- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

Back in 2009, Duane Pitre curated a CD entitled The Harmonic Series that brought together an array of artists like Pauline Oliveros and Ellen Fullman for a collection of pieces composed for Just Intonation. Roughly a decade later, Pitre has returned with a considerably more ambitious second volume that enlists "six of the most important emerging voices of contemporary experimental music" for a triple LP extravaganza of longform Just Intonation pieces. To his credit, Pitre truly did assemble an impressive lineup for this release, as artists like Caterina Barbieri and Kali Malone are undeniably leading lights of the current vanguard. In fact, everybody here has a history of making great or provocative music, though I am not sure everyone was brimming with great ideas for a bombshell Just Intonation opus, as it seems like a daunting challenge for anyone attempting melodies. Given that, The Harmonic Series II is more of a fascinating mixed bag than a uniform triumph, though roughly half the artists managed to conjure up something that exceeded my expectations. And regardless of how well some pieces do or do not work, this collection has definitely expanded my idea of what is possible with Just Intonation.

Back in 2009, Duane Pitre curated a CD entitled The Harmonic Series that brought together an array of artists like Pauline Oliveros and Ellen Fullman for a collection of pieces composed for Just Intonation. Roughly a decade later, Pitre has returned with a considerably more ambitious second volume that enlists "six of the most important emerging voices of contemporary experimental music" for a triple LP extravaganza of longform Just Intonation pieces. To his credit, Pitre truly did assemble an impressive lineup for this release, as artists like Caterina Barbieri and Kali Malone are undeniably leading lights of the current vanguard. In fact, everybody here has a history of making great or provocative music, though I am not sure everyone was brimming with great ideas for a bombshell Just Intonation opus, as it seems like a daunting challenge for anyone attempting melodies. Given that, The Harmonic Series II is more of a fascinating mixed bag than a uniform triumph, though roughly half the artists managed to conjure up something that exceeded my expectations. And regardless of how well some pieces do or do not work, this collection has definitely expanded my idea of what is possible with Just Intonation.

Each of the six artists was given a full side of vinyl to work with, so each composition is roughly between 15-20 minutes long. The first side is devoted to Kali Malone's modest "Pipe Inversions," a duet between Malone (playing a "small pipe organ") and Isak Hedtjärn on bass clarinet. I was expecting Malone to contribute an album highlight, given how much thought went into the harmonies and frequencies of The Sacrificial Code, but "Pipe Inversions" is mostly just a slowly shifting series of chords with bleary harmonies centered around a more sonorous root. As such, its pleasures are more structural and subtly microtonal than some of the other pieces. Conversely, I was not sure how well Caterina Barbieri's strong melodic sensibility would handle this tuning challenge, but her closing "Firmamento" is one of the collection's strongest and most surprising pieces. Admittedly, Barbieri's melodicism did not come along for this trip, but her tense, neon-lit futurism did, as "Firmamento" is an enjoyably spacey and slow-burning drone epic. My favorite piece is Duane Pitre's own "Three for Rhodes," which combines an erratically heaving, herky-jerky pulse with a shimmering crystalline edge. I was also pleasantly surprised by Catherine Lamb's "Intersum," which goes against the grain to reduce Just Intonation harmonies to something akin to a ghostly supernatural fog drifting through a crackling and hissing backdrop of field recordings. The collection is rounded out by the gnarly, nightmarish strings and buzzing horror of Tashi Wada's "Midheaven (Alignment Mix)" and Byron Westbrook's kosmiche-sounding reverie of stammering, sweeping arpeggios ("Memory Phasings"). Aside from Barbieri's piece, which has a definite dynamic arc, the general theme of the album is extending a single interesting motif for the entire duration of a piece (albeit with plenty of small-scale dynamic and harmonic transformations along the way). As a result, how much I enjoy a piece within its first minute is generally a solid indicator of what I will think by the end. However, what I actually hear is just the tip of an iceberg of deeper compositional and conceptual themes, so listeners who are more invested in the details and mechanics of avant-garde composition will likely enjoy The Harmonic Series II on a deeper level than me. In any case, this is definitely an interesting and one-of-a-kind release. While some pieces are more instantly gratifying than others, each of the six artists involved found their own unique and inventive way to face the challenge and expand Just Intonation's historically constrained stylistic niche.

Samples:

- Kali Malone, "Pipe Inversions"

- Duane Pitre, "Three for Rhodes"

- Tashi Wada, "Midheaven (Alignment Mix)"

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This new EP is something of a sketchbook-like companion piece to Nayar's sublime debut album. More specifically, it is a collection of "sonic miniatures Nayar constructed from guitar loops . . . in the familiar comforts of her own bedroom," as well as a glimpse of what her raw material sounds like before it is processed and reshaped into "grander mutated compositions" like those of Our Hands Against the Dark. In theory, that should make Fragments something of a minor release, but these more simple and intimate pieces are often even better than those of Nayar's more formal work, albeit with the caveat that more than half of these pieces end in under two minutes (and the others do not stick around much longer). Nevertheless, Nayar is an incredibly gifted guitarist with a remarkably strong melodic sensibility and this album is quite a sustained hot streak of great (if ephemeral) ideas. As with her previous album, it is not hard to spot Nayar's influences—in fact, some pieces are even intended as homages to folks like Pat Metheny and Steve Reich. That said, the main touchstones I hear are more hook-minded contemporary artists like Mark McGuire and some classic Midwestern emo. That is always welcome stylistic terrain in my book, but the real beauty of Fragments lies in how often Nayar matches or surpasses her influences at their own games.

This new EP is something of a sketchbook-like companion piece to Nayar's sublime debut album. More specifically, it is a collection of "sonic miniatures Nayar constructed from guitar loops . . . in the familiar comforts of her own bedroom," as well as a glimpse of what her raw material sounds like before it is processed and reshaped into "grander mutated compositions" like those of Our Hands Against the Dark. In theory, that should make Fragments something of a minor release, but these more simple and intimate pieces are often even better than those of Nayar's more formal work, albeit with the caveat that more than half of these pieces end in under two minutes (and the others do not stick around much longer). Nevertheless, Nayar is an incredibly gifted guitarist with a remarkably strong melodic sensibility and this album is quite a sustained hot streak of great (if ephemeral) ideas. As with her previous album, it is not hard to spot Nayar's influences—in fact, some pieces are even intended as homages to folks like Pat Metheny and Steve Reich. That said, the main touchstones I hear are more hook-minded contemporary artists like Mark McGuire and some classic Midwestern emo. That is always welcome stylistic terrain in my book, but the real beauty of Fragments lies in how often Nayar matches or surpasses her influences at their own games.

The album begins in impressive fashion with two nearly perfect pieces in a row. The first, "memory as miniature," opens with chiming clean arpeggios before revealing a lead guitar melody that hits the breezy, laid back California vibe of prime McGuire before a synth-sounding chord progression pulls everything in a more bittersweet dreampop direction. Everything about it is wonderful, but I was especially struck by the beauty of the intricately chiming arpeggios that form its backdrop. The following "clarity," on the other hand, starts off sounding like a candidate for the best American Football song ever, as Nayar unleashes a gorgeously vibrant and ascending guitar melody. Much like its predecessor, however, "clarity" sticks tenaciously to its perfect opening theme and merely enhances it a bit with shimmering chords and some warm synth-like coloration in the periphery. Both of those pieces are prime examples of the compositional aesthetic that defines Fragments: each piece is essentially just an incredibly cool guitar hook playing out for a couple minutes before fading out or abruptly ending. While it lasts, each theme is subtly fleshed out to add emotional depth and a sense of harmonic development, yet each song is still essentially a single theme that is not allowed to blossom into a fully formed song. In theory, that should be exasperating ("aaaargh, why did you stop?!?"), but it is hard to complain when every too-soon ending only leads to yet another improbably beautiful new theme. In fact, there is not a single moment on Fragments that does not sound like an excerpt from a killer emo classic, an imaginary Slowdive song about to erupt, or the perfect soundtrack for a sun dappled summer drive along the California coast. While I dearly wish this EP was (much) longer, I would be hard pressed to hard to think of many other releases from this year that can match Fragments for sheer wall-to-wall greatness.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I believe this is the first formal collaboration between these two Sweden-based artists, but the pair have a long history together, as Mannerfelt's label released one of Lewis's early EPs (2014's Msuic). While I was not sure quite what to expect given the breadth of Mannerfelt's oeuvre and Lewis's continuous evolution, I was reasonably certain that this collaboration would be wonderful no matter what shape it took and I was not disappointed. The closest reference point for KLMNOPQ is probably Lewis's killer Ingrid EP, as nearly all of these five songs feature churning, blackened drones or murky, gnarled loops of some kind. The twist, however, is that Mannerfelt and Lewis take that roiling intensity in an unexpectedly playful direction without sacrificing much gravitas. The closing "Full of Piss and Vinegar" captures the duo at the height of their gleefully mischievous loop mangling, as it resembles a nightmarishly chopped-and-screwed mariachi band, yet this entire EP is filled with endearingly inventive and perversely anthemic variations of obsessively looping and psychotropic sound collage.

I believe this is the first formal collaboration between these two Sweden-based artists, but the pair have a long history together, as Mannerfelt's label released one of Lewis's early EPs (2014's Msuic). While I was not sure quite what to expect given the breadth of Mannerfelt's oeuvre and Lewis's continuous evolution, I was reasonably certain that this collaboration would be wonderful no matter what shape it took and I was not disappointed. The closest reference point for KLMNOPQ is probably Lewis's killer Ingrid EP, as nearly all of these five songs feature churning, blackened drones or murky, gnarled loops of some kind. The twist, however, is that Mannerfelt and Lewis take that roiling intensity in an unexpectedly playful direction without sacrificing much gravitas. The closing "Full of Piss and Vinegar" captures the duo at the height of their gleefully mischievous loop mangling, as it resembles a nightmarishly chopped-and-screwed mariachi band, yet this entire EP is filled with endearingly inventive and perversely anthemic variations of obsessively looping and psychotropic sound collage.

The opening "Sell Art" nicely sets the tone for the entire EP, as blown-out, heaving drones slowly churn beneath a trilling hook that sounds like a repurposed mariachi trumpet melody. The central melody sounds pleasingly frayed and ghostly like a ravaged tape loop, but the more impressive feat is how Lewis and Mannerfelt seamlessly transformed festive traditional music into something resembling a techno anthem in the throes of a bad break-up. It is quite a neat trick, as there is an underlying playfulness and dark sense of humor, but the result is legitimately poignant and weirdly haunting nonetheless. Another theme in "Sell Art" that recurs throughout the album is the duo's love of obsessively repeating and layered loops, which has long been a realm in which Lewis excels. In the second piece, "My Clementine Is Making Paella Tonight," a repeating chord swell holds the focus as a steadily intensifying undercurrent brings a relentless sense of forward motion and brooding urgency. Near the end, the consistent rhythm dissolves to make room for more freeform percussion, resulting in something that sounds like Z'ev pounding plastic oil drums along with a Fossil Aerosol Mining Project album. Next, "Styrofoam Tone" amusingly wrongfoots me again with something that sounds like the vocal hook of some ‘90s dance hit chopped apart and rebuilt into a seething and hiss-soaked nightmare. The following "You Need to Be Kind" also sounds like an isolated pop fragment telescoped into an unintended new soundworld, albeit one taking a churning, fuzzed-out, and spacey ambient bent. The EP then closes with the aforementioned "Piss and Vinegar," which sounds like a pre-bullfight trumpet fanfare frozen in suspended animation, then erratically allowed to play out a bit more before it locks into a different fluttering loop. From there, it only gets increasingly disorienting and weird, calling to mind Throbbing Gristle DJing a Mexican street festival and doing their best to get fired. My sole caveat with this EP is that every song feels like layers of loops manipulated with real-time mixing as opposed to more formal compositions, but most Klara Lewis fans (myself included) will be more than happy to hear a bunch of great loops being expertly manipulated and imaginatively juxtaposed.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I am kicking myself for not catching up on this post-Lost Trail project sooner, as the alarmingly prolific Zachary and Denny Corsa have a long history of making great music and they may very well have reached their zenith with this latest chapter in their collaborative evolution. That said, Nonconnah is something more than just a husband-and-wife duo, as the Corsas describes the endeavor as a "Memphis dronegaze collective." That is a bit of an understatement, given the far-reaching and eclectic array of luminaries that have turned up on past Nonconnah albums, but the heart of the project is the mingling of Zachary's guitar playing with Denny's field recordings. The "dronegaze" part of "dronegaze collective" is a bit of an understatement too, as it mostly just describes Zachary's sublime guitar aesthetic. Sadly, I cannot think of a glib combination of words that better encompasses what this first vinyl release from the project actually sounds like, but my best attempt is that it sounds like some shoegaze guitar god dropped by the GRM for a series of ecstatic-sounding improvisations with some brilliant musique concrète enthusiast, then wove all the coolest parts together into achingly beautiful and intricately layered sound collages. When Denny and Zachary are at their best, they are damn near untouchable, as I can think of no one else who so organically blurs together naked beauty, go-for-broke psychotropic brilliance, and immersive textural richness.

The vinyl version of the album ostensibly consists of four separate twelve-minute pieces, but each of those is further delineated into five separate movements, which makes for quite an unusual structure (the album feels like series of vignettes constantly segueing into different themes). Similarly, it is damn hard to figure out who is doing what on any given piece, as Zachary is credited with quite a wide array of sounds (noise, tapes, field recordings) that blur the lines between his contributions and Denny's. Guest collaborators Owen Pallett (strings) and Jenn Taiga (synths) are a bit easier to find in the mix, but individual performances are largely irrelevant, as one prominent feature of this album is its tendency to regularly blossom into complexly layered and rapturous "wall of sound" crescendos. In those delirious moments, it can sound like a dozen tapes playing at varying speeds in an abstract symphony of swooning, frayed beauty. Given that the album is essentially twenty individual pieces of varying lengths that bleed into one another, figuring out which title those moments of sublime, ecstatic transcendence correspond to is largely a fool's errand. The crucial thing is merely that there are plenty of them and that the more understated moments that bridge them are often wonderfully hallucinatory or strikingly lovely as well. For example, in the first side's "II. Changed In Autumn's Feral Depths" alone, the foursome pass through a dreamily warped and angelic choral passage, an interlude of chirping birds, an eerily poignant spoken word sample, a bittersweetly devastating string theme, and a gorgeously warbling and shivering climax of backwards guitar loops. Listening to it now, it feels like an absolute tour de force of distinctive and absolutely beguiling passages and it probably is not even my favorite of the album's four numbered sections: every single damn piece is a highlight. The digital version also includes two brief bonus tracks identified as excerpts and they are similarly brilliant (especially the roiling and roaring tape loop pile-up "Summer Sparkler Dream Cartridge"). Admittedly, some listeners might be a bit exasperated by the album's unusual structure and may find themselves wishing that certain passages had been expanded into fully formed, stand-alone compositions. Normally I would feel that way too, but the Corsas are making some of the most sublime, absorbing, and vividly textured music on earth right now, so any way they feel like presenting it is just fine by me. This is easily one of the finest albums that I have heard this year.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

A duo between California artists Victoria Shen and Bryan Day (by way of Nebraska), Error Theft Disco is noise in its purist sense. A disorienting blend of electronics, distortion, and found sounds that never settles down from the first few seconds, the constant flow gives the tape a captivating sense of inertia that functions well in the loud harsh noise vein as well as it does the nuanced, complex sound art one.

A duo between California artists Victoria Shen and Bryan Day (by way of Nebraska), Error Theft Disco is noise in its purist sense. A disorienting blend of electronics, distortion, and found sounds that never settles down from the first few seconds, the constant flow gives the tape a captivating sense of inertia that functions well in the loud harsh noise vein as well as it does the nuanced, complex sound art one.

This is one of those tapes where there is no sense in trying to deconstruct instrumentation or sound design techniques, because there is simply too much going on. Which is made all the more difficult given that both Shen and Day build many of their own instruments as well. Right from the squeaky, waxy noises that begin “Ala Modem in Modernity” the duo throw a bit of everything out there. Crunchy, almost rhythms collide with shrill outbursts, and modular electronics all propel the piece along.  This kinematic approach barrels into "Brutal Hygene," which is all chirpy sounds, found voices, and heavy bass thumps.

The third piece on the first side, "Harrier Spray," is just as active, but does feature the duo allowing some of the passages to breath a bit. Comparably more loop-ish in nature, there is a somewhat more noteworthy sense of structure amidst the distorted pulsations. "Mouthsh" covers the entire second half of the tape, and also features a bit more restraint from the two. There are still large amounts of subsonic bass and shrill electronic beeps and tones, but overall there is a slower creep that nudges along the overdriven electronics. There are a healthy proportion of extreme frequencies to be found, but never does it feel oppressive or painful.

Pay Dirt’s Error Theft Disco is a noise tape in its most distilled form. There is little that is identifiable and there does not seem to be any specific theme running through the four pieces. However, a great noise tape never needs any of these things, and that is certainly the case here. It is a hyperactive burst that never relents, and with so much activity happening from second to second, the depth is just as engaging as the chaos.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

Described as "free chamber music in feedback environments," this massive double CD from New York based artist Bob Bellerue is a perfect blend of structure, improvisation, and chance. Based around rough compositional structures, but left wide open to improvisation, the five instrumentalists, along with Bellerue helming electronics and production, create a massive noise that distinctly reflects the time, place, and conditions in which this material was recorded.

Described as "free chamber music in feedback environments," this massive double CD from New York based artist Bob Bellerue is a perfect blend of structure, improvisation, and chance. Based around rough compositional structures, but left wide open to improvisation, the five instrumentalists, along with Bellerue helming electronics and production, create a massive noise that distinctly reflects the time, place, and conditions in which this material was recorded.

Recording in two sessions on July 29 and 30 of 2020 at the First Unitarian Congregational Society of Brooklyn, the physical space in which the performance occurred works like another piece of the ensemble. The players, including saxophonist Ed Bear, double bassists Brandon Lopez and Luke Stewart, violinist Gabby Fluke-ogul, and viola/organist Jessica Pavone all appear together on three of the six pieces (two of them are Bellerue solo, and one features just him and Pavone on organ), but even in these three works, it is often hard to discern specific players.

The expansive, bleak "The Longest Year" does have some identifiable buzzing strings from Fluke-Mogul and Pavone, but the space and production give it an unnatural, otherworldly color to the sound. The scraping and grinding sounds build into dense clusters not unlike some of Hermann Nitsch's early scores. "Bass Feedback" is, unsurprisingly, bass heavy, but also has some painfully shrill sections as well. Instrumentation is obvious at times, but the focus is on the abstract tones. The title piece shifts from harsh, distorted sax to scraped strings and a nasal insect buzz, later bouncing between horror film strings and dense noise walls.

“Organ Feedback,” featuring just Bellerue and Pavone, is the closest to melody that Radioactive Desire gets. At times almost synth-like, the layered tones blend together beautifully through the rather steady overall dynamic. On the other hand, Bellerue's two solo pieces are far closer to harsh noise than anything else. “Empty Feedback,” which is just room noise and unattended instruments, builds from hissy buzzes to machinery like hums to painfully shrill feedback. Everything from stabbing high frequencies to dense steady walls of sound appear. The near 40-minute conclusion "Metal Gambuh" is just that: a suling gambuh flute, metal, and feedback. Bathed in heavy natural reverb, it is a violent outburst of frustration, with oppressive sub bass underscoring the fuzzy crackles and droning noise.

Radioactive Desire is by its very nature an intense work. Recorded in a massive space, in oppressive summer temperatures after a long stretch of lockdown, and spreading out over two hours, there is a lot to absorb. With Bellerue leading the five performers in their improvisation, the intensity of this work is not just in the composition, but in the performance, as well as the space in which it was recorded. Everything is huge, but with such nuance that it never becomes too much to take in, with Bellerue's guiding hand beautifully guiding the material through all its disparate facets.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

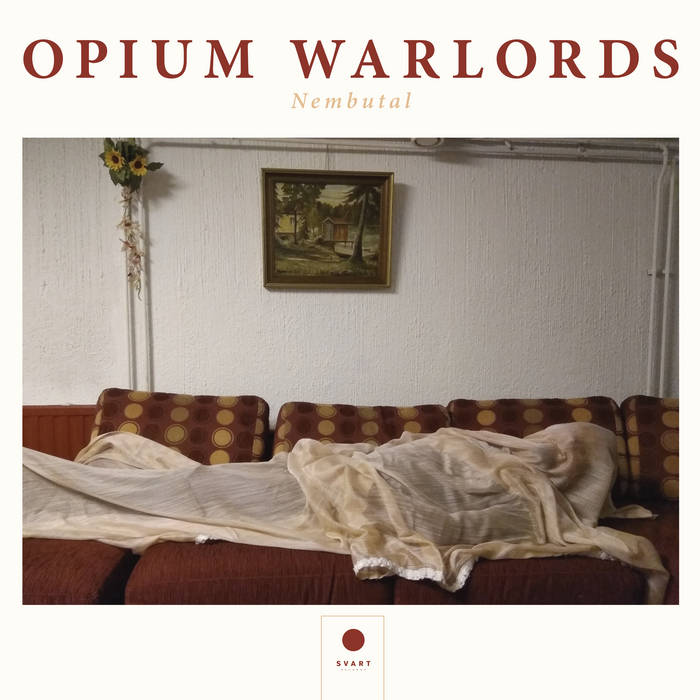

In 2010, the Opium Warlords’ MySpace page claimed they sound like "a bad Bolivian Metal band practicing a riff.” Fair enough, but at times their ponderous, doom-laden, brooding, drone-metal shows signs of being more than just another fatberg clogging the sewers of musical culture. My introduction to the group was Live At Colonia Dignidad. Nembutal is a better produced recording, with more variation in speaking, singing, and what sounds like movie dialogue samples. The pest of cliched lyrics such as on “Destroyer of Filth,” is laughable and disappointing, because at other times the words are mysterious and intriguing, sung powerfully and with room to breathe. In those moments, allied with portentous guitar work and a contemplative tempo, Nembutal is nicely out of sync with the flashy haste of modern life.

In 2010, the Opium Warlords’ MySpace page claimed they sound like "a bad Bolivian Metal band practicing a riff.” Fair enough, but at times their ponderous, doom-laden, brooding, drone-metal shows signs of being more than just another fatberg clogging the sewers of musical culture. My introduction to the group was Live At Colonia Dignidad. Nembutal is a better produced recording, with more variation in speaking, singing, and what sounds like movie dialogue samples. The pest of cliched lyrics such as on “Destroyer of Filth,” is laughable and disappointing, because at other times the words are mysterious and intriguing, sung powerfully and with room to breathe. In those moments, allied with portentous guitar work and a contemplative tempo, Nembutal is nicely out of sync with the flashy haste of modern life.

To be honest, my girlfriend went away for a few days, and I decided to spin a couple of albums overlooked in 2020. Alabaster dePlume’s To Cy & Lee: Instrumentals Vol. 1 was a great listen, somewhere between the pastoral hum of Anthony Phillips and the clear, sparse jazz of Jeff Parker’s Suite For Max Brown. It has now been picked up by the same label as Angel Bat Dawid. No such liftoff as yet for Opium Warlords, although like tripping into a predictably cartoonish puddle of lumpy brown medieval sludge, they do make for a bracing contrast. The album starts and ends with a couple of monolithic tracks, but “Threshold of Your Womb” is as strangely hypnotic as being attacked by a tribe wielding gamelan gongs and a fuzz pedal. Two creepy pieces about women suffering a tragic fate are also good, but I’d have preferred if one or both had a male victim. If you call yourself Opium Warlords the subject matter is going to be unflinchingly dark, methinks, but the flashes of subtlety here - guitar tone, song pacing, running order- hint at greater promise. For example, the contrasting guitar work of “Solar Anus” is great. It is as if they are simultaneously not trying and trying too hard.

As detailed in his book 45, Bill Drummond (of Big in Japan, The KLF and more) once made up an entire Finnish underground scene for his own purposes, and recorded singles by these imaginary groups (The Daytonas, Gormenghast, The Blizzard King, Aurora Borealis, and The Fuckers). But he never came up with a name as good as Opium Warlords. The group is the solo project of Sami Albert “Witchfinder” Hynninen, who has added the witch-finding part to his title since I last looked. He has not changed his sound a great deal, though, and I am not changing my opinion too much. For the Opium Warlords to broaden their appeal, they need to continue to refine their sound and improve their lyrics. Maybe also listen to some Chrome. Yet, perhaps the "Bolivian metal" self-mocking and the daft mumbling and growling is a ruse; after all, it is said that the greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was to make us believe he doesn't exist. And the name is marvelous; conjuring histories of deceit, greed, and war, the British in China, the French in Vietnam, the heroin labs of Marseille, the Golden Route, the release of Lucky Luciano and the role of the Mafia in assisting the Allies in opening a second front in WWII, Fidel Castro’s exploding cigar, Oliver North’s covert exploits in Colombia and Iran, CIA tolerance for Afghan opium production and export, and the alleged payment of $43 million to the Taliban government for crushing opium production, just months before the US invasion of Afghanistan with the support of the Afghan opium warlords.*

*Ed Felien: The Big Payoff

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

My relationship with Ben Chasny's discography has always been a hit-or-miss one, as some of his albums are very much Not For Me, yet I can think of few other artists who are as intensely committed to endlessly evolving and trying out bold new ideas. This latest release is a prime example of that, as The Veiled Sea can be glibly described as "the album where Ben Chasny unleashes some absolutely face-melting shredfests." In characteristically open-minded fashion, Chasny drew inspiration for this album from an extremely unusual source: "'80s American pop shredder" Steve Stevens, who I knew primarily as Billy Idol's guitarist, but who others may recall from the theme from Top Gun (or Michael Jackson's "Dirty Diana"). Given that Top Gun and contemporary psychedelia seem like a truly deranged collision of aesthetics to bring together, I was a bit apprehensive about this release and expected an audaciously over-the-top album that I would probably only listen to once. Instead, it was something considerably more soulful and compelling than I ever expected, as Chasny swings for the fences on a couple of songs and connects beautifully, crafting a pair of the most perfect pieces of his entire career. There is also a wild Faust cover and some more ambient-minded pieces rounding out the album to varying degrees of success, but the only crucial thing to know about The Veiled Sea is that "Last Station, Veiled Sea" may very well be the "must hear" song of the year in underground music circles.

My relationship with Ben Chasny's discography has always been a hit-or-miss one, as some of his albums are very much Not For Me, yet I can think of few other artists who are as intensely committed to endlessly evolving and trying out bold new ideas. This latest release is a prime example of that, as The Veiled Sea can be glibly described as "the album where Ben Chasny unleashes some absolutely face-melting shredfests." In characteristically open-minded fashion, Chasny drew inspiration for this album from an extremely unusual source: "'80s American pop shredder" Steve Stevens, who I knew primarily as Billy Idol's guitarist, but who others may recall from the theme from Top Gun (or Michael Jackson's "Dirty Diana"). Given that Top Gun and contemporary psychedelia seem like a truly deranged collision of aesthetics to bring together, I was a bit apprehensive about this release and expected an audaciously over-the-top album that I would probably only listen to once. Instead, it was something considerably more soulful and compelling than I ever expected, as Chasny swings for the fences on a couple of songs and connects beautifully, crafting a pair of the most perfect pieces of his entire career. There is also a wild Faust cover and some more ambient-minded pieces rounding out the album to varying degrees of success, but the only crucial thing to know about The Veiled Sea is that "Last Station, Veiled Sea" may very well be the "must hear" song of the year in underground music circles.

There are technically six songs on The Veiled Sea, but the party does not begin in earnest until the third piece, "All That They Left You." To my ears, it sounds like Carter Tutti Void and A Certain Ratio are jamming with Appetite for Destruction-era Slash, as it is a feast of jangly post-punk guitars, brooding industrial thump, and indulgently fiery hard-rock shredding. There is a catchy song lurking in there too, as the soloing frequently breaks to make room for a haunting, processed-sounding vocal hook (Chasny sounds a bit like a sultry but lovesick robot). For the most part, though, it is simply Chasny ripping shit up on his guitar over a cool, heavy groove and it rules. A brief and likable interlude of tender piano ambiance follows ("Old Dawn"), then the album hits its zenith with "Last Station, Veiled Sea," which unexpectedly resembles This Mortal Coil at first (languorous drones, vaguely androgynous-sounding vocals, a dreamily melancholy mood, etc.). After about three minutes, however, Chasny unleashes an absolute supernova of a guitar solo that is equal parts movingly gorgeous and viscerally violent (it features plenty of Orcutt-esque scrabbling, slashing, and gnarled flourishes). Sadly, it only lasts about ten minutes, but Chasny sounds absolutely possessed and I am sure he could have gone on for another half hour with absolutely no dip at all in soulful intensity at all. Not much could follow such god-tier brilliance, but the surprise Faust cover that closes the album is quite satisfying nonetheless. The bouncy, playful original version of "J'ai Mal aux Dents" sounds like a bunch of mischievous art weirdos jamming on a fake Velvet Underground song. In Chasny's hands, however, it becomes a heavier, more trancelike juggernaut, as he uses a tumbling drum pattern and chanting backing vocals as a propulsive backdrop for a roiling, spacey guitar solo. It is quite a delight, but the main reasons to hear this album are the twin highlights of "All That They Left You" and "Last Station, Veiled Sea," which unavoidably eclipse everything around them.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I was not familiar with this Norwegian artist until a few weeks ago, but I find that just about everything on Ireland's wonderfully weird and adventurous Fort Evil Fruit is worth hearing. That seems to be doubly true when an album also features amusingly Cronenbergian child art and a droll Coil reference. Unsurprisingly, Cronenberg and Coil are among Br√∏rby's many influences for this album, but they thankfully do not surface in derivative or unimaginative ways. Instead, Constant Shallowness Leads to Body Horror is an unexpectedly amiable "love letter to taste-defining early influences" presented as a flickering fever dream of Br√∏rby's fond childhood memories of grainy VHS films, surreal late night television commercials, videogames with friends, and the thrill of discovering underground music's weird and shadowy fringes. All of that predictably sounds great to me, but what makes this album even better is that Br√∏rby proves remarkably adept at filtering all of that into a focused, distinctive, and oft-beautiful vision. In its own bizarre way, Constant Shallowness is an outsider pop album, as the heart of these pieces is Br√∏rby's strong melodic sensibility and a real knack for cool percussion. That alone would be enough to make this a strong release, but Br√∏rby went one step further and enveloped his warm, ramshackle, and endearingly lovely pop vignettes in a stammering, obsessive, and phantasmagoric swirl of vividly multidimensional mindfuckery. He is exceptionally good at that last bit, making this one hell of a immersive album.

I was not familiar with this Norwegian artist until a few weeks ago, but I find that just about everything on Ireland's wonderfully weird and adventurous Fort Evil Fruit is worth hearing. That seems to be doubly true when an album also features amusingly Cronenbergian child art and a droll Coil reference. Unsurprisingly, Cronenberg and Coil are among Br√∏rby's many influences for this album, but they thankfully do not surface in derivative or unimaginative ways. Instead, Constant Shallowness Leads to Body Horror is an unexpectedly amiable "love letter to taste-defining early influences" presented as a flickering fever dream of Br√∏rby's fond childhood memories of grainy VHS films, surreal late night television commercials, videogames with friends, and the thrill of discovering underground music's weird and shadowy fringes. All of that predictably sounds great to me, but what makes this album even better is that Br√∏rby proves remarkably adept at filtering all of that into a focused, distinctive, and oft-beautiful vision. In its own bizarre way, Constant Shallowness is an outsider pop album, as the heart of these pieces is Br√∏rby's strong melodic sensibility and a real knack for cool percussion. That alone would be enough to make this a strong release, but Br√∏rby went one step further and enveloped his warm, ramshackle, and endearingly lovely pop vignettes in a stammering, obsessive, and phantasmagoric swirl of vividly multidimensional mindfuckery. He is exceptionally good at that last bit, making this one hell of a immersive album.

In an amusingly valiant commitment to thematic consistency, the album opens with a bit of "constant shallowness" and closes with a small helping of "body horror." That opening piece ("Baby, You’re Disharmonic") is one of my favorites, as an obsessively repeating and erratically transforming commercial snippet laments hair care woes over a woozy and hallucinatory strain of hypnagogic synth pop. In a broad sense, it sounds like LA Vampires chopped and screwed an Enya/Negativland mash-up, yet it is considerably more haunting and poignant than such a playful collision of aesthetics would suggest. Some more overt nods to other artists appear later, such as the Tim Hecker-esque roiling, distorted majesty of "Imaginary Scene II" or the Oval-esque skipping loops of "Still Warm." To some degree, that makes those pieces a bit less distinctive than others, yet it mostly seems like Brørby learned Hecker's and Popp's best tricks and promptly set about using them in his own way. In any case, "Imaginary Scene II" is unquestionably one of the album's many highlights, as the twinkling piano melody buried in the churning maelstrom is an achingly lovely touch. For the most part, however, I prefer the pieces with beats, as one of the album's greatest pleasures lies in how expertly Brørby manages to transform his simple, warm, and subtly beautiful melodic themes into something wonderfully weird with inventive percussion and vivid intrusions of layered, jabbering psychedelia. The best of that side of Brørby's vision is probably "Dungeon Crawlers Leveling Up," which marries thick, spacey synths with a lurching groove and a host of crunching, crackling, and squealing industrial textures. Elsewhere, "I'm Sorry..." sounds like a jackhammering construction project distantly unfolding in a blissful cloudlike heaven of soft-focus chords and chirping birds, while "Pre-Sports..." sounds like a funky live drummer and a distressed tape of a techno anthem emerging together from a churning nightmare. If there is anything that resembles Coil at all here, it is the smeared, twilit atmosphere of "See No Evil Hear All Evil," but even that ultimately winds up with a simmering, sultry groove. It is admittedly a strong piece, but so is absolutely everything else on this wonderful album.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

Sarah Lipstate's latest opus enigmatically borrows its title from a disorder in which those afflicted lose the ability to create mental imagery and associations (it literally translates as "without imagination"). If there is a polar opposite of that disorder, there is a strong probability that Lipstate has it, as Aphantasia is an absolute tour de force of imaginative, vividly realized visions. In fact, there are twenty-two such self-contained visions on the album and very few of them stretch beyond a minute or two in length. That can be a bit exasperating at times, as the most wonderful ideas are often some of the most ephemeral, but the sheer volume of killer motifs on display could have been the framework for four albums of great fully formed songs rather than one dazzling array of brief vignettes. That unusual album structure was entirely by design, of course, as Lipstate viewed each song as a "a short sharp flash," further noting that "if her usual process brought about cinematic results, these were something new – something swift and intriguing." The "something new" is that the album is intended as something akin to a poetry collection, and it succeeds admirably in that light while still remaining extremely damn cinematic regardless. The fragmentary nature of this album will likely garner a somewhat polarized response from fans, but I doubt that anyone will question whether Lipstate is at the height of her creative powers right now.

Sarah Lipstate's latest opus enigmatically borrows its title from a disorder in which those afflicted lose the ability to create mental imagery and associations (it literally translates as "without imagination"). If there is a polar opposite of that disorder, there is a strong probability that Lipstate has it, as Aphantasia is an absolute tour de force of imaginative, vividly realized visions. In fact, there are twenty-two such self-contained visions on the album and very few of them stretch beyond a minute or two in length. That can be a bit exasperating at times, as the most wonderful ideas are often some of the most ephemeral, but the sheer volume of killer motifs on display could have been the framework for four albums of great fully formed songs rather than one dazzling array of brief vignettes. That unusual album structure was entirely by design, of course, as Lipstate viewed each song as a "a short sharp flash," further noting that "if her usual process brought about cinematic results, these were something new – something swift and intriguing." The "something new" is that the album is intended as something akin to a poetry collection, and it succeeds admirably in that light while still remaining extremely damn cinematic regardless. The fragmentary nature of this album will likely garner a somewhat polarized response from fans, but I doubt that anyone will question whether Lipstate is at the height of her creative powers right now.

The best way to view Aphantasia is as an impressionist funhouse in which each door reveals a fleeting glimpse of something wonderful (or disturbing) that quickly dissolves to make way for the next vision. The darkest vignettes mostly arrive early on, as "Rune (for Silent Guitar)" feels like the soundtrack to a psychedelic folk horror film, while smeared and curdled synth tones of "A Valley of Snakes" call to mind a lurid, art-damaged giallo classic. Elsewhere, the more substantial "The Haunted Man" feels like a great post-rock band adding quietly smoldering accompaniment to an eerily lit Dario Argento film. The darkness resurfaces a few more times near end of the album as well, as "The Gatherer" feels like a creepy, feedback-ravaged faerie tale, while "Night/Heist" briefly resembles a nightmarishly Lynchian rockabilly band. In between and around those more haunted moments, the remaining seventeen songs are like a highlight reel of imaginary dreampop, 4AD, and goth-rock classics from the late '80s and early '90s (though they seldom make it very far beyond the opening hook). The best pieces sound like Lipstate channeled some beloved band from the shoegaze/dreampop golden age, made some sort of ingenious and welcome improvement, isolated the best part, then quickly moved onto the next challenge. In "to love / dream you," for example, she evokes a more tender and burbling Lovesliescrushing, then later repeats that same feat even more impressively with "Annalemma." Elsewhere, "Vanishing" sounds like the achingly gorgeous coda of an imagined Slowdive masterpiece, while "33" feels like a glimpse of an absolutely sublime lost Durutti Column classic. At other times, Lipstate conjures a more psych-minded Bauhaus or Santo & Johnny lost in a phantasmagoric fever dream. Throughout it all, she unleashes a characteristically dazzling host of killer effects and cool textures. I expected that part, obviously, but did not expect her to casually toss off so many gorgeous melodic themes as well. Admittedly, part of me wishes there was at least one perfect, fully realized single akin to "Deep Shelter" here, but the sheer volume of great ideas on display makes for a wonderfully kaleidoscopic and immersive whole.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

Room40 continues its campaign to celebrate this Argentinian composer's underheard body of work with a second volume of selected pieces very different from the voice- and field recording-centric fare of last year's Echos+. That said, Canto+ does share its predecessor's curatorial aesthetic of combining pieces from her more prolific ‘70s heyday with more recent work and the differing eras sit quite comfortably together. To some degree, Canto+ feels like a very synth-driven album, as there are plenty of modular synth sounds and textures fluttering and chirping around, but nailing down an overarching vision that unites these pieces is surprisingly elusive, as every piece is full of unexpected and surreal detours into unfamiliar terrain. In fact, that elusiveness is arguably what most defines Ferreyra's work the most here, as a major recurring theme of Canto+ is the organically fluid and oft-surprising way in which these pieces evolve: they never linger very long in familiar melodic or structural territory, yet they always wind up getting somewhere unique and compelling. Of the two Room40 collections, I still prefer Echos+ as a whole, but a piece like "Canto del loco (Mad Man's Song)" would probably be a highlight on just about any release (Ferreyra-related or otherwise). Ferreyra's vision can admittedly be challenging at times, but the rewards make it a journey well worth taking.

Room40 continues its campaign to celebrate this Argentinian composer's underheard body of work with a second volume of selected pieces very different from the voice- and field recording-centric fare of last year's Echos+. That said, Canto+ does share its predecessor's curatorial aesthetic of combining pieces from her more prolific ‘70s heyday with more recent work and the differing eras sit quite comfortably together. To some degree, Canto+ feels like a very synth-driven album, as there are plenty of modular synth sounds and textures fluttering and chirping around, but nailing down an overarching vision that unites these pieces is surprisingly elusive, as every piece is full of unexpected and surreal detours into unfamiliar terrain. In fact, that elusiveness is arguably what most defines Ferreyra's work the most here, as a major recurring theme of Canto+ is the organically fluid and oft-surprising way in which these pieces evolve: they never linger very long in familiar melodic or structural territory, yet they always wind up getting somewhere unique and compelling. Of the two Room40 collections, I still prefer Echos+ as a whole, but a piece like "Canto del loco (Mad Man's Song)" would probably be a highlight on just about any release (Ferreyra-related or otherwise). Ferreyra's vision can admittedly be challenging at times, but the rewards make it a journey well worth taking.

It is always a pleasant surprise when the best song on an album is also the longest and that is the case with the aforementioned "Canto del loco." Happily, it delivers on its provocative title too, resembling the sort of hallucinatory tour de force that could only be brought to life by a mad genius, as Ferreyra alternately conjures a rubbery and rhythmic chorus of psychedelic frogs, an enchanted night meadow of flickering fireflies, an eruption of spectral banshees, and several other equally bizarre scenes over the course of the piece's twelve minutes. Sometimes it also sounds like disjointedly alien and gelatinous synth blatting, but just about everything Ferreyra unleashes feels wildly unique, eerily beautiful, or unnervingly otherworldly. It is definitely a ride that I did not want to end. Fortunately, the pieces that follow are compellingly weird too (if somewhat less unrelentingly dazzling). On "Pas de 3…ou plus," a hushed and hissing swirl of voices turns into something akin to an asteroid field before resolving into a dripping, gurgling, and echoing coda of liquid sounds. Then the following "Jingle Bayle's" sounds like a scene in a whimsically haunted clocktower that blossoms into a full-on Lovecraftian nightmare. I believe both of those pieces are more recent ones (composed nearly four decades after 1974's "Canto del loco"), but "Etude aux sons flegmatiques" returns to the '70s for another fine extended piece. It initially sounds like a deep bell tone is supernaturally transforming into a lysergically bleary haze of shifting feedback, but ultimately blossoms into something resembling a simmering and understated noise guitar performance of amplified squeaks, creaks, and whines (I bet there is probably a Kevin Drumm album in a similar vein lurking somewhere in his vast discography). The final piece then shifts gears yet again, as "Au revoir l’Ami" calls to mind ghosts flitting in and out of the shadows during an electroacoustic improv session in an abandoned and partially submerged factory. All five pieces are impressive feats of mindfuckery, but I was most struck by the twisting and turning trajectories they each took to get there. Beatriz Ferreyra is a composer like no other, as this album is like exploring a funhouse in which a new trapdoor is always poised to drop me somewhere even more unfamiliar.

Samples can be found here.

Read More