- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I had admittedly become a bit numb to this prolific Kenyan producer’s steady stream of ambient releases in the years since he first burst onto the scene with 2020’s Peel, but this second Editions Mego album is one hell of a stunner. Fittingly, Kin first began to take shape in 2021 when KMRU discussed his vision for Peel’s sequel with label head Peter Rehberg, but that particular vision was unsurprisingly put on ice with Rehberg’s untimely passing. After about a year, however, KMRU gradually returned to that material and a rather different and noisier vision began to take shape instead. Partially inspired by distorted guitar sounds of KMRU’s youth, the viscerally snarling and smoldering Kin sounds like one of his stronger ambient albums was doused with gas and set ablaze. Fittingly, that vision is reminiscent of some of the best bits of Pita’s Get Out and Rehberg’s former bandmate Christian Fennesz turns up to the party as well, which makes Kin feel like both KMRU’s finest album to date and an improbable late-period return to Editions Mego’s golden age.

I had admittedly become a bit numb to this prolific Kenyan producer’s steady stream of ambient releases in the years since he first burst onto the scene with 2020’s Peel, but this second Editions Mego album is one hell of a stunner. Fittingly, Kin first began to take shape in 2021 when KMRU discussed his vision for Peel’s sequel with label head Peter Rehberg, but that particular vision was unsurprisingly put on ice with Rehberg’s untimely passing. After about a year, however, KMRU gradually returned to that material and a rather different and noisier vision began to take shape instead. Partially inspired by distorted guitar sounds of KMRU’s youth, the viscerally snarling and smoldering Kin sounds like one of his stronger ambient albums was doused with gas and set ablaze. Fittingly, that vision is reminiscent of some of the best bits of Pita’s Get Out and Rehberg’s former bandmate Christian Fennesz turns up to the party as well, which makes Kin feel like both KMRU’s finest album to date and an improbable late-period return to Editions Mego’s golden age.

The opening “With Trees Where We Can See” provides a fairly representative (if condensed) introduction to Kin’s pleasures, as a thick and viscous-sounding synth motif languorously loops while a crackling and sizzling veil of distortion steadily intensifies. While that is hardly groundbreaking territory in the “power ambient” realm, KMRU’s approach is a bit more layered and mysterious than most, as a whistling and howling melody gradually starts to emerge from the sea of noise. While that particular piece clocks in at a mere three minutes in length, the overall trend throughout the album is that the longer pieces tend to undergo the most magical and sublime transformations (though the 20-minute closer “By Absence” is a more improvisatory and bird song-enhanced exception to that rule).

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest album from Christian Schoppik feels like a bit of a curious outlier or comparatively modest release in the wake of last year’s stellar Unterhaltungen Mit Larven Und Überresten, but it is a characteristically fascinating one nonetheless. Schoppik’s collaborator this time around is Matthias Kremsreiter, who debuts his new Roudi Vagou alias but normally records as alibikonkret. While the two artists certainly share a fondness for dark psychedelia and haunted atmospheres, Taghelle Nacht (Daylight Night) feels like a completely new vision that suggests a Bavarian twist on Grey Gardens experienced from the perspective of a ghost and DJed by The Caretaker’s haunted Victrola: a slow-motion drift through the moldering, dust-covered ruins of a once-opulent seaside mansion in which vivid memories of the past continually bleed into the present in subtly unsettling and hallucinatory fashion.

This latest album from Christian Schoppik feels like a bit of a curious outlier or comparatively modest release in the wake of last year’s stellar Unterhaltungen Mit Larven Und Überresten, but it is a characteristically fascinating one nonetheless. Schoppik’s collaborator this time around is Matthias Kremsreiter, who debuts his new Roudi Vagou alias but normally records as alibikonkret. While the two artists certainly share a fondness for dark psychedelia and haunted atmospheres, Taghelle Nacht (Daylight Night) feels like a completely new vision that suggests a Bavarian twist on Grey Gardens experienced from the perspective of a ghost and DJed by The Caretaker’s haunted Victrola: a slow-motion drift through the moldering, dust-covered ruins of a once-opulent seaside mansion in which vivid memories of the past continually bleed into the present in subtly unsettling and hallucinatory fashion.

As befits an album with such a mysterious and elusive vision, Taghelle Nacht is divided into two halves (like a split release) with Roudi Vagou credited with the first eight pieces and Läuten der Seele with the rest, but the differences between the two artists are so blurry that they are largely irrelevant. The reason for that is two-fold, as the album feels like a series of impressionistic vignettes shaped from the same small palette of samples and instruments and the more melodic bits tend to flicker and vanish like phantoms (“snatches of song drift by like dreamlike fragments, and achingly tender flourishes fleetingly appear and retreat”).

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This mesmerizing opus from NYC-based composer Irisarri first began its life with a chance meeting at MUTEK in Mexico City, as a conversation with Dutch media artist Jaco Schilp regarding how technology shapes perception led to an invitation to a collaborative residency at Uncloud (located in a former psychiatric prison in Utrecht). Appropriately, that original topic relates closely to the album’s overarching concept, as Points of Inaccessibility reflects the pervasive isolation and alienation that has resulted from living illusory digital lives (“we inhabit spaces saturated with signals, yet the possibility of genuine contact becomes increasingly remote”). Schilp’s visual research also played a significant role in the album’s shape, as Irisarri’s sounds were processed through “custom point-cloud software patch that produced images in continuous flux” in which “visuals flickered, dissolved and reformed like memories that resist coherence, functioning as a digital Rorschach that reflected the observer’s own perception.” The music achieves a very similar end, as warm and beautiful forms endlessly blossom and dissolve in a roiling ocean of static.

This mesmerizing opus from NYC-based composer Irisarri first began its life with a chance meeting at MUTEK in Mexico City, as a conversation with Dutch media artist Jaco Schilp regarding how technology shapes perception led to an invitation to a collaborative residency at Uncloud (located in a former psychiatric prison in Utrecht). Appropriately, that original topic relates closely to the album’s overarching concept, as Points of Inaccessibility reflects the pervasive isolation and alienation that has resulted from living illusory digital lives (“we inhabit spaces saturated with signals, yet the possibility of genuine contact becomes increasingly remote”). Schilp’s visual research also played a significant role in the album’s shape, as Irisarri’s sounds were processed through “custom point-cloud software patch that produced images in continuous flux” in which “visuals flickered, dissolved and reformed like memories that resist coherence, functioning as a digital Rorschach that reflected the observer’s own perception.” The music achieves a very similar end, as warm and beautiful forms endlessly blossom and dissolve in a roiling ocean of static.

Notably, Schilp’s own process required “a continuous stream of sound in real time,” so Irisarri’s initial recordings at Uncloud were mostly of bowed guitar drones processed through various pedals and looping systems. Admittedly, that approach sounds like business-as-usual for Irisarri, but the album continued to evolve further once he returned to his home studio, as he fleshed out the original recordings with synth, Moog bass, and strings while remaining as faithful as possible to the original performances.

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

Infrasound, or frequencies of sound that exist beyond the range of human hearing, are omnipresent but cannot be heard, nor recorded using traditional equipment. Captured over a period of 24 hours in Amherst, Massachusetts (coincidentally, a town adjacent to mine, and that I drive through multiple times per week), Brian House captured infrasound via custom built macrophones, speeding the recordings up 60 times to render them into the range of human hearing. The outcome is an expansive, at times terrifying, pair of compositions that are as sonically enjoyable as they are scientifically fascinating.

With the sides split between day and night, the differences are audible dependent on the time of recording. The day side (6AM through 6PM) leads in with silence that is soon blended with distant, heavy rumbling and other low frequency, submerged like sounds. Slow passages of sound whiff over like clouds, offsetting unconventional echoing sounds. Through the 24 minutes of the piece, House captures higher frequency tones, indistinct rattling, and guttural textures. The overall structure is a consistent one, however, even with all of these disparate layers mixed with a strong compositional structure.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This genre-blurring Dutch quartet describes their sound as a “joyous mix of disco, funk, surf, psychedelia, and Southeast Asian motifs,” but the way those influences are juggled and balanced has been in a continual state of flux since the band’s earliest singles. That stylistic volatility seems to be by design, however, as co-founder/drummer Kees Berkers notes that the band’s name differs from Yin Yang in that it alludes to “two negative forces that cannot reach a common ground” and that the band’s mission is about “finding a balance in the unbalanced.” Unsurprisingly, that approach has resulted in a bit of hit-or-miss discography over the years, but Yīn Yīn can be a hell of a great band when all of their colliding influences come together just right. In this case, the band’s unbalanced balance most often sounds like an excellent surf guitarist backed by a solid disco rhythm section and it characteristically yields yet another handful of fun and eclectic singles.

This genre-blurring Dutch quartet describes their sound as a “joyous mix of disco, funk, surf, psychedelia, and Southeast Asian motifs,” but the way those influences are juggled and balanced has been in a continual state of flux since the band’s earliest singles. That stylistic volatility seems to be by design, however, as co-founder/drummer Kees Berkers notes that the band’s name differs from Yin Yang in that it alludes to “two negative forces that cannot reach a common ground” and that the band’s mission is about “finding a balance in the unbalanced.” Unsurprisingly, that approach has resulted in a bit of hit-or-miss discography over the years, but Yīn Yīn can be a hell of a great band when all of their colliding influences come together just right. In this case, the band’s unbalanced balance most often sounds like an excellent surf guitarist backed by a solid disco rhythm section and it characteristically yields yet another handful of fun and eclectic singles.

Amusingly, Berkers notes that a formative event in this project’s history was the discovery of “a couple of compilation albums of psychedelic ‘60s and ‘70s guitar music from Southeast Asia” which led them to “YouTube channels where we couldn't read anything because everything was in Thai letters or in Chinese symbols– and that felt like we found the treasure!” Predictably, I was sucked down a very similar rabbit hole myself many years ago by Soundway’s The Sound of Siam compilation and I am struck by the Ouroboros-like cycle of influences on display here: so much great music came out of Southeast Asia and Africa in the ‘60s and ‘70s because traditional music collided with an influx of Western pop influences and enterprising artists eagerly borrowed and assimilated all of the hip new sounds that they could find.

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

Ian Wellman chose a distinctive and fitting title for his first vinyl LP, given the context in which it was composed. Recorded during the devastating Palisades and Eaton fires in California, which engulfed huge stretches of the state in early 2025. Focused on capturing the Santa Ana winds that spread the fires (I’m trying to not make a Steely Dan reference here) and helped them to last for nearly a month, Particularly Dangerous Situation (named for an unprecedented weather forecast in the area) is simultaneously an audio document as it is a narrative composition, it is a captivating, but harrowing work to say the least.

The basic structure of the album features Wellman alternating between treated tapes and beautiful tones, and roaring recordings of wind, segued together into what feels more like two side-long compositions. Fittingly, the opening "Intro" captures a blast of winds resembling pure white noise, with an occasional crackling sound that hints at the destruction in the distance. The roar fades into "Particularly Dangerous Situation" as a somber, sustained tone that heralds the bleakness of the event. The melancholy sound is blended with the blast of winds, with the musical passages eventually disrupted by a heavy amount of distortion.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

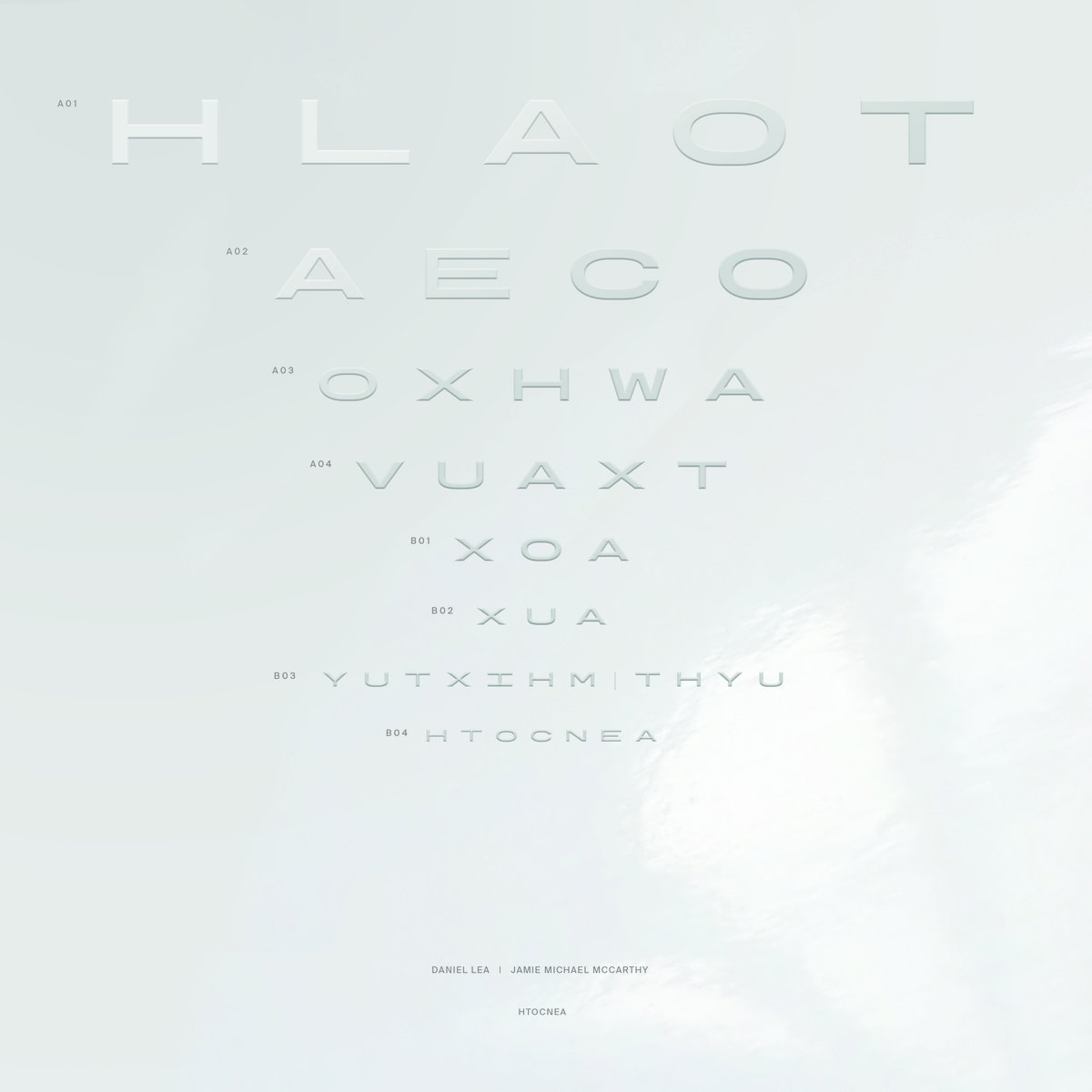

I first encountered Los Angeles-based composer Daniel Lea through L A N D’s excellent Anoxia album back in 2015, but he has become considerably more prolific in recent years after launching his own Vast Habitat imprint. This first collaboration with London-based violinist/cellist Jamie Michael McCarthy has apparently been a decade in the making and borrows both its title and some of its ingenious inspiration from an eye test chart that McCarthy found on the street. On its face, the resultant album has the shapeshifting moods and immersive spell of an art-damaged science fiction score, but immersive headphone listening reveals a considerably deeper and more compelling vision lurking within. Part of that is due to Lea’s considerable sound design talents and inventive assimilation of influences ranging from austere dub techno to avant-garde piano composers and contemporary electronic heavy hitters like Ben Frost and Tim Hecker, but the unusual structural dynamics of these pieces are quite unique and mirror the shifting depth of field that one might get from experimenting with different lenses.

I first encountered Los Angeles-based composer Daniel Lea through L A N D’s excellent Anoxia album back in 2015, but he has become considerably more prolific in recent years after launching his own Vast Habitat imprint. This first collaboration with London-based violinist/cellist Jamie Michael McCarthy has apparently been a decade in the making and borrows both its title and some of its ingenious inspiration from an eye test chart that McCarthy found on the street. On its face, the resultant album has the shapeshifting moods and immersive spell of an art-damaged science fiction score, but immersive headphone listening reveals a considerably deeper and more compelling vision lurking within. Part of that is due to Lea’s considerable sound design talents and inventive assimilation of influences ranging from austere dub techno to avant-garde piano composers and contemporary electronic heavy hitters like Ben Frost and Tim Hecker, but the unusual structural dynamics of these pieces are quite unique and mirror the shifting depth of field that one might get from experimenting with different lenses.

The opening “H L A O T“ provides an especially illustrative introduction to the duo’s slowly blossoming vision, as it deceptively opens with deep dark ambient exhalations before some smearing and curdled higher frequencies unexpectedly give way to a series of lingering, murkily dissonant piano arpeggios. From there, the piece gradually develops into a sort of slow-motion and noirish strain of piano jazz ravaged by snarling and roiling eruptions of Hecker-esque distortion. That unsurprisingly proves to be quite an effective combination, but the piece’s best moments do not happen until after the structure completely collapses and distends to leave behind only heaving seismic rumbles, scrabbling string noise, crackling distortion, and deep and rolling bass throbs.

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

The Weightless Sea is the fourth album from the duo of multiinstrumentalists Eric Hardiman (Rambutan, Sky Furrows, Century Plants) and Michael Kiefer (More Klementines). They continue their journey through the vastness of space (or in this case the depth of the ocean) with their guitar/bass/electronics/drum approach, , coupling solid rhythmic elements with more improvised sounding guitar and electronics makes for an amazingly fascinating record.

Twin Lakes/Feeding Tube/Cardinal Fuzz

Opener "Materialized" sets the stage perfectly with Kiefer’s metronomic, steady drumming and Hardiman taking double duty with an anchoring bass line that occasionally comes to the forefront and layers of fuzzy, overdriven guitar. The drumming is switched up throughout and while the song has a steady flow to it, never becoming too repetitive. The other shorter (meaning less than five minutes) song on here, "Sleepwalker," is the perfect counterpart. A relatively basic melody, albeit a memorable one, drives the song into what hints at the best of 1970s rock music without ever sounding too similar or trite.

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

The latest album from Ralf Wehowsky is unsurprisingly a bit of a challenging listen, but even more so than I would have expected. Fading Pictures is not a particularly dense or noisy recording, but the more extreme elements, even in the frequently sparse context of the compositions here, give it a distinct feel even within his diverse and complex body of work, rife with tension that works perfectly.

One of the most pronounced facets of Fading Pictures is Wehowsky’s frequent use of higher frequencies, especially in the context of shrill, feedback like passages that feature throughout. Not sustained, but rising and falling in multiple pieces, linking them together. Right from the opening moments of "Ertäumets Intro, Vorzeitig Abgebrochen" this is apparent: high pitched layers paired with bassy crumbles and other sonic apparitions of sound that float through. Towards the end he mixes in some bizarre, almost laughing type noises to make things all the more unsettling.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest EP from the ever-compelling Diamanda Galás has had quite an interesting journey, as it first began its life in an evolving larger work entitled "Das Fieberspital (The Fever Hospital)," which is a “musical setting of Georg Heym’s early 20th Century expressionist poem about patients stigmatized by yellow fever.” At some point, however, Galás concluded that “the piano skeleton had become its own work” and its (mostly improvised) performance was released as De-formation: Piano Variations back in 2020. Five years later, she was inspired to ambitiously rework that piece for a Paris performance at the Pinault Collection celebrating the legacy of fellow iconoclastic composer Maryanne Amacher. Now in deconstructed, reconstructed, and characteristically volcanic new form, De-formation: Second Piano Variations presents Galás’ “definitive” performance of that visceral tour de force.

This latest EP from the ever-compelling Diamanda Galás has had quite an interesting journey, as it first began its life in an evolving larger work entitled "Das Fieberspital (The Fever Hospital)," which is a “musical setting of Georg Heym’s early 20th Century expressionist poem about patients stigmatized by yellow fever.” At some point, however, Galás concluded that “the piano skeleton had become its own work” and its (mostly improvised) performance was released as De-formation: Piano Variations back in 2020. Five years later, she was inspired to ambitiously rework that piece for a Paris performance at the Pinault Collection celebrating the legacy of fellow iconoclastic composer Maryanne Amacher. Now in deconstructed, reconstructed, and characteristically volcanic new form, De-formation: Second Piano Variations presents Galás’ “definitive” performance of that visceral tour de force.

I will admit that I had somewhat modest expectations for this release, as this piece had already been released once and solo piano performances can often be quite a tough sell for me in general. Given that this particular pianist is Diamanda Galás, however, I figured that there must be something special enough about this piece to necessitate an ambitiously sharpened and re-shaped re-recording. Characteristically, of course, this performance is indeed mesmerizing and incendiary enough to warrant a resurrection, but I was legitimately fascinated by how much time and passion Galás poured into reworking “De-Formation” long before the Paris performance ever took place. Aside from “blasting through the original structure…block by block” and “sculpting the muscle of the source material” to create new phrasings and degrees of dynamic intensity, Galás also enlisted “a specialist in notating difficult piano music” (Thomas Feng) to create a score for the oft-improvised original recording and spent literal months experimenting with various foot pedal combinations.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

To celebrate the remastered tenth anniversary reissue of his 2015 opus A Fragile Geography, Rafael Anton Irisarri invited an eclectic murderers’ row of his friends and peers to work their transformative magic on his source material. That was a bit of a bold and inspired decision given that the original album is quite bleak and grayscale in nature, but Irisarri’s well-chosen group of reinterpreters found a number of fresh and inventive ways to highlight their most inspired bits or sharpen them into something that beautifully transcends their original inspiration. To my ears, Abul Mogard and Kevin Martin largely steal the show with their killer contributions, but this whole album is a quite a fascinating companion piece to one of Irisarri’s most celebrated albums (and even manages to surpass it on several occasions).

To celebrate the remastered tenth anniversary reissue of his 2015 opus A Fragile Geography, Rafael Anton Irisarri invited an eclectic murderers’ row of his friends and peers to work their transformative magic on his source material. That was a bit of a bold and inspired decision given that the original album is quite bleak and grayscale in nature, but Irisarri’s well-chosen group of reinterpreters found a number of fresh and inventive ways to highlight their most inspired bits or sharpen them into something that beautifully transcends their original inspiration. To my ears, Abul Mogard and Kevin Martin largely steal the show with their killer contributions, but this whole album is a quite a fascinating companion piece to one of Irisarri’s most celebrated albums (and even manages to surpass it on several occasions).

Notably, this reworked version of A Fragile Geography mirrors the sequence of the original pieces, which means that each artist was tasked with reworking a different piece and that the overall arc of the album remains largely intact (albeit significantly transformed as well). There is also a bit of a loose trajectory towards departing more and more dramatically from the source material as the album unfolds, as the first two pieces are largely nuanced and subtle enhancements rather than complete overhauls.