- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Crow Eye Hint is a drone record. One track which uses the noise and resonance of

a piano when sustain pedal is relaesed and depressed.5 minutes into this there is

a few second burst of two tone riff, than the piano innards soundscape returns.

After reaching a climax it gives way a single note on the same instrument develops

through repetition into a pleasant drone inviting strings. At a precise moment

tonality of texture lifts by a semitone and develops further.

From depths a permutation of the original theme returns adding an extra element of

forward propulsion until a natural conclusion is reached after 54 minutes

and a few seconds.

Handmade cover.

price 15 Euro including shipping worldwide.

you can get it from: www.aranos.org

There is an mp3 of the whole record there, but it seems to load very slowly, as it is 54 minutes long!

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

In 2006, the rather enigmatic and aberrant Mudboy recorded a live session for the Dutch radio station VPRO, but it took three years for it to finally see release. Upon hearing this odd and uneven set, that delay seems quite justified- there are certainly some moments of sublime beauty and weirdness captured here, but they are few and far between. This probably should have stayed in the vault.

In 2006, the rather enigmatic and aberrant Mudboy recorded a live session for the Dutch radio station VPRO, but it took three years for it to finally see release. Upon hearing this odd and uneven set, that delay seems quite justified- there are certainly some moments of sublime beauty and weirdness captured here, but they are few and far between. This probably should have stayed in the vault.

Mudboy is an organist and installation artist based in Providence, RI. As there are not many working organists in the experimental music underground, he pretty much had his own niche claimed the moment that he started releasing music roughly a decade ago. However, the uniqueness of Mudboy’s aesthetic goes far beyond his anachronistic choice of instruments and permeates absolutely everything he is involved in: his performances, his installations, his general vision, his sounds, and his cover art are all pretty uniformly bizarre and unique. In this case, he uncharacteristically did not seem to have had a hand in the album art, but Staalplaat’s three-panel wooden case is quite nice in an elegantly minimal way regardless.

There are five distinct songs collected here, lasting for roughly half an hour. I do not have a comprehensive command of Mudboy’s complete oeuvre of limited edition vinyl, cassettes, and CD-Rs, but it seems almost certain that the session was totally improvised on the spot with a minimum amount of both preparation and gear. That is the only logical explanation for the opener “Ntro,” which completely falls flat and goes nowhere for over four minutes (it basically approximates a muttering goblin repeatedly sounding a tuning fork). The following piece (“B.O.G.”) initially yields similar dire promise, as it sounds like that same rasping, gibbering goblin has now begun fiddling with the presets on a cheap Casio.

Unexpectedly, however, “B.O.G.” quickly evolves into the session’s clear highlight, as Mudboy plunges into an utterly mesmerizing organ solo atop the cheesy, carnivalesque vamp. I don’t know quite what he did to his organ to get it to sound like it does (he is an avid circuit-bender and instrument modifier), but I have never heard anything quite like it. The notes seem to be almost solid, like they are hanging in the air and slowly dripping to the ground. Sadly, that snatch of heaven is all too ephemeral and the remaining three pieces (while not bad) fail to recapture much magic.

The best of the remainder is probably “Beebbub,” a buzzing and throbbing noise piece built upon treated field recordings of bees. The aural apiary is gradually populated by a barrage of deranged and incomprehensible speech snippets that echo and bounce all over the place, evoking the feeling of a disturbingly psychedelic funhouse. The other two songs are fairly one-dimensional and unmemorable: “Osandways” is essentially a prog-rock organ solo without a surrounding song, while the accordian-esque “Shantysea” resembles one of Terry Riley’s more annoying and dated-sounding excursions.

The central problem with this session is that each piece seems to consist of one idea that is flogged away at until Mudboy loses interest in it. Some of the ideas are good and some aren’t, but there is very little in the way of progression in either case. Essentially he creates a loop, makes some sounds over it for a few minutes, then stops. While I realize that may be a somewhat inherent problem with one-man live improv, it doesn't make for a compelling listen when divorced from the performance itself. Obviously, there is a lot to like here from a pure sound perspective, but those sounds get dull quickly when there is little structure and movement surrounding them. This is definitely not Mudboy’s finest moment, but thankfully it is also not a particularly representative one.

Samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This is a fun album. It takes a high art concept and makes it playful. Albums that are made up purely of percussion are few and far between as it is, and the fact that the instrument in question here is the Mid-Hudson Bridge makes this a rare bird indeed.

This is a fun album. It takes a high art concept and makes it playful. Albums that are made up purely of percussion are few and far between as it is, and the fact that the instrument in question here is the Mid-Hudson Bridge makes this a rare bird indeed.

On the first listen I was surprised by the cleanliness of the sound. It wasn’t as distorted or as jarring as I had expected. Although the source material was recorded in the field, to say that it is made up of field recording of a percussionist on a bridge would give the wrong impression. I originally thought that songs were somehow performed and captured live, but for a single person to play all the different sounds in real time would have been an impossible feat. The last track though features the composer talking about how the project was executed. Listening to him talk sounded a bit like being on a field trip or a tour—in fact the packaging of the CD looks like something found in a museum gift shop—but was nonetheless informative of his process. All the sounds except for one were recorded using a contact microphone. Every available surface was used from signs, to metal grates, to the thick and tightly wound steel of the suspension cables. The only sounds recorded with an open air mic were of small round objects like BBs and air gun pellets (among other things) poured down one of the bridges shafts, transforming it into a gigantic rain stick. After all of the source material was recorded it was assembled in the studio. Like a jigsaw puzzle the pieces fit together perfectly.

The notes derived from the bridge may not have the widest of range, but the rhythms bewilder with their compact variability. This is high energy music. Even as the tempos vary, speeding up and slowing down, deep thunderous pulses continue to pound into the brain. “The River That Flows Both Ways” begins with a low rumble in the background, and the sound of banging hammers. Overlaid atop is a melody that could have been played on a kalimba but it is not. “Rivet Gun” is Bertolozzi’s answer to slick electronic dance club music. Rapid fire machine gun pulses take the place of the hi-hat, and cacophonous smashes of iron girders stand in for the 4-to-the-floor bass kicks. There are even staggered thrums and throbs that create a time stretch illusion harkening back to the hey-day of drum ‘n bass songs where every other phrase contained a time stretched beat. “Dark Interlude” is a muted piece mainly in the lower register without sharp noises or the reverb laden clanging that features on other songs. Without keeping a steady beat, it reminds me of a broken metronome or a clock whose gears have shifted into keeping an alternate time, a freeform experiment in non-linear drumming.

The composition of “Bridge Music” has also culminated in an installation located at the FDR Mid-Hudson Bridge itself. It consists of two listening stations where pedestrians crossing the bridge can listen to any of the eleven tracks featured on this CD. The other element is a continuous stereo broadcast of the music on 87.9 FM available in the two parks that abut the bridge, Waryas Park in Poughkeepsie, and Johnson-lorio Park in Highland.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Coldkill is the duo of Rexx Arkana (FGFC820) and Eric Eldredge (Interface), and was created as an attempt to get back to the roots of EBM and 1980s industrial music, an era from which both musicians have drawn influence throughout their careers]. With the use of vintage gear and a more minimalistic aesthetic when it comes to construction and dynamics in these songs, they do an exemplary job of being forward thinking, yet still clearly acknowledging their past.

Coldkill is the duo of Rexx Arkana (FGFC820) and Eric Eldredge (Interface), and was created as an attempt to get back to the roots of EBM and 1980s industrial music, an era from which both musicians have drawn influence throughout their careers]. With the use of vintage gear and a more minimalistic aesthetic when it comes to construction and dynamics in these songs, they do an exemplary job of being forward thinking, yet still clearly acknowledging their past.

Arkana especially has been one of the unsung heroes of the genre.Working as a promoter and DJ since the 1980s, as well as helming EBM supergroup Bruderschaft, his contributions to both the industrial scene and its antecedents has largely been overlooked.Which is a significant oversight, because his dedication to the style and his skills in creating it shine through distinctly on Distance by Design."In Here" makes this abundantly clear, with his intentionally flat, disconnected vocals capturing the early days of synthpop and new wave perfectly, as a steady 4/4 beat and tight sequenced layers dominate the song.

"Black or White" is another standout from the first moments of metallic synth and analog bassline.The additional keyboards added and cheap drum machine also go a long way in capturing the 1980s vibe, as do the vocals.Here Arkana's approach is just the right amount of off-kilter in delivery, sounding not unlike Al Jourgensen during Ministry's transitional period from With Sympathy to Twitch (which is, as far as I am concerned, far and away their best era).The chintzy drum machine reappears on "Fables", but here in a slower, more depressive context overall.With strong melodies and nice outbursts in the chorus, there is a great shifting dynamic throughout.

For other songs here, the duo bring out some more modern sounds, while still keeping the nostalgic elements fully in play."Angel Unaware" is a mix of classic stiff beats and modern sounding synth melodies, but rounded out nicely with a bit of undeniable FM synthesis sounding bass towards the end of the song."I'm Yours" again has more of a contemporary sounding synth lead throughout, but the mix and production is sparse enough to capture that vintage feel the duo embraces throughout.

Some of the other standout moments for me were where Arkana and Eldridge seemed to step furthest out of their comfort zone."Memories" is all robotic voice samples and showcases traditional pop sensibilities, made all the more compelling by a Kraftwerky chorus that is extremely memorable."Leave It All Behind", on the other hand, is more of a percussive beast, with programmed drums and percussive synth leading the way.But around this is some Latin/House tinged layers and even a bit of piano at the end, culminating in some very disparate, yet somehow complementary styles.

Two remixes also appear on the album, with stalwarts Assemblage 23 reworking "In Here" and Covenant taking on "I'm Yours".Thankfully, the approach to remixing is thematically consistent with the rest of the record, because unlike many of today’s modern remixes, both retain most of their original elements.They are reshaped to be somewhat more club friendly, but neither are significant departures from the source material.Assemblage 23’s version of "In Here" is particularly the standout, with the chorus expanded even more and the addition of orchestra hit samples really driving the vintage feel home.

As I have stated in other reviews, I tend to not follow the current industrial scene too closely, preferring some of the genre's outliers that are making music more consistent with what I grew up listening.Which is exactly why Distance by Design worked so well for me, since Rexx Arkana and Eric Eldredge not only channel those early days so well via Coldkill, but also knowing Arkana was an actual participant in the genre during its earliest days.The album stands strongly on its own, but having that genuine old school credibility is a nice added bonus as well.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Alex Keller and Sean O'Neill may have been collaborators since 2015, but Kruos is actually their debut release. That relative youth does not translate to lack of experience on the album, however, as the duo’s work is a complex, nuanced work of sound art, conjured up from some rather rudimentary sources, largely just field recordings and a telephone test synthesizer. It is a bit of a difficult, unsettling experience at times, but a strong one nonetheless.

Alex Keller and Sean O'Neill may have been collaborators since 2015, but Kruos is actually their debut release. That relative youth does not translate to lack of experience on the album, however, as the duo’s work is a complex, nuanced work of sound art, conjured up from some rather rudimentary sources, largely just field recordings and a telephone test synthesizer. It is a bit of a difficult, unsettling experience at times, but a strong one nonetheless.

The two halves of Kruos complement each other well, with each side representing some drastically different approaches to sound.The first half begins rather simply with a big, looming bassy analog tone that slowly oscillates in pitch.Sputtering at times, it functions well as an underlying foundation for the processed field recordings to be constructed upon.The duo introduces these rather coarsely via recordings of violent, heavy reverberated knocking.There is a rhythmic quality to it, but is anything but conventional.Instead, it functions as a jarring, menacing addition to initially restrained sounds.

Keller and O'Neill are not just working with pure field recordings, of course, so after some of those loud outbursts, a bit of delay scatters the sound nicely, giving an additional sense of depth.Beyond that, some weird creaking textures and shifting of pitches balance out the open space well, bringing a nicely foreboding quality to the composition.The tones get even more varied and pushed to the forefront, building up to a dramatic, yet abrupt ending.

The second half of the record is the more subtle side to Kruos.The low frequency synthesizer hum reappears, but here blended with an ambience somewhere between white noise generator and air conditioning system.From here slow, sparse pulsations appear, representing another misuse of that telephone test equipment the duo utilizes.Sputtering, rumbling electronics appear, giving a bit more tension to the otherwise peaceful surroundings, but still staying more restrained and less confrontational than the first half.

Eventually these indistinct and mostly unidentifiable field recordings and found sounds are presented in a less treated way, consisting of far off birds and insects that again capture the vastness of nature very well.Towards the conclusion, however, the duo decides to get weird again.There is a reappearance of some of the knocking/clattering type sounds that were heard throughout the first part, building to a more disorienting, chaotic arc before coming to another abrupt conclusion.

Alex Keller and Sean O'Neill may not have used a significant amount of instrumentation to construct Kruos, but they achieve a great deal with what they have.It is difficult and challenging at times, and there is not much to grab on to as far as conventional rhythm or melody, but it excels in abstraction.In many cases the result is far removed from the source material, but the environment the two create on here is just as fascinating as any natural one that could be captured.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The second full-length album from this bass-driven Australian "freak unit" is an intriguing evolution from the bleary, haunted atmospheres of 2015's Hide Before Dinner. For one, the mood is considerably less unnerving, but the trio has also incorporated a significant dub influence (a move that always makes my ears perk up). Naturally, F Ingers is still as unrepentantly bizarre, prickly, and indulgent as ever, but they seem to found a way to make their fractured nightmares feel a lot more playful, spontaneous, and kinetic. At its worst, Awkwardly Blissing Out sounds like a batch of willfully wrong-headed, dub-damaged, and sketchlike experiments that blossomed from the corpses of murdered songs. At its best, however, it transcendently resembles a newly discovered cache of extended and deeply hallucinatory dub remixes of imaginary early UK post-punk classics.

The second full-length album from this bass-driven Australian "freak unit" is an intriguing evolution from the bleary, haunted atmospheres of 2015's Hide Before Dinner. For one, the mood is considerably less unnerving, but the trio has also incorporated a significant dub influence (a move that always makes my ears perk up). Naturally, F Ingers is still as unrepentantly bizarre, prickly, and indulgent as ever, but they seem to found a way to make their fractured nightmares feel a lot more playful, spontaneous, and kinetic. At its worst, Awkwardly Blissing Out sounds like a batch of willfully wrong-headed, dub-damaged, and sketchlike experiments that blossomed from the corpses of murdered songs. At its best, however, it transcendently resembles a newly discovered cache of extended and deeply hallucinatory dub remixes of imaginary early UK post-punk classics.

I have been regularly enjoying Carla dal Forno's gorgeously skeletal deadpan pop for a few years now, but I am embarrassed to say that I only recently began to fully appreciate the unholy alchemy that occurs when she teams up with bassist Tarquin Manek.On pieces like Tarcar's "Visions of the Night," the duo conjure up some of the most menacing and darkly lysergic music in recent memory.Their F Ingers project, where they are joined by Manek's Bum Creek bandmate Samuel Karmel, explores a similarly dark and fragmented vision, but does so in far more primitive and stark fashion.It is a fascinating clash of styles, particularly on the opening "My Body Next to Yours."The bedrock of the piece is Manek's fairly straightforward bass line, which feels like it has been disembodied from an actual catchy song with a real groove.Instead of being joined by a cool beat, however, it finds itself unfolding beneath Karmel’s quavering, seasick-sounding synth motifs and intrusive squalls of spacey electronics.For her part, dal Forno sounds similarly adrift and decontextualized, as her vocals feel distracted and drifting, often overlapping or being chopped into mere word fragments.It essentially feels like Manek showed up eagerly expecting to make a great post-punk album in the Young Marble Giants vein, but his bandmates turned up in either a somnambulant trance (dal Forno) or in the midst of a complete psychotic break from reality (Karmel).On paper, that aesthetic train wreck probably should not work, yet it somehow does.

None of the remaining five songs resembles the opener all that much, but there is definitely an overarching theme throughout of taking the elements of a hooky, well-crafted song and impishly deconstructing them or somehow derailing them into endearing outsider wrongness.For example, "All Rolled Up" brings a drum machine into the mix for a pleasingly burbling groove, but the individual pieces of the song gradually become isolated from one another as the song unfolds.While everything still fits together and sounds melodic, both dal Forno's vocals and Manek's bass sound like they are occurring separately in empty, reverberant rooms.The following title piece also features a simmering groove, but the pulse is mostly built from echoing clicks and it is regularly disrupted with jarring howls of dissonant synths.At some point, a lush synth drone starts to slowly rise in the mix and dal Forno breathily croons a few cryptic lines, yet the components never cohere into anything more concrete than a woozy reverie of skipping delay and hazy drone."Time Passes," on the other hand, sounds like band came up with an actual vocal melody and lyrics, then set about gleefully mangling them with effects, pulling everything apart and stretching the song into a fragmented fantasia of dreamy, hiss-ravaged melody and crazily panning drum machine deconstructions.The album's closer is even more diffuse, as dal Forno’s reverb-swathed vocals hazily float above a pile-up of disjointed strumming and sci-fi-sounding analog synth noodling.

If F Ingers spent the entire time just cheerfully breaking things and crashing their songs into the wall, Awkwardly Blissing Out would still be a fairly compelling and unusual album, but occasionally all their mismatched parts and misused equipment improbably combine to form something beautiful.The aforementioned "My Body Next To Yours" is one such moment.The other comes near the end of the album in the form of "You're Confused," which uses a quietly propulsive groove of handclaps and bass as foundation for a swirling fog of echoing melodies, spectral chords, and chopped-up snatches of dal Forno's vocals.When it hits the mark like that, Awkwardly Blissing Out shares a lot of common ground with Peaking Lights' masterpiece 936, though F Ingers are unquestionably far more aberrant-minded and happy to push their experimentation to a place of more dubious listenability.That is the only real caveat here: playing with structure and texture is the primary focus here and sometimes good songs emerge from that.F Ingers are not terribly concerned if they do not, as long as the results are interesting.As such, this is probably not the place to go to hear any of the participants' finest work, but there are certainly some flashes of brilliance and more outré-minded listeners will find a lot to enjoy in this trio’s mischievous free-form surprises.In fact, Awkwardly Blissing Out feels perversely like an avant-garde/postmodern party album where karaoke is replaced by increasingly adventurous manglings of dour post-punk classics.It admittedly is not as catchy as the original songs might be, but seeing how far out F Ingers are willing to go offers a different and far rarer strain of fun.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Few artists continually push their art into strange and unfamiliar new places quite like Jan St. Werner has been doing with his Fiepblatter series.  Some installments have certainly been better than others, yet St. Werner always brings a unique blend of bold conceptual vision, rigorous craftsmanship, and playful experimentation.  With Spectric Acid, he continues that noble trend in supremely vibrant fashion, taking inspiration from ceremonial West African rhythms to weave a dense tapestry of dynamic shifting pulses, dense synth buzz, and squalls of electronic chaos.  At its best, it sounds like a particularly visceral blend of exquisite sound art and an out-of-control train.

Few artists continually push their art into strange and unfamiliar new places quite like Jan St. Werner has been doing with his Fiepblatter series.  Some installments have certainly been better than others, yet St. Werner always brings a unique blend of bold conceptual vision, rigorous craftsmanship, and playful experimentation.  With Spectric Acid, he continues that noble trend in supremely vibrant fashion, taking inspiration from ceremonial West African rhythms to weave a dense tapestry of dynamic shifting pulses, dense synth buzz, and squalls of electronic chaos.  At its best, it sounds like a particularly visceral blend of exquisite sound art and an out-of-control train.

St. Werner opens Spectric Acid with quite a powerful statement of intent, as "Acideous Welsh" is a sputtering eruption of squelching electronic chaos over a broken, yet pummeling groove…of sorts.  The "groove" never quite feels like anything other than a percussive attack though, despite the occasional appearance of a densely buzzing bass throb that ultimately proves to be just a tease.  More than anything, "Acideous Welsh" sounds like a ferocious, futuristic laser battle experienced from a trench near some of the heaviest artillery.  Oddly, it does not evolve much from its explosive beginning, as St. Werner seems more than happy to just unleash a strafing sci-fi cacophony.  The intensity remains roughly the same with the following "Victorian Trajectory," which marries slowly flanging, massive slabs of synth drones with a wild percussion foundation that sounds like excerpts from a free-jazz drum solo that are constantly shifting in tempo and fading in and out of focus.  It is probably the most perfect distillation of what St. Werner is doing on this album, as the spacey drone thrum provides an immersive and relatively consistent headspace to get sucked into, giving me enough of a "song" to grasp onto as he unleashes skittering and clattering percussive mayhem all around me.  That is, more or less, the essential difference between Spectric Acid's best pieces and the rest of the album: a virtuosic show of force (albeit an inventively polyrhythic one) only makes a big impact once–there needs to be something deeper happening for it to hold up with repeat listens.

Fortunately, St.  Werner manages to hit the mark quite convincingly a few more times over the course of Spectric Acid.  My favorite piece is "Insuline" which sounds like the smoking wreckage of a great dub techno cut that somehow overheated and went haywire.  There are ghosts of chords and melodies floating above the ruins, but the foreground is all stuttering, overloaded bass throbs; squiggling and gnarled electronics; erratic kick drum stomps; and a viscerally unpleasant escalating whine.  It feels a lot like having a complete psychotic breakdown at a rave while pointedly ignoring a shrieking teapot, which is not a vibe that a hell of a lot of other artists would shoot for.  St. Werner perversely reprises that "teapot" aesthetic again with the shorter "Solo Winslet," which feels like an even more sickly and jabbering version of the same material (perhaps the unexpected final death throes of its predecessor).  Elsewhere, "Gourd Skin Particles" takes a comparatively understated approach, taking the howling and stuttering electronic maelstrom down to a gently simmer, but compensating with an inventive textural leap into something that sounds like digitized and burbling viscous liquids.  For his final piece, "Bata Punch Bird," St. Werner creates something that sounds like the unholy coupling of a woodpecker and a sentient, yet mentally unstable modular synth.  That is certainly an unnerving and perplexing final act for an unnerving and perplexing album, but St. Werner cannot resist throwing in one last contrarian and wrong-footing surprise in the final seconds, completely abandoning all electronics for a cathartic flurry of trashcan lid percussion.

Discussing my perceived faults with Spectric Acid is something of a futile endeavor, as Jan St. Werner seems like an prodigiously talented iconoclast who does exactly what he wants to do and does it convincingly: there are certainly elements that I like and do not like, but I never feel like St. Werner made a misstep or fell short of hitting the mark he targeted.  Basically, I just need to accept that St. Werner is a deeply idiosyncratic artist who gleefully plunges into whatever rabbit hole fascinates him the most at a given time with no concern about whether there will be an audience for it.  Also, this is art, not entertainment.  As a fan of challenging music, I am delighted that he keeps finding new vistas to explore.  I would definitely like Spectric Acid more if St. Werner had used his explosively blurting electronics and unpredictably rhythmic experiments as a jumping-off point for deeper compositions with a bit more of a melodic or harmonic component, but that probably seemed like unnecessary window dressing to him: the experiments themselves are the point, not whether or not he can make them pretty.  As such, Spectric Acid is a fundamentally difficult and abstract album, but it compensates quite a bit through its bold vision, raw power, and sheer unpredictability.  More importantly, St. Werner is boldly and single-mindedly straining to redefine what is possible and push electronic music into uncharted new territory.  Other people can popularize these ideas when they catch up–for now, St. Werner is the one doing all the heavy lifting.  While it is a bit too prickly and obsessive to be one of my personal favorite albums of the year, it is very easy to imagine Spectric Acid being a significant influence upon some of my future favorites.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

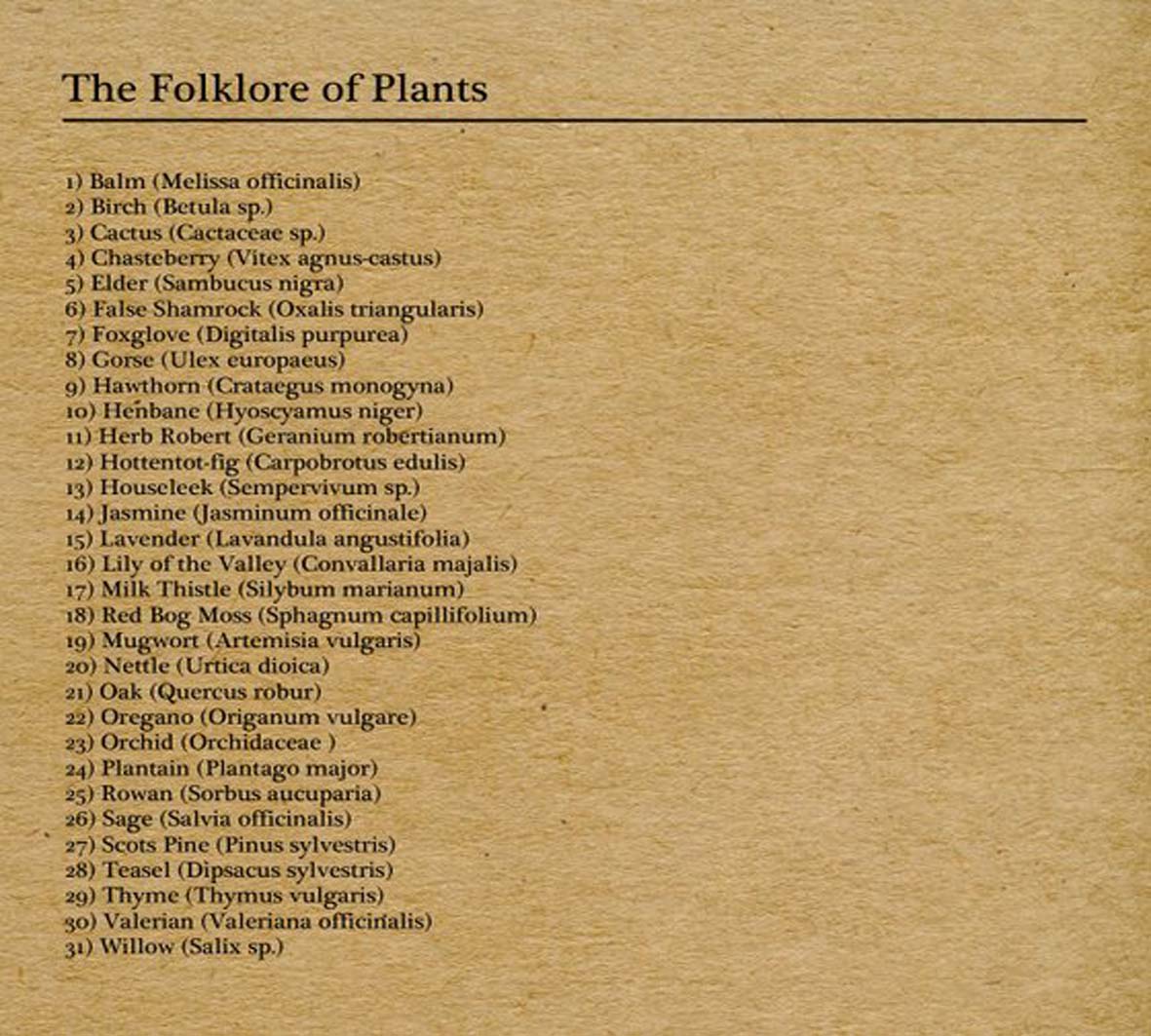

This latest Folklore Tapes collection is a perfect illustration of why they are possibly the most unique and fascinating label around, assembling 31 different artists to create free-form sound art based upon their research into a specific plant. I certainly like the concept and appreciate the depth and breadth of their commitment to it (there is accompanying literature, a film, and a pack of seeds), yet none of that would matter all that much if the music was underwhelming. As it happens, the music is absolutely wonderful, as the many brief and varied vignettes form a wonderfully surreal and kaleidoscopic whole. A few of the participants were familiar to me beforehand (Dean McPhee, Bridgett Hayden), but most were not and nearly every single one brings something delightfully bizarre, hallucinatory, or enigmatically esoteric to the table.

This latest Folklore Tapes collection is a perfect illustration of why they are possibly the most unique and fascinating label around, assembling 31 different artists to create free-form sound art based upon their research into a specific plant. I certainly like the concept and appreciate the depth and breadth of their commitment to it (there is accompanying literature, a film, and a pack of seeds), yet none of that would matter all that much if the music was underwhelming. As it happens, the music is absolutely wonderful, as the many brief and varied vignettes form a wonderfully surreal and kaleidoscopic whole. A few of the participants were familiar to me beforehand (Dean McPhee, Bridgett Hayden), but most were not and nearly every single one brings something delightfully bizarre, hallucinatory, or enigmatically esoteric to the table.

It is quite hard to conclusively pin down "the Folklore Tapes aesthetic," as it can shift significantly from release to release, depending on both the theme and the participants involved.However, there are definitely several fertile strains of subterranean music that tend to frequently find a home on the label.Obviously, any label devoted to folklore is undoubtedly going to have some folk/traditional music, but even that is rarely presented in its expected form, instead embracing the magical unreality of a folktale.The sole exception to that rule here is Jennifer Reid’s a capella performance of "Let No Man Steal Your Thyme."More typically, Folklore artists opt for a more illusory vision of "traditional music" that feels ancient and ritualistic, such as the haunting drones and rattling strings of James Green's "False Shamrock."The other threads, of course, are considerably more outré.Naturally, no UK folklore-themed collection would be complete without a bevy of half-kooky/half-creepy retro "library music" artists, best represented here by Belbury Poly's gleefully blooping "Hawthorn" (the unexpected jaw harp is an especially nice touch).The dominant aesthetic on this particular release, however, is collage.That form lends itself quite nicely to the unpredictable and hallucinatory atmosphere of the album, also lending itself quite nicely to the occasional spoken word performances.That said, there is also another harder-to-define category, which is can best be described as "batshit crazy."In that regard, Hugh Metcalf steals the show, muttering and jabbering about jasmine over some clattering that sounds like a bucket and some random kitchenware.Also, his piece definitely sounds like it was "composed" on the spot and recorded on a boombox.While definitely a piss-take, it is quite an endearing one and does not feel out of place amongst the other efforts.Part of the beauty of the collection is that everyone is essentially on the same footing: an accomplished musician, a lunatic in his kitchen, and an herbalist all have roughly a minute to make an impact however they can, which brings out a lot of creativity and ingenuity.The scholar and fool each have an important part to play in this strange tableau, as do children and animals.

While there are many individual pieces that stand out as particularly inspired, the real magic lies in how the pieces flow together as an absorbing and deliciously phantasmagoric whole.An album filled completely with people reciting recipes or describing the properties of nettles probably would not be very good, but in the context of The Folklore of Plants' deeply lysergic flow, those moments appear as beautifully disorienting oases, like flicking snatches of actual memories creeping into a singularly bizarre and shifting dream.Of course, much credit must go to the handful of artists that devoted themselves wholeheartedly to making this collection such a mind-warping plunge into a half-sinister/half-blissful funhouse of unreality in the first place.My favorite is probably the duo of Carl Turney and Brian Campbell, who celebrate the virtues of robert geranium with a deranged fantasia of pounding drums, odd beeps, chopped and distorted speech, and a child listing the herb’s various other pseudonyms ("death comes quickly" being one of them).Elsewhere, Folklore Tapes mainstay Ian Humberstone salutes red bog moss with something that sounds like a crackling field recording of a séance with a supernatural cat.Magpahi’' ode to mugwort is similarly haunted, as Alison Cooper quietly sings a melancholy melody over a sickly and brooding bed of thick analog synth tones.Less unnerving, but similarly striking, is Mary Stark's "Lavender," in which a pretty Siren-esque voice floats through a shifting collage of nature sounds, city noises, and random radio transmissions.David Chatton Barker’s "Elder" is yet another sublime plunge into the unearthly, weaving together uncomfortably harmonizing drones, strangled feedback, and a host of grinding and crackling textures.

My sole critique is simply that extreme brevity suits some artists better than others, so an artist like Dean McPhee (who specializes in slowly shifting extended pieces) is not able to play to his strengths.Necessity is the mother of invention, of course, but there are certainly some pieces that feel like mere glimpses of something more substantial rather than a self-contained and discrete soundworld.Lamenting how an individual piece in a perfect mosaic could have stood out more effectively completely misses the point though: Folklore Tapes have crafted quite a singular labor of love here and it is an absolutely beautiful thing to behold.As a compilation, The Folklore of Plants is certainly a deeply inspired collection of divergent and compelling artists, but it also offers something far more transcendent than that, stripping away all the noise and empty distraction of the modern world to reveal a window into something considerably more timeless, haunting, and ineffable.

- James Green, "False Shamrock (Oxalis triangularis)"

- Mary Stark, "Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia)"

- Magpahi, "Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris)"

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

While I suspect Thomas Meluch will always be best known for his more traditional albums, he has quietly become one of North America’s most consistently compelling ambient/drone artists over the last few years.  On this, his first full-length for Portland’s Beacon Sound, Meluch returns to roughly the same territory that he explored on 2015’s gorgeous Sonnet and his self-released Stanza series: lush, slow-moving, and gently undulating drones drifting through a haze of tape hiss.  There are some intriguing small-scale transformations to be found, however, as Meluch's focus has subtly shifted away from structure and melody into an increasing deep fascination with the textural possibilities of weathered and distressed tapes.

The seven songs of Lignin Poise are all very much of piece, essentially unfolding as a series of subtly different variations on single strong vision.  The opening "Hawk Moth Mirage" is probably the strongest articulation of that vision though, feeling like a massive cloud expanding and billowing outward in slow-motion, yet diffuse enough to allow some dazzling and ephemeral flickers of sun to shine though.  I have probably used similar language to describe similarly hazy yet dynamic drone albums, but few artists can make it feel as effortless and organic as Benoit Pioulard.  "Hawk Moth Mirage" feels like a vaporous living entity that Meluch simply conjured into being.  That, more than anything, is the genius of Lignin Poise: a master illusionist has artfully blurred and obfuscated his compositions so skillfully that they feel more like a natural, elemental phenomenon than a painstakingly layered and produced collage of synth tones.  It essentially feels like Meluch astrally traveled into a radiant, rapturous, and light-filled alternate dimension, made a bunch of stunning field recordings, then accidentally left all the tapes in his yard for a few days: glimpses of absolutely sublime beauty abound, but it feels like the struggling tape deck is having quite a hard time getting the speed the just right and the signal to noise ratio errs heavily towards the latter.

While that general description could almost be cut-and-pasted to apply to any song on Lignin Poise, there are a handful of stronger pieces that Meluch allows a bit more time to unfold.  "Same Time Next Year," for example, is essentially a reprise of "Hawk Moth Mirage" in almost every respect, but with the see-sawing pointillist synth motif replaced by a glacially unfolding melody that swells out of the underlying chords only to quickly dissolve.  It is quite lovely and understated, unfolding like a warm and bittersweet dream.  As usual, Meluch’s genius for texture and detail does a lot of the heavy lifting, as the shivering, decaying notes appealingly fall somewhere between "spectral" and "sizzling."  The atypically brief "Vesperal" is another gem, largely eschewing instrumentation in favor of layered, blurry voices.  It sounds like a warped VHS tape of an angelic choir, yet gradually becomes something a bit darker and more mysterious, as the voices sound increasingly dissociated from one another and the surrounding grit takes on an almost grinding texture.  Similarly brief, "On Form" is another divergent experiment, gradually building up to a muted crescendo that sounds like churning, overlapping loops of string ensembles emerging from a thick fog.  Elsewhere, Meluch returns once more to his "hissing dream cloud" comfort zone with the album’s closing pieces. "Rook" diverges a bit from the formula with the addition of a wobbly repeating melodic line, however.  In fact, it sounds weirdly like an abstract, hallucinatory, and monomaniacally obsessive cover of Julee Cruise's "Falling" (better known as the original Twin Peaks’ theme) that just endlessly fixates on the ascending melody that leads into the chorus.  The 10-minute title piece heads in the opposite direction though, blurring its underlying structure and its buried melodies so effectively that it just feels like a warmly enveloping multi-colored fog rolling across a field or floating upward from a twilit harbor.

While a few of the other pieces sometimes feel a bit like Meluch is treading water, it is extremely hard to find fault with Lignin Poise at all.  Within the realm of ambient music, Benoit Pioulard shares a lot in common with Andrew Chalk: both artists make extremely lovely, instantly recognizable music and rarely release a weak album.  It would certainly be cool if each new release marked an unambiguous leap forward, but art does not work like that.  Instead, Lignin Poise is kind of a lateral evolution, noticeably tweaking some elements, but not so much that a casual listener would find it conspicuously different from, say, Stanza.  As such, Lignin Poise is significant mostly for just being another great Benoit Pioulard album that deepens an already wonderful body of work.  Admittedly, this is probably the most uniformly strong of Meluch’s ambient releases to date, but Sonnet and Stanza both pack enough moments of transcendent, gently hallucinatory heaven to make choosing a favorite an impossible and unnecessary endeavor.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Ben Frost continues to mine the rich vein of recordings he made with Steve Albini with this full-length follow-up to this year's excellent Threshold of Faith EP. Naturally, The Centre Cannot Hold is a similarly face-melting eruption of ambient drone beefed up to snarling, brutal immensity, yet it feels a bit anticlimactic and redundant after the EP, as three songs are repeated (although usually in different versions) and one piece clocks in at a mere 13 seconds. A few of the totally new songs are quite good, however, and Frost allows himself to indulge and experiment a bit more with structure and melody than he did with the more punchy and concise predecessor. I personally prefer the punchy and concise approach in Frost's case, but the less essential and somewhat over-extended Centre could have been a similarly strong EP if it had been distilled to just its high points. There is some prime Frost to be found here, even if the presentation is less than ideal.

Ben Frost continues to mine the rich vein of recordings he made with Steve Albini with this full-length follow-up to this year's excellent Threshold of Faith EP. Naturally, The Centre Cannot Hold is a similarly face-melting eruption of ambient drone beefed up to snarling, brutal immensity, yet it feels a bit anticlimactic and redundant after the EP, as three songs are repeated (although usually in different versions) and one piece clocks in at a mere 13 seconds. A few of the totally new songs are quite good, however, and Frost allows himself to indulge and experiment a bit more with structure and melody than he did with the more punchy and concise predecessor. I personally prefer the punchy and concise approach in Frost's case, but the less essential and somewhat over-extended Centre could have been a similarly strong EP if it had been distilled to just its high points. There is some prime Frost to be found here, even if the presentation is less than ideal.

As far as opening statements go, it is pretty hard to top the shuddering, woofer-straining sizzle of "Theshold of Faith," which appears to be included here in the exact same form as it did on the EP.I guess that means that the EP has been retroactively downgraded to a mere hit single that preceded the album.I can certainly see why Frost would want to reprise it, as it is unquestionably the crown jewel of the Albini sessions (so far, anyway).The following "A Sharp Blow in Passing" starts off quite promisingly too, unfolding a lovely progression of ghostly chords over a stumbling, understated beat and washes of hiss.An odd thing happens around the halfway point though: the song dissolves, then reappears as a twinkling crescendo of majestic goth-tinged synth melody…then abruptly shifts gears again into something that feels like a melancholy harpsichord outro (albeit one filtered through Frost’s grainy, distorted sensibility).That chain of events illustrates some recurring frustrations that I have with Frost's work: he is not nearly as unerring in his judgment as a composer as he is as a producer.Also, he has an exasperating love of grand gestures.Given his tendency towards extreme volume, extreme textures, extreme saturation, and extreme dynamics, I wish he would shy away adding extreme melodic crescendos to the heap, as it is simply too much and tips the whole thing into "bombast" territory."Trauma Theory" initially returns to Frost’s comfort zone of shuddering, impossibly dense drone-quake, but again gives way to a prominent melody at the midway point.It works a lot better this time though, as it is quickly overpowered by the usual roar and later warps into something that sounds like a hallucinatory calliope melody.It ends extremely abruptly, for some reason, but is otherwise a very strong piece that pushes Frost’s aesthetic a bit further than his usual constraints with no ill results.

"Eurydice's Heel" is another carryover of sorts from Threshold, but this time it is a longer and better version with a nice coda of shuddering pulses.This is where the album starts to truly catch fire for me, though the massive and grandiose "Ionia" is a bit too over the top for my taste.Elsewhere, however, "Meg Ryan Eyez" is a wonderful piece of throbbing, understated drone with bittersweet melody bubbling underneath, as is "Healthcare" (albeit with quite a bit more sizzle).Naturally, "All That You Love Will Be Eviscerated" makes a fresh appearance as well, but that was unavoidable (it was the source material for two remixes on Threshold).I am not sure I prefer this "original" version to Albini's remix, but it does boasts a wonderful and massive-sounding insectoid shudder at one point, thus justifying its return.Frost saves some of his best work for last though, as the closing "Entropy in Blue" sounds like the seismic pulse of a immense machine strafed by squalls of howling noise.Then the bottom drops out to leave only a bass line in a haze of cracking static and ghostly synth swells.That would have been a cool way to fade out, but Frost is Frost, so there is a crushing, stuttering resurgence instead.In the final moments, it feels like a great dub techno piece inflated to grotesque, speaker-shredding proportions.And then...everything disappears to leave only the sounds of waves washing up on a beach.I suppose that is truly the only appropriate way to end an album this apocalyptic.

While I did not like Centre as much as Threshold, I readily concede that Frost is still operating on a plane all his own as far as production and sound design are concerned.No one else makes albums this explosive, so my only real critique is regarding how he chooses to direct that awesome firepower.I have no doubt that he is always in complete control, but he does seem a bit conflicted and eager to try out different ways to escape his self-imposed stylistic constraints this time around.In one sense, he has already found a way out, as he has expanded into film and theater soundtracks, video game music, and even directing theater.With Centre, those extracurricular activities bleed into Frost’s own art a bit and the various facets of his work do not always coexist easily (the center cannot hold, one might say).For example, in the context of Centre, the crescendo of "A Sharp Blow in Passing" feels jarringly heavy-handed, but it would be perfectly at home soundtracking a major set piece in something like Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight trilogy: fine ideas, fine execution, but not the optimal place.Of course, since I generally do not enjoy listening to decontextualized soundtracks, that may very well be only my problem.There is enough of gulf between the "drone" and the "soundtrack" pieces to give the album kind of an uneven feel and rhythm though.As a result, this seems like the kind of album where everyone will be able to find at least one song that floors them, but few will love everything.I guess that makes it an ideal introduction for new fans, but it dilutes the power of Threshold too much to stand as one of Frost's best works for me.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Burn is superior in every way to Coleclough's other collaboration from 2008. Andrew Liles' sometimes campy, often spooky penchant for drafting other-worldly drones pairs perfectly with Jonathan's texture-rich audio and their flirtation with musique concrète is both entrancing and fun. With some of the samples apparently being drawn from Coleclough and Liles' 2008 Brainwaves set, Burn has the added bonus of featuring sounds from one of the most entertaining experimental shows I have ever seen.

Burn is superior in every way to Coleclough's other collaboration from 2008. Andrew Liles' sometimes campy, often spooky penchant for drafting other-worldly drones pairs perfectly with Jonathan's texture-rich audio and their flirtation with musique concrète is both entrancing and fun. With some of the samples apparently being drawn from Coleclough and Liles' 2008 Brainwaves set, Burn has the added bonus of featuring sounds from one of the most entertaining experimental shows I have ever seen.

Coleclough's performance at Brainwaves 2008 sticks out in my mind more than almost any other show from that year. In fact, his use of the now infamous "torch pen" is one of the most ingenious and entertaining things I've ever seen from any performer, avant-garde or otherwise. The apparatus was simple: a couple of contact mics were affixed to a plate of glass, which was suspended from a coat hanger. With Liles controlling sound and generating waves of drone, Coleclough proceeded to take a small blow-torch pen to the glass, creating cracks that were then picked up by the mics and transformed into crystalline shards of noise. It was a transfixing and beautiful thing to see and hear, and it made musique concrète more immediate and fun for me than it had ever been before. Whether or not someone was there to witness that show might affect how much they enjoy certain parts of Burn, but this album stands on its own for many other reasons. Jonathan's clever use of fire, glass, and microphones only shows up on one song ("Blackburn") and it sounds excellent even without the opportunity to watch it happen live. And Liles' input shouldn't go ignored. His signature is pretty obvious through the record, whether he's editing or inserting some ghostly audio into the mix. If it weren't for his subtle hand, Burn would be a flatter and far less engaging disc.

The album gets off to a slow start, though, with "Sunburn" dragging a little bit before "Blackburn" kicks the record into high gear. Like Bad Light, Burn features a good deal of unprocessed audio. But, it is done to much better effect this time around, in part because Liles provides an anchor for Coleclough's wandering. Bells, chimes, pianos, strings, guitar, prepared piano, and other sundry instruments all show up on various songs, but this time they're integrated into the flow of sound more completely. In fact, "Heartburn" features a brief, but powerful guitar interlude that melts perfectly into the surrounding boil of clunking metal and detuned violins. This success probably has a lot to do with Liles' penchant for combining and arranging odd sounds: he finds absolutely no difficulty in blending toys, electronic gizmos, seriously demented noise, and a good bit of humor into his music. Coleclough's expanded musical palette obviously benefits from this ability. It keeps the record from being too haphazard and it lends a lot of diversity to a kind of music that can become stale and uninteresting pretty easily. The length of each track on Burn contributes to its enjoy-ability, too: only two songs exceed the 12-minute mark, and only one ventures off into 20-minute territory. By keeping things brief in some places, Coleclough and Liles make Burn sharper and harder-hitting, which means a lot for a record that features three and four-minute fade-ins, lots of slowly developing themes, and other sonic minutiae.

Fans looking for a document of the Coleclough and Liles Braiwaves performance will be happy to have Burn, but the album offers up a lot more than memories of their live collaboration. Every song is like an extention of that performance, each of which borrows from and expands upon the original conceit. With the added benefit of some studio trickery and a little refinement, their combined effort sounds even better.

samples:

Read More