- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

It is difficult to acknowledge S U R V I V E’s new album without touching on the hype surrounding it. Half of the Austin band, Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein, are responsible for the soundtrack to Stranger Things, which has received significant attention. But the fact of the matter is that the band (also featuring Adam Jones of Troller and Mark Donica) has been composing synth heavy film score work for years now, and while they are completely deserving of the attention their work is now receiving, RR7349 would be just as amazing of a record without the hype surrounding their extracurricular activities.

It is difficult to acknowledge S U R V I V E’s new album without touching on the hype surrounding it. Half of the Austin band, Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein, are responsible for the soundtrack to Stranger Things, which has received significant attention. But the fact of the matter is that the band (also featuring Adam Jones of Troller and Mark Donica) has been composing synth heavy film score work for years now, and while they are completely deserving of the attention their work is now receiving, RR7349 would be just as amazing of a record without the hype surrounding their extracurricular activities.

Since 2010 the quartet has been working on their analog synth soundscapes, albums that weave these vintage sounds into bleak and at time frightening moods.Of course, parallels with John Carpenter’s soundtrack work are inevitable, and while I have no doubt he is an influence, their work is distinctly their own.While they are intentionally using vintage gear, the production technique is distinctly contemporary.Rather than trying to copy a sound from 30 years ago, they use that to create something fresh and modern.

Alongside the production, much also has to be said for the songwriting and composition.Unlike entire genres that have been built upon a foundation of replicating 1980s neon aesthetics and damaged VHS tape visuals, composition is the focus, rather than repetitive hardware demos.This is immediately evident on album opener "A.H.B."What begins as a simple drum machine and bassline structure, propelled by an intentionally simplistic synth lead, soon becomes a constantly evolving and developing work, shifting layers and patterns rapidly but never losing consistency.There are definite film score similarities to be heard here, but the work itself is too dynamic to be just a background piece.

While there is a lot of variation between songs on RR7349, the mood stays a consistent dark and sinister one.The slow shuffle of "Dirt" is all big crashing drum machine and pulsating synth arpeggios, with complex melodies weaved throughout that become the focus by the end."High Rise" features not only a great bit of drum machine programming, but also a diverse bass sequencer driving it to a sound that could almost be vintage Front 242 at their most atmospheric.

The album is not all percolating keyboards and crunching drum machine, however.The surging synth strings of "Other" cut through an intentionally uncomfortable amount of space, resulting in an atmospheric, slightly menacing piece of unsettling music."Low Fog" is a perfectly titled piece, with its opaque miasma of buzzing electronics and beat-less soundscape.The mood is uncomfortable and gives the sense that something horrible is about to happen at any time, made all the more intense with its extremely slow fade out.

Closing on "Cutthroat," a complex, rhythmic mass of crashing rhythms and big, boisterous leads is also a brilliant stroke, ending the album with an appropriate culminating climax of all the elements that made it so great.S U R V I V E may be current media darlings due to their other work, but RR7349 is a further refinement of the sound honed on their last self-titled full length.It may have the mood in place, but there is simply too much going on for this album to be considered soundtrack music, because it would easily upstage any visual component it may be paired with.It truly is an audio-only cinematic experience, and one that is gripping until the very last moments.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Multimedia artist Steve Roden has stated that his work often begins with the product of some other artist, and becomes a jumping off point for him to create his own inspired work. "Distance Piece," the audio component of Striations presented here, was part of a larger body of work inspired by an unfinished sculpture by his grandmother. The audio portion that makes up this disc may lose a bit in the translation from its overall conceptual framework, but still makes for a strong work on its own.

Multimedia artist Steve Roden has stated that his work often begins with the product of some other artist, and becomes a jumping off point for him to create his own inspired work. "Distance Piece," the audio component of Striations presented here, was part of a larger body of work inspired by an unfinished sculpture by his grandmother. The audio portion that makes up this disc may lose a bit in the translation from its overall conceptual framework, but still makes for a strong work on its own.

"Distance Piece" itself is a 46 minute composition that was made to accompany the six minute film Striations, and played outside of the Sculpture Center in New York, where the film was screened on a loop inside.By design, the audio portion was intentionally divorced from its visual component, but is intrinsically linked at its overall composition, however.The audio is culled from treated field recordings that were collected when Roden and artist Mary Simpson were filming, capturing cars and birds in the distance, speaking, tapping rocks, bowing cymbals, etc.

These recordings were then treated and processed by Roden into expansive rich, resonating tones.There remains a constant low-level hum throughout, so that even when the mix becomes extremely open and superficially sparse, it never transitions fully to silence.The elongated tones and heavy panning effects make it unclear where the sounds were initially sourced from, though the occasional hint of human voice or chirping bird occasionally slips through to stand out.

The entirety of the piece is underscored by a passage of electric guitar, playing a note progression created from a passage of text by sculptor Henry Moore that Roden's grandmother kept around as an inspiration.For the most part this too appears largely in its original form, a cold passage of tonally pure notes that underscore the more abstract passages, weaving through the less obvious sounds surprisingly clearly.

While the piece has its strengths, at times "Distance Piece" simply fades off into the distance.Given that it was originally part of a larger multimedia piece, and intended for incidental listening to viewers walking to, from, and around where the film was being screened, it suffers from being the sole focus of attention.It is never a badly executed work by any means, it just simply becomes stagnant and seemingly unchanging at times, which can be a flaw in this sort of electro-acoustic work.

I hope my criticism of Roden's work does not come across as too harsh, because by no means is Striations a bad piece of music.At times it is simply too subtle for its own good, and by being presented as a single album-length work, my attention tended to wander here and there throughout.Fans of his previous work, and adherents to this minimalist brand of experimental work will easily find much to enjoy here, it just does not manage to transcend far beyond the genre’s adherents.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The enigmatic Fossil Aerosol Mining Project have somehow managed to retain their anonymity in the eight years since the project was reactivated. With this, their consistency in presenting long lost audio recordings (or excellent forgeries of them) in a new and reconstructed context has not waned in the slightest, and this second release this year (the other being digital-only) keeps that mystery alive and fascinating.

The enigmatic Fossil Aerosol Mining Project have somehow managed to retain their anonymity in the eight years since the project was reactivated. With this, their consistency in presenting long lost audio recordings (or excellent forgeries of them) in a new and reconstructed context has not waned in the slightest, and this second release this year (the other being digital-only) keeps that mystery alive and fascinating.

Afterdays Media/Helen Scarsdale Agency

Revisionist History is actually a two-plus hour work, consisting of the full length CD and an additional nine pieces (Revisionist History Volume 2) downloadable with an included code.The material on the physical portion of the release is comprised of new compositions that utilize previous work from the group’s expansive past as a source material, while the downloadable portion is more explicitly based in revisiting and reworking older compositions.

Because of that the CD based material has the more fleshed out and diverse sound to it when comparing the two.The FAMP sound is in full effect, however:layers of decaying audio tape mixed with bizarre studio treatments and processing.In many of these cases though, the band(?) straddles that line between noise and music extremely well.A piece such as "Napthol Impermanence" is an example of this:shimmering sounds and what may be an actual synthesizer underscoring the more dissonant moments well.There are simple melodies also to be heard within the clattering noises and field recordings of "Filtered By Limestone" as well.

At other points on the album what sounds like existing music is used as a source, destroyed and manipulated into oblivion.What best sounds like ancient recordings of strings and music boxes lurk below the surface of "Vestigial Sideband", but seemingly rotting below layers of organic static and warm crackles of decay.A similar sense appears on "Mistranslated Practices", as expansive electronic passages lay beneath crunchy loops and disorientating production, with fragments of radio communication adding to the confusion.On "Squatters at the Launch Facility", FAMP uses the piece’s nearly 16 minute duration well, first blending voices and field recordings with rhythmic loops, building complexity and variation.It has a cyclic structure to it, but the layers pile up atop each other wonderfully to just disintegrate at the conclusion.

The downloadable portion supposedly consists of previous works revisited (of which I have not heard the originals of), but it could just as easily be entirely new material.The sound is consistent with the physical portion, capturing an array of textures, found recordings, and rotting magnetic tape and reshaping them into complex collages that bear little resemblance to how they began.It seems as if the treatments of this older material were more restrained, however, and so the sound lacks a bit of the complexity of the newer material.This would make sense if the group is reworking material dating back to the mid 1980s, however.

Fossil Aerosol Mining Project's sound is one that has been well established in their recent spate of releases, and Revisionist History is another strong entry.The music is murky, weird, and at times uncomfortable, which is exactly what the mysterious group intends I suppose.As it stands, it is a wonderful collage of crackling textures, mutated tones, and a motivation to decode the sounds as much as possible, though I have had little success doing that myself.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

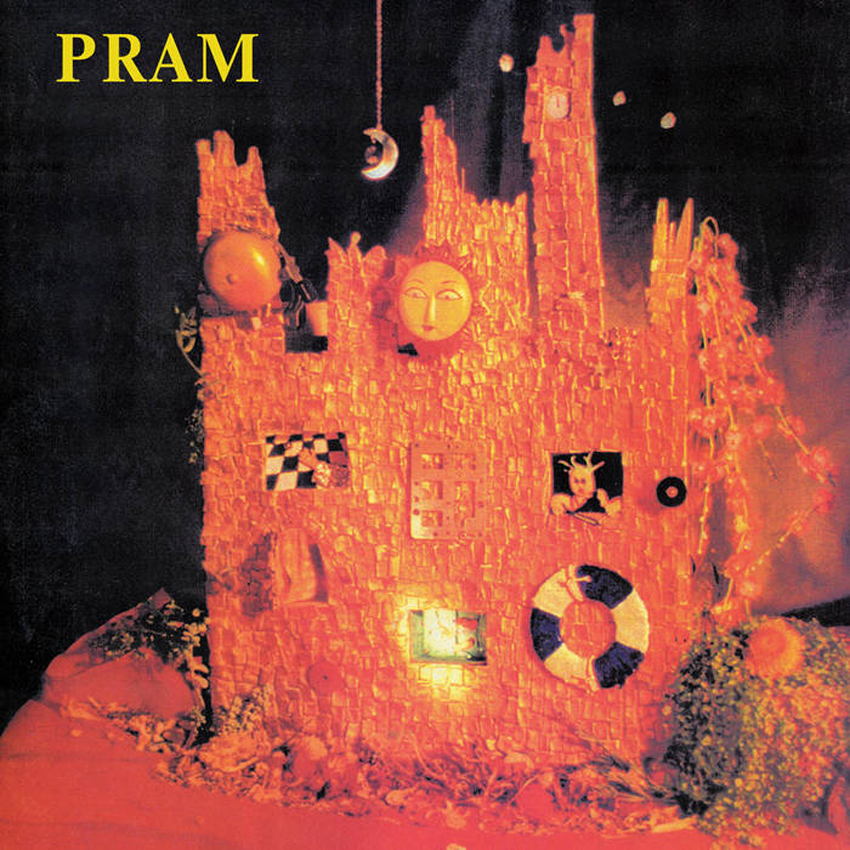

Birmingham’s Pram are the rare band that can cause me to simultaneously think conflicting thoughts like "it is absolutely criminal that this band was never as big as Stereolab" and "it is abundantly clear why this band never quite managed to transcend cult status."  In any case, they were unquestionably one of the more idiosyncratic, inspired, and polarizing bands of the '90s, though they finally managed to achieve some widespread success in the early 2000s.  In fact, Helium was recently hailed by FACT as one of the greatest post-rock albums of all-time, while an article on The Quietus proposed The Stars Are So Big as the best album of the '90s.  Appropriately, those first two Pram albums (originally released on Too Pure) have now gotten well-deserved vinyl reissues from Medical Records.  At the risk of sounding reductionist, both of these albums fall into Pram's Krautrock-influenced phase, preceding their (also reductionist) aesthetic swing into more exotica-influenced territory.  Describing Pram as "Krautrock-influenced" does not even remotely begin to capture how bizarre, artfully deranged, and fun some of these songs are though.

Birmingham’s Pram are the rare band that can cause me to simultaneously think conflicting thoughts like "it is absolutely criminal that this band was never as big as Stereolab" and "it is abundantly clear why this band never quite managed to transcend cult status."  In any case, they were unquestionably one of the more idiosyncratic, inspired, and polarizing bands of the '90s, though they finally managed to achieve some widespread success in the early 2000s.  In fact, Helium was recently hailed by FACT as one of the greatest post-rock albums of all-time, while an article on The Quietus proposed The Stars Are So Big as the best album of the '90s.  Appropriately, those first two Pram albums (originally released on Too Pure) have now gotten well-deserved vinyl reissues from Medical Records.  At the risk of sounding reductionist, both of these albums fall into Pram's Krautrock-influenced phase, preceding their (also reductionist) aesthetic swing into more exotica-influenced territory.  Describing Pram as "Krautrock-influenced" does not even remotely begin to capture how bizarre, artfully deranged, and fun some of these songs are though.

The Stars Are So Big… (1993) was Pram's debut album, released shortly after a pair of earlier EPs (one of which, the self-released Gash, was engineered by hometown compatriot Justin Broadrick).  While it is convenient and somewhat accurate to lump the band’s sound at this time together with Stereolab, the presence of vocalist Rosie Cuckston ensured that Pram were very much a singular identity.  Cuckston is a bit of a double-edged sword though, as she is revered by fans and absolutely integral to Pram's fundamental otherness, but she is a bit of an acquired taste for the unconverted.  While her vocals are generally described as "childlike," it actually feels more like the band just invited their terminally shy friend up on stage to sing for the first time...or maybe she just sounds like someone in a trance.  It is hard to say which is more accurate, but her vocal style is definitely very much all her own.

In some respects, that is a bit problematic, as Rosie's distracted-sounding, quavering, and not entirely on-key vocals necessarily become the primary focus of every song, regardless of how interesting and inventive the underlying music can be.  In other respects, Cuckston is a crucially eerie, iconoclastic, and defining presence, though the rest of the band is hardly conventional (their original line-up was based solely upon vocals and theremin, for example).  Therein lies the central paradox and complexity of Pram: their most obviously inaccessible feature is also one of the most essential and beloved aspects of their aesthetic.  I am personally still a bit on the fence regarding Cuckston's vocals, but I am gradually coming around, as she is a one-of-a-kind songwriter.  Cuckston aside, the other huge difference between Stereolab and Pram is that they assimilated the same influences in very different ways: Stereolab did it sauvely, while Pram turned out like a messy, precarious, and freewheeling circus.

From a pop music perspective, "Radio Freak in a Storm" is the definite high point of the album, boasting a wonderfully plinking arpeggio hook, a cool keyboard melody, and a pleasantly swaying groove.  Pram clearly were not too worried about trying to write catchy singles though, as the song frequently derails into dissonant interludes of gnarled strings.  Elsewhere, "The Ray" is quite an unusual and noteworthy piece, as the backing music is just a sparse keyboard melody and some howling noise.  As far as I am concerned, however, the real zenith of The Stars Are So Big is unquestionably the gorgeous 16-minute epic "In Dreams You Too Can Fly."  In fact, it may very well be the crown jewel of Pram's entire career.  While Cuckston eventually starts singing near the end, the piece is primarily an instrumental and it captures the band at the absolute height of their powers.  I have absolutely no idea who is playing what instrument, but the roiling guitar maintains a smoldering tension worthy of Sonic Youth and the rhythm section keeps the momentum building wonderfully as an extended and surprisingly great trumpet solo unfolds.  In short, it captures the entire band performing at their absolute best without the distraction of trying to shape themselves into an accessible song-like shape.  It is a truly wonderful piece of music.  The remainder of these eight songs certainly all have their nice touches too, but "In Dreams You Too Can Fly" is the real reason to hear this album. For the most part, Pram got noticeably better with their next release.

On that note, the following "Dancing on a Star" is even better, veering off into quite a bit of spaced-out abstraction while still managing to stay grounded with a wonderfully rolling and stumbling groove.  In fact, I can think of few other bands that ever managed to get quite as crazy and outré as Pram do here while still managing to loosely adhere to something resembling conventional song-like structures.  "Nightwatch" is even more bonkers, as it sounds like there is simultaneously someone banging on kitchen utensils; a very serious violinist trying to hold the song together; a wobbly, weirdly bass-heavy theremin; a lazily melodic one-finger keyboard melody; and a gnarled eruption of guitar feedback all happening at once.  The overall effect is like looking into a snow globe that portrays a spirited talent show in a psych ward.  I think that statement effectively summarizes early Pram in general, actually: I cannot stress enough how improbably far out Pram managed to go while still masquerading as a pop/rock band.  I doubt it was completely intentional, but the contrast between Cuckston's vocals and the band's music was a stroke of genius.  Having a seemingly guileless and starry-eyed poet as a front person is the perfect distracting cover for a band endlessly hellbent on conjuring up such a perverse, everything-but-the-kitchen-sink cacophony.

As bizarre as things gets, it is generally the rhythm section that makes Helium work so well, as even the slightest content is bolstered by an unrelenting momentum.  Cuckston’s lyrics aside, there is not much at all to "Things Left on the Pavement" other than a solid bass line and some very spirited drumming.  Nevertheless, that proves to be more than enough to carry the song (though it helps that it eventually erupts into a wild interlude of yelping, jungle-like noises).  Though the band can sound quite mannered on record at times, it is easy to see how such unpredictable frenzies of chaos made Pram a somewhat legendary live act.  Interestingly, however, it is one of the more straightforward and Cuckston-centric pieces that steals the show: the lilting and melancholy "My Father the Clown."  While there is predictably a complete collapse into abstract lunacy near the end, the appeal is solely that it is absolutely perfect song with an absolutely perfect melody.

Sadly, "Clown" does not sustain its greatness for its entire duration due to Pram's genius for self-sabotage, but it still hits the highest highs of anything on the album.  That is quite an achievement, as Helium is positively riddled with fine moments.  While the depth and poignancy of "Clown" is a bit of an aberration, it is pieces like the rollicking "Blue" and "Dancing on a Star" that most effectively embody Helium's spirit, which is one of infectiously unhinged fun and cheerfully wonky experimentation.  Recognizing Helium as a crucial post-rock album is great, but that fails to convey how truly bizarre and uncategorizable it actually is.  "Post-rock" is only a vaguely plausible label here because there is not currently a "weird, carnival-esque, and introverted party album" genre.  In a perfect world, Helium would have birthed it, but it would have been a damn hard act for anyone else to follow.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

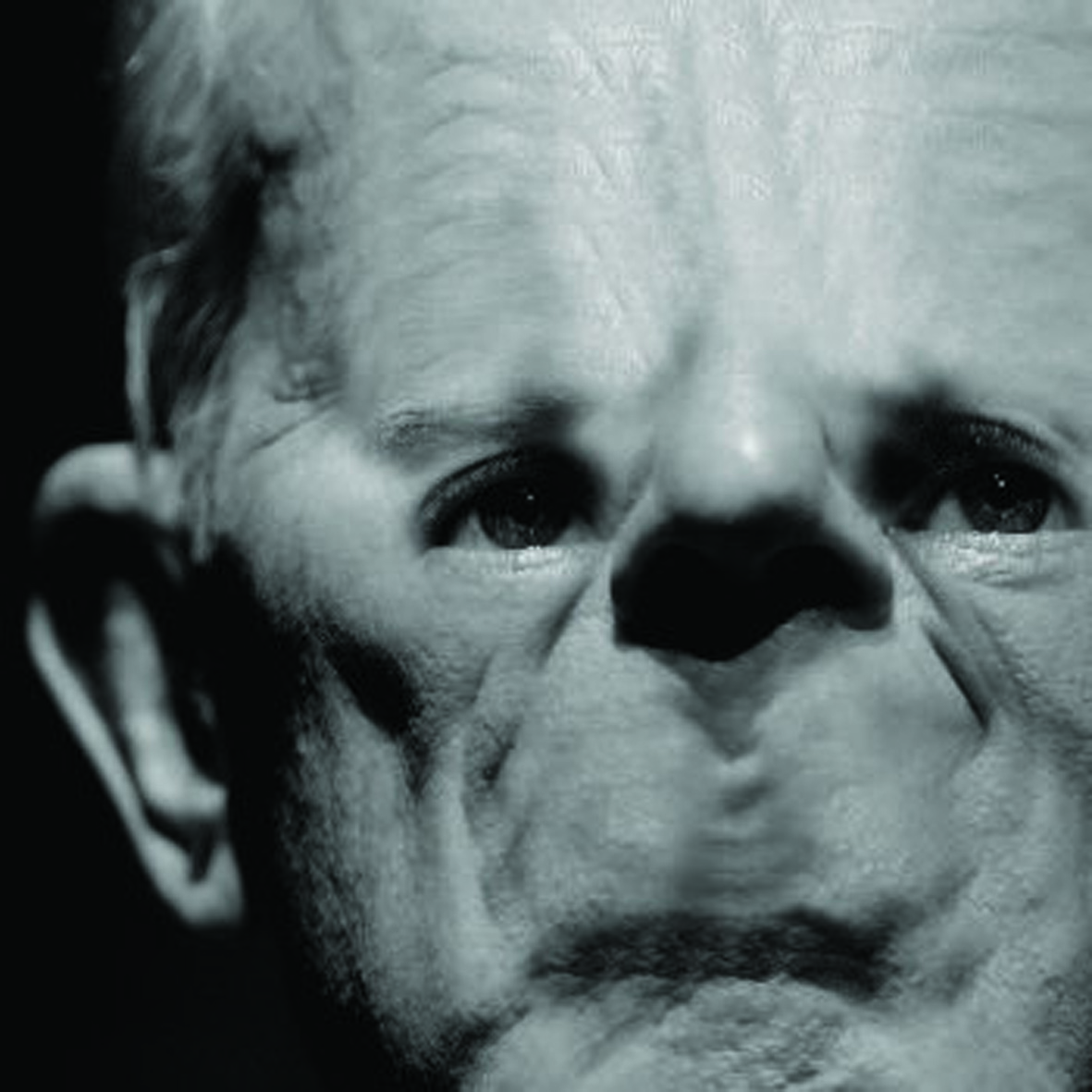

I cannot pretend to keep up with Andrew Liles' overwhelmingly voluminous solo output, but I pounced on this album, as it seemed significant that the generally dormant United Dairies label had reawakened to bestow its imprimatur upon this opus.  Happily, my instincts proved to be unerring (as usual).  United Dairies is the perfect home for an album as aberrant as this one: while Steven Stapleton has described it as "a masterpiece of modern contemporary composition" and Liles ostensibly drew his inspiration from the '50s and '60s avant-garde, The Power Elite more accurately sounds like a prolonged nightmare taking place inside the rusted machinery of a clock tower.  This is easily one of the year's strangest and most adventurous albums.

I cannot pretend to keep up with Andrew Liles' overwhelmingly voluminous solo output, but I pounced on this album, as it seemed significant that the generally dormant United Dairies label had reawakened to bestow its imprimatur upon this opus.  Happily, my instincts proved to be unerring (as usual).  United Dairies is the perfect home for an album as aberrant as this one: while Steven Stapleton has described it as "a masterpiece of modern contemporary composition" and Liles ostensibly drew his inspiration from the '50s and '60s avant-garde, The Power Elite more accurately sounds like a prolonged nightmare taking place inside the rusted machinery of a clock tower.  This is easily one of the year's strangest and most adventurous albums.

Although its musical inspirations look reverently backwards, the conceptual inspirations behind The Power Elite are grimly contemporary, abstractly conveying "the impotence of the masses living in the shadow of military, economic and political institutions."  Much like a Merzbow album, however, that conceptual inspiration does not manifest itself all that obviously in the actual music (other than making it clear that this album is dark for a reason).  Still, it is nice to know that NWW are united in their opinions on the state of the world (Dark Fat was dedicated to "psychopathic scumbag individuals, regimes and corporate filth").  For the most part, The Power Elite just sounds hallucinatory and hellish, though whether it represents the living nightmare of the masses or the imagined Boschian future hell of the damned architects of our current state is anybody's guess (perhaps both?). There is a smattering of earthbound touches like distant church bells throughout the album, but the warped and pitch-shifted voices of "Artificially Induced Consciousness" definitely lie the otherworldly place between "bovine" and "demonic."  Incidentally, "Artificially Induced Consciousness" is one of the most impressive and fully realized pieces on the album, beautifully weaving a queasily dissonant reverie that sounds like an infernal barnyard full of out-of-tune, fitfully operational music boxes.

While a few of the other pieces are distinguished by the aforementioned voices or bells, the overall aesthetic of The Power Elite seems to be one of overlapping plinking and pointillist strings and discordant strums.  It sounds like Liles' arsenal consisted primarily of music boxes and rusty, out-of-tune harps, but he could have been plucking at the guts of a heavily modified piano as well.  In any case, the overall effect is quite a disorienting one of rippling, layered dissonance occasionally embellished by unintelligible voices or distantly chiming bells.  The only real classical avant-garde reference point that I can think of is Morton Feldman, as all of the pieces here bleed together to create a sustained and simmering uneasiness.  Unexpectedly, however, there are few departures from that aesthetic near the end of the album.  The first is "Affluenza," which seems to employ bowed strings to achieve something almost melodic, though the primary emphasis is still upon texture and harmonic overtones.  Much more dramatic is the following "The Iron Law of the Oligarchy," which collages layers of sampled operatic sopranos with a dissonant piano performance and something that sounds like someone having a laser battle in a pigpen while strangling a balloon animal.  It is probably safe to say that I will not use that description for any other albums this year.  Near the beginning of the album, "Horatio Alger Myth" is also a bit of curveball, converging into a sickly assemblage of woodwinds and brass for a very wrong-sounding fanfare.

If The Power Elite has any real shortcoming, it is merely that only "The Iron Law of Oligarchy" strongly stands out as an individual piece.  In the wrong light, it might seem like Liles is endlessly recycling the same ideas for the majority of the album, but it seems like a conscious and sound aesthetic decision from where I am sitting.  If the album lacks in distinct peaks, it more than makes up for it with its masterfully sustained mood and seamlessly flowing arc.  Also, for a symphony of utter wrongness, The Power Elite is surprisingly listenable, as it never feels particularly jarring or heavy-handed at all.  While it is definitely uneasy listening in the extreme, I cannot say that I have ever heard anything else quite like it, which makes it a bit of a minor masterpiece and very likely to be the strongest release to come from the NWW camp this year.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Stephen Morris and Gillian Gilbert’s unabashedly poppy New Order side project has remained a largely forgotten one, aside from perhaps the small splash created by their debut single in 1990. While there are certainly some artistic reasons for O2’s marginalization, the duo’s most significant problems were bad luck, bad timing, and the chaos surrounding the collapse of Factory Records. Thankfully, LTM has now reissued both of their albums, giving them a long-deserved second chance to find some appreciative ears.

Stephen Morris and Gillian Gilbert’s unabashedly poppy New Order side project has remained a largely forgotten one, aside from perhaps the small splash created by their debut single in 1990. While there are certainly some artistic reasons for O2’s marginalization, the duo’s most significant problems were bad luck, bad timing, and the chaos surrounding the collapse of Factory Records. Thankfully, LTM has now reissued both of their albums, giving them a long-deserved second chance to find some appreciative ears.

Superhighways is The Other Two’s second (and final?) album and was originally released in 1999, nearly a decade after its predecessor. Stephen and Gillian are joined by vocalist Melanie Williams for several tracks, whom UK readers may remember as the voice of a big dance hit by Manchester’s Sub Sub. In fact, the album begins with one of the William’s songs (“You Can Fly”), a piece that I found extremely jarring and kind of awful. The problem is not that Melanie is not a capable vocalist (quite the opposite, actually), but her powerful soul diva vocals are about as far from Bernard Sumner's understated deadpan as it is possible to get. For that reason (and some others), her three contributions do not sound at all like the work of New Order members. That is perfectly fine, of course, but there is a much larger problem evidenced as well, the one that is most responsible for O2’s obscurity. Many songs on this album are unapologetically slick, mainstream, and deliberately targeted for the charts, yet they were conspicuously and hopelessly detached from all prevailing musical trends at the time of their release. The first several songs of the album sound like they could have been smash hits in the late ‘80s or very early ‘90s, but O2 seem to have been blissfully indifferent to the enormous changes that had occurred in the electronic/dance music landscape during their lengthy hiatus.

However, despite their clear temporal dislocation from the electro zeitgeist, Stephen and Gillian could not disguise the fact that they still knew how to write catchy, well-produced pop gems. The first evidence of this comes with the third song, “The River,” where Gillian takes over the lead vocals. While still undeniably frothy and over-polished, Gilbert’s understated vocals are much more to my liking. Also, there is an excellent string hook and a very strong chorus. It turns out not to be fluke, as the remainder of the album grows steadily more interesting, likable, and contemporarily relevant (I especially enjoyed the melancholy, burbling “Cold Feet” and the incredibly infectious chorus of “Hello”). The duo definitely front-loaded Super Highways with “the hits,” which ironically turn out to be the least rewarding songs on the album (some even regrettably approximating a dancier Wilson Phillips). Two of the weaker tracks, however, are reprised at the end of the album in remix form as bonus tracks. Andy Votel does an excellent job turning “Super Highways” into a better song, but “You Can Fly” is still pretty dreadful (though now presented as a thumping club jam). Also included is a hard-to-find remix of the band’s sole hit (1990’s “Tasty Fish”).

I had always thought of Peter Hook as the guiding force that made New Order a great band, but I have since reevaluated my opinion somewhat. Once it gets going, Superhighways is packed full of catchy beats, inspired arrangements, tight structures, and great melodies that would have made for a great New Order album had Bernard Sumner handled the vocals (and the lyrics, which can get pretty vacuous at times). In fact, there are even some moments (like the treated classical vocal snippet in “Weird Woman”) that arguably surpass Stephen and Gillian’s day job. Even sans Sumner, Superhighways could have been a pop hit, had it been released at the right time and with proper promotion. I would definitely be embarrassed to own an album like this if it didn’t have any Factory Records associations, but at its best it is a fun and catchy guilty pleasure. I will probably only listen to this secretly, but I will listen to it.

Samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Dutch sound artist and Machinefabriek collaborator Wouter van Veldhoven has maintained quite a low profile since he began releasing music in 2005, quietly assembling a unique body of work with a minimum of fanfare or self-promotion. Fortunately, someone at Mort Aux Vaches noticed anyway and invited Wouter to drop by the studio with his arsenal of decrepit reel-to-reel tape players and home-built equipment for a live session of wobbly, understated ambient beauty.

Dutch sound artist and Machinefabriek collaborator Wouter van Veldhoven has maintained quite a low profile since he began releasing music in 2005, quietly assembling a unique body of work with a minimum of fanfare or self-promotion. Fortunately, someone at Mort Aux Vaches noticed anyway and invited Wouter to drop by the studio with his arsenal of decrepit reel-to-reel tape players and home-built equipment for a live session of wobbly, understated ambient beauty.

The 35-minute set consists of three pieces, all of which are untitled. The opening work is a fragile, hazy edifice built from what sounds like several decayed tape loops of a melodica (or perhaps an accordion). It is relatively sparse and one-dimensional, but manages to work anyway, simply because it is so sad and tremulous. The central elements of Wouter’s aesthetic seem to be spaciousness, simplicity, and deliberate frailty. Rather than layering his loops to create density and complicated interactions and harmonies, he instead allows his work to unfold teasingly slowly and woozily, as if there is a good chance that the entire thing may collapse at any second or that the next note might never come.

The second track, while significantly longer, does not tamper much with van Veldhoven’s formula. However, the mood takes a more ominous turn, as somber chords insistently swell up from the crack and hiss of the tape while quivering higher pitches form a disquieting impressionist fog above it all. Soon a strange delayed rustling begins to flap through the murky sonic landscape at predictable intervals like a giant mechanical bird, and a host of non-musical flutters and throbs begins to intensify before it all fades slowly away.

The epic (nearly 20-minute) closer that follows it is the most engrossing and emotionally affecting distillation of van Veldhoven’s vision on the album. Again, however, there is no real dramatic change in what he does. Instead, Wouter merely allows himself more time to weave his teetering, quavering sound web. The instrumentation changes a bit though—I definitely hear a guitar and a xylophone this time around. They are not played at all conventionally, however, but are merely sound sources for a drifting and diffuse cloud of blurred notes. About halfway through, the now deceptively complex fog becomes bolstered by shimmering cymbals and the looped melancholy sighing of a human voice. The voice soon begins to overlap itself and unexpectedly coheres into a hypnotic, immersive, and heavenly mantra that sounds as divinely inspired as any Gregorian chant.

Mort Aux Vaches has captured an impressive and inspired performance. This is not necessarily a great or essential stand-alone work due to its brevity and sketch-like nature (brilliant closing piece aside), but it does have the important distinction of being my first exposure to van Veldhoven and it was an extremely favorable one. I am very eager to hear what Wouter can do when he has no time and equipment constraints limiting him: it seems like he has no trouble at all assembling the base elements for works of sublime beauty, but merely needs a sufficient amount of time to bring them to full flower.

Samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Our Love Will Destroy The World's debut full-length (2009's Stillborn Plague Angels) was a strikingly ugly, cathartic, and demonic affair that seemed to take guitar-based noise to its logical extreme. It turns out that it hadn't, as Campbell Kneale's newest black-hearted slab of vinyl makes it clear that he has no trouble at all dreaming up ingenius new ways to be bilious and face-meltingly heavy.

Our Love Will Destroy The World's debut full-length (2009's Stillborn Plague Angels) was a strikingly ugly, cathartic, and demonic affair that seemed to take guitar-based noise to its logical extreme. It turns out that it hadn't, as Campbell Kneale's newest black-hearted slab of vinyl makes it clear that he has no trouble at all dreaming up ingenius new ways to be bilious and face-meltingly heavy.

“Halloweenteeth” commences the horror of Fucking Dracula Teeth with a relatively tame low drone that is soon joined by a ride-cymbal drumbeat and a repeating feedback loop. Within a minute or so, however, all hell breaks loose and the groove is blindsided by an avalanche of shrieking, howling white noise chaos. At that point, all pretensions of song-craft and accessibility are conclusively vanquished for the remaining duration of the album. The rest of "Halloweenteeth" unfolds as a dense, throbbing, roiling squall of seething ugliness and it is wonderful. Somewhere beneath it all lurks something melodic and xylophone-like, but it is never allowed to come to the fore. Instead, it sounds like a pleasant song that is being bludgeoned to death.

“The Pleasure's Everlasting” follows in much the same vein, though it is a bit more static and droning than its predecessor. It is built upon a thick bed of hums and crackles, but strangled guitar and swooping gales of static and electronics continually threaten to burst forth from the entropic miasma and take the piece in a harsher direction. It never happens though. In fact, the piece concludes without ever evolving or cohering into something more, yet it never becomes at all boring due to the sheer density and complexity of squirming and seething small-scale eruptions that Campbell has woven into it. While it is the certainly the most minor piece on the album, it is a very effective exercise in the power of simmering tension.

The entire second side of the record is occupied by the album's clear centerpiece, "In Sleep We Creep," which unexpectedly begins with the coupling of sloppy noise rock noodling and a '90s techno synth bass line. Gradually, that unholy marriage is joined by a chorus of mangled voices and a buried thumping house beat, both of which steadily increase in presence. Then, both the garage rock riffage and bass line abruptly vanish, leaving only a thumping four-on-the-floor beat, thick doom-y distortion, and an intense cacophony of voices that sounds like a riot of the damned. Amusingly, it sounds like there is a cowbell incorporated into the murky, buried beat. Detourning a sexy dance beat into a pulsing, unhinged nightmare is an unexpectedly wry (and effective) move, displaying an impish side to Kneale that has historically been well-concealed. Eventually Campbell casts the beat aside, leaving only an anguished, smoldering wreckage of feedback and howling voices.

This is a significant creative step forward, as the inclusion of dark humor, ruined melodies, and pop music snippets, as well as the increased role of electronics and field recordings, show that Kneale's singularly uncompromising and infernal vision still has a great deal of room left for expansion. Fucking Dracula Teeth is yet another great record by one of the current reigning high priests of unpleasantness.

Samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

On their third album, Trembling Bells explore traditional folk themes such as boozing, loneliness, landscape, mystical creatures and regret, with more modern and eclectic sounds. Their joyous approach to playing and singing is hypnotic and passionate with enough humor and raw edges to steer well clear of being over-sentimental.

On their third album, Trembling Bells explore traditional folk themes such as boozing, loneliness, landscape, mystical creatures and regret, with more modern and eclectic sounds. Their joyous approach to playing and singing is hypnotic and passionate with enough humor and raw edges to steer well clear of being over-sentimental.

Trembling Bells’ debut release contained my favorite song of 2009, the sorrowful yet uplifting dirge "Willows of Carbeth." I consciously avoided their second album (lest it somehow conspire to ruin my love for that one song) but am happy to report the group is in good form for The Constant Pageant. The passion is evident from the first piece "Just As The Rainbow" which opens with guitar wailing like bagpipes on heat and the group keeping up an impressive, slow, bombastic pace. Enter the possessed floral gargle that is the voice of Lucretia Blackwell, oft wrongly compared to that of Sandy Denny. While both can conjure a haunting loneliness Blackwell’s is more unpredictable, less pure sounding, and more liable to trilling leaps and guttural bounds. Her adventurously risky singing suits Trembling Bells to a tee since the group repeatedly shift gears and introduce somewhat unconventional instruments onto the solid traditional folk upon which their music is based. "Where Do I Go From You," for instance, includes horns, piano and wild fuzzy guitar but Blackwell’s voice ensures the essential folk aspect can’t be missed, even when she goes into some kind of ecstatic overload repeating the title during the fade-out section.

For contrast, drummer Alex Neilson also sings, both alone and, to fine effect, in harmony with Blackwell. He has featured in a number of other projects including Scatter and Directing Hand but his love of folk music is clearly blood-deep. Neilson is from Yorkshire (from whence came such bastions of folk music as Martin Carthy and the Waterson family) and lovely references to the county, and to other places in England, abound. "Goathland" not only brings to mind the Half Man Half Biscuit song "We built this village on a Trad. Arr. tune" but also name-checks several locations, including itself and Robin Hood’s bay. The later is home (amongst other things) to The Pigsty, one of the most memorable smaller properties restored and available for holiday rental by the non-profit conservation group Landmark Trust.

Trembling Bells show themselves to be unafraid to make a stirring noise and to quote or borrow from 1960s pop music and 1970s progressive rock. They balance deep folk tradition (even the use of brass nods to the tradition of bands attached to the coal mines) with an unabashed love for the sheer power of electric instruments. I can't help but feel that the Watersons themselves might approve. Certainly Mike Heron (of The Incredible String Band) does, if recent joint concerts are any guide. Indeed, the only thing that has me brassed off about this album is the line "wasted my days in watering holes," because the idea that time spent in a good pub could ever be considered a waste, is nonsense to an Englishman.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

On last year's excellent Fountain, Grody divided his time between nods to droning contemporary ambient and more traditional acoustic guitar fare.  This time around, the focus is much heavier on his more rustic, Takoma-influenced leanings, which yields mixed results.  On one hand, these songs are more distinctive and anachronistic, but their languid pace and comparative lack of hooks blunts their impact a bit. In Search of Light still boasts some wonderful songs though–they're just a bit more sparingly distributed than they were on its predecessor.

As far as opening songs go, Grody could not have done much better than the wistful and languorous waltz of "Hello From of Everywhere," which beautifully weaves together bittersweet synth buzz and a nicely harmonized descending guitar melody.  Despite ending a bit sooner than I would have liked, it is pretty much the embodiment of everything Danny does well, which set my expectations for the rest of the album almost impossibly high.  In a few instances, such as the gentle and dreamlike "China Beach," he manages to deliver on that huge initial promise.  "Stars Gaze," the album's sole foray into shimmering ambiance, is quite beautiful as well.  Unfortunately, there are also several pieces that sound to me like a key component is absent.  In the otherwise excellent "Orbits," for example, Grody creates a nice pulse with a pleasantly chiming arpeggio progression, but leaves out a strong melody.  It still works in the sense that it is likable and derives a cumulative power from intelligent repetition, but it definitely falls short of the heights reached elsewhere on the album.

A few other pieces miss the mark a bit more conspicuously though, mostly when Grody indulges an urge to lazily meander or incorporate psych elements– he does both on "Ohr," lamentably.  My lukewarm feelings regarding some of the other pieces are probably attributable to a widening gulf between my taste and Danny's taste rather than questionable artistic decisions though: I am simply not a huge fan of  the '70s Takoma roster to begin with (Robbie Basho, love of raga, etc.), and Grody seems to have appropriated much of that aesthetic minus the blues and ragtime elements that gave that milieu much of its gravitas and vibrancy.  I definitely get the sense that Danny is converging towards some kind of kora/folk/minimalism amalgamation that is all his own, which puts me in the curious position of being disappointed to see someone evolving towards a more original aesthetic (he is misfiring with honor and vision!).  This wouldn't bother me nearly so much, naturally, if I didn't love the other facets of his sound– change is hard when the status quo is desirable.  Thankfully, he has not reached that hypothesized ultimate stylistic destination just yet. In Search of Light may be a so-called "transitional" album, but it is happily still a half-great one.

Samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This stripped-down 20-minute EP captures Blackshaw back near the top of his game, finding the perfect synergy between his talents as a steel-string virtuoso and his ambitions as a more varied composer.  While the overall feeling of these two pieces is languorous, melancholy, and impressionistic, the crisp sound and complex and inventive arrangements imbue them with a surprising amount of dazzle and immediacy.  James makes a virtue of brevity, as Holly is a complete, undiluted, and consistently strong effort.

In some regards, Holly is very much a return to Blackshaw's roots, as his acoustic guitar playing again takes center stage.  Also, it is very nearly an entirely solo affair, enlisting only multi-instrumentalist/All is Falling alum Charlotte Glasson to fill out the sound. Despite that, these two pieces have little in common with the Eastern-tinged American steel-string folkies that inspired James' earliest work.  Instead, Holly fits comfortably (not regressively) into Blackshaw's career arc, feeling very much like a neo-classical guitar album– Blackshaw even plays nylon string here for the first time.

Fortunately, close similarities to Julian Bream and John Williams fall by the wayside once James picks up enough momentum.  "Holly," for example, begins with a deceptively somber twelve-string guitar motif before quickly spiraling off into an roiling web of lightning nylon string arpeggios and descending piano chords.  I was especially struck by the way the incredibly fast and complicated fingerpicking is counterbalanced by the rather languid piano and violin themes– it gives the piece an unusual sense of motion and urgency.  While certain passages in "Holly" are quite beautiful compositionally, the main attraction for me lies in the blindingly dexterous and multilayered cascade of notes employed to unfold the piece's simple melodies.  This is essentially a mesmerizing performance that also happens to be a good song.

"Boo, Forever" is a bit less awe-inspiring technique-wise, but it is cut from roughly the same cloth and is no less enjoyable.  The key difference is that it is built around a few layers of 12-string steel guitars, which gives it an added crisp physicality.  Also, the melodic crescendos feature woodwinds rather than violins, but the general mood remains the same.  Exactly what that mood is, however, is somewhat difficult to put my finger on.  It is impossible to say how much the Christmas-connotations of "holly" have colored my judgment at this point, but I think these two pieces definitely evoke a cozy, huddled-near-a-fireplace-on-a-cold-winter-day feel that is quite appealing (even when co-mingled with muted sadness).  In fact, the worst thing that I can possibly say about this release is that it may err on the side of being too polite, but I can find room in my heart for "nice" things if they are well-executed.  While it doesn't quite reach the heights of some of Blackshaw's individual pieces from the past, Holly is certainly an inspired detour (and a very solid one at that).

Samples:

Read More