- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

Four years in the making, this inaugural release from Brooklyn composer Nayar is something of a small, genre-blurring masterpiece that brings together stuttering, laptop-mangled melodies a la early Fennesz and Oval with billowing ambient warmth. Our Hands in the Dark is a bit more inventive and distinctive than a hazy and heavenly homage to the golden age of Editions Mego and Mille Plateaux, however, as it also features some unexpected nods to Rilke, classic Midwestern emo, and Indian mysticism along the way. To some degree, I am the target demographic for all of those things, but this album is wonderful primarily because of Nayar's oft-brilliant execution, as these eight songs are a veritable feast of exacting craftsmanship, tight songcraft, vivid textures, warm harmonies, and immersive atmospheres. If this album had come out twenty years ago, it likely would have become a regularly name-checked cornerstone of the laptop/experimental guitar scene. Since it is coming out now instead, I suppose it will just have to settle for the consolation prize of being an early contender for one of 2021's strongest debuts.

Four years in the making, this inaugural release from Brooklyn composer Nayar is something of a small, genre-blurring masterpiece that brings together stuttering, laptop-mangled melodies a la early Fennesz and Oval with billowing ambient warmth. Our Hands in the Dark is a bit more inventive and distinctive than a hazy and heavenly homage to the golden age of Editions Mego and Mille Plateaux, however, as it also features some unexpected nods to Rilke, classic Midwestern emo, and Indian mysticism along the way. To some degree, I am the target demographic for all of those things, but this album is wonderful primarily because of Nayar's oft-brilliant execution, as these eight songs are a veritable feast of exacting craftsmanship, tight songcraft, vivid textures, warm harmonies, and immersive atmospheres. If this album had come out twenty years ago, it likely would have become a regularly name-checked cornerstone of the laptop/experimental guitar scene. Since it is coming out now instead, I suppose it will just have to settle for the consolation prize of being an early contender for one of 2021's strongest debuts.

The album's lead single "The Trembling of Glass" is an interesting piece, as it immediately made me want to hear the album, yet does not quite capture Nayar's aesthetic at its most distinctive and seamlessly executed. The fact that her influences are so readily displayed ("killer early 2000s laptop guitar album dissolving into American Football-style arpeggios") does not diminish my enjoyment though, as the churning, chopped, stammering, and unpredictable guitar loops of the first two minutes are absolutely gorgeous. To my ears, however, the album fitfully blossoms into something even better and more unique as it unfolds. For example, "Losing Too Is Still Ours" follows the same "one thing transforms into another" theme of the opener, but the motifs are a bit more radical. It starts with a shimmering, flickering bed of processed guitars joined by some intense and haunting wordless vocals from guest Yatta, then evolves into a second act that resembles a chopped, fluttering, and beautifully poignant orchestral loop playing over some unusually warm, shoegaze-damaged space ambient. That piece is definitely a highlight, but there are several others that reach similar heights. In fact, I am probably most fond of the pair of pieces that close out the the album. The first is the epic-feeling "Aurobindo," which blends dreamy synths; a lovely arpeggio progression; swooning, reverb-swathed vocals; and a host of flickering, hissing, and gently warped sounds into a shape-shifting gem of reality-blurring psychedelia. The closing "No Future," on the other hand, sounds like an achingly beautiful cello melody from Zeelie Brown being violently and repeatedly mashed together with I'm Happy, And I'm Singing by a malfunctioning computer before giving way to a lovely and tender coda of unexpectedly unmangled piano. Aside from being a great piece, "No Future" is an especially illustrative example of why Nayar's vision is so instantly and deeply appealing: she excels at finding the precarious nexus where sophisticated avant-garde sensibilities mingle with simple, lovely melodies and genuine human warmth.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I believe this is my first encounter with this London-based cellist/composer, but that is hardly surprising, as Die Schachtel often tends to be ahead of the curve in unearthing compelling new sound art. As befits the Decay series' mission statement of highlighting "inspired contemporary experimental efforts in ambient, ethereal, and emotively abstract music," Reuben is an album of hazy, dreamlike soundscapes that feel like they were assembled from hissing and blurred tape loops (though I do not believe they were). Regardless of how it was assembled, this is quite an immersive and fitfully gorgeous album, as Mussida displays an impressive lightness of touch, talent for nuanced detail, and a deep understanding of the physics of sound. And it certainly does not hurt that he made full use of the rich acoustic properties of Volterra, Italy's historic Church of San Giusto.

I believe this is my first encounter with this London-based cellist/composer, but that is hardly surprising, as Die Schachtel often tends to be ahead of the curve in unearthing compelling new sound art. As befits the Decay series' mission statement of highlighting "inspired contemporary experimental efforts in ambient, ethereal, and emotively abstract music," Reuben is an album of hazy, dreamlike soundscapes that feel like they were assembled from hissing and blurred tape loops (though I do not believe they were). Regardless of how it was assembled, this is quite an immersive and fitfully gorgeous album, as Mussida displays an impressive lightness of touch, talent for nuanced detail, and a deep understanding of the physics of sound. And it certainly does not hurt that he made full use of the rich acoustic properties of Volterra, Italy's historic Church of San Giusto.

It makes perfect sense that Rueben was recorded in an old church, as the warm, languorous drones of the opener are certainly evocative of a picturesque scene involving floating dust motes and shimmering sun rays streaming through cathedral windows (and Mussida definitely seems to be straining towards the divine at times). The album actually derives most of its inspiration from Italian Renaissance paintings, however, which led to something of major creative breakthrough in how Mussida thought about composition. There are also some ideas lurking within Rueben about alternate tunings, how sound interacts with space, and how music can trigger memories. Russian theologian/physicist Pavel Florensky even gets name-checked in the album description in a statement about "reverse time" and how art's capacity for triggering memories is similar to the dream state. While interesting, none of that would normally enhance my appreciation for what is essentially an unusually good drone album crafted from heavily processed cello, electric guitar (Alessandra Novaga), and bass clarinet (Edgardo Barlassina). However, there are a few pieces on Rueben where it legitimately seems like Mussida's deep thinking and non-musical influences have led him to kind of a fascinating place. On the album's second and sixth pieces, for example, it feels like every frequency and oscillation is in complete harmony with the vibrations of the universe or something.  Needless to say, those two pieces are drone heaven for me, but Rueben is generally an enjoyable and immersive album overall too, as Mussida and his collaborators are quite adept at mingling hypnotic thrum with dark clouds of dissonance and an undercurrent of almost "industrial" textures.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I believe this is Di Domenico's first appearance on Die Schachtel, but the Brussels-based pianist/composer has had quite a prolific and fascinating career, racking up collaborations with a wildly varied array of iconic artists ranging from the ubiquitous Jim O'Rourke to free jazz sax titan Akira Sakata to Nigerian drum god Tony Allen. Given that pedigree, it is a bit of a surprise to see him turn up in a series of ambient albums, but the strange and eclectic Downtown Ethnic Music is too much of a freewheeling and hallucinatory experience to fit comfortably in that milieu (or any milieu at all, really). That said, the album is something of a spiritual (but not stylistic) descendant of Jon Hassell's "fourth world" vision, as Di Domenico set out to reimagine "the future of urban music" with a varied and eclectic host of collaborators. While I sincerely doubt the future of urban music will be anything like the kaleidoscopic and boundary-dissolving psychedelia of this album, Di Domenico has certainly managed to conjure up some truly unique and alien-sounding gems in the attempt.

I believe this is Di Domenico's first appearance on Die Schachtel, but the Brussels-based pianist/composer has had quite a prolific and fascinating career, racking up collaborations with a wildly varied array of iconic artists ranging from the ubiquitous Jim O'Rourke to free jazz sax titan Akira Sakata to Nigerian drum god Tony Allen. Given that pedigree, it is a bit of a surprise to see him turn up in a series of ambient albums, but the strange and eclectic Downtown Ethnic Music is too much of a freewheeling and hallucinatory experience to fit comfortably in that milieu (or any milieu at all, really). That said, the album is something of a spiritual (but not stylistic) descendant of Jon Hassell's "fourth world" vision, as Di Domenico set out to reimagine "the future of urban music" with a varied and eclectic host of collaborators. While I sincerely doubt the future of urban music will be anything like the kaleidoscopic and boundary-dissolving psychedelia of this album, Di Domenico has certainly managed to conjure up some truly unique and alien-sounding gems in the attempt.

The opening "Gap-Filling" is a half-great/half-maddeningly teasing introduction to the album’s elusive and chameleonic aesthetic, as it makes me feel like I managed to just catch the final spaced-out minutes of an intense performance by an experimental guitar/free jazz drummer duo. Regrettably, drummer João Lobo never makes a prominent return, but neither does anything else from that opener, as Di Domenico's imagined future cities feel like a surrealist hall of mirrors. For example, the following "Yoghurt to Yoga" resembles a tense nightmare about an exotic ritual in a distant temple, while "SKJ" resembles a tonally unpredictable retro-futurist synth reverie. At other times, the album resembles a haunted and deranged carnival, a stiltedly funky krautrock jam, and a mash-up of old sci-fi film soundtracks. The latter, "Teratology," is definitely the most strikingly bizarre and "outer limits" moment on the album. In fact, it felt even more so once I realized that it was composed and performed (with an actual choir) and NOT merely a collage of samples (not a pure one, anyway). At its peak, "Tetralogy" calls to mind the cacophonous scene one might imagine if The Shining, 2001, and Solaris crashed into a modern dance troupe and a short wave radio enthusiast. Is it good? Possibly. Is it unique? Absolutely. My personal favorite is considerably more conventional, yet eerily beautiful nonetheless: the closing "Soft on Demand," which is basically a mournfully trippy elegy of gloopy classic sci-fi synth tones.  Part of its appeal may be because a relatively unmangled melody feels like a safe harbor in a maelstrom of endlessly shifting moods and juxtapositions, but I liked a lot of the maelstrom too. While not all of the phantasmagoric urban futures conjured within Downtown Ethnic Music quite hit the mark for me, all are certainly imaginative and vividly realized, which makes this is a solid headphone album for those with a taste for the unusual.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The years between Graham Lambkin’s tenure with the legendary Shadow Ring and his more recent improvisational duos mark a distinct period of creative production within the artist's insular career. Living with his family in Poughkeepsie, NY, from 2001 through 2011 Lambkin recorded and self-released four solo albums that valorized mundane domestic situations while reveling in the liminal spaces between the acts of listening, recording, and producing. Created through an ingenious economy of means, these solo records are as beguilingly seductive as they are uncanny. Perpetually laughing in his own duplicitous face, Lambkin breathed new life into musique concrète and sound poetry, giving outmoded forms a contemporary consciousness while setting the gold standard for a continuously unfolding canon of 21st century tape music.

Poem (For Voice & Tape), Salmon Run, Softly Softly Copy Copy, and Amateur Doubles are now remastered and finally back in print, with Salmon Run and Softly Softly Copy Copy available on vinyl for the first time. This deluxe boxed set of Graham Lambkin's first four solo records includes an expansive 42-page book featuring unseen photos and reproductions of artworks as well as essays and anecdotal recollections providing fresh insight and divulging hermetic secrets by Ed Atkins, Mark Harwood, Matt Krefting, Lawrence Kumpf, Samara Lubelski, and Adrian Rew.

Graham Lambkin (b. 1973, Dover, England) is a multidisciplinary artist who first came to prominence in the early '90s through the formation of his experimental music group The Shadow Ring. As a sound organizer rather than music maker, Lambkin looks at an everyday object and sees an ocean of possibility, continually transforming quotidian atmospheres and the mundane into expressive sound art using tape manipulation techniques, chance operations, and the thick ambience of domestic field recordings. His Kye imprint, founded in 2001, was an instrumental platform for the dissemination of and dialogue between work by an intergenerational cast of artists using sound, including Henning Christiansen, Anton Heyboer, Moniek Darge, and Gabi Losoncy. He began showing his visual art in 2014 with Came To Call Mine, an exhibition curated by Lawrence Kumpf and Justin Luke at Audio Visual Arts in conjunction with the publication of Lambkin’s children’s book (for adults) of the same name, and has since exhibited his work at 356 Mission, Künstlerhaus, PiK, and Blank Forms.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Jeremy Hurewitz's intuitively original, transcendental work as rootless initially crossed our path through cosmic-yet-earthbound instrumental acoustic guitar tapes on two of our favorite labels, Cabin Floor Esoterica and Aural Canyon. Sensing a kinship in sound, we connected online and linked up for a joint rootless & Starbirthed tour across the northeastern US in summer 2019. It was between soundcheck and set on the second day of our tour together that Jeremy recounted to us the fascinating details of the rootless album he worked on before his recent move from Los Angeles to New York.

Recorded April 2019 in the LA studio of sculptor Michael Todd, the two-day session found Jeremy's double-tracked guitar compositions and improvisations meeting the inspired multi-instrumental expression of Mexican musician and folklorist Luís Pérez Ixoneztli. Overseer of a collection of priceless, one-of-a-kind, indigenous instruments from Mesoamerica (many of them pre-Colombian), Luís Pérez’s deep understanding and reverence for these instruments is apparent in his approach to the music. The recording process for each track began with Jeremy's stunningly evocative widescreen fingerstyle acoustic guitar, after which Luís Pérez would listen, consider, and then visit his treasure trove of instruments, returning with several (or many) to contribute to the track. From ocarinas and small whistles that can resemble forest sounds ("peculiar travel suggestions") to dried cocoon shells strung together and used as shakers, to clay flutes that are possibly over a thousand years old ("silence has a sound"), Luís Pérez’s contributions were as spiritual as they were grounded in musical technique. Befitting Jeremy's own experimental, avant-garde approach, some of these contributions moved beyond ancient folk instruments, such as simply pouring water in a tub (on "shared consciousness") or Shamanic breathing ("gorillas in the zoo").

Naturally, upon hearing Jeremy's account of the session we couldn't wait to hear the results. Still, pressing play on the private stream a few weeks later, we could hardly believe the songs and sounds that emerged - existing in form far beyond what our imaginations could conjure. Jeremy's instrumentals create entire worlds, lucid visualizations and emotions colored in perfect detail by the singular presence of Luís Pérez Ixoneztli. Here, rootless has produced an album in perfect harmony with the spiritual and sonic blueprint that Flower Room has articulated across 18+ releases, and this represents a monumental moment for an imprint created solely as a private press label for our own in-house work. For the first time, we welcome a new voice, vision, and source of expression to the Flower Room family, and are proud and ecstatic to present the wholly original melding music of this most high collaboration: rootless' vinyl debut, docile cobras.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

For their fourth album, Merope is joined by the 24 voices of Vilnius chamber choir Jauna muzika and conductor Vaclovas Augustinas.

Interpreting old Lithuanian folk songs and weaving them into their own sonic islands.

More information can be found here and here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest release from Students of Decay’s eclectic sister label comes from prolific and chameleonic Berlin-based producer Naema. On this solo release as Exael, Naema takes the project in an almost single-mindedly rhythm-driven direction that I would roughly categorize as stripped-down or deconstructed techno, but most of the beats are far too idiosyncratic and viscerally pummeling for that to feel quite right. There are also a handful of warmer, more ambient-adjacent pieces that are more in line with what I would expect from someone in the oft-compelling West Mineral Ltd./Experiences Ltd. milieu, as well as a dreamy closing piece that feels almost like hypnagogic pop. While the leftfield surprise of that last piece ("Reality’s Sweetheart") is the most immediately gratifying and memorable moment, the entire album is quite good and masterfully crafted, as Naema is impressively skilled at unleashing skittering and clattering futuristic beats so vibrant and textured that no further accompaniment is needed.

As far as I know, Flowered Knife Shadows is not a concept album, but it nevertheless has an arc that would be completely appropriate for some kind of mechanized sci-fi dystopia narrative. That is not to say that it is dark, but it definitely starts off with jackhammering and precision-engineered percussion assaults that feel like they were created by a cyborg with a real knack for forward-thinking dance music. Then, as the album progresses, the songs start to gradually warm as hints of melody and hissing, crackling ambient textures subtly creep into the mix. In theory, it seems like the latter half of the album would appeal to me more, but early pieces like "Quikgel" and "Boneheaded" are explosive and relentless enough to win me over instantly ("Quikgel" in particular sounds like it was composed by a robot woodpecker with an amphetamine problem). Normally, beats that can be described as "manic" or "hypercaffeinated" tend to grate on me, but Naema is uniquely skilled at quickly and seamlessly evolving from "convulsive" or "obsessively looping" to "sophisticated polyrhythmic onslaught" within the span of a four-minute song. Of course, the more melodic pieces near the end of album are quite good as well, particularly the half-skittering/half-sublime "Anc," the hissing ambient dub of "Rotor," and the lushly melodic, blissed-out finale of "Reality’s Sweetheart" (which sounds like a hypnosis tape transformed into swooningly beautiful futuristic pop). Soda Gong is generally not the first label I turn to when I want to hear a total banger, but Flowered Knife Shadows is exactly that (except when it is something else that is similarly great).

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

In an unexpected flip for their second record, the duo of Eric Hardiman (Rambutan, Century Plants, Burnt Hills) and Michael Kiefer (More Klementines) improvised live. With the self-titled debut being the result of asynchronous file sharing and collaboration, First Encounters was exactly that: the first time the two had actually met in person in any context. That’s anything but apparent from the sound though, as the duo play off of each other perfectly, making for a free form trip through psychedelic spaces with the verve of long time collaborators, even though that is not the case.

In an unexpected flip for their second record, the duo of Eric Hardiman (Rambutan, Century Plants, Burnt Hills) and Michael Kiefer (More Klementines) improvised live. With the self-titled debut being the result of asynchronous file sharing and collaboration, First Encounters was exactly that: the first time the two had actually met in person in any context. That’s anything but apparent from the sound though, as the duo play off of each other perfectly, making for a free form trip through psychedelic spaces with the verve of long time collaborators, even though that is not the case.

Twin Lakes Records/Feeding Tube

Lengthy opener "Evidence of New Gravitation" is immediately indicative of the album: rich guitar, nuanced drumming, and an overall complex sound considering it is only two instruments in play. The sound is clearly loose and free flowing, but it is also deliberate, as if the duo know exactly what they are planning to do next while simultaneously playing off of each other. There is an excellent sense of propulsion via Kiefer's punchy drums and Hardiman's noisy pre-grunge 80s noise rock guitar, with wildly varying dynamics. The same feel runs throughout "Radiant Drifter," where shimmering, chiming guitar is cast out over low rumbling drums that swell up to some excellent freak-outs, which then calm down again. The other two songs on First Encounters feature the duo in a more understated synergy. The less structured "Fitful Embers" is all far away rattling percussion and erratic guitar drills, never coalescing into a solidified rock piece, but never coming off as directionless, either. Lengthy album closer "Of a Similar Mind" is a slower burn, evolving from open spaces, subtle melodies, and sparse cymbals. The growth is slow, but eventually erupts into rapid fire drumming, loud wah-heavy guitar outbursts, and a brilliant heavy psychedelic sensibility.

It is hard to not appreciate the backwards way that Michael Kiefer and Eric Hardiman have approached Spiral Wave Nomads. Waiting until the second record to actually meet in person is certainly not a strategy most artists would attempt, but they manage it perfectly here. Given how different its inception was from the first album, First Encounters has a rawer feel, but there is still a strong sense of consistency, and it is certainly the work of the same duo. With two LPs that complement each other so well, I am curious what collaborative approach a third will bring.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Eve McGivern

- Albums and Singles

The first few seconds hearing Camila de Laborde's child-like, playful vocals may suggest an airy Scandinavian pop direction for duo Camila Fuchs. Assumptions are quickly shattered as the start of Kids Talk Sun gives way to world-weariness. Ghostly vocals stand against a spectral kaleidoscope of tempered electronics, crafted partly by Pete Kember, aka Sonic Boom (Spacemen 3, Spectrum and E.A.R.). Kember lends his finish to hazy and spacey melodies punctuated by luminous pop moments, resulting in an ornate tapestry of emotion woven with reverberation and electronics, sewn together by de Laborde's expressive voice.

Portugal-based Camila Fuchs consists of vocalist Camila de Laborde and Daniel Hermann-Collini. The album is a reflection on the interactions between humans -- particularly children -- and nature. Case in point, de Laborde laments, "There was no way, no need to be careful" in "Moon Mountain," suggesting a hearkening back to a time of fearlessness and innocence. The album itself was recorded near the sea and wilderness around Lisbon; the band's transition between nature and the studio encouraged mimicry of their environment through sonic experimentation. Listen closely to the ascending vocals in "Pool of Wax," supported by a steady and comforting rhythm, before being swallowed in a tide of reverberation. In instrumental "Gloss Trick," one of my personal favorites, there can be heard the biomimicry of seabirds, ship horns -- wait, is that a whale call, or some nighttime creature? Ultimately it really doesn't matter. The point is to "dial up the magic" and reconnect with yourself and your surroundings, summed up nicely in "Roses:"

Dial up the magic, dial the magic up anytime you want

Allow yourself to be the bell tower

Make some noise, feel the noise

On your body, on your nose

Connecting you to the earth

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

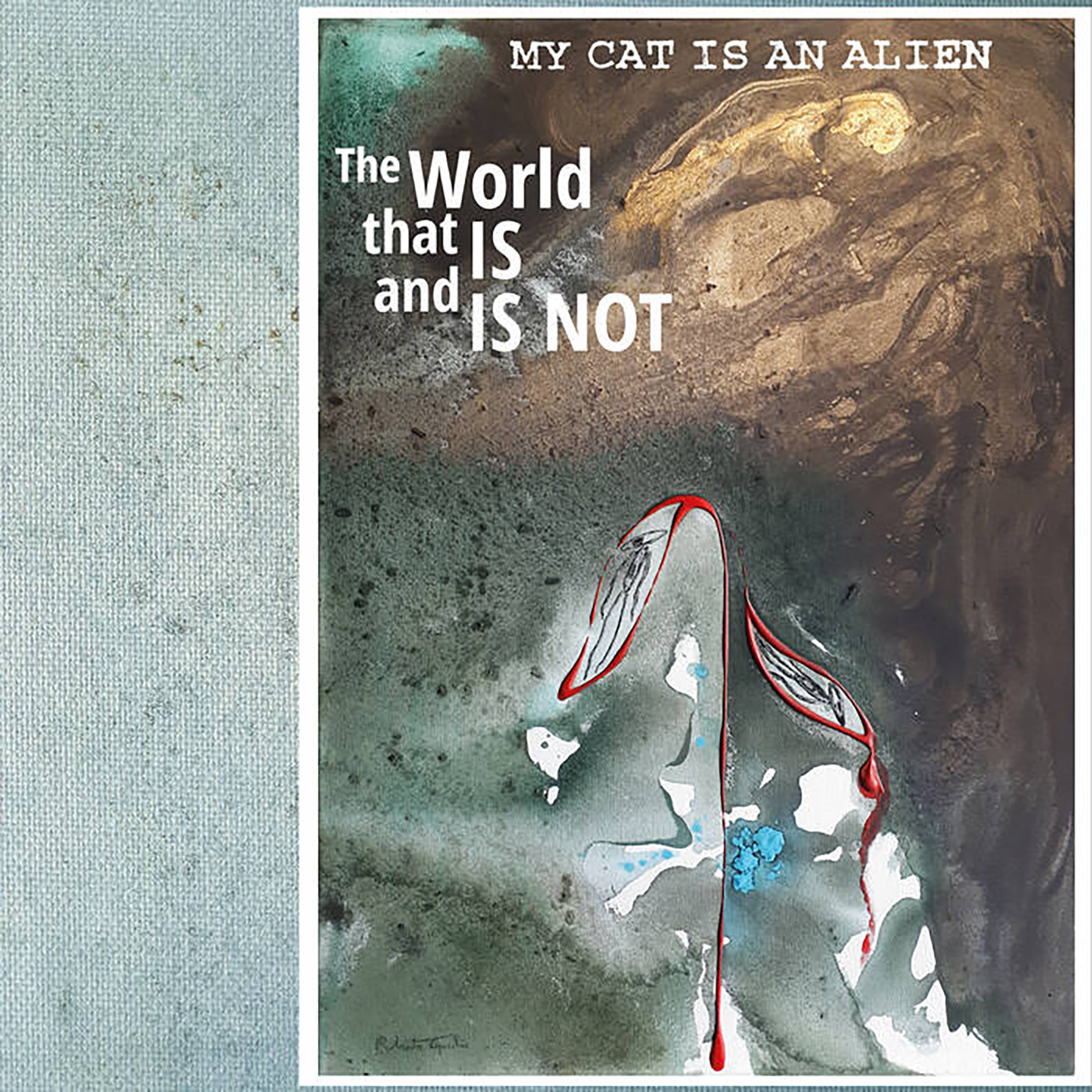

The Opalio Brothers somehow managed to release three strong albums last year, but I believe only this one was (spontaneously) composed and recorded during the pandemic. It was also inspired by it, as The World That IS and IS NOT is billed as a concept album of sorts: an "existential reflection" on a scenario "where everything seems to vanish into the void." That admittedly sounds like a recipe for a bleak album, but the Opalios arguably went the opposite route, heading in a warmer direction to illustrate how music and art can help us transcend the "spiritual disquiet and moral despair" of the current age. To new or casual fans, that increased warmth will probably be nearly imperceptible, as it will be largely eclipsed by the fundamentally outré and mind-meltingly psychedelic elements of this project. Longtime fans will definitely notice a difference though, as this is an unusually meditative album with a satisfying and purposeful arc. While I tend to enjoy the comparative unpredictability of MCIAA's collaborations the most these days, this one captures Roberto and Maurizio in especially inspired form on their own, as I would be hard-pressed to think of a more perfectly distilled example of their warped and wonderful vision.

The Opalio Brothers somehow managed to release three strong albums last year, but I believe only this one was (spontaneously) composed and recorded during the pandemic. It was also inspired by it, as The World That IS and IS NOT is billed as a concept album of sorts: an "existential reflection" on a scenario "where everything seems to vanish into the void." That admittedly sounds like a recipe for a bleak album, but the Opalios arguably went the opposite route, heading in a warmer direction to illustrate how music and art can help us transcend the "spiritual disquiet and moral despair" of the current age. To new or casual fans, that increased warmth will probably be nearly imperceptible, as it will be largely eclipsed by the fundamentally outré and mind-meltingly psychedelic elements of this project. Longtime fans will definitely notice a difference though, as this is an unusually meditative album with a satisfying and purposeful arc. While I tend to enjoy the comparative unpredictability of MCIAA's collaborations the most these days, this one captures Roberto and Maurizio in especially inspired form on their own, as I would be hard-pressed to think of a more perfectly distilled example of their warped and wonderful vision.

This three-song suite deceptively opens with an extended piece that explores somewhat familiar alien terrain, as rattling, discordant, and broken arpeggios from Maurizio's self-made double-bodied string instrument erratically tumble through the dreamlike haze of Roberto's wordless vocalizations. The execution is unusually wonderful, however, as the increasingly sliding, scraping, and bleary strings create a deepening sense of immersive otherworldliness. That sets the stage nicely for the album’s centerpiece, "Whispers of Hope and Illusions," which calls to mind a ramshackle, post-apocalyptic structure of rusted metal wires being violently shaken by a passing storm of extradimensional psychedelia. It is probably one of my favorite MCIAA pieces to date, casting an immersive spell of rattling, undulating, and semi-curdled heaven. Granted, it is still a surreal mindfuck beyond earthbound tonality, but it is complex, nuanced, and weirdly beautiful enough not to feel like a lysergic nightmare (though the storm does get kind of intense). The album closes with yet another unusual (if brief) piece entitled "Prayer For A New Aurora," which feels like a window into a ritual or religious ceremony from an alien planet or alternate dimension. I especially liked whatever sounds like a homemade synthesizer dissonantly attempting to replicate a vuvuzela being strangled. Together, the three pieces flow into quite an absorbing and memorable whole and not a single theme ever overstays its welcome. While I sometimes pine for the days of incredibly long MCIAA albums, I am similarly enamored with beautifully focused and concise statements like this one. If there is another album by the Opalios that strikes a better balance between bold outsider vision and repeat listenability, I certainly cannot think of it.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I believe I have been listening to Biosphere for at least 20 years now, but the project's evolution over the last five years or so has been especially fascinating, as Geir Jenssen's creative restlessness has led him to release one surprise after another. To my ears, 2016's Departed Glories remains the high water mark of this adventurous phase, but I am delighted that Jenssen seems to be actively looking for new challenges and that the results are almost invariably enjoyable and distinctive. This latest release continues that trajectory of endlessly breaking new ground, as the bulk of Angel's Flight was composed for a Norwegian dance production entitled Uncoordinated Dog. More significantly, all twelve pieces were crafted from repurposed fragments of Beethoven's "String Quartet No. 14." Unsurprisingly, much of the album would be unrecognizable to Beethoven, as Jenssen does an admirable job of blurring, stretching, blackening, and chopping his source material into a compellingly hallucinatory neo-classical fever dream.

I believe I have been listening to Biosphere for at least 20 years now, but the project's evolution over the last five years or so has been especially fascinating, as Geir Jenssen's creative restlessness has led him to release one surprise after another. To my ears, 2016's Departed Glories remains the high water mark of this adventurous phase, but I am delighted that Jenssen seems to be actively looking for new challenges and that the results are almost invariably enjoyable and distinctive. This latest release continues that trajectory of endlessly breaking new ground, as the bulk of Angel's Flight was composed for a Norwegian dance production entitled Uncoordinated Dog. More significantly, all twelve pieces were crafted from repurposed fragments of Beethoven's "String Quartet No. 14." Unsurprisingly, much of the album would be unrecognizable to Beethoven, as Jenssen does an admirable job of blurring, stretching, blackening, and chopping his source material into a compellingly hallucinatory neo-classical fever dream.

The album instantly descends into darkly phantasmagoric territory with "The Sudden Rush," which conjures a sinister-sounding impressionist swirl of blurred and uneasily harmonizing orchestral fragments. To some degree, that is the tone for the entire album: a series of variations upon the theme of smeared and slowed strings bleeding together and queasily undulating. Both the mood and structure of the individual pieces can vary quite a bit, however. Most of my favorite moments fall in the middle of the album, like the oscillating, slow-motion chord progression of "As Weird as the Elfin Lights" or the dreamlike flutes and viscerally throbbing pulse of the title piece. That said, the album probably reaches its zenith with the stuttering and gnarled closer "The Clock and Dial," which calls to mind several orchestral loops being played at once through a blown-out bass amp. Jenssen treats the hapless Beethoven similarly violently in the heaving "Unclouded Splendor," which achieves an almost operatic intensity from erratically timed and overlapping slashes of strings. There are a number of other fine pieces throughout the album as well, many which call to mind a reincarnated Debussy with a penchant for loops, a newfound love of dissonance and tension, and access to contemporary production software. Or maybe they simply resemble Beethoven as re-envisioned by The Caretaker, albeit considerably more vivid and robust than that sounds. Angel's Flight is not a stroll through the ruins of a haunted and moldering memory ballroom so much as a lush, enveloping, and oft-poignant symphony in which the fabric of reality frays and bulges as time ceases to be predictably linear. Needless to say, that is quite an appealingly disorienting and immersive illusion to linger in. I certainly did not expect Biosphere to ever sound like this, but I am delighted that Jenssen's muse led him to such wonderfully unfamiliar territory.

Samples can be found here.

Read More