- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

For their fourth studio album, this Texan combo retains their guitar-centric post-rock approach but expands more into abstraction and dissonance amongst these nine instrumental compositions. Shades of shoegaze and electronic ambient pepper the pieces, but the TWDY do an exceptional job at making sure the record is one that is impossible to easily categorize.

For their fourth studio album, this Texan combo retains their guitar-centric post-rock approach but expands more into abstraction and dissonance amongst these nine instrumental compositions. Shades of shoegaze and electronic ambient pepper the pieces, but the TWDY do an exceptional job at making sure the record is one that is impossible to easily categorize.

The drastic within-song changes that appear on this album are the moments that I found particularly fascinating."New Topia" begins with gentle guitar melodies from Jeremy Galindo and Chris King, accented by subtle electronics before bursting open at the midway point.The gentler stuff is still there, but overpowered by rapid-fire drumming and heavier guitar sounds.The band’s way of transition from peaceful to explosive while still maintaining a consistent composition is expertly accomplished.

That dynamic shift appears in a few other places throughout the album as well:the snappy drum loops of "Invitation" might at first contrast with the gentle guitar passages, but throughout an all too short four minutes the band builds layer by layer into a dramatic coda.This makes for a climax that retains beauty from before, but with an unparalleled force and intensity.That transition from gentle to heavy also is apparent on "Serpent Mound," although its change from fuzzy guitar and tasteful overdriven noise into slowly shambling noise rock is not quite as dramatic.

This change in structure is not a gimmick, nor is it overused on the album.For its first half, "Dustism" has the band mixing dubby echoed drums and insistent cymbals with quiet guitar, with a just slightly out of tune quality that is reminiscent of recent Jesu works before the band uses the second half to shift up the rhythm.It is comparably a minor variation, but one that goes a long way within the piece and is extremely effective in keeping it interesting.The albums conclusion, "God's Teeth" is the most expansive, with the band using less of the fuzzy ambient haze that drenches most of the album.Building from gentle and delicate guitar sounds, much of the piece is slow and pensive.In its closing minute, everything decays to a fuzzy, noisy mass that could almost be a tape melting.

This Will Destroy You have never been known for overly subdued works, and Another Language continues their tradition of grandiose, yet tasteful cinematic works.Even with all of this drama injected into four to seven minute segments, the subtlety and nuance of their songwriting results in a record that succeeds on multiple levels, not just in sheer force, but also in the tiny details that surround the bombastic moments.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

A spate of vinyl reissues has brought welcome attention to Family Fodder more than 30 years after they formed, and their eclectic music sounds as engagingly fresh, naive, and wise, as ever.

A spate of vinyl reissues has brought welcome attention to Family Fodder more than 30 years after they formed, and their eclectic music sounds as engagingly fresh, naive, and wise, as ever.

Legend has it that Family Fodder frequently used a parlor game approach to songwriting. This technique sought to encourage spontaneity and happy accidents. Thus, after someone had spent five minutes on a lyric, it would be passed to the person on the right. This would continue, with responsibility for musical direction similarly shifting, until a piece was complete. Then it would be recorded with no revision. Whether or not this actually occurred on a regular basis, the group’s Euro-punk-folk, Afro-psychedelia, communal, voice-centered music is a remarkably consistent and endearing hybrid.

Just Love Songs is a limited edition, vinyl-only, release, which strips 11 of the group’s tunes down to their loveliest state. The first two of these give a clear indication of the variety in this collection. The sawing, cello-led, gnawing, dirge love mantra of "The Onliest Thing" gives way to breezy nostalgia on "Hippy Bus To Spain" (which resembles how I imagine Young Marble Giants might sound if they were stuck in a phase obsessed equally by Tropicalia and Cliff Richard’s Summer Holiday movie). Fuzz guitar is interjected here and there, most splendidly on end track "Don’t Get Me High" which might be the most polite sounding psychedelic track ever. "Primeval Pony" features the very alluring singing of Darlini Sing-Kaul, adult daughter of original Fodder vocalist Dominque Levillan, and sounds happily nonsensical enough to be a definite product of the Instant Songwriting technique, or an early Tyrannosaurus Rex composition.

The original group broke up in 1983 but have reformed numerous times around mainstay Alig Fodder. His singing on "Whatever Happened to David Ze" is suitably sombre, yet light (as nothing gets rammed down anyone’s throat on a Family Fodder recording) for a lovely reflection of the murdered Angolan political activist and musician. I suppose it would be great if Family Fodder became feted as post-punk legends, and suitably rewarded, but they are much less likely to stand still long enough for that to happen as they are to write a song charmingly taking the piss out of the very notion.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Imagine music resides everywhere that sound can travel. It flows from the faucet into the sink each morning, creaks out of the loose boards on the way up and down the stairs, and, incredibly, buzzes in your sweetheart's mouth as he or she snores noisily at 3 AM on Monday morning. The difference between music and not-music then pivots on the attention and consideration different sounds receive. Record them to tape, amplify and manipulate them, or set them into new patterns and a surprising, sometimes beautiful music can emerge. That's the music of The Breadwinner, the first album in Graham Lambkin and Jason Lescalleet's recently completed trilogy on Erstwhile.

Imagine music resides everywhere that sound can travel. It flows from the faucet into the sink each morning, creaks out of the loose boards on the way up and down the stairs, and, incredibly, buzzes in your sweetheart's mouth as he or she snores noisily at 3 AM on Monday morning. The difference between music and not-music then pivots on the attention and consideration different sounds receive. Record them to tape, amplify and manipulate them, or set them into new patterns and a surprising, sometimes beautiful music can emerge. That's the music of The Breadwinner, the first album in Graham Lambkin and Jason Lescalleet's recently completed trilogy on Erstwhile.

Recorded in 2006 and '07 at Graham Lambkin's home in Poughkeepsie, New York, The Breadwinner claims to be a collection of "musical settings for common environments and domestic situations." As it turns out, the music itself was derived almost entirely from noise captured around the house. Everything from water glasses to July 4th fireworks and squeaky hinges made the cut, so the music reflects the spaces and occasions for which it is apparently intended (tongue-in-cheek or not).

But the album isn't just the product of two guys wondering about the kitchen, living room, and bathroom with various microphones and some magnetic tape. Besides the keyboard and piano used on "Listen, the Snow is Falling" and "Lucy Song," the duo utilize their recordings as sound sources, deriving unearthly tones and igneous rhythms from the speeding up and slowing down of the source material. If the recording process doesn't make itself obvious in one way or another, the quality of the various sounds still point to it. On "E5150/Body Transport," a droning, out-of-body experience slowly resolves into a steady snore, suggesting that whole piece is actually an appropriated nightly annoyance. "Two States" compares and contrasts events that must have taken place at separate times. The mix is too solid, the balance too spot on for it to have happened without some tinkering.

Graham and Jason transform every room and make every object in those rooms new, whether by manipulation or by the arrangement of contrasting noises and complimentary sounds. Solid objects like the bedroom radiator or the fire place lose their rigid form and become malleable. That in turn gives the duo the freedom to re-contextualize everything, from mumbled voices to everyday appliances.

Mundane sources such as these typically keep emotional or communicative content well in the background. What we're supposed to do is listen to the sounds as sounds, not look for a message from the composers. After all, how could a refrigerator possibly speak to a sane person?

Perhaps unexpectedly, Lambkin and Lescalleet have left something personal in the mix, so maybe the fridge does just that: speak. First, there's the titles, which Graham and Jason probably understand better than the audience. But there's a Black Sabbath reference in there, and maybe one from The Hobbit too, and the aforementioned "Lucy Song" sticks to the ears with its bittersweet melody. The music moves through several moods, some ominous, others calming, and the reason for either isn't always clear. But the point is that the moods are there. So where are they coming from? "Listen, the Snow is Falling" can't help but communicate with its stunning sense of stillness and beauty, some of which is generated by the simple presence of a flickering fire. Even if the song were called "Track One," it would convey memories, feelings, and ideas.

And memory seems to be part of what Graham and Jason are up to with these songs. They make the lowly spoon and water glass speak to sensations usually provoked by rock 'n' roll songs, familiar melodies, conventional rhythms, and good books. The whole microcosm of Lambkin's house is laid bare for those curious enough to check it out. But, what about the experience of finding those noises, or the people who were around when they were made? There are obviously human noises on the record, but the figures themselves are conspicuously missing, or at least hidden. Which brings up a good question: is the breadwinner of the title the two musicians who made the record, or is it the house itself? Could it be the world at large, or is it maybe an unnameable something else?That blank spot there between the lines, where the music echoes out from invisibly?

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The Opalio brothers are certainly no strangers to uncompromising, indulgent mindfuckery, but their latest effort is extreme even by their own standards.  Stretched out across six discs, Roberto and Maurizio use their weird arsenal of homemade instruments and detourned toys to create an absolute monolith of abstract psychedelia.  Simultaneously nightmarish, overwhelming, and inspired, My Cat is an Alien have concocted an epic, brain-frying bad trip like no else before.

The Opalio brothers are certainly no strangers to uncompromising, indulgent mindfuckery, but their latest effort is extreme even by their own standards.  Stretched out across six discs, Roberto and Maurizio use their weird arsenal of homemade instruments and detourned toys to create an absolute monolith of abstract psychedelia.  Simultaneously nightmarish, overwhelming, and inspired, My Cat is an Alien have concocted an epic, brain-frying bad trip like no else before.

In the realm of crazily ambitious and dauntingly long albums, Psycho-System is very much akin to something like LaMonte Young's The Well-Tuned Piano rather than a run-of-the-mill pile-up of new material: this is simultaneously a very narrow and a very deep album.  Like Young, the Opalios essentially plunge so unapologetically deeply into their theme of choice that it gradually becomes something of a transcendent experience.  Perhaps "one theme exhaustively explored" is a bit of a reductionist view in this case, but I think it probably provides the clearest possible view of what the duo set out to do.  While the nebulous theme in question certainly evolves a lot of the course of the set's nearly 4-hour running time, Psycho-System feels much more like a single enormous, slowly evolving epic than six discrete shorter pieces.

Structurally, most of Psycho-System can be reasonably classified as drone, but with the caveat that it generally sounds quite...well...alien.  There is definitely a strong "outsider art" bent to the precedings, as many of the sounds that the brothers generate feel uncomfortably artificial, queasy, and dissonant, like someone is horribly abusing a battery of modular synthesizers.  In actually, however, it is hard to say quite what the Opalios are using to generate their otherworldly racket at any given time, as their extensive list of instrumentation includes such eccentricities as modified electronic devices, "alientronics," and a space modulator.

Notably, however, that list also includes items like a self-made double-bodied string instrument, a handmade pocket harp, and an antique zither.  Again, I have no idea which of those Maurizio is using at any given time, but there is recurrent, prominent use of a rattling stringed instrument that sounds like a koto throughout the album and that is what makes the whole thing work.  Those clear, sharp, and melodic passages are the perfect foil to the rest of the album's swirling, bubbling, buzzing, and humming otherness.  Psycho-System always sounds unique, but it is at its best when its spacier, lysergic tendencies come together with its more timeless, human ones.

Not every song adheres to that vague template though.  The most notable divergence is "Delirium," which combines Roberto's eerie wordless vocals with distantly clattering percussion and a hissing rumble to achieve an impressive degree of Kubrickian cosmic horror.  Another interesting aberration is "Bipolarism," which marries strangled-sounding guitar-like noise with insistently chirping electronics, though it later reaches an impressively crunching and cathartic percussion crescendo.  While the two pieces sound nothing alike, they do share a common trait in that they are much more minimal and space-filled than the rest of the album.  I have no idea of that was a deliberate sequencing choice or not, but the presence of two extended oases of differing density and texture makes the rest of the album's claustrophobic, hallucinatory maelstrom much more effective and listenable.

Notably, Psycho-System's six pieces were all recorded in real-time single takes over a three-day span, which surprised me: there is a lot going on here and it all feels very deliberate.  That goes a long way towards explaining the length though, as it takes a long time for just two loop-happy musicians to assemble the kind of snowballing unearthly racket that the Opalios have unleashed upon the world.  Whether or not this set would have been better if it were greatly shortened by overdubbing and aggressive editing is difficult to say.  It probably would be much more listenable and accessible, but I did not have much trouble making it through all six discs and I think the experience probably benefits a lot from being so exhausting and overwhelming.

Verdicts like "good" or "bad" seem irrelevant for an effort like this, which I think the Opalios understood perfectly when they were making it: Psycho-System comes with a warning sticker indicating that the album could potentially cause a psychotic break with reality with high volume and prolonged exposure.  That is a remarkably apt description of my own experience, I think–MCIAA definitely delivered what they set out to do.  Obviously, something this massive, difficult, and indulgent is probably unlikely to win the duo many new fans, but any curious aspiring psychonauts out there may rest assured that this is about as "outer limits" as music gets.  Also, I am pleased to report that my own psychotic break with reality does not seem to have been permanent.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

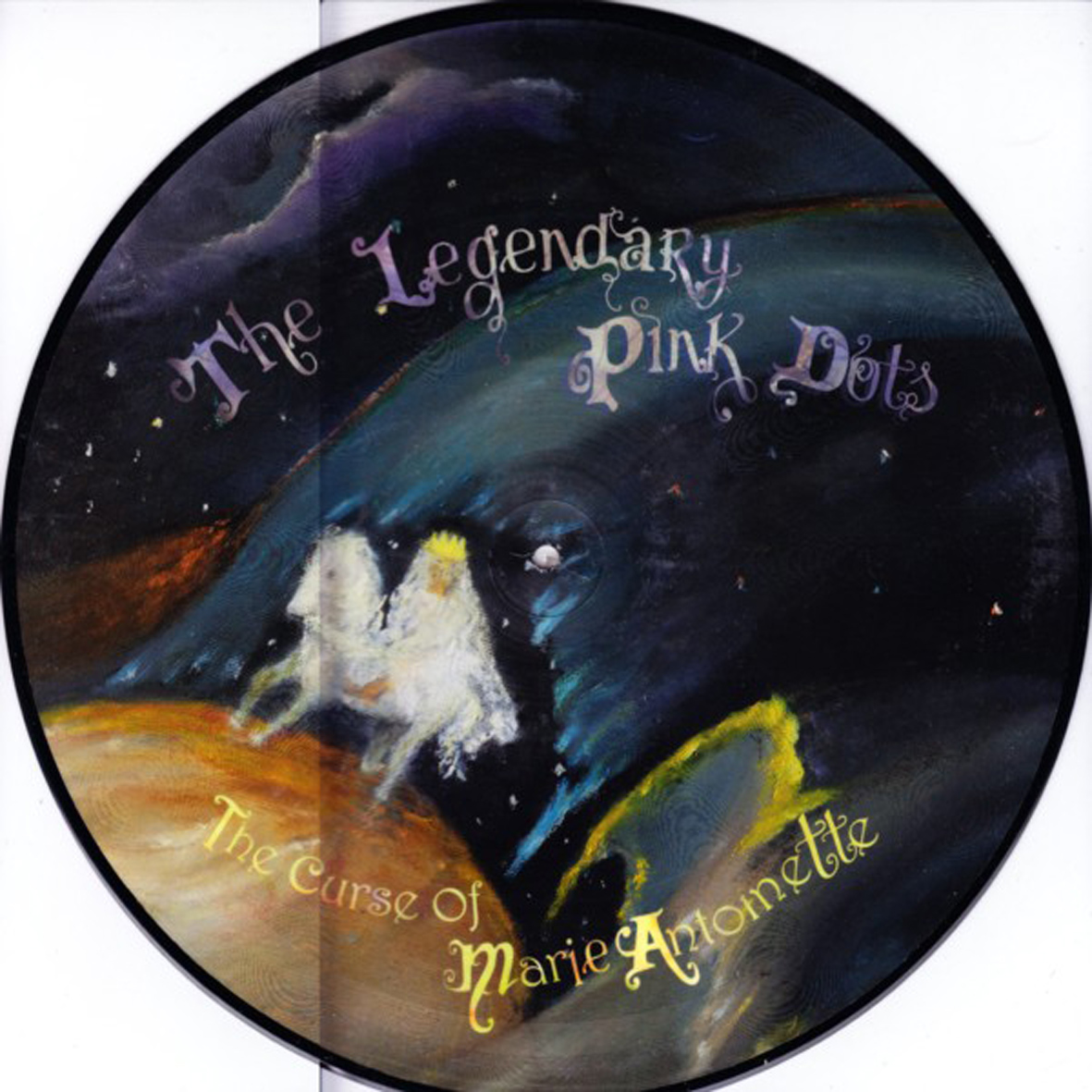

In typically perverse fashion, LPD bring their wildly prolific year to a close by burying their absolute best material on the second side of an extremely limited Italian picture disc (though it has thankfully now been made available digitally). The first half is not bad either, but the creepily phantasmagoric closer "Ghost of a Summer to Come" is one of the strongest arguments for Edward Ka-Spel's genius in recent memory.

In typically perverse fashion, LPD bring their wildly prolific year to a close by burying their absolute best material on the second side of an extremely limited Italian picture disc (though it has thankfully now been made available digitally). The first half is not bad either, but the creepily phantasmagoric closer "Ghost of a Summer to Come" is one of the strongest arguments for Edward Ka-Spel's genius in recent memory.

The Curse of Marie Antoinette is a concept album in which "a reincarnated witch claims one unwary soul and traps him in another dimension," which basically means that it is more or less business as usual for Ka-Spel and company.  Legendary Pink Dots' albums are always full of strange characters and cryptic themes, so the only real difference between this album and a "normal" album is that the songs form a narrative arc of sorts.  That ambitious long-form structure takes a while to become clear though, as the album's first half is fairly straightforward by Dots standards.

It is also a bit unpromising and uneven, though not exactly disappointing, as all three pieces boast at least one idea that I like (even if that does not necessarily translate into great songs).  The opening title track, for example, is a somewhat strident and exposition-heavy bit of piano-based chamber pop that unexpectedly dissolves into dreamlike haze around the halfway part.  "Something's Burning" is another song-like piece, but it is much more understated in tone than its predecessor and a bit too slow-moving for my taste.  Most of the individual elements are likable, but there is not much to it: just a plinking percussion loop, some cacophonous noises, a quasi-operatic female vocalist, and Ka-Spel's occasionally compelling vocals.  The side then ends with the nearly 9-minute instrumental "Hallucination 33" and it is Time To Jam.  Though "Hallucination" admittedly boasts a very cool and propulsive bass line, it also features a hell of a lot of wah-wah guitar noodling, which unfortunately makes it a song that I will not be listening to again.  However, it ends in a flurry of (presumably) dimension-shredding abstract noise that is the harbinger of much better music to come.

The droning, minimal "Catwalk" opens the second half in impressively deranged and uneasy fashion, as Ka-Spel delivers a beautifully haunting monologue over a bed of space-y noises, minimal synth throb, and an insistent clacking rhythm ("keep your arms stretched wide, friend, because that big, wide world below wants to consume you...whole").  It unexpectedly ends with a rather pretty and shimmering synthesizer coda though, which segues into quite a lovely ambient soundscape ("Ballerina on a Race Paper Leaf").  The album then concludes with the tour de force of the aforementioned "Ghost of a Summer to Come," which is easily among the best of Ka-Spel's monologue/soundscape pieces.  For one, the underlying music is wonderful, sounding distant and deeply warped and providing just enough coloration make even Edward's early description of the protagonist's picnic preparations sounds disturbing.  From there, it only gets better and better, unfolding into a flawlessly executed, blackly funny. and utterly mesmerizing tale of dawning horror.

I think I have been sufficiently conditioned at this point to never expect an entirely flawless album from Legendary Pink Dots, as regular over-indulgences and misfires are inevitable when a band is in a constant state of evolution and experimentation.  The Dots come admirably close this time around though, as The Curse of Marie Antoinette is at least half of a perfect album, sustaining unwavering greatness for over 20 minutes once it truly gets rolling.  Also, I suspect that many LPD fans will enjoy the album's first half much more than I do (particularly those who do not share my extreme antipathy towards guitar solos).  In any case, Marie Antoinette delivers three wonderful new songs, one of which ("Summer") is not just essential by LPD standards, but is one of the finest pieces recorded by anyone this year.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

Legend has it that more than a thousand years ago King Gasil of Gaya ordered a stringed instrument to be created. Archaeology suggests that same instrument, the gayageum, may have been made even earlier. Either way, de Jaer's compositions have a quality that is both ancient and modern.

Legend has it that more than a thousand years ago King Gasil of Gaya ordered a stringed instrument to be created. Archaeology suggests that same instrument, the gayageum, may have been made even earlier. Either way, de Jaer's compositions have a quality that is both ancient and modern.

In something of a twist to expectation, this album is performed by Kim Hyunchae and Lee Hwayoung, two women young enough to have their high schools included on the sleeve notes. Their dexterous fingerwork and subtle approach to pacing and space allows them to reveal the calmness and combustion in violinist Baudouin de Jaer's compositions. Honoring a long tradition of Korean music, Gayageum Sanjo is aesthetically complex, bracing, and challenging, with a prelude and five sanjos linked to cosmological, mythological, and literary themes. The word sanjo means "scattered melodies" and the form is said to have been influenced by shamanistic music and the epic stories of the southwestern region, none of which is lost on de Jaer who spent six years composing this album.

A sense of tranquility is underlined by the 11 part section entitled "Cavitri," after Paul Verlaine's poetic tale of the woman who remained impassive for three days and nights, without moving "legs, bust, or eyelids," in order to save her husband. During this piece de Jaer also introduces percussive elements associated with Indian raga. As with "Cavitri," the titles "Earth Around The Sun," as well as "Elasticity" and "Chess Study" provide clues as to the abstraction, space, and symmetry of the music.

Gayageum may usually be strung with nylon, metal, or silk, and while I think silk strings are used in this recording, certainly Hyunchae and Hwayoung produce metallic and synthetic tones as well as an amazing range of deep, high, organic, hollowed, and thudding notes and sounds. The placid sections are not over pretty and the occasional clusters of explosive, fluttering, fingerplay are unpredictable without feeling self-indulgent. Gayageum Sanjo is a good place to retreat from the times when life can feel like a random sensory assault.

"May Oblivion, that dark and gloomy assassin, surround us,

or we be the target of Envy's bitter shafts,

Let us do as Çavitri, remain impassive,

But as she, at heart have a noble intention."

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

After a surprisingly quiet year, Keiji Haino not only reignites the engines that power Fushitsusha but also forms this new trio with Stephen O’Malley and Oren Ambarchi. While I have yet to hear the new Fushitsusha album, Nazoranai hit the same spot as Haino’s most infamous group. Yawning chasms of feedback, pitch black silences and rock distilled down into its most concentrated acts of musical rebellion, this is up there with any of Haino’s best.

After a surprisingly quiet year, Keiji Haino not only reignites the engines that power Fushitsusha but also forms this new trio with Stephen O’Malley and Oren Ambarchi. While I have yet to hear the new Fushitsusha album, Nazoranai hit the same spot as Haino’s most infamous group. Yawning chasms of feedback, pitch black silences and rock distilled down into its most concentrated acts of musical rebellion, this is up there with any of Haino’s best.

Beginning with a tense and sparse arrangement of Ambarchi’s rhythmic percussion, Haino (on guitar and vocals) and O’Malley (on bass) begin casting out a net of gossamer thin notes. The music is oily, pitch-black and slithers out of the speaker like a deep-sea monster. Haino’s voice runs from the urgent to the menacing within a breath as the momentum slowly builds up and up during "Feel the ultimate joy towards the resolve of pillar being shattered within you again and again and again." Pauses eclipse the music as the power grows gradually over the song’s 24-ish minutes (unfortunately split between two sides on the vinyl version). Before I know it, O’Malley and Ambarchi are ploughing through the earth with a solid, powerful rhythm as Haino sets his guitar ablaze with a screaming anti-solo that almost causes the record to give off sparks (it is times like this that I understand Haino’s compulsory sunglasses).

"Not a joy to come closer but so-called a sacred insanity has finally appeared" sees the group entering a loose, Crazy-Horse-on-downers mode; a languid bassline being torn to shreds by Haino’s torrent of serrated steel guitar playing. It honestly would not surprise me if Haino used barbed wire instead of normal guitar strings. While there is little Haino has done that I have not loved, his forays away from his Gibson SG never reach this same sort of magical intensity. It is moments like this where he reminds me that he is an absolute demon on those six strings. He strums a vaguely rhythmic motif, letting the reverberations ever so slightly feedback while O’Malley and Ambarchi circle like sharks around him.

O’Malley and Ambarchi slip free from their respective background roles to take more of the limelight during "Getting a bit blurry brush up your cartel and devote it to something;" Ambarchi pounds the drums like Jon Bonham in slow motion while O’Malley’s snarling bass scratches out a patch of ground, stalking Ambarchi like he was some kind of big game. Haino seems removed from the proceedings, creating a trilling screen of trebly tremolo guitar. The music fits perfectly with the stunning artwork of women bathing by Lars Teichmann that adorns the album’s sleeve: white feminine figures barely there on a black background.

In contrast, the final piece (with the ultra snappy title of "Not to leave everything to the light outside of you but to be aware of the prayer "what do i want to do?" that exists inside of you, and let that go out of you as a light, or things might get worse, no?") is poignant and as close as Haino has ever gotten to a torch song (he even has a hint of Marc Almond about his singing during the song’s middle section). As Haino’s voice slips in behind the music, he unleashes a breath-taking guitar solo that stays strangely close to being melodic for most of its course. It is a glorious finish to such an abrasive and beautiful album, both at odds and in keeping with what the trio have presented earlier in the album.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

AUN is definitely the work of Christian Fennesz, but it does have a distinctly different sensibility compared to the work he normally puts out under his surname. Rather than a suite of complex, evolving compositions, this feels more like a series of sketches, a rough draft for other works, that function just fine on their own (and obviously work well in a soundtrack context).

AUN is definitely the work of Christian Fennesz, but it does have a distinctly different sensibility compared to the work he normally puts out under his surname. Rather than a suite of complex, evolving compositions, this feels more like a series of sketches, a rough draft for other works, that function just fine on their own (and obviously work well in a soundtrack context).

A quick look at the track listing makes this rather quickly apparent:15 tracks, many of which clock in at under three minutes.While Fennesz is not as prone to sprawling, epic length compositions, his work usually consists of longer pieces than this.Some of the exceptions are the three tracks carried over from his recent collaborative album with Ryuichi Sakamoto, Cendre ("Aware," "Haru," and "Trace").

It also makes sense to have these shorter, barer pieces as part of a soundtrack rather than his usual rich, nuanced compositions.There is no doubt who is responsible for this material, from the gauzy, shimmering noise of opener "Kae" to "AUN40", the latter of which's ghostly melody and fragmented tones bear his unmistakable mark, although the closing half stretches into darker, bleak lands that are a bit out of character.

That sun-faded, nostalgic sensibility of Fennesz's best work also shows up on "Nemuru," which, especially due to its building complexity in the second half of the track, would not be out of place on a traditional LP from him.The same goes for "Nympha," which balances delicate synthetic textures and untreated guitar playing.Albeit sparse, the heavily processed, bitcrushed guitar and unidentifiable sounds on the brief "Mori" sound like a brief fragment of a longer purely album-oriented Fennesz work.

It is on pieces like "Sekai" and "Himitsu" where the disc feels less like finished work.The stuttering acoustic guitar on the former song and the digitized textures on the latter are quite compelling on their own, but make up the bulk of mostly threadbare, short tracks."AUN80" is the only time where this feels like a problem:the erratic guitar and dissonant bass noises feed into an ugly, messier sound that I have not heard from him too often, and thus I would like to hear more of this approach, but alas the piece is limited to only a few minutes.

I would not be comfortable calling this a new Fennesz album, given the structure of this disc, but it is not being marketed as such.It lacks the lush complexity of an Endless Summer or Black Sea, but for those works to be used in a soundtrack capacity, I think they would draw too much attention away from the film, which should never happen.Instead this album is one that compliments visuals, but also manages work well on its own.It still comes across as more of a series of demos and sketches, but it remains a quality work nonetheless.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The relationships between these four artists makes for a complex family tree on their own, and thus it makes perfect sense that there is a tangible sense of unity between these four sides of vinyl, something split releases often miss. Jeremy Lemos and Matthew Hale Clark play together in White/Light, while Ken Camden and Matt Jencik make up Kranky band Implodes. While each artist contributes very different sound material, they all complement each other quite well.

The relationships between these four artists makes for a complex family tree on their own, and thus it makes perfect sense that there is a tangible sense of unity between these four sides of vinyl, something split releases often miss. Jeremy Lemos and Matthew Hale Clark play together in White/Light, while Ken Camden and Matt Jencik make up Kranky band Implodes. While each artist contributes very different sound material, they all complement each other quite well.

It is Hale Clark's single, 12 minute piece that is perhaps the most different from the other three."SLC Suite" is a slow build composition starting with pristine silence and sparse acoustic guitar, the rate of playing grows faster and faster, and eventually is paired with some subtle countermelodies and cymbals.It is only in the final two minutes that everything seems to lock into a full band sounding folk arrangement, before coming to its end.

On the flip side, Camden provides two pieces that differ from one another, but are unified in the use of heavily processed guitar sounds that resemble modular synths more than stringed instruments."Moisture" is all about swirling abstract tones and dissonant buzzes, going into a distinctly sci-fi feeling contribution.The following "Algoma Summer" works with the same palette of sounds, but takes a more sweeping, soundtracky approach, even throwing in some almost proggy leads into a complex, varied track.

On volume five, Lemos' work as a sound engineer is on clear display.In comparison to the pieces on the previous volume, "Out with the Old" feels much more like modernist electronic drone.Tense, shrill passages make up the darker, bleaker first half, before slowly being shredded into static swells and digital glitch outbursts, calming back down in the final moments of the 10-minute composition.

Jencik leads off his half with the subtlety titled "Conservative Fucks," a brief piece of cold, dissonant noise and reverberated static.Melodic it is not, but its full coverage of the sonic spectrum, from rumbling lows to shrill highs, make it a powerful track.The longer "Hollow Bodies" sounds like a recording or a sample of a cello played loudly through a filter, mutating the sound just enough to sound unnatural, but not overtly so.Slight increases in volume lead to a clipping type effect that, through restraint, are a compliment more than a detriment to the quieter sounds.The muted sense of sadness leads it all to have a maximialist, blasting feeling of depressive ambient music.

While superficially these four pieces and four artists sound quite different from one another, there is a tangible synergy and mood that unifies them, leading to an unexpected consistency that is usually unheard of for two split 10" releases.Folk, prog synth sounds, and digital drone normally would not work together, but here it somehow does.

samples:

- Matthew Hale Clark - "SLC Suite"

- Ken Camden - "Algoma Summer"

- Jeremy Lemos - "Out with the Old"

- Matt Jencik - "Hollow Bodies"

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I could never quite understood why this Portland duo were not more popular, as their dreamy Twin Peaks/early 4AD/shoegazer aesthetic always seemed pretty likable to me (if a bit over-sedate).  Curiously, however, they have dramatically changed their sound for this album, their most high-profile release to date.  I cannot quite say that their shift into quasi-choral ambient doom is entirely an improvement, given that the new lack of actual "songs" is necessarily less engaging, but the better moments are pretty damn close to being audio heroin.

I could never quite understood why this Portland duo were not more popular, as their dreamy Twin Peaks/early 4AD/shoegazer aesthetic always seemed pretty likable to me (if a bit over-sedate).  Curiously, however, they have dramatically changed their sound for this album, their most high-profile release to date.  I cannot quite say that their shift into quasi-choral ambient doom is entirely an improvement, given that the new lack of actual "songs" is necessarily less engaging, but the better moments are pretty damn close to being audio heroin.

This brief four-song album begins in wonderfully sublime fashion with "111," which is built almost entirely upon Barbara Kinzle's wordless, almost sacred-sounding vocals.  It is roughly akin to a monophonic hymn in the vein of Hildegard von Bingen, but Kinzle's vocal tracks harmonize uncomfortably with one another, creating an instant ominous undercurrent.  Gradually, that unease intensifies as Birch Cooper's sizzling guitar squall sneaks in to form a roiling bed that ultimately consumes the whole song in a grinding, hissing crescendo.

"River" segues out of the chaos to reset the template: Kinzle and Cooper now sing a duophonic quasi-hymn.  It does not quite reach the heights of its predecessor though, settling into a languorous rhythm of guitar noise washes and brooding synthesizers rather than catching fire.  While I always enjoy my ambient with a healthy dose of grit and sizzle, The Slaves err a bit too much on the side of noise here, losing a bit of momentum by burying the piece's more human, distinctive elements.

"The Field" cedes center stage to Kinzle's glacial minor key synthesizer swells, which I suppose kicks off the "doom" portion of the proceedings in earnest.  Unfortunately, I suspect The Slaves think the song's brooding chord progression is a lot more compelling than it actually is, as it basically unfolds for five minutes with almost no variation.  It is a bit too gloomy for my taste, but its slow pulse is weirdly hypnotic if I am in the right mood.  Also, Cooper's billowing noise blooms give it a satisfying texture and unpredictability.

The album closes with its lengthiest piece, the nearly 13-minute "Born Into Light,"which makes a welcome return to the  album's earlier choral aesthetic.  Despite its funereal pace and atmosphere, it is one of the album's strongest pieces due to its slow-burning accumulation of density.  Also, Birch's washes of distortion are a bit more erratic and meaningful than usual–sometimes they transcend mere texture and actually threaten to tear through the heavenly, melancholy fog.  I think The Slaves definitely work best when they allow their songs a long time to stretch out and unfold.  Doom cannot be rushed.

Given that it marks a significant change in sound, Spirits of the Sun is surprisingly successful.  It admittedly hits a bit of a lull in the middle, but that lull is bookended by two excellent pieces.  I especially loved the haunting "111," as it managed to nail an unusual balance between faux-sacred, vulnerably human, and barely restrained chaos. Otherwise, I think The Slaves could probably benefit by allowing some of their previous song-like tendencies to return, as it would give their music a bit more character: I definitely prefer Grey Angel and Ocean on Ocean as far as complete releases are concerned.  As far as songs are concerned, however, "111" might be the best and most promising thing that Cooper and Kinzle have ever done.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

2009's polarizing God is Good alienated quite a few long-time Om fans, a situation that this album is highly unlikely to remedy–it looks like Al Cisneros' fascination with sitars, strings, and tablas is here to stay.  In fact, Om has never sounded less like Om, which I find a bit troubling.  Still, Al's ambition and intensity are almost sufficient enough to make it all work.  Despite its occasionally awkward attempts at grandeur and exoticism, Advaitic Songs is ultimately a very listenable and uncharacteristically varied batch of songs.

2009's polarizing God is Good alienated quite a few long-time Om fans, a situation that this album is highly unlikely to remedy–it looks like Al Cisneros' fascination with sitars, strings, and tablas is here to stay.  In fact, Om has never sounded less like Om, which I find a bit troubling.  Still, Al's ambition and intensity are almost sufficient enough to make it all work.  Despite its occasionally awkward attempts at grandeur and exoticism, Advaitic Songs is ultimately a very listenable and uncharacteristically varied batch of songs.

Before I begin chronicling my myriad frustrations with this album, I think it is important to point out that I actually love Om.  I think Al Cisneros is one of the most singular and compelling people making music right now and I will probably keep buying his albums forever.  Consequently, my exasperation with Om's recent work is that of a fan trying to come to grips with some seriously puzzling artistic decisions in the midst of otherwise stellar work rather than any kind of dislike.  I want (and expect) to love each new Om album, but lately there have been some serious flaws to struggle with.

The fundamental problem with Om is that Cisneros is brilliant in a very narrow way: Om are at their best when Cisneros is simply speak-singing his impenetrable but unsettling metaphysical dispatches over a propulsive ride cymbal groove.  The essence of Om is essentially "great drums" plus "unnaturally intense frontman who sounds like prophet that just emerged from a decade in the desert."  That is all.  Any divergence from that formula is a dangerous move and Cisneros diverges a lot here.

I can certainly understand his motivation though: it is clear that Al wants to avoid repeating himself and that is very hard to do with a palette of just bass and drums.  Also, some of his new ideas are quite good, particularly the crackling mullah call to prayer that opens "Sinai."  I have also belatedly come around to embrace Om's recent use of droning synths and sitars.  Unfortunately, there are some other innovations that work less well.  For example, Kate Ramsey's guest vocals in "Addis" are certainly likable, but they cause the band to sound a lot more like Dead Can Dance than Om (a problem that is compounded by the fact that Cisneros never sings and drummer Emil Amos sticks solely to the tambourine).

Also, while I like the texture and depth provided by Advaitic Songs' rampant cellos, violins, and violas, they are employed in a way that sits a bit uncomfortably within the Om aesthetic.  The band's greatest strength has always been its eschewing of hooks and melodies in favor of achieving a heavy, trance-like groove.  Adding lengthy, melodic string passages is not necessarily the kiss of death, but they tend to go for epic majesty here, which feels overdramatic amidst such understated music.  Besides, Cisneros' ominous shamanic vocals are gripping enough on their own.  The other problem is simply that Advaitic Songs is loaded with such instrumental motifs.  Sometimes they work well, sometimes they do not, but in both cases they are diluting the essential Om-ishness of the band.  In fact, I think Amos and Cisneros only lock into their characteristic killer groove in three of the five songs (and Al only nods to his metal past by stomping his distortion pedal for two minutes of "State of Non-Return").

On a more positive note, Om are as great as ever on the rare occasions when Emil Amos gets a chance play his full kit.  I could listen to him forever and I love that these songs have enough space to make every single nuance perfectly audible.  Cisneros is in similarly peak form, unleashing wonderfully sinuous bass lines and confounding me with his usual awesomely cryptic narratives ("light trickles through the adjunct worlds, the soul galleon prevails").  There are not any sustained bits of greatness on the level of God is Good's 19-minute "Thebes," but there are a number of shorter flashes of inspiration and Advaitic Songs is ultimately a much more coherent and fully realized work than its predecessor (though it might err on the side of overwrought at times).

Despite Om's over-reaching ambition and their puzzling reluctance to get visceral, lock into extended grooves, or play to their strengths, this is actually still a pretty enjoyable effort (even if it does not always sound quite like Om because too much light trickled into the adjunct worlds of strings and tablas).  I, of course, hope that this is merely another transitional effort rather than an endpoint, but the continued evolution of Cisneros' songcraft is very promising.  And I would still much rather listen to an uneven Om album than most other bands' best work.

Samples:

Read More