in what they represent. The same can be said of 1979’s Entre terre et ciel. In these shorter pieces (still almost half an hour long) Lejeune steps out of the role of director and into the role of scientist. He places his material under a microscope, analyses the forces at play, then smashes everything to atoms, stretching some sounds to oblivion and restoring others to a semi-familiar state. The crux of the music consists in the elemental features revealed by this process: space, time, density, frequency, repetition, variation, volume, and memory all come to the fore; representation, melody, and narrative recede into the background. The landscapes and human references are still present—small streams, duck calls, muted fireworks, and so on—but they’re at the service of these building blocks.

Other composers from the GRM have used similar techniques in their work, as the recent glut of GRM reissues can attest. Bernard Parmegiani, Luc Ferrari, Jean-Claude Risset, and many others experimented with pre-recorded and acousmatic sounds, using them to play with form and to extend their musical vocabulary to regions far beyond the reach of acoustic instruments and traditional notation. In that sense, Jacques Lejeune’s music is part of an experimental tradition that took root in France during the 1940s. He learned his craft from the musicians and inventors responsible for its development and, to some degree, carried their interests and concerns into his own work. But his treatment of images and his focus on the theatrical and dramatic potential of musique concrète make him unique.

By gathering of all these pieces into one place, Robot has emphasized that uniqueness in a way that a single LP release, or even a triple gatefold deluxe LP release, couldn’t. The chronological presentation of Lejeune’s work, in combination with the remastered audio and uninterrupted playback, makes approaching and appreciating the music easier. The book of poetry and the program notes, despite their sometimes labyrinthine and overwrought language, do the same. The result is a smartly presented, perfectly focused snapshot of one of the GRM’s lesser known members, one that has long deserved such a considerate, thorough, and excellent retrospective.

samples:

- "The Icarus Cycle," from Parages

- "The Hunter's Race Dragging Snow White," from Blanche-Neige

- "Animated," from Symphonie au bord d'un paysage

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Christopher King, the artist behind Symbol, has been prolific for a number of years, as the founding member and guitarist for This Will Destroy You, creating film scores, and spending time in other local Austin bands. Online Architecture, however, is his first truly solo release. Across six compositions juxtaposing lush electronics with decaying analog media, the album has a familiar warmth while never shaking the feeling of something sinister just beneath the surface.

King intentionally dubbed his recordings from modular synthesizers and effects onto decaying 1/4" and 1/2" inch magnetic tape, utilizing the fragmenting sound as an instrument unto itself, a natural form of post-production that no software plug-in could fully approximate.Inevitably there are some parallels to be drawn to William Basinski's Disintegration Loops, but the two are completely distinct and separate entities that happen to use a similar technique.

The opening piece, "Tracer," is probably the lightest one.What sounds like it could almost be guitar is mixed with keyboards and covered in a sun-baked, crumbling layer of reverb.Both due to its instrumentation and its decrepit source material, it feels like revisiting a collection faded memories from the late 1970s.Beyond that things start to get a bit more unsettling.

"Shadow Harvesting" sits amid a lo-fi ambience, crackling tape and mechanical sounds covering an organ-like repeating synth pattern.Compared to "Tracer," it is a bit more skeletal, and because of this it brings a sort of insinuated creepiness that reappears throughout the album."New China" comes together similarly, with sad synth tones forming the foundation with almost rhythmic loops defining the rest of the piece.

Things do slip more into dissonance once "Syn Cron" hits its stride: a noisy, almost guitar like sound leads the way, with other, more gentle layers lightly drifting from channel to channel.The more ragged sounds hide low in the mix on "Clear Passage," beneath shimmering, string-like tones and soft electronic passages.The long closing piece, "Lineage," initially has a more malignant feel through some sinister synth pulses at its introduction, but later drifts into a sad, yet hazy and hallucinogenic outro.

King’s first release as Symbol is hard to consider a debut given his involvement in many other bands and projects, and the influence of those projects resonate in Online Architecture.Complex, moody, and fascinating, it is the use of analog decay and damage that give this album its distinct identity, and help it to stand out brilliantly amongst so many other synth heavy records.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Andrew Lagowski's S.E.T.I. project has been constructing dark ambient dramas with an extra-terrestrial sensibility for over 20 years, blending unidentifiable electronic passages with moments of identifiable synthesizers or samples, and Final Trajectory is the culmination of that. Culled from 30 years of recordings, this album drifts from fascinating to terrifying, much like massive expanse of the universe that influenced it.

Andrew Lagowski's S.E.T.I. project has been constructing dark ambient dramas with an extra-terrestrial sensibility for over 20 years, blending unidentifiable electronic passages with moments of identifiable synthesizers or samples, and Final Trajectory is the culmination of that. Culled from 30 years of recordings, this album drifts from fascinating to terrifying, much like massive expanse of the universe that influenced it.

Consisting of a single, nearly hour long piece, the album first begins with dramatic sweeps of electronics; lush synthesizer pads clashing with chirpy, modular electronic noises that prevent the music from ever becoming too calm.Just as the backing layers begin to drift off into a soft, pensive bit of spaciousness, the erratic outbursts cut through like static on a distant radio transmission.

Between these dissonant moments, the remainder builds to a cold ambience that vacillates between peaceful and bleak, blending the quiet keyboards with fuzzy waves of electronics.As the piece goes on, the calmer moments are broken up not by abrupt electronics but by heavily processed voice samples that sound simultaneously human and alien, either heavily effected by interference or the sound of another organism entirely.

This cycle of dramatic, yet sparse electronics with sharp, dissonant outbursts is the recurring motif of Final Trajectory.Synth strings build to a quiet, yet tense level to be interrupted by heavily processed samples, electronic blips, or stuttering, digital glitches.At times, even without the interruptions, the more traditional keyboard passages take on a darker, more aggressive direction.

While it might have a clearly cyclic structure to it, there is an overarching progression to the piece that slowly builds its way into a noisier, crackling near apocalypse of sound to then lightly drift away peacefully in the darkness.The metaphor of space travel and the unknown is a recurring theme amongst many electronic artists, but only a handful manages to do it as well as Lagowski.The symbolism is overt, and at times the approach may lean into science fiction more than theoretical astrophysics, but those are the moments that keep Final Trajectory unique and compelling.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I have noted in the past that few artists are quite as chameleonic as Barn Owl, an observation that Jon Porras seems to have taken as a challenge, as he has now gone and made a dub techno album.  While I do not think that he should necessarily quit his day job, the better moments of Light Divide make it seem like Porras has been doing this forever.  In particular, the opening, "Apeiron," is 7-minutes of warmly hissing greatness.  The rest of the album is not quite on the same level, but it is certainly a pleasant and well-executed stylistic departure nonetheless.

I have noted in the past that few artists are quite as chameleonic as Barn Owl, an observation that Jon Porras seems to have taken as a challenge, as he has now gone and made a dub techno album.  While I do not think that he should necessarily quit his day job, the better moments of Light Divide make it seem like Porras has been doing this forever.  In particular, the opening, "Apeiron," is 7-minutes of warmly hissing greatness.  The rest of the album is not quite on the same level, but it is certainly a pleasant and well-executed stylistic departure nonetheless.

As divergent as dub techno initially seems from Porras' drone-heavy past, the connecting threads are evident right from the very beginning of "Apeiron," as it is built primarily upon a single sustained synth chord.  The key difference is that Jon now leaves that backbone alone to quaver gently over a deep bass thump and echoing, processed percussion rather than using it as a foundation for more layers of guitars and synthesizers.  Porras' old melodic/harmonic sensibilities still remain as well: they are just a bit buried this time around–pleasantly so, actually.  By the time "Apeiron" finally ends, there is enough subtle darkness and complexity swirling in the warm and eerie haze that it ultimately sounds a lot more like Angelo Badalamenti than, say, Pole.

Jon does not quite keep that remarkable feat going for the remaining four songs, but he is not short of good ideas nor is he a slouch at executing them.  In fact, the sole flaw with Light Divide lies mostly with Porras' odd compositional choices, as every other piece takes some kind of momentum-sapping detour around its midpoint.  "Recollection," for example, is a bit more active melodically than its predecessor, weaving together a ghostly nimbus of drifting and shimmering synths.  Unexpectedly, however, Porras undercuts that with a cavernous thump and rumble that almost veers into singularly dancefloor-unfriendly Lustmord territory before the piece ultimately dissipates into a beat-less coda of woozily rippling synths, hissing swells, and reverberating chords.

The following "Divide" initially ditches the dark ambient tendencies to take another crack at the successful formula of "Apreiron," but abruptly dissolves into gloomy rumbling and clattering after about two minutes as well.  That disappointed me, though the piece is redeemed a bit by the gradual fade-in of some gently flanging and hallucinatory synth chords.  "New Monument," on the other hand, is a warmly drifting drone piece augmented by plenty of echoes, hisses, and buried shudders.  Unfortunately, Porras again decides to completely stop the song and changes motifs halfway through.  The problem is not that the new motif is particularly weak–it is just that it feels sudden and puzzling.  A five-minute song is probably too short for multiple movements unless an artist is a master at seamless, organic-feeling transitions, which is one skill that Jon cannot currently boast.

Light Divide concludes with the strong "Pleiades," which reprises the album's themes of echoing clatters, buried throbs, and quavering synths, but does it a bit better than some of the previous pieces.  I especially enjoy how overloaded the sub bass sounds.  Naturally, that theme does not last, but the pulsing drone that replaces it is perhaps even better.  Ultimately, that all adds up to a characteristically likable, but somewhat minor and exasperating effort from Porras.  I definitely wish the rest of Light Divide had lived up to the great promise of "Apeiron" or at least given its various grooves and themes more time to properly unfold, yet I suspect the drone-damaged, "fits-and-starts" nature of these pieces was an intentional move in order to do something distinctive rather than lapsing into mere dub techno pastiche.  I bet Light Divide could have been quite a great pastiche though.

Samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Based in Montreal, Kyle Bobby Dunn has been producing elegant and refined works of ambient minimalism for the better part of a decade. His two lengthy and critically lauded collections for the Low Point label, A Young Person’s Guide… and Bring Me the Head of…, established him as a force to be reckoned with in the current epoch of drone/ambient music. Indeed, he is a rare artist whose compositions offer listeners wonder, sadness and pathos in equal measure, and are executed with a precision and effortlessness that eludes most musicians working in the genre.

With Kyle Bobby Dunn and the Infinite Sadness, he has produced what is undoubtedly his most focused and emotionally charged work thus far, a rich, expansive collection of slowly unfurling beauty that stretches out over the course of more than two hours. Dunn's trademark guitar swells and slow-moving loops are present here, but feel clearer and with a renewed sense of purpose and poise. He recorded source material for the album in various Canadian towns, including Belleville and Dorset, and processed and arranged the recordings at L'auberge de Dunn Studios in Montreal while, in his own words, "reflecting heavily on the gorgeous feet of a certain French woman and binging on strong beers and cheese."

From the opening salvo, "Ouverture de Peter Hodge Transport," Dunn establishes a haunting, lovelorn trajectory that is developed through pieces such as the strikingly beautiful "Boring Foothills of Foot Fetishville" and the poignant closer "And the Day is Dunn and I Can Only Think of You," titles which exhibit well his trademark sense of (black) humor. A powerful statement and what is at once the artist's most complex, complete and accessible album to date, we’re pleased and honored to present "Kyle Bobby Dunn and the Infinite Sadness."

More informational is available here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Young God Records is delighted to announce the release of a new album, To Be Kind, out on May 13, 2014. The album will be released on Young God Records (North America) and Mute in the rest of the world.

A NOTE FROM MICHAEL GIRA:

Hello There,

We (Swans) have recently completed our new album. It is called To Be Kind. The release date is set for May 13, 2014. It will be available as a triple vinyl album, a double CD, and a 2XCD Deluxe Edition that will include a live DVD. It will also be available digitally.

The album was produced by me, and it was recorded by the venerable John Congleton at Sonic Ranch, outside El Paso Texas, and further recordings and mixing were accomplished at John's studio in Dallas, Texas. We commenced rehearsals as Sonic Ranch in early October 2013, began recording soon thereafter, then completed the process of mixing with John in Dallas by mid December 2013.

A good portion of the material for this album was developed live during the Swans tours of 2012/13. Much of the music was otherwise conjured in the studio environment.

The recordings and entire process of this album were generously and perhaps vaingloriously funded by Swans supporters through our auspices at younggodrecords.com via the release of a special, handmade 2xCD live album entitled Not Here / Not Now.

The Swans are: Michael Gira, Norman Westberg, Christoph Hahn, Phil Puleo, Thor Harris, Christopher Pravdica.

Special Guests for this record include: Little Annie (Annie sang a duet with me on the song "Some Things We Do," the strings for which were ecstatically arranged and played by Julia Kent); St. Vincent (Annie Clark sang numerous, multi-tracked vocals throughout the record); Cold Specks (Al contributed numerous multi-tracked vocals to the song "Bring the Sun"); Bill Rieflin (honorary Swan Bill played instruments ranging from additional drums, to synthesizers, to piano, to electric guitar and so on. He has been a frequent contributor to Swans and Angels of Light and is currently playing with King Crimson).

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Mute is delighted to announce the release of Ben Frost’s next record A U R O R A, out on May 26, 2014. This is Frost's highly anticipated fifth solo release, his first since the widely acclaimed BY THE THROAT from 2009.

These lean, athletic visions seem to stand testament to a kind of survival – a proof of life. Muscular shapes maintained only to a level of functioning physical survival, of necessity, and no further; filthy, uncivilized, caked in sweat, and battery acid.

Starved of all the adornments of its predecessor; wholly absent of guitar, of piano, of string instruments and natural wooden intimacy, A U R O R A offers a defiant new world of fiercely synthetic shapes and galactic interference, pummeling skins and pure metals.

Performed by Ben Frost with Greg Fox (ex-Liturgy), Shahzad Ismaily and Thor Harris (SWANS) and largely written in Eastern DR Congo, A U R O R A aims directly, through its monolithic construction, at blinding luminescent alchemy; not with benign heavenly beauty but through decimating magnetic force.

This is no pristine vision of digital music; but an offering of interrupted future time, where emergency flares illuminate ruined nightclubs and the faith of the dancefloor rests in a diesel-powered generator spewing forth its own extinction, eating rancid fuel so loudly it threatens to overrun the very music it is powering.

And so, is the ongoing evolution of Frost's music, conceived as equally the observer, as the catalyst in this music, and harbinger of the idea that so often we think of beauty when in fact we should be thinking of destruction. The result, mixed in Reykjavík with Bedroom Community head Valgeir Sigurðsson, is a machined musical surface, evolved and refined, yet irrevocably damaged.

Curiously, darkness is expelled to the muddy sedge and a confusing irradiant glow permeates A U R O R A, where everything once wounded, remains fiercely animate and luminescent with charged destruction.

More information is available here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Glenn Jones has emerged as a clear leader in the new wave of American Primitive music for solo acoustic guitar. Many have mentioned his friendship with the late John Fahey, the genre's progenitor and demigod, but Glenn's music is truly all his own. His pensive sentimentality and playful spirit, not to mention his innovative technique, have become just as ingrained into the style’s DNA as any hallmarks of the original Takoma school. Welcomed Wherever I Go is a collection of live numbers, one featuring fellow guitarist Cian Nugent, and one forgotten tune recorded, speculatively, during the 2007 sessions for Jack Rose's Dr. Ragtime and His Pals.

"Island III" and "Against My Ruin" were both originally recorded for Glenn's 2007 album Against Which the Sea Continually Beats, and were subsequently played live as a medley. The recording that appears on Welcomed Wherever I Go was recorded in December of 2011 at the well-loved and now shuttered Brooklyn club Zebulon. "From A Lost Session" was a recording lost to time until Glenn discovered an unmarked CD-R in his archives, presumably during that classic session with Jack Rose. It is a particularly meditative track for Glenn, in a minor key with an incessant pedal tone not unlike Rose's pieces of the same era. The entire b-side of the release is occupied by a live take of "The Orca Grande Cement Factory at Victorville," a duet with similarly innovative guitarist Cian Nugent. Glenn will only play the song live in duet settings where the second musician has little to no preparation or coaching, letting them add to his instrumental musings, ignore them, or destroy them completely. Nugent's interpretation leans more toward the former.

Welcomed Wherever I Go is being released in a limited edition, vinyl-only format for Record Store Day 2014. Glenn will be doing limited touring in 2014, mostly in support of a new biography on John Fahey by Steve Lowenthal.

More information is available here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

In typically cryptic fashion, no information is provided about any of them...but here they are!

Alley Catss & S Olbricht

Ford Foster & William Watts

James Place

KETEV

Austin Cesear & Stefen Jós

Samples and (somewhat) more information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Psychic 9-5 Club marks the beginning of a new chapter for HTRK. It's an album that looks back on a time of sadness and struggle, and within that struggle they find hope and humour and love. It's Jonnine Standish and Nigel Yang's first album recorded entirely as a duo—former band member Sean Stewart died halfway through the recording of their last LP, 2011's Work (Work Work).

Though the record is instantly recognisable as HTRK—Standish's vocal delivery remains central to the band's sound, while the productions are typically lean and dubby—they've found ample room for exploration within this framework. Gone are the reverb-soaked guitar explorations of 2009's Marry Me Tonight and the fuzzy growls that ran through Work (Work Work). They've been replaced with something tender, velvety and polished. This is HTRK, but the flesh has been stripped from their sound, throwing the focus on naked arrangements and minimalist sound design.

The album was recorded at Blazer Sound Studios in New Mexico with Excepter's Nathan Corbin, who had previously directed the video clip for Work (Work, Work) cut "Bendin." Inviting a third party into their world was no easy decision, but in Corbin they found a kindred spirit. The LP was then refined and reworked in Australia at the turn of 2013, before the finishing touches were applied in New York during the summer.

Of all the themes that run through Psychic 9-5 Club, love is the most central. The word is laced throughout the album in lyrics and titles—love as a distraction, loving yourself, loving others. Standish's lyrics explore the complexities of sexuality and the body's reaction to personal loss, though there's room for wry humour—a constant through much of the best experimental Australian music of the past few decades.

Standish explores her vocal range fully—her husky spoken-word drawl remains, but we also hear her laugh and sing. Equally, Yang's exploratory production techniques—particularly his well-documented love of dub—are given room to shine. They dip headlong into some of the things that make humans tick—love, loss and desire—with the kind of integrity that has marked the band out from day one. Psychic 9-5 Club is truly an album for the body and for the soul.

Tracklist

01. Give it Up

02. Blue Sunshine

03. Feels like Love

04. Soul Sleep

05. Wet Dream

06. Love is Distraction

07. Chinatown Style

08. The Body You Deserve

Pre-order Psychic 9-5 Club here.

Read More