- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This second album from Milan-based visual artist/electro-acoustic composer Domiziano Maselli can be a disorienting collision of disparate inspirations at times, but it is certainly an intensely visceral and compelling experience when it hits the mark. Opal's description of the album mentions that Maselli possesses an "uncanny skill to create non-conformist drama," which feels like an apt characterization. It is similarly fair to say that Maselli likely has an extreme fondness for the gloomy prime of artists like Haxan Cloak and Raime, as well as a deep appreciation for Emptyset's seismic and intense approach to sound design. Elements of all three are certainly present on Lazzaro, though Maselli proves quite adept at building upon their best bits. That said, there are also a few pieces that radically break from the influences Maselli wears on his sleeve and they are uniformly brilliant. In one case, he approximates a massive contraption of slowly whirling jagged, rusted metal blades, while elsewhere he unleashes something akin to a demonically possessed string quartet hellbent on conjuring the darkest psychedelia. For me, Lazarro is a very strong album for those two pieces alone, but his execution for everything else is quite impressive as well.

This second album from Milan-based visual artist/electro-acoustic composer Domiziano Maselli can be a disorienting collision of disparate inspirations at times, but it is certainly an intensely visceral and compelling experience when it hits the mark. Opal's description of the album mentions that Maselli possesses an "uncanny skill to create non-conformist drama," which feels like an apt characterization. It is similarly fair to say that Maselli likely has an extreme fondness for the gloomy prime of artists like Haxan Cloak and Raime, as well as a deep appreciation for Emptyset's seismic and intense approach to sound design. Elements of all three are certainly present on Lazzaro, though Maselli proves quite adept at building upon their best bits. That said, there are also a few pieces that radically break from the influences Maselli wears on his sleeve and they are uniformly brilliant. In one case, he approximates a massive contraption of slowly whirling jagged, rusted metal blades, while elsewhere he unleashes something akin to a demonically possessed string quartet hellbent on conjuring the darkest psychedelia. For me, Lazarro is a very strong album for those two pieces alone, but his execution for everything else is quite impressive as well.

The opening "The Burrow" is the first of Lazzaro's two monster highlights, as it resembles a more malevolent and corroded sister to Eli Keszler's stellar Cold Pin album. It feels more like I am inside a vast, churning and scraping metal installation than like am hearing an electro-acoustic composition performed by a human, which is a neat trick. That said, there is evidence of Maselli's hand in some of the peripheral mindfuckery, as the mechanized intensity is enhanced by waves of seismic sub-bass, something resembling a flock of nightmarish birds, and some stammering and ravaged chords. At one point, I almost felt like I was aboard the Nostromo being menaced by skittering sounds from inside the walls. The following "A Desolation Chant" heads in a very different direction, approximating a soulful, reverberating sax solo in an empty parking garage. However, it often feels seem like the noirish sax licks transform into something menacing and sentient as they echo around their subterranean concrete environment, as there is a dark undercurrent of murky, gnarled dissonance and bass throb. Next, a brief interlude of storm sounds cleanses the palette for the album's second masterwork: the heaving and explosive string onslaught of "Gethsemane." While it has a haunted-sounding melodic motif at its core, the real magic lies in the violently sawing attack of the bow, the squealing harmonics, and the lysergic descending smears that appear in the background around the halfway point. To my ears, the epic two-part closer "Lazzaro" does not quite hit the same heights, but it is not a misfire either, as the diptych calls to mind a folk ensemble blearily emerging from a cave in the smoldering aftermath of the eschaton. That seems like a damn fitting way to end such a wonderfully blackened and intense album.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

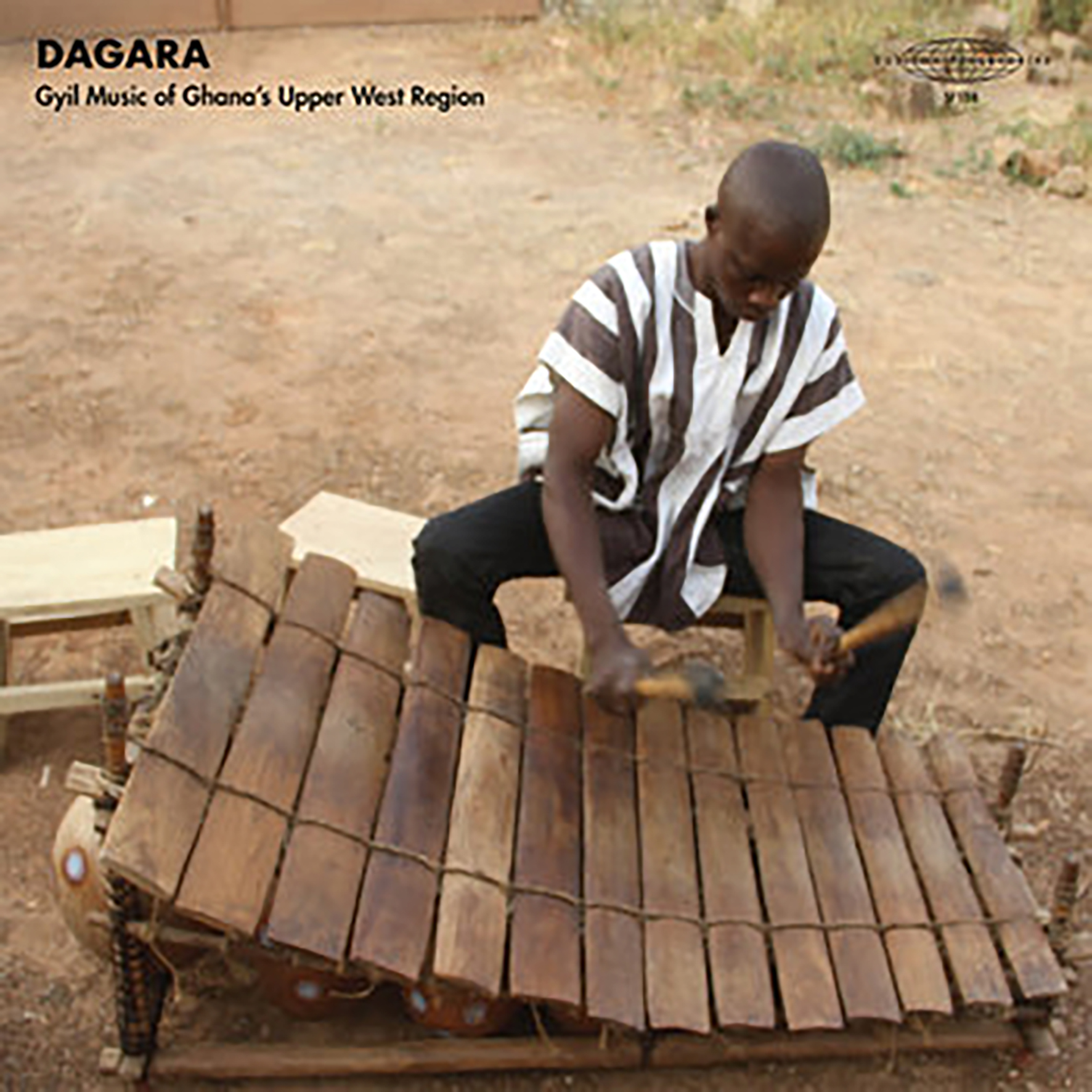

This mesmerizing and unique gem from Sublime Frequencies documents some killer field recordings made by Hisham Mayet in the Upper West region of Ghana back in 2019. I knew absolutely nothing about gyril music before hearing this album, but the most salient detail is that the primary instrument is a traditional xylophone used by the Lobi people. That does not even remotely convey how strange and wonderful these recordings are, but SF's description includes phrases like "long form trance music" and "acoustic techno," and those seem to hit the mark in spirit. To me, this album sounds like a ritualistic drum circle, but way more sophisticated, melodic, and psych-damaged than anything I would expect from actual communal percussion. As with a lot of field-recorded Sublime Frequency fare, it is very easy to dismiss this album as just an interesting window into an underheard culture from a cursory or casual listen. Once I listened to Dagara in a focused way, however, it quickly revealed itself to be something quite transcendent, as it seamlessly merges the otherness of great "experimental" music with an almost ecstatic visceral intensity.

This mesmerizing and unique gem from Sublime Frequencies documents some killer field recordings made by Hisham Mayet in the Upper West region of Ghana back in 2019. I knew absolutely nothing about gyril music before hearing this album, but the most salient detail is that the primary instrument is a traditional xylophone used by the Lobi people. That does not even remotely convey how strange and wonderful these recordings are, but SF's description includes phrases like "long form trance music" and "acoustic techno," and those seem to hit the mark in spirit. To me, this album sounds like a ritualistic drum circle, but way more sophisticated, melodic, and psych-damaged than anything I would expect from actual communal percussion. As with a lot of field-recorded Sublime Frequency fare, it is very easy to dismiss this album as just an interesting window into an underheard culture from a cursory or casual listen. Once I listened to Dagara in a focused way, however, it quickly revealed itself to be something quite transcendent, as it seamlessly merges the otherness of great "experimental" music with an almost ecstatic visceral intensity.

This album is ostensibly composed of two separate pieces that each span one side of vinyl, but the digital version is presented as a single 40-minute track, and the latter is exactly what it feels like. You can drop the needle anywhere on Dagara and roughly expect to get the same thing every time: vibrant percussion rhythms and unusual-sounding, interwoven xylophone melodies. That is primarily because no one piece of the puzzle stands out as particularly brilliant or memorable on its own. That said, the insanely complex web of overlapping rhythms and processed-sounding textures is legitimately amazing. And so is the way that the piece subtly and organically transforms like a dense cloud of migrating birds effortless shifting direction in perfect unison. It all cumulatively amounts to something psychedelic as hell, leading me to both envy whatever wavelength these cats are on AND marvel at how they managed to get there in perfect harmony. This is total hive mind, wheels-within-wheels territory in the best way. Beyond that, I would describe the overall aesthetic as "a tropical steel drum band went to India to study classical raga and Eastern spirituality and returned home completely unrecognizable and waaaaaay into psychedelics." That is a compliment (I would totally listen to such a band), but it also feels like that hypothetical band was then grist for a killer sound collage by a great tape artist. While I assume this was recorded entirely live, the smearing, deep vibraphone-like tones and the stammering, hesitating melodies sound alien and hallucinatory, similar to a serendipitous pile-up of unrelated loops locking gloriously in sync. There is much happening and all of it is interesting. In fact, I would be truly hard pressed to think of a "complex polyrhythm" opus from the 20th century avant-garde that could beat this ensemble at that game. Albums like this are exactly why I love Sublime Frequencies, as Dagara is a richly immersive tour de force of constantly shifting, interwoven patterns.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

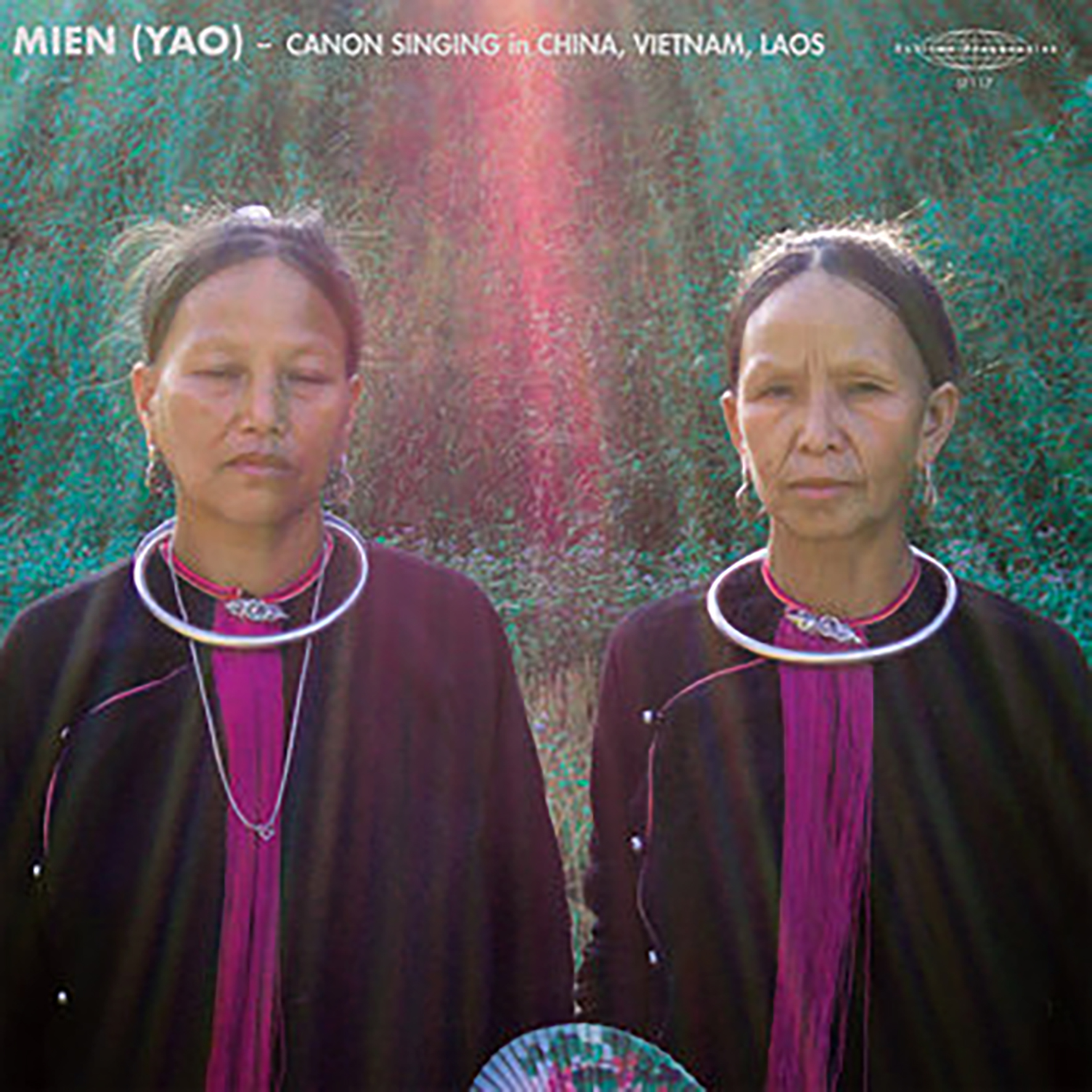

This collection of (mostly) acapella field recordings from Kink Gong's Laurent Jeanneau truly emphasizes the "sublime" part of the Sublime Frequencies vision, as this is quite an eerily lovely and mesmerizing album. While the recordings span three different countries (China, Laos, and Vietnam), they are all roughly rooted in a single cultural milieu: the Chinese hill tribes known pejoratively as the Yao ("dog" or "savage"). Understandably, a large number of these tribal folk prefer the name Mien ("people"), but they are a multifarious bunch that have spread beyond China into Southeast Asia and evolved into numerous distinctive and divergent subcultures. The first half of the album is devoted to very pure and simple canon singing ("an initial melody is imitated at a specified time interval by one or more parts"), while the second half offers some compelling and more fleshed-out variations. While the "raw, ethereal, and cosmic" performances that Laurent captured need no additional enhancement to captivate me, the variations are every bit as great as the undiluted essence and give the album an impressively strong dynamic arc.

This collection of (mostly) acapella field recordings from Kink Gong's Laurent Jeanneau truly emphasizes the "sublime" part of the Sublime Frequencies vision, as this is quite an eerily lovely and mesmerizing album. While the recordings span three different countries (China, Laos, and Vietnam), they are all roughly rooted in a single cultural milieu: the Chinese hill tribes known pejoratively as the Yao ("dog" or "savage"). Understandably, a large number of these tribal folk prefer the name Mien ("people"), but they are a multifarious bunch that have spread beyond China into Southeast Asia and evolved into numerous distinctive and divergent subcultures. The first half of the album is devoted to very pure and simple canon singing ("an initial melody is imitated at a specified time interval by one or more parts"), while the second half offers some compelling and more fleshed-out variations. While the "raw, ethereal, and cosmic" performances that Laurent captured need no additional enhancement to captivate me, the variations are every bit as great as the undiluted essence and give the album an impressively strong dynamic arc.

The opening "Lan Pan Moon" is a haunting and chant-like duet between two Laotian women (Keo and Na) centered upon a droning root tone. While the piece could not be much more simple melodically, the two women achieve an otherworldly beauty in the way they harmonize around the hypnotically cyclical motif. In fact, it feels akin to a harmonic dance, as the two voices keep diverging then reconverging into quavering unison, and the whole thing feels akin to a Lucier-ian feat of phase manipulation. The following "Kai Tian Pi Di" is a similarly unaccompanied duet (from China this time), but it shares some common stylistic ground with old African American work songs (there is even some bluesy note-bending). The album's second half kicks off with another piece from China, but it seems like an especially virtuosic version of the form, as the lead voice embellishes the central melody with a host of unusual bends, stammers, and ululation-like flourishes. The closing "Dao Cham" (from Vietnam) is still more divergent, however, as the heart of the piece is the clanging and rattling percussion of a lively ritualistic street procession. Gradually, the voices of the singers grow more prominent, yet the real beauty of the piece lies in how the various voices (singing and otherwise) lysergically drift in and out of focus. While I am not sure how intentional that was on Jeanneau's part, I certainly enjoy the effect, as it nicely blurs the line between field recording and sound collage. Due to the propulsive rhythm, the metallic physicality of the cymbals, and the surprise psychedelic elements, "Dao Cham" is my personal favorite on the album, but every single one of these pieces could be a revelation for adventurous ears.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

1988's Love Hysteria was my introduction to Peter Murphy as a solo artist, likely initiated by MTV's 120 Minutes airplay of "All Night Long." A minor hit in the United States, this and a host of other strong tracks from Murphy's second solo release would see Murphy exposed to a renewed audience as a solo performer, those both unfamiliar and familiar with his back catalog. Some of this may be attributable to the start of Murphy's songwriting collaboration with Paul Statham (ex B-Movie). This fruitful union would see the two working together for another six albums, producing some of his best-loved works over the next few years. This work alone spawned the aforementioned "All Night Long" as well as masterworks "Indigo Eyes," "Dragnet Drag," and "Blind Sublime."

1988's Love Hysteria was my introduction to Peter Murphy as a solo artist, likely initiated by MTV's 120 Minutes airplay of "All Night Long." A minor hit in the United States, this and a host of other strong tracks from Murphy's second solo release would see Murphy exposed to a renewed audience as a solo performer, those both unfamiliar and familiar with his back catalog. Some of this may be attributable to the start of Murphy's songwriting collaboration with Paul Statham (ex B-Movie). This fruitful union would see the two working together for another six albums, producing some of his best-loved works over the next few years. This work alone spawned the aforementioned "All Night Long" as well as masterworks "Indigo Eyes," "Dragnet Drag," and "Blind Sublime."

Sometimes, writing a review about one's revered musicians can be a struggle, challenging as it may be to separate one's memories of a much-loved album with time and place. As I transitioned from high school to college, the dawn of the nineties was approaching, and the familiarities I'd felt growing up in the eighties seemed to be fading. New music, shifting places, different friends, and the loss of a certain comfort was on the horizon as I completed my last year of high school. This era felt ripe for the birth of a massive amount of new music, but I felt a need for stability and nostalgia as life marched on into unknown directions. The darker, romantic music I had embraced in high school that had such an impact on my life seemed to be changing, not always for the better, and I felt a longing for something I couldn't quite put my finger on. I was thus relieved when seeing 120 Minutes' airing of "All Night Long," an artist I was familiar with and that, up to that point, was not aware had embarked on a solo career. I instantly liked the song, so I went to pick up the vinyl at a local record shop, albeit with some trepidation.

Produced by former Fall member Simon Rogers (another band I had only recently become familiar with), the album opens with the instantly endearing "All Night Long," the sultry sound of Murphy's vocals and marimba introducing the album. Along with Paul Statham, Murphy's backing band The Hundred Men comprised a tight cast, including Matthew Seligman (Soft Boys, Thompson Twins, Thomas Dolby), as well as a repeat appearance from Howard Hughes. There's an evident songwriting maturity from Should the World Fail to Fall Apart, with lyrics showcasing far more abstract poetry than the former yet don't require profound interpretation for enjoyment. "All Night Long" and "His Circle and Hers Meet" feel like unabashedly personal love songs.

While much of the album tends towards a more ethereal bent, Murphy and team show they can rock out. "His Circle and Hers Meet" is one of the most straightforward rockers of his catalog, the others being "Blind Sublime" and the closing cover of Iggy Pop's "Funtime." Yet, this by no means indicates the rest of the album is sleepy dream pop. With the new songwriting duo and the Hundred Men in place, the talented band surges forth with combined rock power, acoustic atmosphere, and mystical rhythms, enhancing Murphy's rich baritone vocals. "Dragnet Drag" bursts forth with powerful percussion and inspired melody, building to a powerful chorus imploring listeners that "Hell is not the fire, Hell is your belief in yourself as the higher." The questioning "Indigo Eyes" kicks off with shimmering acoustic guitar and a melody to match, "With grey desire, he looks out mad with soft grey indigo eyes," another standout track of the album. A dreamy keyboard intro to "Time Has Got Nothing to Do With It" builds, along with Murphy's powerful vocal stylings. By the time he emphatically implores, "Time has go nothing to do with it," it doesn't matter what the interpretation of the song might be; it just feels like something utterly powerful. Poetic license is extensive across the album, but the powerful melodies and Murphy's intense vocal stylings make for an immersive listening experience.

The reissue offers no extra tracks and repeats the same running order as the original. A double-disc was released back in 2013 with largely non-essential demos. Hear the album here as intended, pressed on gorgeous indigo vinyl, preferably through a set of good headphones.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

As his primary (and solo) project, Albany’s Eric Hardiman's Rambutan is always in flux. Some of his many other projects are a bit more predictable: Sky Furrows is 1980s indie noise rock inspired, Spiral Wave Nomads is more free improvisation, etc., but Rambutan has always been something different. Sometimes the work is harsher, other times more subdued and atmospheric, and instrumentation can very significantly from release to release. For this more conceptually album, there is even less predictability. Featuring 69 contributing artists across 33 pieces and over two and a half hours in length, it is fully encompassing of Hardiman’s body of work, solo and in collaboration with others, and reiterates what a multifaceted and gifted artist and performer he is.

As his primary (and solo) project, Albany’s Eric Hardiman's Rambutan is always in flux. Some of his many other projects are a bit more predictable: Sky Furrows is 1980s indie noise rock inspired, Spiral Wave Nomads is more free improvisation, etc., but Rambutan has always been something different. Sometimes the work is harsher, other times more subdued and atmospheric, and instrumentation can very significantly from release to release. For this more conceptually album, there is even less predictability. Featuring 69 contributing artists across 33 pieces and over two and a half hours in length, it is fully encompassing of Hardiman’s body of work, solo and in collaboration with others, and reiterates what a multifaceted and gifted artist and performer he is.

For Parallel Systems, Hardiman solicited a multitude of participants: friends, collaborators, and personal heroes, to submit recorded contributions that he collaged and blended over the past two years. There are a vast array of collaborators here: representatives from the local Upstate New York/Western Massachusetts scene (Mike Bullock, Rob Forman, Mike Griffin, Matt Weston, plus more), some legendary noise artists (Anla Courtis, John Olson, Howard Stelzer), and even the likes of Guy Picciotto of Fugazi/Rites of Spring, Mission of Burma’s Peter Prescott, and Mike Watt.

The liner notes list what artists contribute to what songs, but even with Hardiman's intentional avoidance of over-processing the recordings, who is contributing what is not always clear.In some instances it is somewhat obvious:Hardiman's partner in Spiral Wave Nomads Michael Kiefer appears on drums for multiple pieces, and Mike Bullock’s upright bass playing is rather distinct as well.Karen Schoemer, of Sky Furrows, contributes some obvious spoken word as well, although the songs that she appears on are far less rock-like in their execution compared to that project.

Regardless of who is doing what, the music runs the gamut across these two CDs."System 2" is an excellent paring of idling hums and distorted, fuzzy melodies.Drums delicately punctuate the pleasant distortion and melody that snakes through he mix.For "System 14," Hardiman blends a backwards melody and crunchy abstractions with conventional bass, building layer upon layer into a strange combination of noise and structure."System 6" also blends a sense of chaos with structure via mutated sounds, metronomic drumming, and lovely distorted bass guitar.

Other pieces sit more closely in either the noise or music ends of the spectrum.The droning buzzes and found sounds of "System 15" make for a slightly unsettling and harsher experience, while the overdriven, sputtering tapes and fragments of what sounds like a metal band’s rehearsal cut in and out of the collage heavy "System 25," which comes across as intentionally disjointed, but somehow works perfectly.On the other hand, "System 7" is a mass of clattering sounds and what sounds like far off drum machine, but the rhythm, bass, and synths that appear morph into a unique, but clear form of melody."System 20" is surprisingly traditional, with liquid bass guitar and distinct drumming coming together in a taut piece of dubby funk that make for a piece that stands out distinctly.

With so many artists and so much material on Parallel Systems, it is a lot to take in, but covering so many different styles and structures, it never feels like too much.Having the liner notes specify who contributes to which pieces certainly leads to the desire to identify who is doing what, but this certainly is not a case where the concept of the record outlines its content.Hardiman's approach of collage, rather than processing, those contributions is perfect since it results in the equal contribution of the participants, as well as his own, to the end product.Perfectly encapsulating the diversity of his own work, Hardiman's brilliance certainly does not take a backseat to this multiple collaborators but instead shines through even brighter. It is simply an amazing work on a massive scale that I find something new in each time I listen to it.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This solo drone project from Ulan Bator's Amaury Cambuzat has been one of my favorite discoveries of the last few years, as both AmOrtH and W featured moments that induced me to proclaim that Cambuzat was "a goddamn drone shaman." This latest album was a bit of a surprise, however, as Cambuzat casually made it available as a digital-only release on his Bandcamp page with just a simple description of "This is the very first recording of I Feel Like a Bombed Cathedral." Apparently, the recordings date from early 2018 and I am amazed that Cambuzat did not feel inclined to make them public until now, as a handful of these pieces are absolute gems that rank among the project’s finest work. A few of the other ones admittedly feel like a searching, partially formed vision of the greatness to come, but γένεσις is much, much better than its humble "vault clearing" origins suggest. I would not have been at all disappointed if this was a proper new Bombed Cathedral release, as the album is absolutely teaming with beautifully warped guitar sounds and immersive layers of richly textured psychedelia. In fact, γένεσις only heightens my expectations for whatever Cambuzat might be working on now, as no sane person would keep music this great on the shelf for three years unless they had something even better in the pipeline.

This solo drone project from Ulan Bator's Amaury Cambuzat has been one of my favorite discoveries of the last few years, as both AmOrtH and W featured moments that induced me to proclaim that Cambuzat was "a goddamn drone shaman." This latest album was a bit of a surprise, however, as Cambuzat casually made it available as a digital-only release on his Bandcamp page with just a simple description of "This is the very first recording of I Feel Like a Bombed Cathedral." Apparently, the recordings date from early 2018 and I am amazed that Cambuzat did not feel inclined to make them public until now, as a handful of these pieces are absolute gems that rank among the project’s finest work. A few of the other ones admittedly feel like a searching, partially formed vision of the greatness to come, but γένεσις is much, much better than its humble "vault clearing" origins suggest. I would not have been at all disappointed if this was a proper new Bombed Cathedral release, as the album is absolutely teaming with beautifully warped guitar sounds and immersive layers of richly textured psychedelia. In fact, γένεσις only heightens my expectations for whatever Cambuzat might be working on now, as no sane person would keep music this great on the shelf for three years unless they had something even better in the pipeline.

I have no idea if the opening "Te Deum" was the birth of this project or not, but it certainly does a hell of a job at conjuring up images of a recently bombed cathedral, as the organ-like tones of Cambuzat's guitar feel like rays of sunlight passing through thick smoke and stained glass (a feeling further enhanced by the deep, elegiac chord progression beneath). It is extremely brief, so it does not rank as an album highlight, but there are at least four other pieces that do. The first admittedly takes a while to get going, as "Tibi Omnes" devotes two minutes to a single sharp feedback-like tone that flickers like a candle. Fortunately, it then spends the next fourteen minutes blossoming into a beautiful, dreamlike vision of a mass in an ancient cathedral that has caught in a film projector and begun to burn and bubble in slow motion. The following "Dignare" gamely continues the "organ-like guitar tones collide with the distending fabric of reality" theme with great success. It roughly approximates the organ accompaniment to a silent gothic horror film, but slowed way down until it bleeds into itself while the projector erratically warps the film. Later "Te Ergo Quaesumus" continues another big theme ("nightmarishly crystalline approximations of a pipe organ"), but also sounds like wind chimes played back at such an extremely slow speed that everything is in a grainy, smeared state of suspended animation. I suppose the closing "γένεσις" could be the true first Bombed Cathedral piece given its name, but I would be surprised, as it is the most brilliant and sophisticated one on the album. It calls to mind a demonic calliope that acts as a nightmare machine, as "wrong" notes in the melody keep lingering to form sickly, infernal harmonies. All of that amounts to an impressively solid album, but anyone who digs Cambuzat's work will absolutely want to hear that title piece, as it is unquestionably a career highlight of some kind.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

Back in 2016, noise/sound art legend Joe Colley returned from a lengthy hiatus to release the solid No Way In on Jason Lescalleet's Glistening Examples, but he has been extremely quiet ever since, surfacing only to release a tape of a durational live performance last year. Happily, he is back again with another major statement and it is quite a monster. It is also unusually accessible at times, as Trance Tapes lives up to its name beautifully (though those trances inevitably curdle into nightmare territory). In some ways, this album resembles a classic noise tape on the more "industrial" side of the spectrum, as each of the four pieces is built from a foundation of relentless, obsessively repeating "machine-noise" to varying degrees. That is merely the starting point, however, as each piece rapidly blossoms into a vividly psychotropic mindbomb of viscerally buzzing frequencies and hypnotically repeating chirps, bleeps, throbs, and looping drones. I suspect many serious noise fans would roll their eyes or spit out their drink in disbelief if I had the temerity to proclaim this a career highlight, so I will refrain from doing that. However, it is extremely difficult to imagine a Joe Colley or Crawl Unit album in which he was able to realize his vision with more clarity and focus than he does with this near-perfect tour de force.

Back in 2016, noise/sound art legend Joe Colley returned from a lengthy hiatus to release the solid No Way In on Jason Lescalleet's Glistening Examples, but he has been extremely quiet ever since, surfacing only to release a tape of a durational live performance last year. Happily, he is back again with another major statement and it is quite a monster. It is also unusually accessible at times, as Trance Tapes lives up to its name beautifully (though those trances inevitably curdle into nightmare territory). In some ways, this album resembles a classic noise tape on the more "industrial" side of the spectrum, as each of the four pieces is built from a foundation of relentless, obsessively repeating "machine-noise" to varying degrees. That is merely the starting point, however, as each piece rapidly blossoms into a vividly psychotropic mindbomb of viscerally buzzing frequencies and hypnotically repeating chirps, bleeps, throbs, and looping drones. I suspect many serious noise fans would roll their eyes or spit out their drink in disbelief if I had the temerity to proclaim this a career highlight, so I will refrain from doing that. However, it is extremely difficult to imagine a Joe Colley or Crawl Unit album in which he was able to realize his vision with more clarity and focus than he does with this near-perfect tour de force.

"Program One" kicks off the album with insistent, rapid pulses of machine-like hum that initially feel like a locked groove, but rapidly begin accumulating both momentum and layers of killer mindfuckery. By the time the piece is even one-third through, it has blossomed into a nightmare of gibbering, squirming, and clicking insectoid cacophony. It then dissolves into a throbbing and otherworldly coda of futuristic electronic chirps that accumulate high frequencies that make the air vibrate and my brain buzz. That sensation is an extremely familiar one with Trance Tapes, as Colley is quite adept at luring me into a numbed state with mechanical repetition while sneakily unleashing high frequencies that will relentlessly drill deeper and deeper into my consciousness. Anyone who makes it through that entire song at reasonably high volume will absolutely feel slightly insane by the end. I mean that as a compliment, but I suspect a person could easily be convinced that this tape was leaked from some secret CIA black ops project involving the weaponization of high frequencies.

"Program Two" gleefully keeps those more brain-burrowing frequency attacks coming (sharper than ever!), but also feels like an army of wind-up toys showed up as well. It is the album's greatest endurance test, but I feel like I am the one at fault for being too mentally weak to withstand the full force of Colley's merciless sensory assault. The second half is thankfully a bit less malevolently sanity-eroding, yet it is every bit as good. "Program Three" resembles a vast futuristic field of hissing sprinklers and robot lawnmowers that grows progressively more smeared and buzzy, while "Program Four" sounds like a couple of '70s synth guys attempting to mimic a (psychedelic) frog pond at night. Surprisingly, that final piece is almost semi-melodic at times, like a small but sweet reward for joining Colley in such a deep plunge down an oft-disturbing rabbit hole.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

It admittedly took me a while to finally connect all the dots in my head, but it dawned on me recently that The Boats were kind of the Throbbing Gristle of a hard-to-define strain of ambient-adjacent bittersweet melancholia. My case: both Andrew Hargreaves and/or Craig Tattersall have been consistently involved in a host of varied and wonderful projects for more than two decades now (Hood, The Remote Viewer, Tape Loop Orchestra, etc.). The tape loop-focused The Humble Bee is Tattersall's most prolific and consistent endeavor; he has been releasing solo work and collaborations under that moniker since 2009. In fact, this album was the project's debut, but I only recently heard it for the first time, as its initial release was a limited CDr in a handmade case made from repurposed book covers (pictured). Last month, it got a well-deserved reissue on vinyl from the endearingly eccentric Astral Industries with VERY different cover art and it sold out instantly. That gives me hope for humanity, as this incredibly beautiful and absolutely sublime release deserves as much exposure as it can get. A Miscellany for the Quiet Hours is a stone-cold classic.

It admittedly took me a while to finally connect all the dots in my head, but it dawned on me recently that The Boats were kind of the Throbbing Gristle of a hard-to-define strain of ambient-adjacent bittersweet melancholia. My case: both Andrew Hargreaves and/or Craig Tattersall have been consistently involved in a host of varied and wonderful projects for more than two decades now (Hood, The Remote Viewer, Tape Loop Orchestra, etc.). The tape loop-focused The Humble Bee is Tattersall's most prolific and consistent endeavor; he has been releasing solo work and collaborations under that moniker since 2009. In fact, this album was the project's debut, but I only recently heard it for the first time, as its initial release was a limited CDr in a handmade case made from repurposed book covers (pictured). Last month, it got a well-deserved reissue on vinyl from the endearingly eccentric Astral Industries with VERY different cover art and it sold out instantly. That gives me hope for humanity, as this incredibly beautiful and absolutely sublime release deserves as much exposure as it can get. A Miscellany for the Quiet Hours is a stone-cold classic.

Cotton Goods/Astral Industries

Given the literary/antiquarian bent of the original packaging, "The Bedside Book" fittingly opens the album on a note of dreamily flickering, sepia-toned wistfulness. It conjures an understatedly gorgeous pile-up of frayed, overlapping, and gently crackling antique music box loops. The hits just keep coming from there, as Tattersall ingeniously weaves sparse melodic fragments into richly textured and sometimes achingly beautiful collages that feel like the work of an enchanted Victrola. I realize that the magic of this album is simply "Craig Tattersall has a great ear for loops and is extremely skilled at collaging them in interesting, soulful ways." However, it is still a genuinely surprising and improbable convergence of different threads. It sometimes seems like Mary Lattimore recorded source material for Everyone Alive Wants Answers–era Colleen, but then Philip Jeck cannibalized their album and teamed up with a jazz guy for an impressionistic and understated accompaniment to a night of classic silent film. In less convoluted terms, that means that Tattersall uses a lot of simple, but lovely harp-like melodies that pop, crackle, and warble in pleasantly languorous fashion, but sometimes a double bass or a trumpet will steer things in a more sensual or noir direction. The album highlight is probably "Technical Press," which punches up Tattersall's already beautiful vision with a cool bass loop and plenty of wobbly and warped psychedelic flourishes. Elsewhere, "With Answers" makes similarly effective use of backwards sounds, but in more throbbing, ambient-minded fashion, while the closing "P209" feels like a killer dub techno classic that's been frayed and hiss-ravaged into something a bit more hypnagogic. While those four pieces are currently my favorites, competition is unusually fierce, as Tattersall's instincts are absolutely unerring on this album.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Should the World Fail to Fall Apart finds Murphy not entirely moving away from the entanglements of his former group, elaborating on the musical styles explored in Dalis Car. The musical stylings of his debut were problematic for me on its original release, enamored as I was of Bauhaus. Still, over the years, it has grown to become one of my personal favorites of his solo works despite it often being deemed one of his less worthy offerings. The album is reminiscent of a transition period, but the reissue is a reminder of his brilliance.

Should the World Fail to Fall Apart finds Murphy not entirely moving away from the entanglements of his former group, elaborating on the musical styles explored in Dalis Car. The musical stylings of his debut were problematic for me on its original release, enamored as I was of Bauhaus. Still, over the years, it has grown to become one of my personal favorites of his solo works despite it often being deemed one of his less worthy offerings. The album is reminiscent of a transition period, but the reissue is a reminder of his brilliance.

On his debut, Murphy continues to take cues from the romantics through passionate vocal delivery, lyrics, and melody, toning down the Bowie influence but maintaining a dramatic delivery. While he would gain a wider solo audience with Love Hysteria and Deep, it's astounding a man not yet out of his twenties seems a wiser and more practiced fifties, further supported by a fantastic cast of musicians. Guitar work from former bandmate Daniel Ash, Turkish fretless master Erkan Oğur, and co-producer Howard Hughes bring strength to the tracks, with Magazine's own John McGeoch providing guitar on Murphy's inspired cover of "The Light Pours Out of Me," with the interpretation of Pere Ubu's "Final Solution" only somewhat less inspired. A driving bassline from Eddie Branch is the central force behind "Blue Heart." Former bandmate Daniel Ash provides indeed "manic" guitar on "The Answer is Clear" over tribal drum programming and sweeping orchestral arrangements.

Yet, it is the Murphy-penned tracks that reveal him as a maturing songwriter. He touches on his aging in "Confessions" and the pitfalls inherent in using one's image to sell music. "Lyrics sung from pretty looks / Can on the reader feed / Be strong to check and recognize / The pretty face is all / But being used to sell you songs / That never say it all." "God Sends" is more than a memorable melody, encouraging the listener to stop looking for a "superstar" outside of oneself and find the one within. "Tell my friends they're all potential / They're all potential Godsends." "Jemal" is based on a traditional du'a (prayer) in Islam that seeks peace for all things, backed by gorgeous piano. Turkish lyrics "Nefret olan yere sevgi, yaralanma olan yere affedicilik / Kuşku olan yere inanç, ümitsizlik olan yere ümit" translate to "Love where there is hate, forgiveness where there is injury / Faith where there is doubt, hope where there is despair," echoing the Sufi tradition of contradiction in prayer.

Murphy doesn't discard his past entirely but cleverly reminds listeners that new beginnings are afoot. He has long been a wordsmith, crafting stories amongst a poetic backdrop. The album's title track provides a circuitous path between lack of sleep, smoking ruins, and never men: "Can't hear for lack of sleep / Breathing in the smoking ruins / The rockets in the shadows whispering / Singing in the underground / Love and the never men / Can't hear for lack of sleep." The track immediately following, "Never Man," maintains some of his musical past with its ominous melody and background of haunting vocals, tieing the never man back to the preceding track and smoking ruins, continuing a story for the listener to untangle. "The love of the Never man / Can't breathe for smoking ruins / Third eye glimpses a second thought / Is blocked and returns / Can't breath for smoking ruins / Contains a story he / Never being heard / When better days will mean / Can't breath for smoking ruins Love of the Never man / Jumps through the blackest heat."

This reissue offers no new tracks, choosing instead to align to the original release. A good turntable and stereo system will showcase the lush production of John Fryer (This Mortal Coil) pressed to blue vinyl. While this release may not be a universal fan favorite, it displays the talent from which Murphy came and the creativity he would continue to evolve.

Many thanks to my friend and uberfan Chris Mason for assistance.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This is the debut album from a Berlin-based foursome dedicated to performing the works of Malaysian-born composer/trombonist Rishin Singh. Notably, Singh is also a member of Konzert Minimal, which is a modern classical ensemble dedicated to performing compositions by the Wandelweiser collective. In a 2016 New Yorker profile of the Wandelweiser milieu, Alex Ross noted that one recurring theme in their work is a "ghost tonality never achieves stability; it will frustrate those who expect one chord to lead logically to another." Singh's own vision shares a lot of similar stylistic terrain, as A Fog Like Liars Loving is nothing if not ghostly (and creepy (and unsettling)). It resembles an alternate universe version of Low in which they were a chamber music ensemble that listened to a steady diet of nothing but Jandek, Scott Walker, Marble Index-era Nico, and warped old folk records played at the wrong speed. That said, Singh definitely has an unusually sophisticated sensibility regarding dissonant harmonies and the entire album has an eerily nocturnal, dread-soaked, and somnambulant feel that is uniquely Leider's own. Purportedly, the album also features an "understated gallows humor," which is also an achievement of sorts, as Singh has managed to cultivate a strain of black humor so bleak that even I often have a hard time detecting it.

This is the debut album from a Berlin-based foursome dedicated to performing the works of Malaysian-born composer/trombonist Rishin Singh. Notably, Singh is also a member of Konzert Minimal, which is a modern classical ensemble dedicated to performing compositions by the Wandelweiser collective. In a 2016 New Yorker profile of the Wandelweiser milieu, Alex Ross noted that one recurring theme in their work is a "ghost tonality never achieves stability; it will frustrate those who expect one chord to lead logically to another." Singh's own vision shares a lot of similar stylistic terrain, as A Fog Like Liars Loving is nothing if not ghostly (and creepy (and unsettling)). It resembles an alternate universe version of Low in which they were a chamber music ensemble that listened to a steady diet of nothing but Jandek, Scott Walker, Marble Index-era Nico, and warped old folk records played at the wrong speed. That said, Singh definitely has an unusually sophisticated sensibility regarding dissonant harmonies and the entire album has an eerily nocturnal, dread-soaked, and somnambulant feel that is uniquely Leider's own. Purportedly, the album also features an "understated gallows humor," which is also an achievement of sorts, as Singh has managed to cultivate a strain of black humor so bleak that even I often have a hard time detecting it.

I never would have guessed on my own that this album was written by a male trombonist, as the most prominent threads that run throughout these songs are the dual female vocals of Annie Gårlid and Stine Sterne, the moaning strings, and the curdled, murky flutes. All are abundant in the creeping fog of dread and hanging dissonance that is the opening "The Weeping Wound," but the quartet's blurred gloom is also imbued with a sense of insistent (if glacial) forward motion by a simple drum machine pattern. Ironically, it is often that minimal drum machine element that determines how well a song works, as the compositions themselves are so purposely wraithlike and alienating that even the slightest rhythm feels like a welcome injection of life and physicality (akin to a still-beating heart faintly thumping within a corpse). When that beat disappears, Leider approximate a traditional folk ensemble from an earlier era that has been exhumed, reanimated, and handed rotted, mis-tuned instruments…and then asked to envision what The Wicker Man soundtrack would sound like if it had been an Ingmar Bergman film. That said, one of those beatless pieces is arguably the album's bleakly compelling centerpiece, as "Great Expectations" transforms a few lines of Dickens into a menacing dirge that erupts into a visceral, squealing catharsis. "Colder Underground" is another dirge/highlight, calling to mind a time-stretched Celtic folk ensemble accompanied by a slowly beating heart. It even has a hook, as the repeating refrain of "do you find it funny?" is surprisingly catchy and also feels like the final thing I might hear before being murdered by a coven of forest witches. I suspect I would probably like the rest of the album considerably more if it were less relentlessly dour (it makes for difficult entertainment), but Singh's focused vision feels like a promising success as art, as I can easily imagine an installation based on this album being a macabre sensation at a contemporary art museum.

Samples can be found here.

Read More