- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

There was a period between 2010 and 2013 in which Rachel Evans seemed like a universally celebrated and ubiquitous figure in the "experimental music" milieu, as she released a flurry of tapes and LPs on a variety of great labels in a very short span. Since then, she has embraced a considerably more quiet and homespun approach to her art, self-releasing a steady and increasingly eclectic stream of limited edition tapes/CDrs/art objects to the delight of fans like myself. This latest release is an especially divergent and ambitious one, as Evans rarely releases vinyl and even more rarely shifts her focus towards acoustic instrumentation or conventional songcraft. The latter deserves an asterisk though, as there is only one brief song lurking within these two longform soundscapes and it largely appears in submerged form, but it is still quite a good one regardless. While the appearance of that surprise song is very much an album highlight, it is just one part of a larger and wonderfully hallucinatory whole. In fact, If We Were Landscapes is strong evidence that the golden age of Motion Sickness of Time Travel is still unfolding and that Evans' acclaimed run of albums like Seeping Through the Veil of Unconscious was actually just the tip of an expanding iceberg of future delights.

There was a period between 2010 and 2013 in which Rachel Evans seemed like a universally celebrated and ubiquitous figure in the "experimental music" milieu, as she released a flurry of tapes and LPs on a variety of great labels in a very short span. Since then, she has embraced a considerably more quiet and homespun approach to her art, self-releasing a steady and increasingly eclectic stream of limited edition tapes/CDrs/art objects to the delight of fans like myself. This latest release is an especially divergent and ambitious one, as Evans rarely releases vinyl and even more rarely shifts her focus towards acoustic instrumentation or conventional songcraft. The latter deserves an asterisk though, as there is only one brief song lurking within these two longform soundscapes and it largely appears in submerged form, but it is still quite a good one regardless. While the appearance of that surprise song is very much an album highlight, it is just one part of a larger and wonderfully hallucinatory whole. In fact, If We Were Landscapes is strong evidence that the golden age of Motion Sickness of Time Travel is still unfolding and that Evans' acclaimed run of albums like Seeping Through the Veil of Unconscious was actually just the tip of an expanding iceberg of future delights.

I am not sure how the vinyl or CD versions of this release sound, but something noteworthy about the digital version is that it has an extremely quiet mix (so much so that I actually punched up the gain with software). I mention that primarily because this is an album that demands some real volume, as one of its most wonderful aspects is how Evans fluidly and stealthily blurs and transforms her moods and motifs. The opening "Self-Portrait in Decay" is a perfect introduction, as slowly heaving cello drones blossom into a layered fantasia of backwards vocals, elusive violin melodies, and deep moaning strings. Initially, it seems like a faint transmission of a ‘70s folk song is getting picked up by her amp, then it sounds like she is playing violin along with a lovely ballad on the radio, then it gradually emerges that Evans herself is the soulful balladeer. It is an absolutely gorgeous interlude and easily ranks among my favorite passages in Evans' discography. However, that swooning crescendo does not impede the evolving mindfuckery one bit. The second half of the piece dissolves that song fragment into a shimmering haze of uneasy harmonies, reversed melodies, and a menacing host of darker, sharper tones. The following "Your Layered Silhouette, Unwinding" is similarly brilliant, as another reversed melody winds its way into a curdled orchestral nightmare, then gradually melts into a coda akin to a ravaged tape of an organ hymn. Both pieces are fascinating and complex plunges into vividly realized and darkly psychotropic soundworlds, which makes If We Are Landscapes one hell of an album.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

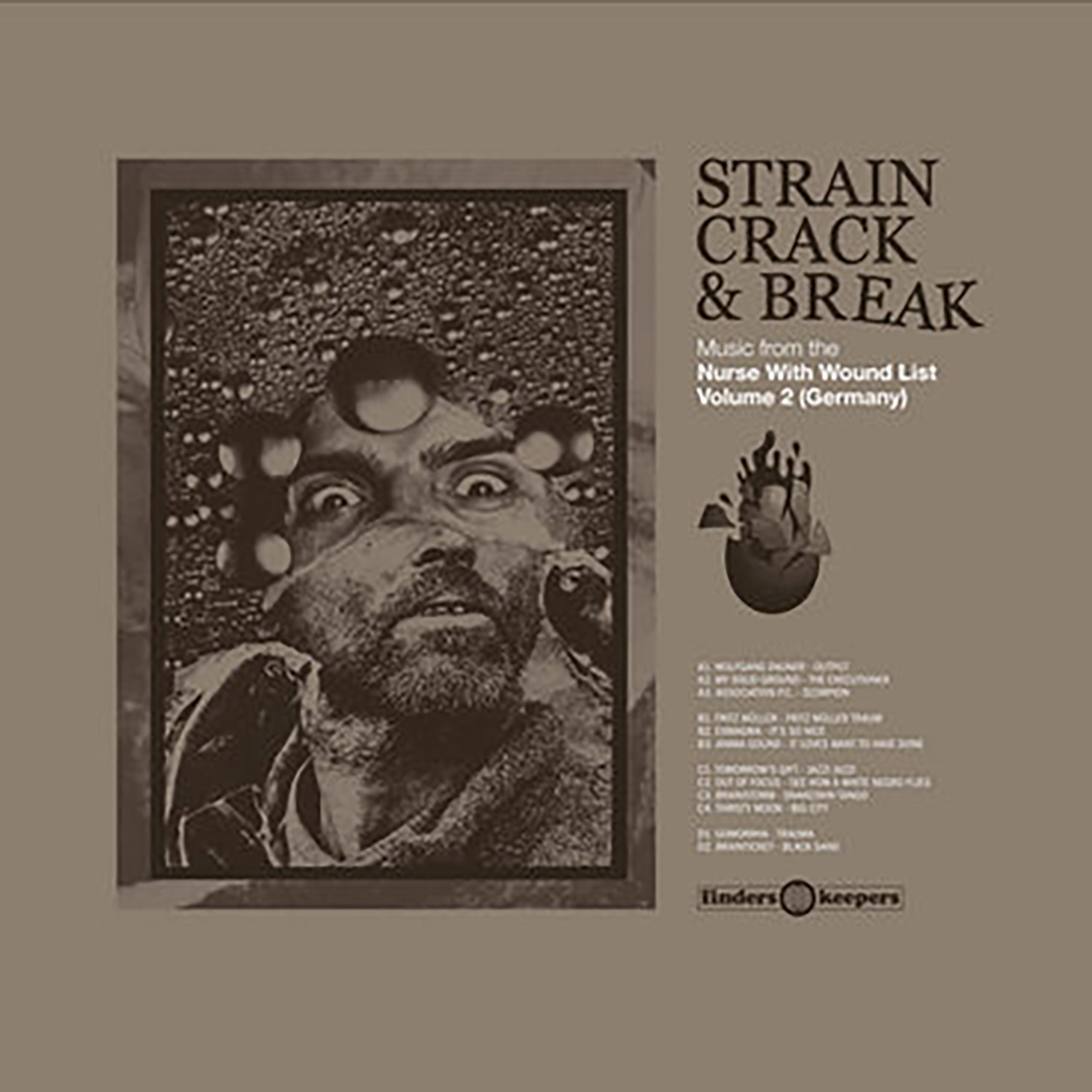

As a longtime Nurse With Wound fan, I have always been a bit amused and perplexed by the almost-religious reverence that people continue to have for Steven Stapleton's famous list. For one, it is hard to process that there was once a teenager in the '70s who was so cool that adults all over the world would spend the next forty years trying to replicate his record collection. Secondly, it seems like any underground bands from that era who have managed to remain obscure until now have probably earned that fate for valid reasons, as there have been plenty of blogs and reissue labels tirelessly unearthing and championing freaky sounds since the advent of the internet. Consequently, when this series was announced, I wondered what could still possibly be left undiscovered. That said, the idea of a Stapleton-curated tour of the most outré and adventurous prog, jazz, and avant-garde artists of the early- and mid-1970s still packs quite an appeal for me, so I am delighted that this better-late-than-never series exists. It admittedly took me a while to warm to the French volume, as I tend to run screaming from proggy indulgence and unfiltered Dada antics and there was plenty of both, but there were definitely some gems as well. Unsurprisingly, this stronger second volume features an even higher proportion of such gems, as it is not a mere coincidence that krautrock had a larger cultural impact than its French counterpart.

As a longtime Nurse With Wound fan, I have always been a bit amused and perplexed by the almost-religious reverence that people continue to have for Steven Stapleton's famous list. For one, it is hard to process that there was once a teenager in the '70s who was so cool that adults all over the world would spend the next forty years trying to replicate his record collection. Secondly, it seems like any underground bands from that era who have managed to remain obscure until now have probably earned that fate for valid reasons, as there have been plenty of blogs and reissue labels tirelessly unearthing and championing freaky sounds since the advent of the internet. Consequently, when this series was announced, I wondered what could still possibly be left undiscovered. That said, the idea of a Stapleton-curated tour of the most outré and adventurous prog, jazz, and avant-garde artists of the early- and mid-1970s still packs quite an appeal for me, so I am delighted that this better-late-than-never series exists. It admittedly took me a while to warm to the French volume, as I tend to run screaming from proggy indulgence and unfiltered Dada antics and there was plenty of both, but there were definitely some gems as well. Unsurprisingly, this stronger second volume features an even higher proportion of such gems, as it is not a mere coincidence that krautrock had a larger cultural impact than its French counterpart.

Much like the first volume, this latest one is packed full of unfamiliar names, which is an impressive feat given how deeply fans have mined '70s German music for killer obscurities. I was, however, vaguely familiar with Wolfgang Dauner and Limpe Fuchs beforehand, probably because they are responsible for some of the album’s most weird and cacophonous moments and that tends to be my wheelhouse. Dauner's piece, for example, sounds like several fusion bands falling down a flight of stairs, while Anima-Sounds' piece captures a (possibly nude) Fuchs wildly free-drumming and yelping along with a sliding and blurting chaos of homemade instruments. It is easy to see how the latter would have blown some goddamn minds at the time, though it does leave something to be desired in the realm of songcraft. The bulk of the album's other luminaries tend to exist in a gray area where jazz, prog, and psychedelia all blur together into unfamiliar new strains. For example, Association P.C.'s "Scorpion" resembles a Miles Davis-less Bitches Brew session, while the feral-sounding Exmagma call to mind Richard Hell or James Chance fronting King Crimson. Elsewhere, My Solid Ground evokes a baffling collision of This Heat and early Coil with the organ bombast of Emerson, Lake, and Palmer. I dearly wish the latter element was absent, but the non-organ passages are right up my alley. That said, the most wonderful surprises are the two lengthy jams that close the album. In Thirsty Moon's "Big City," a very NWW-sounding percussion motif steadily builds into a heavy rolling groove flavored with subtle elements of sound collage that rivals much of Can's stronger work. Gomorrha's "Trauma" is similarly driven by a muscular beat, but instead blossoms into a molten tour de force of spacey psychedelia. Yet another favorite is the hallucinatory marching band mindfuck of erstwhile Neu!/Kraftwerk member Eberhard Kranemann's "Fritz Müller" guise. The rest of the songs make a compelling and varied suite of inspired oddities, but the Gomorrha, Thirsty Moon, and Fritz Müller pieces all felt revelatory enough to trigger an immediate album-hunting binge. While Steven Stapleton has been one of my favorite artists for ages, it is now dawning on me that he is one hell of a great curator as well.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

It is quite a daunting task to keep up with Laurent Jeanneau's massive, continually expanding, and oft-challenging discography, but his vinyl releases always tend to be strong and focused statements worth investigating. In that regard, Jeanneau is having quite a great year, as this latest LP is his third excellent album of 2021 (Kink Gong's Zomia Vol. 1 and Sublime Frequencies' Mien (Yao) being the other two). Zomianscape continues Jeanneau's fascination with "Zomia," which is a half-conceptual/half-geographic term for the ethnic minorities in the hills and mountains of Southeast Asia who live outside national laws and customs. The term was first coined by historian Willem van Schendel in 2002, but it was James C. Scott's The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia that particularly struck Jeanneau, as he conceived of the Zomia series as a "mythological soundscape inspired by a semi-utopic region where state rules don't apply." The raw material for these first two longform "Zomianscapes" was recorded over ten years in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and China, but the boundaries between individual cultures, field recordings, and Jeanneau's own contributions are beautifully dissolved into a mesmerizing stew of hallucinatory sound collage. I suppose Zomia Vol. I achieved a similar end in more bite-sized doses, but this follow up offers a deeper, more immersive plunge.

It is quite a daunting task to keep up with Laurent Jeanneau's massive, continually expanding, and oft-challenging discography, but his vinyl releases always tend to be strong and focused statements worth investigating. In that regard, Jeanneau is having quite a great year, as this latest LP is his third excellent album of 2021 (Kink Gong's Zomia Vol. 1 and Sublime Frequencies' Mien (Yao) being the other two). Zomianscape continues Jeanneau's fascination with "Zomia," which is a half-conceptual/half-geographic term for the ethnic minorities in the hills and mountains of Southeast Asia who live outside national laws and customs. The term was first coined by historian Willem van Schendel in 2002, but it was James C. Scott's The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia that particularly struck Jeanneau, as he conceived of the Zomia series as a "mythological soundscape inspired by a semi-utopic region where state rules don't apply." The raw material for these first two longform "Zomianscapes" was recorded over ten years in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and China, but the boundaries between individual cultures, field recordings, and Jeanneau's own contributions are beautifully dissolved into a mesmerizing stew of hallucinatory sound collage. I suppose Zomia Vol. I achieved a similar end in more bite-sized doses, but this follow up offers a deeper, more immersive plunge.

Even with the aid of Jeanneau's thorough notes about the content of each piece, it is a hopelessly impossible task to try to describe what happens in either of these two Zomianscapes in any kind of detail. For the most part, however, both pieces are a shape-shifting swirl of traditional lutes, hand percussion, panpipe-like mouth organs, and a wide array of singing and speaking voices from a cast of talented contributors such as "Bulang Lawa Man and Drunk Wife." In the album description, Jeanneau mentions that he simultaneously (and fatefully) discovered the Ocora and GRM labels as a teen, which concisely conveys significant insight into the unique collision of impulses shaping the Kink Gong aesthetic. In practical terms, Jeanneau's ocora-inspired devotion to recording and preserving rarely heard traditional music means that the absolute baseline for any Kink Gong album is "there will probably be voices, instruments, and melodies unlike anything I have ever heard before." Naturally, each Kink Gong album is shaped significantly by the character of the recordings Jeanneau uses as well as the degree of GRM-style electronic experimentation. The latter is abundant on Zomianscapes, as each piece is vibrant, hallucinatory, layered, and endlessly in flux (and both pieces are great). The warbly mouth organ in the opening piece calls to mind a traditional Laotian variation of Fennesz's Endless Summer in its early moments, but soon embarks upon a trip through a lysergic fog of fragmented voices and twanging strings en route to a hypnotic finale of looping vocal melody. The second piece is even better still, as it slowly blossoms from metal percussion into a haunting chorus of chanting women over quavering drones. For his final trick, Jeanneau then dissolves it all into a smeared and hissing crescendo of ringing metal, clapping hands, and an escalating roar of garbled voices and murky dissonance. While I have only experienced a mere fraction of Kink Gong's 100+ albums at this point, this one is definitely a favorite among the ones I have heard.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

Western Massachusetts' loudest deadhead Josh Landes has followed up his live set Unrelenting Barrage of Flowers and Amethyst Energy from last year with a new studio album (well, at 18 minutes, it counts as an album in the noisecore world) that furthers his legacy of intensity and absurdity. Balancing electronic blowouts with creative field recordings, it is another disc of explosive fun.

Western Massachusetts' loudest deadhead Josh Landes has followed up his live set Unrelenting Barrage of Flowers and Amethyst Energy from last year with a new studio album (well, at 18 minutes, it counts as an album in the noisecore world) that furthers his legacy of intensity and absurdity. Balancing electronic blowouts with creative field recordings, it is another disc of explosive fun.

Admittedly, these 23 songs (that are only around 30 seconds each in length) sound like broken up segments of three longer pieces rather than individual pieces. They flow consistently into one another, with each track marker opening with a vocal outburst and what sounds like Landes restarting the max BPM drum machine. Beyond that, the sizzling electronics and sputtering noises continue uninterrupted from one short burst to the next. Burnt White Elephant makes for the most chaotic of his albums that I have heard thus far, with the erratic electronics blasting from beginning to end, but never in the form of loops or anything sequenced. It is more like Landes set his gear up and just rolls it down a hill, and I mean that as a compliment.

Around these short blasts, he includes a series of field recordings captured around the Berkshires region, something like "Wormholes and Megaliths" featuring what sounds like rain and passing by a jazz band, while "Van Deusenville Railroad Blues" is exactly what it sounds like: the sound of trains passing through. The album closes on “Harry Bids You Goodnight” which is just shy of one minute of a snoring cat. Intentional or not, Burnt White Elephant seems like a day in the life of a noise artist: harsh, distorted art outbursts punctuated with the quiet mundane nature of life.

Like every Limbs Bin release I have heard, Josh Landes again blends the intense with the absurd. His work is as aggressive or violent sounding as any great harsh noise/power electronics/whatever genre release should, but devoid of the macho posturing or juvenile provocation. Instead it is just the right amount of silliness that makes the chaos and hostility fun, without dulling its impact in the slightest.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

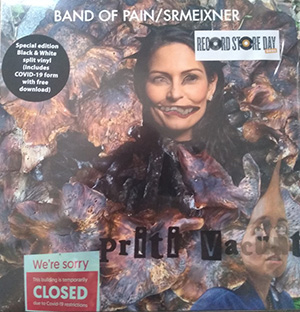

Taking a cue from the politicization of the COVID pandemic, Band of Pain (Steve Pittis) and Contrastate's Stephen Meixner teamed up for this collaborative single, with each taking the lead on a solo piece, and then a balanced collaboration to conclude. Heavily based on samples of speeches and news reports, it is certainly a politically charged work, but one that remains heavily rooted in both artists’ post-industrial and absurdist sensibilities.

Taking a cue from the politicization of the COVID pandemic, Band of Pain (Steve Pittis) and Contrastate's Stephen Meixner teamed up for this collaborative single, with each taking the lead on a solo piece, and then a balanced collaboration to conclude. Heavily based on samples of speeches and news reports, it is certainly a politically charged work, but one that remains heavily rooted in both artists’ post-industrial and absurdist sensibilities.

Band of Pain's "Priti Vacunt" is pretty overt in the target of their ire: UK Home Secretary Priti Patel. A self-described right wing hardliner, Patel was involved in a lobbying scandal around COVID-19 contracts, which is where most of this disgust comes from. The piece itself is a myriad of echoed speech samples and bent electronic tones. The droning, open spaces are unrelentingly bleak, with an insincere sounding sample of “sorry” punctuating the less identifiable moments. In the closing minutes Pittis brings in a thin, distorted rhythmic thump that is all too short.

On the other side of this 10", the Meixner helmed "Deceit" opens up with some pummeling drum programming, but soon the focus is shifted to some American evangelical preacher’s ranting about the disease and vaccination as a noisy, somewhat melodic passage is paraded through. What sounds like even further treated voice samples become an additional element, and Meixner utilizes an intentionally jerky stop/start dynamic throughout. The concluding collaboration "End Result" features less in the way of obvious voice samples but instead fragments of speech or other sounds, pulled apart and reconstructed into something entirely different. The layering is complex and the ambiguity is unsettling, bordering on creepy.

Contemporary political and social criticism aside, the two Steves have created a compelling single that certainly falls in line with their other works as Band of Pain and Contrastate. Idiosyncratic processing, heavily treated samples, noisy outbursts and even the occasional hint of rhythm feature heavily here.  Tempered with just the right amount of black humor (fitting the topic at hand perfectly), the final product reminded me of the unconventional and challenging sample heavy music that was coming out of the UK industrial scene during the mid 1990s (which makes sense given the inception of these projects), but still sounding completely contemporary, nicely hinting at nostalgia while staying modern and fresh.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

Recorded live at Tokyo’s Super Deluxe club in 2017, this trio's 10th release is dedicated to Hideo Ikeezumi, founder of the incredible P.S.F. label and Modern Music store who died the same day. Mr.Ikeezumi was a fierce and relentless advocate for Japan’s underground scene and an early champion of Haino. For this concert, the three agreed their unrehearsed improvisation would be “electronic” but not which instruments any of them would play. Haino also uses a double-reed horn, the suona, traditionally used in a variety of settings and rituals including funerals, producing blaring, high-pitched sounds for both the living and the dead. I find this a bold, delicate, fascinating, and ultimately rather moving, album; albeit with a title far too long to mention in such a brief review.

Recorded live at Tokyo’s Super Deluxe club in 2017, this trio's 10th release is dedicated to Hideo Ikeezumi, founder of the incredible P.S.F. label and Modern Music store who died the same day. Mr.Ikeezumi was a fierce and relentless advocate for Japan’s underground scene and an early champion of Haino. For this concert, the three agreed their unrehearsed improvisation would be “electronic” but not which instruments any of them would play. Haino also uses a double-reed horn, the suona, traditionally used in a variety of settings and rituals including funerals, producing blaring, high-pitched sounds for both the living and the dead. I find this a bold, delicate, fascinating, and ultimately rather moving, album; albeit with a title far too long to mention in such a brief review.

Other than the suona, it is not always possible to know who is making which sound, and that does not really matter. The important thing is to hear the trio responding to each other brilliantly, without flashiness, and feel the music retaining it's intensity even as the longer pieces take their time to develop. These improvisations have (known and unknown) creative methods by which elements of harmony, melody, and rhythm are achieved. The group's abstract expressionism, unpredictable, coherent, and deliberate, allows gives plenty of opportunity for subjective interpretation. At times I imagined an airtight module in space, at others un-manned train trucks engaged in dubious activities far beneath a mountain. I heard traces of bleeping static buzz and pictured a dystopian wilderness, stalactites thawing and dripping in a radioactive cave, locusts crawling inside air ducts, an astronaut's life support system going into crisis mode, a security patrol blasting horns five light years away, and the feeling of waking from a nap to find the launderette is flooding. As with several albums by the group, it is possible to see Haino as the central figure, perhaps like an actor in a film, with O’Rourke and Ambarchi setting up the lighting, or changing the scenery, but on the other hand things seem nicely balanced, with perfectly equal exchanges. For example, as the suona wails with longer and longer notes like a grief stricken bird crying out into eternity, alternated with passages where Haino must be catching his breath, O’Rourke and Ambarchi provide deeper and lower tones, some gong-like sustain, a section of higher-frequency twinkling and pulsing, slow bass notes and a fading signal.

The shorter final track (of four) is full of whooshing, crackling, echo: a beautiful coda as if the machines somehow continued to play after the trio had gone, suggestive perhaps of a residue of life, or the detection of brain wave activity after physical death. By the way, Dewey Redman used to play the suona (which he called a “musette”) as did Mick Karn, who listed it as a “dida.” I must add that the album cover is stunning - Lasse Marhaug’s photograph from Norway, of the Ellingsrudåsen station on the Oslo metro, line 2. The last stop on the line; the exit that goes into the forest.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Legendary German kosmiche band Can is not a "hits" band. Despite being known for classic studio work with individual tracks such as "Vitamin C," "Halleluwah," "Mother Sky," and "Future Days," Can, first and foremost, are an improvisational band. While this was a core driver of their studio output, it is particularly evident in their live performances, of which bootlegs of assorted quality exist, noted for never playing a song the same way twice. Singer Damo Suzuki had left the group by this time and Can had released their sixth official studio recording, Landed, an album some fans identify as the marker of Can's slide from greatness. A meticulously produced album, the rock sheen of that studio album could not tell the story of Can's true nature. This polished bootleg — for which we have a devoted fan with large pants to thank — separates the studio mystique from the musicians, showcasing their enduring and practiced talent, revealing the genius of the band's four original members that forever make Can an icon of music history.

Legendary German kosmiche band Can is not a "hits" band. Despite being known for classic studio work with individual tracks such as "Vitamin C," "Halleluwah," "Mother Sky," and "Future Days," Can, first and foremost, are an improvisational band. While this was a core driver of their studio output, it is particularly evident in their live performances, of which bootlegs of assorted quality exist, noted for never playing a song the same way twice. Singer Damo Suzuki had left the group by this time and Can had released their sixth official studio recording, Landed, an album some fans identify as the marker of Can's slide from greatness. A meticulously produced album, the rock sheen of that studio album could not tell the story of Can's true nature. This polished bootleg — for which we have a devoted fan with large pants to thank — separates the studio mystique from the musicians, showcasing their enduring and practiced talent, revealing the genius of the band's four original members that forever make Can an icon of music history.

This legendary performance features Irmin Schmidt on keys, Jaki Leibezeit on drums, Michel Karoli on guitar, and Holger Czukay on bass. Live in Stuttgart 1975 is the first in a series of polished bootlegs, remastered from tape by sole remaining member Schmidt and longtime producer Rene Tinner, and available officially for the first time on various media formats, notably in a beautiful orange 3-disc vinyl version. There's not much revealing about the tracks at first glance, numbered simply one to five in German, with the shortest track clocking in at 9:31 and ranging to 35:58. Nor is there anything particularly revealing about the cover art, a stack of amps in a live setting superimposed with butterflies, moths, and the odd mosquito. It's not until cracking open the artifact is the essence revealed.

With thankfully only minimal crowd noise revealing this is indeed a live recording, Schmidt's spacey keyboard sounds introduce "Eins." Merely two minutes are given for what feels like a warm-up, before Czukay, Karoli, and Leibezeit converge perfectly with Schmidt in perfect union. Leibezeit's motorik and precise, almost machine-like drumming rounds everyone together, serving as an initial foundation to Karoli's guitar, providing him the freedom to build cascading sustained play around Czukay's pronounced bass lines, while Schmidt uses his keyboards to build up a distinct atmosphere encouraging the direction of the music. This magic happens within the first 5 minutes, with another 15 minutes left to go. By this time, the members have each fully tuned into each other, carefully listening for musical cues; a change in bassline rhythm, the introduction of a fresh guitar tone, keyboard intensity growing or withdrawing, or a shift in the drum pattern. By 7 minutes, the song has taken on a sense of urgency and developed a life of its own. Karoli may drop in a bit of blues here, Leibezeit a dose of jazz there, and Czukay taking over such that his bass becomes the lead instrument in the song. The incredible thing about all this is that it all works, fluidly shifting and changing, no curve ever missed in a journey of twists and turns, a well-oiled machine with no one single driver.

Each member's talent is evident, but none over another. It's astounding to hear the machine-like precision of Liebezeit's drumming, even at its most complex, revealing his practiced ability to deliver jazz, funk, reggae, and rock rhythms flawlessly, changing up without notice in a single track. It's no wonder he's been an inspiration for countless drummers. Similarly exciting is Karoli's fluidity to evoke staccato chords, fuzzed-out sustain, jazzy chords, and metal-worthy guitar solos, knowing exactly where to hold back. Well before bassists like Les Claypool and Flea made their instrument lead drivers in their respective bands, Czukay paves the way, especially evident in large swathes of "Drei." Furthermore, Schmidt's keyboards are a constant, underlying driver of mood, at times so subtly unobtrusive for the less keen listener until suddenly, there they are, front and center. Still, a second listen shows they never went away; in fact, for tracks like "Drei" and "Fünf," it becomes apparent they were vital to drive the track's mood and style.

The genius of Can reveals itself on Live in Stuttgart 1975 without a single lyric. Instead, one need only listen to the distinct abilities of each member — each instrument separated clearly through the miracle of modern remastering — and the incredible live energy to get swept up in the unique details of the band's live performance. None of the five tracks are reminiscent of any of the band's studio work, though keen ears will hear snippets from other works. Raw in all its glorious immediacy, this artifact may surprise listeners more familiar with the band's studio releases but brings a new dimension to the creative majesty that was Can.

Sound samples can be heard here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Seeing this release announced as music for "squares" or gated communities, unlikely to appeal to your "woke friends" made me approach it as one might any potential minefield. Learning that Julian Warner, aka Fehler Kuti, is a cultural anthropologist, actor, writer, editor, speaker, art festival curator and producer didn’t lighten the mood much as I feared an onslaught of dry polemic. What a relief then to simply get hooked by these hypnotic tunes - several of which were lullabies for Warner’s newborn child. Professional People reveals as a transcultural concept album, lightly touched with softly spoken wit, 8-bit space jazz, cosmic Euro-pulse, pan, chant, Afro-neon groove, wordless harmony, and melancholic synth. Some of the song titles can act as political signposts, but lyrics are few, mostly oblique, and any message subliminal: hidden in plain sight amid references to bureaucracy, cars, office buildings, home, leisure, gardens, and security. There is no holy indigestible agitprop, no denial of anyone else’s struggle, and Warner leaves academic language and analyses of class, race, and history for the books. He’s razor sharp, but kind, and rather than cutting with words he sprinkles sardonic humor and personal history in with broader observations. The whole record invites everyone to swing along together in our various states of alienated inclusion. Phew. I won’t hear many more enjoyable albums this year.

Seeing this release announced as music for "squares" or gated communities, unlikely to appeal to your "woke friends" made me approach it as one might any potential minefield. Learning that Julian Warner, aka Fehler Kuti, is a cultural anthropologist, actor, writer, editor, speaker, art festival curator and producer didn’t lighten the mood much as I feared an onslaught of dry polemic. What a relief then to simply get hooked by these hypnotic tunes - several of which were lullabies for Warner’s newborn child. Professional People reveals as a transcultural concept album, lightly touched with softly spoken wit, 8-bit space jazz, cosmic Euro-pulse, pan, chant, Afro-neon groove, wordless harmony, and melancholic synth. Some of the song titles can act as political signposts, but lyrics are few, mostly oblique, and any message subliminal: hidden in plain sight amid references to bureaucracy, cars, office buildings, home, leisure, gardens, and security. There is no holy indigestible agitprop, no denial of anyone else’s struggle, and Warner leaves academic language and analyses of class, race, and history for the books. He’s razor sharp, but kind, and rather than cutting with words he sprinkles sardonic humor and personal history in with broader observations. The whole record invites everyone to swing along together in our various states of alienated inclusion. Phew. I won’t hear many more enjoyable albums this year.

With the aid of stalwarts from The Notwist, Fehler Kuti builds a laid back sound with drive but also plenty of breathing space. Markus Acher's brilliant drumming is key, and Micha Acher adds sousaphone and trumpet flourishes. Equally, Sascha Schwegeler's steel drum helps make "Transatlantic Ideology" a standout track. Here Kuti gently references a popcultural and socio-theoretical Afro-Americanophilia in Germany that must be addressed as it deflects from anti-racist movements and away from other racist exploitations (systematic exclusion of Romani people, capitalist exploitation of eastern European migrant laborers). Off record he points out that Black Germans do not make up a racialized labor underclass, so in this sense the leftist fetish of the African American plight is devoid of its revolutionary potential when directed at the Black German. I say "gently" but, as with several stunning lines laid into the fabric of this album "Is a black man humanoid?" made me jump. I uncomfortably recalled the satirical essay "Are The Jews Human?" which got that awkward old stick Wyndham Lewis into a spot of critical bother. Whereas Lewis was brilliant but easily depicted as a brute, Warner’s unflinching honesty about his own status as a professional "manager of color" is his calling card. He insists his class are using the paradigm of diversity as a tool to escape their fate, without changing the class relations as a whole. Who better, then, to warn us: "This song is a song to end all ties, to say goodbye to old, and say hello to new, lies." If that sounds heavy, it’s actually as catchy as The Bonzo Dog Band doing "Terry Keeps His Clips On."

The album title alludes to the professional managerial class identified by Barbara and John Ehrenreich in 1977. The Ehrenreich’s argued that this group opposes the dominant capitalist owners yet views itself with some elitism as distinct from the working class. The PMC, they argued, should do away with it's condescension and elitism, go beyond bread and butter issues and make peace with the working class about art, culture, divisions of labor, psychology, and sexuality. This I simply have got to see.

Warner as Fehler Kuti has taken this lesson on board and does not get bogged down with explanations. He does not act as if he is in a minefield at all, and navigates it with ease. He hints and drops mystery instead of pointing or preaching. The album takes the form of musical massage to peacefully entice our relaxed senses towards toe-tapping and humming along. Many of the pieces feel like accompaniment for dancers doing short scenes in a stage play. Indeed the album is partly an offshoot of Warner’s play The History of the Federal Republic of Germany as told by Fehler Kuti und Die Polizei.

The pounding "Deutsche Passe" probably considers how the "foreign" may have a German passport but not be saved from the consequences of lingering post-Moneterist policy - at least that’s my take - but the robo-beat and groove dominates, even when the hideous Thatcherite "there’s no such thing as society" chorus arrives. "Automobile Love" throbs and hums with the lonely power of homogenous traffic heading to shared environmental oblivion, perhaps. The strange wobbly-sounding "Dark Boys" is another highlight. It touches on the notion that a certain group serve a useful purpose in being forever cast as stereotypical aggressor, victim, noble hero, or scapegoat, yet it's atmosphere of hyper-mournful dirge is the key factor. Just as slow, and thought provoking, is "Doggerland" with the repeated lines "This garden we had built for our children"... "the garden’s gone." A garden image has often been used in art as a symbol of broken dreams or lost innocence, from the Garden of Eden to the walled estate of the filmic Finzi-Continis, wherein a group of Italian jews devote their time and energy playing tennis in the sun, oblivious to the rising threat of Fascism.

Professional People benefits from some lovely instrumental pieces, and passages, which encase the aforementioned soft vocals and serious-as-your-life concepts in a protective shell of synths and delightfully sparse instrumentation worthy of the first couple of Aksak Maboul recordings. "Bürgebäude In Und Um Frankfurt" (Office Buildings In and Around Frankfurt) for example, has a comfortingly familiar sense of bland bureaucracy. "In Every City, In Every Aldi, The Blood of My Brothers and Sisters Taints Your Spargel" bubbles and twitches harmlessly like a backing track for an old school magician doing tricks. Eventually, Katja Kobolt speaks a few lyrics in Bosnian. This is one of two songs with a guest vocalist, as Warner does most of the singing and backing vocals himself. The title track is my least favorite, but thereafter the album hits an oblique and bizarre flow worthy of the fabulously impenetrable (and commercially disastrous) 1980s legends Sudden Sway. By which I mean it constructs a world unto itself as the consistently good tunes, snaking shapeshifting rhythms and quietly subversive mockery really get going. The Residents come to mind, as does Sun Ra, and there’s a clear nod to Grandmaster Flash on "Freizeit 20."

On "Home," Warner sings "If I ever enter history, what will the West have in store for me?" Another cool line, and also a veiled reference to the heartbreaking plight of one black couple who fought with the British in WWII and settled in Germany. In the 1970s they lived in fear that their past military actions exposed them to the threat of kidnap and murder by the Red Brigade. The irony of anti-imperial leftists evoking terror in the hearts and minds of former imperial subjects is tragic. As is the added ironic layer of those former imperial subjects becoming die hard conservatives in the hope of surviving the tides of time with their newly gained privileges intact. Like a funky komische W.E.B. Du Bois, Fehler Kuti strongly suggests that Germany, at least, has reached a biographical, political and historical juncture where the trajectories of race and class, once convergent, now drift apart. Although, as with the sublime final track "Wohlfart," which twinkles like Neu! fronted by Cathal Coughlan at his most endearing, you just won’t realize it from the clever way Warner/Kuti has styled his message.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I initially slept on this album, as the prosaic title made it sound like a collection of old and orphaned songs rather than a minor sound collage masterpiece. The former would be just fine by me (in a non-urgent way), but the fact that this album is actually the latter completely blindsided me. As the label puts it, Collin pulled "shining diamonds from his discography" and put them "in a new context with more recently recorded segments." In more practical terms, this means that the album beautifully bleeds together ephemeral highlights from Collin's discography into a soulfully mesmerizing, endlessly evolving impressionist fantasia. In its most striking moments, Music From Cassettes, Etc. makes me feel like I am a Dickensian ghost experiencing all the warmest moments from Collin's life through a flickering projector.

I initially slept on this album, as the prosaic title made it sound like a collection of old and orphaned songs rather than a minor sound collage masterpiece. The former would be just fine by me (in a non-urgent way), but the fact that this album is actually the latter completely blindsided me. As the label puts it, Collin pulled "shining diamonds from his discography" and put them "in a new context with more recently recorded segments." In more practical terms, this means that the album beautifully bleeds together ephemeral highlights from Collin's discography into a soulfully mesmerizing, endlessly evolving impressionist fantasia. In its most striking moments, Music From Cassettes, Etc. makes me feel like I am a Dickensian ghost experiencing all the warmest moments from Collin's life through a flickering projector.

The first side rolls in as a fog of tape hiss and crackle that sounds like a ravaged dictaphone recording of a bus tour somewhere in some exotic tropical place. Soon, however, a simple twanging acoustic guitar piece starts to fade in. It is quite a warm and deeply emotive performance, so I was sad to see it go as it gradually became consumed by a slowly oscillating hum that later dissipates into enigmatic dictaphone hiss once more. That theme of slowly dissolving vignettes is the heart of the album, but the variety, beauty, and cumulative power of them is what makes this album transcendent and bittersweet. On the A side, the dream parade makes further noteworthy stops at deconstructed blues and something akin to a tribute band that accidentally double-booked themselves as both Pink Floyd and The Dead C, but valiantly blurred them together to give everyone the concert of their lives. The playing near the end is absolutely amazing, as Collin whips up a rapturous Orcutt-level firestorm of wild hammer-ons and swooping slides for the volcanic finale. The second side offers a similarly mesmerizing but completely different phantasmagoria of fragmented delights. Sometimes I find myself at a languorous campfire jam in which lupine howls harmonize with a sliding melody, while at other times I am catching the fiery performance of a noise rock band from a reverberant alley. Elsewhere, Collin's collage sounds like a ravaged tape loop of an organ mass backing a demonic squall of white-hot electric guitar catharsis. Throughout it all, Collin maintains a perfect balance of soulful melody, lo-fi ruin, and sharp-edged feral intensity, the latter of which definitely surprised me (he sounds absolutely possessed during some of his solos). The whole album is great from beginning to end, as Collin hits one perfect moment of tender melody or viscerally howling noise guitar incandescence after another with nary a lull between them. This is an instant classic.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest album from Skelton seems intended to be a major new statement, though not quite a formal follow-up to last year's These Charms May be Sung Over a Wound, as double LPs are a real rarity in the prolific composer's discography. If it was not intended as such, it certainly has the ambitious conceptual framework and focused power of his strongest work. For these four pieces, Skelton used a self-devised divination deck of Proto-Indo-European word roots for inspiration, making the album the fruit of an occult-tinged and antiquarian word game. Skelton also maintained the same restricted palette and duration for each piece, yet the tone varies significantly between them, as he treated each composition as a meditation upon a single, unvoiced question. To some degree, Four Workings is an especially ambient-minded release, as the hypnotically repeating melodic fragments are reminiscent of Celer's most loop-driven fare. The similarities mostly end there, however, as the billowing ambiance is often a smokescreen for a more sharp-edged and sophisticated undercurrent that slowly emerges from the murky depths. This is an unusually strong suite of compositions for Skelton's current phase, and the first piece in particular is probably among his finest moments to date.

This latest album from Skelton seems intended to be a major new statement, though not quite a formal follow-up to last year's These Charms May be Sung Over a Wound, as double LPs are a real rarity in the prolific composer's discography. If it was not intended as such, it certainly has the ambitious conceptual framework and focused power of his strongest work. For these four pieces, Skelton used a self-devised divination deck of Proto-Indo-European word roots for inspiration, making the album the fruit of an occult-tinged and antiquarian word game. Skelton also maintained the same restricted palette and duration for each piece, yet the tone varies significantly between them, as he treated each composition as a meditation upon a single, unvoiced question. To some degree, Four Workings is an especially ambient-minded release, as the hypnotically repeating melodic fragments are reminiscent of Celer's most loop-driven fare. The similarities mostly end there, however, as the billowing ambiance is often a smokescreen for a more sharp-edged and sophisticated undercurrent that slowly emerges from the murky depths. This is an unusually strong suite of compositions for Skelton's current phase, and the first piece in particular is probably among his finest moments to date.

The opening "[ ken- ] commencement" initially takes shape as a slow, sad melody of distorted string swells that languorously unfolds. Notably, however, the notes start to accumulate a shimmering wake with a sharp metallic edge. That element ultimately steals the show, as it merges with some deep drones around the piece's halfway point to blossom into a quavering crescendo of complex, bittersweet harmonies. It calls to mind a spectral orchestra playing an achingly beautiful slow-motion symphony of notes that lazily streak, quiver, and break apart. It is a damn-near perfect piece. The central melody, dreamily fluttering core, and frayed textures all combine to leave a deep and haunting impression. The following "[ aus- ] radiance" is a bit more billowing and soft-focused, evoking the flickering play of sunlight across a bank of dark, slow-moving clouds. The third piece ("[ aus- ] radiance") initially has the same aesthetic, but unexpectedly blooms into yet another album highlight. At times, it evokes a time-stretched recording of an organist soundtracking a silent horror film, but with a twist: the lovelorn organist unconsciously transforms everything into a wistful reverie. Gradually, it turns into an angelic yet steadily darkening haze that cocoons the oblivious organ melody. The closer ("[ ghē- ] releasement") takes more time than usual to get going. What begins as a glacially see-sawing pulse weaves through a fog of quietly roiling noise to become a hazily remembered/half-imagined ‘70s synthy space ambient album a la Tangerine Dream. While I wish that final piece was more of a dynamic culmination than a vaguely meditative comedown, the previous pieces admittedly set the bar unfairly high. If something like Four Workings is what results whenever Skelton makes up his own archeologically themed divination deck, I would see little incentive to abandon that strategy.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This double album had the misfortune of being released near the end of 2020, so it lamentably did not quite get the attention that it deserved (and being a live album probably did not help matters much either).  Granted, it has admittedly been a while since the NWW camp dropped an album that I would breathlessly proclaim a stone-cold masterpiece, yet the project's current era features quite a formidable lineup. In fact, most United Dairies/ICR releases in recent years have been refreshingly solid for an entity with such a vast and historically erratic discography. Barren happily continues that trend, documenting two performances from differing lineup configurations that have been deemed "amongst their most unusual performances." In this context, however, "unusual" means "very professional-sounding longform works conspicuously free of sinister whimsy." Significantly, the two performances are almost unrecognizable as NWW despite cannibalizing a pair of studio releases. They make for quite a satisfying deep-psych/spaced-out ambient release in their own right, however, as there is no rule stating that albums need to be representative to be enjoyable.

This double album had the misfortune of being released near the end of 2020, so it lamentably did not quite get the attention that it deserved (and being a live album probably did not help matters much either).  Granted, it has admittedly been a while since the NWW camp dropped an album that I would breathlessly proclaim a stone-cold masterpiece, yet the project's current era features quite a formidable lineup. In fact, most United Dairies/ICR releases in recent years have been refreshingly solid for an entity with such a vast and historically erratic discography. Barren happily continues that trend, documenting two performances from differing lineup configurations that have been deemed "amongst their most unusual performances." In this context, however, "unusual" means "very professional-sounding longform works conspicuously free of sinister whimsy." Significantly, the two performances are almost unrecognizable as NWW despite cannibalizing a pair of studio releases. They make for quite a satisfying deep-psych/spaced-out ambient release in their own right, however, as there is no rule stating that albums need to be representative to be enjoyable.

On the first disk, Steven Stapleton, Colin Potter, and Paul Beauchamp warp and deconstruct "Letter From Topor" & "Eyes Of A Scanning Girl" from [Sic] in a 2012 Florence concert. On the second, Andrew Liles replaced Beauchamp for a 2013 show in Karlsruhe that mangles "Opium Cabaret" from Terms and Conditions May Apply. The two pieces feel like they spring from the same vision, however, and that vision is one quite fond of extremely slow-burning psychotropic drones. More bluntly, that means both halves of this album take a while to catch fire, as it seems like the trio is recording, mixing, and subtly adding new layers in real time (the first disk is even called "Confluence"). As such, Barren demands some patience, as each drone-heavy performance seems to unfold on a supernaturally stretched time scale. In fact, Barren feels akin to a deep space ambient album a la The Magnificent Void, except there is a dimensional rift and a cacophony of lysergic bird songs, garbled voices, found-sound pile-ups, space crickets, exotic pop songs, and heavy electronic buzzes kept bleeding into the cold emptiness. The more eclectic second disk ("Transfiguration") is the stronger of the two and "Transfiguration 2" is probably the most stand-out piece on the album, as it follows the faint strains of a ghostly cabaret chanteuse into a shape-shifting mindfuck of smoky noir jazz and wah-wah-drenched desert psych oases. Both disks build into sufficiently surreal and vivid crescendos to justify their duration, however, as the overall trend is that each gets better and better as they unfold. Epic length aside, my only other caveat is that the all-enveloping drones dilute too much of NWW's essence to make this a crucial release by normal Stapleton standards. That said, it is nevertheless a very likable one-off plunge down a deep space rabbit hole, roughly resembling either a Black Stars-era Lustmord remix of a NWW album or its reverse.

Samples:

Read More