- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

In 1969, Mississippi Fred McDowell plugged in an electric guitar, and like Bob Dylan just a few years earlier, alienated many purists who could not fathom such radical change. So as not to encourage any ambiguity or doubt, McDowell's first electric record was titled I Do Not Play No Rock 'n' Roll. Whether or not Jack Rose is trying to cure ambiguities of his own with this record is unclear, but it is obvious that he's ready to move into new territory.

In 1969, Mississippi Fred McDowell plugged in an electric guitar, and like Bob Dylan just a few years earlier, alienated many purists who could not fathom such radical change. So as not to encourage any ambiguity or doubt, McDowell's first electric record was titled I Do Not Play No Rock 'n' Roll. Whether or not Jack Rose is trying to cure ambiguities of his own with this record is unclear, but it is obvious that he's ready to move into new territory.Classifying Rose as a pure revivalist has never made much sense, especially considering the scope of his career. Pelt, for instance, was too extravagant and free-spirited to be pigeonholed and his solo output is highly varied despite the fact that John Fahey is the only name I hear associated with him. He is indebted to Leo Kottke and Robbie Basho as much as he is to John Fahey. Perhaps to the untrained ear all these influences will sound similar, but ask any guitarist or pull up any Google search on the topic and you'll get a taste of Rose's diversity. His music exists somewhere between the epic scope of Indian-influenced instrumental music and the roots music of American blues and folk. He is equally cosmic and terrestrial in all that he does and tends to shy away from extremes. It is for this reason that his Three Lobed release sticks out as an oddity. Compiled from live performances in Chicago, Amsterdam, and Pennsylvania, I Do Play Rock and Roll witnesses Rose moving away from his ragtime and blues-inspired mode in order to re-encounter the the hallucinatory and hypnotic power of his early solo output. Truth be told, such experimentation and diversity was present on Dr. Ragtime and His Pals and Kensington Blues, but on I Do Play... the rolling and ethereal qualities of which Rose is capable dominate the comparatively relaxed and familiar sounds of American folk music with which he is so often associated.

To this extent it is difficult to understand why Rose thinks this album has anything to do with rock and roll. His phrasing, tone, and predeliction for intricacy all betray any ties to rock music, not to mention obvious things like the lack of lyrics and regular rhythms. Rose's playing sort of rambles along: it sometimes mumbles and sometimes explodes with clarity and memorable melodies, but it never dissolves into pure improvisation. On "Calais to Dover," which originally appeared on Kensington Blues in an abbreviated form, Rose often falls into introspective movements where quickly fingered rhythms acquire a wave-like quality, rolling as they do in splashes of force and emphasis. His focus is mostly rhythmic throughout the piece and though clear melodies exist, rhythm nevertheless asserts itself as the primary element, forcing the ear to listen for metered patterns instead of melodic or harmonic ones. This song is far and away the best piece on the record and it is arguably its center. "Cathedral et Chartres," also from Kensington Blues, isn't half as long as "Calais to Dover" and runs only a fraction of the time that "Sundogs" does. It is more pastoral and gentle than either tune and, in some ways, occupies its place on the record only to provide relief between the two extremes found on the other songs.

If this album's title is to have any meaning whatsoever, it is to be found somewhere on "Sundogs," the album's final song. It's a 20-plus minute, high-pitched drone apparently extracted from one or more of Rose's guitars. It is cold, steely, and a little frightening with little variation. It provides practically no insight into what Rose might be doing and is generally mystifying from start to finish. There are audible coughs on the recording and it isn't difficult to imagine a few confused and perturbed audience members shuffling about, wondering what it is that Rose is trying to accomplish. In fact, I feel this way listening to the recording. It serves up dark introspection and creeping dread in massive doses, but is the complete antithesis of everything else on the record. Sounding like the complete obliteration of everything Rose has done in the last few years, "Sundogs" is both enjoyable and a little frustrating. Whether or not Rose is signalling a new beginning or simply throwing his listeners something different is up for debate. One thing is clear: if Jack Rose thinks he's playing rock and roll, it's because he's thinking about McDowell and Dylan and what happened when they decided to plug in and change their approach a little.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Fabrique documents many of the performers included in Lawrence English's long-running experimental music series. The focus is largely on laptop-based ambient glitchery, but several artists contribute strong-based tracks that depart from this aesthetic (usually by incorporating human or organic elements). Notably, the lesser-known artists (such as Tujiko Noriko) often steal the show from more established folks like Scanner or KK Null.

Fabrique documents many of the performers included in Lawrence English's long-running experimental music series. The focus is largely on laptop-based ambient glitchery, but several artists contribute strong-based tracks that depart from this aesthetic (usually by incorporating human or organic elements). Notably, the lesser-known artists (such as Tujiko Noriko) often steal the show from more established folks like Scanner or KK Null.

Lawrence English curated the Fabrique series for eight years and organized 40 events, luring avant-garde artists from all over the world to his oft-neglected home continent of Australia. This compilation is not a comprehensive retrospective, but merely a sampler of some of the more intriguing performers’ works. Only a few of the tracks are actually live recordings from Fabrique events (Scanner and Keith Fullerton Whitman), but the rest of the tracks are exclusive to this compilation.

The first two tracks (by David Grubbs and Chris Abrahams) are enjoyable enough, but nothing held my attention until Fourcolor's "Familiar," a warm and languid haze of ambient bliss. I am sure the formless floating and wordless, breathy vocals would be cloying for the duration of an entire album, but as a single track it provided a refreshing respite from the stark electronics surrounding it. Janek Schaefer's "Fields of the Missed" also stands out from the rest of the album, with its exuberant menagerie of manipulated animal sounds hovering above a warm, wavering drone. It eventually drops most of the field-recording component and morphs into a thick, consonant swell, which is pleasant, but not nearly as odd and attention-grabbing as the first half.

The album closes with Tujiko Noriko's "Magic," a compelling foray into odd, lurching, somnambulant near-pop that approximates Múm or Björk. It is probably the most immediately gratifying track on the album, but there are several other intriguing pieces on the album; many of which are by Australians that I was not previously familiar with (I was particularly struck by Leighton Craig’s somewhat childlike and elegiac organ piece “San Souci”). English clearly has excellent taste and a comprehensive knowledge of the international experimental music scene, which makes him the perfect curator for such a series. Well, almost. The catch is that his taste is very specific: artists that sound similar to Lawrence English (drone-y and somewhat austere). Consequently, there is a distinct lack of percussion, harshness, or recognizably organic instrumentation represented. While it's not necessarily a bad focus for an experimental music concert series, it's not necessarily a recipe for a varied and unique compilation album either.

Fabrique is certainly a pleasantly diverting listen, but a bit too subdued and homogenous to make a large impression on me. Nevertheless, it provides an excellent window into the Australian electronic music scene, as well as some decent unreleased material from more internationally known artists (the artists from the Room40 roster submit particularly strong material, but 12k makes an impressive showing too). Of course, I’m a little disappointed that English did not include one of his own tracks, but I suppose his modesty is commendable. Regardless of its degree of success as an album, Fabrique provides ample evidence that Fabrique was an excellent and inspired series.

Samples:

- Fourcolor - Familiar

- Janek Schaefer - Fields Of The Missed

- Tujiko Noriko - Magic

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Soundtrack music has always held its own odd space in the music world. Living in constant relation to the images it is meant to accompany, soundtrack music can (and has) made movies as well as destroyed them, as any Ennio Morricone fan can attest to. Yet the best soundtrack music has always been able to positively shape a film while still standing on its own as strictly a musical work removed from its image-based companion. It is, it seems, this trait alone that separates the comparatively schlocky Hollywood mood-manipulations of a John Williams score from the intrinsic depth and subtlety of form found in an Anton Karas, Carl Stalling, Nino Rota, or Bernard Hermann piece. JG Thirlwell (most know him as the man behind Foetus, Wiseblood, Steroid Maximus, etc.) proves himself more than an adept contributor to the genre.

Soundtrack music has always held its own odd space in the music world. Living in constant relation to the images it is meant to accompany, soundtrack music can (and has) made movies as well as destroyed them, as any Ennio Morricone fan can attest to. Yet the best soundtrack music has always been able to positively shape a film while still standing on its own as strictly a musical work removed from its image-based companion. It is, it seems, this trait alone that separates the comparatively schlocky Hollywood mood-manipulations of a John Williams score from the intrinsic depth and subtlety of form found in an Anton Karas, Carl Stalling, Nino Rota, or Bernard Hermann piece. JG Thirlwell (most know him as the man behind Foetus, Wiseblood, Steroid Maximus, etc.) proves himself more than an adept contributor to the genre.

Part of the difficulty inherent in the form is, of course, working within the relatively narrow confines afforded by accompaniment of an image. Not only must a work set the mood of the image, it also (if it's good, anyway) must remark on and strengthen the pictorial element. If it's truly great it can do all this while still maintaining its musical dignity. Take, for example, Stalling's incredible arrangement of Michael Maltese's writing in Chuck Jones' "Rabbit of Seville." Working within Rossini's "Barber of Seville" melodies Bugs Bunny, beckoning Elmer Fudd to get his haircut, punctuates along to Rossini's famous melodic line: "Don't look so perplexed / Why must you be vexed? / Can't you see you're next? / Yes, you're next. / You're so next." Even given the restraints, Stalling and co. manage to sum up Bugs' entire modus operandi in three simple syllables that say more than most dissertations could: "You're so next."

While Thirlwell does not have quite the options presented to Stalling in terms of character development (there is no lyrical content on the album) he still manages to say plenty. Thirlwell's score, like the cartoon it soundtracks, is exciting to its core, bouncing ideas around one another with hectic abandon that simultaneously pays loving homage to and caricatures the work of the greats. The opening "Brock Graveside" is as honest a Morricone rip as you could ask for, complete with lone whistling and muted trumpet. Following it up with the spy-thriller antics of "Tuff" gets the disc rolling quickly, immersing you in its over-the-top production and go-for-broke approach.

What makes the album remarkable however isn't that Thirlwell pulls out all the stops, but that he does so in such a focused and articulate manner. More than any one track being a highlight, the entire work flows smoothly from traditional soundtrack styles through to psychotic electro-funk without ever losing sight of its identity.

What's further, it's masterfully produced and every sound, whether it be the consistently pummeling drum work or the brass band backing, is treated with precise and orchestrated detail. Clearly no band effort, each track presents new sounds, new approaches, and new modes of the same singular sound that Thirlwell's mind hatches throughout. "Mississippi Noir" is, as it sounds, an odd and lilting banjo number whose sloppy, backroom bar piano only solidifies the unavoidable images of some bayou swamp. While the trance of a trumpet may be as rough and guttural as one would hope for from this far south of the Mason-Dixon, the entrance of deep bass drums and a psychedelically inclined chorus of chanting vocals gives it another dimension which inevitably strengthens its ties to the cartoon medium.

By the end Thirlwell's controlled production, fun arrangements and near limitless scope will have anyone firmly in its grasp. It is—and I use this term cautiously—a brilliant work that could well place Thirlwell as the next in line to the pantheon of soundtracking greats. Stalling, Morricone and now, Thirlwell, the cartoon soundtracker for the 21st century. As Bugs might say, "he's so next."

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Montreal's trio of talented multi-instrumentalists hit pay dirt on this album. Revolving around a core of keyboards, drums and French horn, the group has carved out a pleasant niche for themselves inside the well traveled corridors of cinematic psychedelia, employing numerous other devices and useful effects along the way.

Montreal's trio of talented multi-instrumentalists hit pay dirt on this album. Revolving around a core of keyboards, drums and French horn, the group has carved out a pleasant niche for themselves inside the well traveled corridors of cinematic psychedelia, employing numerous other devices and useful effects along the way.

Most albums don’t begin with an “interlude” but this one does, doing the same job as an intro, but better, like I am already keyed in to the action of the plot. It could have been written after the title track, which follows the opener, where the melodic themes hinted at in the “interlude” are stretched out and more fully developed. Everything here is arranged in well fit layers, like an actor in a period costume, whom Torngat might well be providing the soundtrack for. A kaleidoscope of timbres illuminates the hierarchies of the harmonic spectrum, all glowing, washed in the thick espresso sludge of reverb and carefully attenuated distortion that coats all the remaining songs.

Whereas the edges come off rough hewn from the fuzzy swamp gas effects, shimmering melodies float gracefully rising like angels above the crinkling sheen of soft white noise. The group show themselves as being well listened in the prog rock and kraut arenas. Feedback, heavy riffing, and fluid drums (sometimes sounding like they are being played underwater), are all evident on songs like “L’Ecole Penitencier” and “Turtle Eyes & Fierce Rabbit.” “6:23 PM” shows a more subtle, ambient side: the slow but throbbing key playing on this track reminded me on every listen of the dreaminess of the classic Eno song “Spider and I.” This is in no way a disparagement of the piece, but added a weight of familiarity as well as mysteriousness. Gentle piano trickles, alongside a windy electric blur, keep it full bodied and well rounded.

The real light of the group shines through on pieces like “Afternoon Moon Pie” and “Going Whats What,” streaming, coaxed out of the curved brass that is the French horn. Whereas many bands will have garish tracks full of bombast and unnecessary pomp when they bring in a horn section, a single French horn imparts a more pure kind of regality altogether. For Torngat it has the benefit of setting them apart from the crowd.

samples:

Read More

For An Outbreak of Twangin', the follow-up to 2008's Phantom Guitars, The Bevis Frond's Nick Saloman has again assembled a couple dozen incredibly obscure and kitschy surf guitar gems. I am pleased to report that the influence of legendary paranoid reverb-monger/occultist/murderer Joe Meek looms large here.

For An Outbreak of Twangin', the follow-up to 2008's Phantom Guitars, The Bevis Frond's Nick Saloman has again assembled a couple dozen incredibly obscure and kitschy surf guitar gems. I am pleased to report that the influence of legendary paranoid reverb-monger/occultist/murderer Joe Meek looms large here.

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

For An Outbreak of Twangin', the follow-up to 2008's Phantom Guitars, The Bevis Frond's Nick Saloman has again assembled a couple dozen incredibly obscure and kitschy surf guitar gems. I am pleased to report that the influence of legendary paranoid reverb-monger/occultist/murderer Joe Meek looms large here.

For An Outbreak of Twangin', the follow-up to 2008's Phantom Guitars, The Bevis Frond's Nick Saloman has again assembled a couple dozen incredibly obscure and kitschy surf guitar gems. I am pleased to report that the influence of legendary paranoid reverb-monger/occultist/murderer Joe Meek looms large here.

Psychic Circle

Generally, the word "outbreak" is intimately intertwined with something negative (such as chlamydia), but this disc bucks that trend admirably. Most obviously, this is an extremely fun and consistently excellent album. Secondly, while most of the artists are British, there are many unexpected contributions from countries that are not traditionally associated with surf music (as well as a conspicuous absence of Americans). Finally, I have yet to be disappointed by any album that features bands dressed like vikings (the Saxons) or gladiators (Nero and The Gladiators).

The liner notes are quite entertaining and obviously required quite a bit of research on Salomon’s part. For example, several of the unknown and enigmatic bands included share names with other bands (The Boys, the Volcanos, The Rapiers, etc.), which must have been rather confusing. Also, some bands—such as Norway’s The Runestones and Ahab & The Wailers—still remain completely shrouded in mystery despite his best efforts. The fact that there is at least one man on earth tirelessly trying to unearth the history of Scandinavian surf bands makes me extremely happy. Incidentally, the band with the most bizarre story here are certainly Joe Meek protégés The Saxons, who later became The Tornadoes (because the actual Tornadoes broke up and Joe thought they were too popular to not replace). Also, their guitarist eventually wound up in an Israeli prog band.

It is hard to choose favorites, as Twangin’ is a fairly full-throttle beach blast from start to finish, but The Boys' “Polaris” is an exceedingly rocking gem in the traditional surf vein: deep, twanging guitars, twinkling piano, and a propulsive snare roll rhythm. Immediately afterwards, The Saints' “Husky Team” adheres to the same formula, but amplifies the intensity considerably with muscular stomping drums and occasional interludes of snare fills and party banter and hooting. I am always a big fan of tracks that feature sounds of people partying: I like to imagine that it means that the track was so infectious and amazing that the usually curmudgeonly engineer and bored session players had no choice but to erupt in spontaneous dancing and revelry. It would kill me to find out otherwise. Also of note, I believe "Husky Team" was recorded with Joe Meek (although Meek’s rabid passion for reverb and echo is everywhere on this album, whether he was involved or not).

“An Outbreak of Murder” by The Gordon Franks Orchestra is a bit of an aberration here, as it veers into noir-ish lounge music territory and is far more indebted to Martin Denny than The Ventures. However, several other tracks do diverge somewhat from surf into more rambunctious Duane Eddy territory (like the Ramblers' “Just for Chicks”) or betray a western or boogie-woogie influence.

Obviously, listening to 26 surf guitar instrumentals in one sitting invariably and rapidly starts to yield diminishing returns, but Saloman has done an amazing job with track selection. There are no weak or overexposed tracks on Outbreak at all; just fun, camp, and absurdity (the liner notes helpfully point out that this album is the next best thing having "a funfair in your own living room").

samples:

- The Boys - Polaris

- The Saints - Husky Team

- The Gordon Franks Orchestra - An Outbreak of Murder

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This split album between Ohio’s Emeralds and Japan’s Pain Jerk was initially made to accompany their co-headline tour of the UK but thankfully it has made its way into the wider world. Both groups have done the decent thing in including top quality tracks when any old tosh would do. On paper, the idea of pairing these artists seems bizarre and with over half an hour of bliss from Emeralds and a truck load of sonic hell from Pain Jerk, the word “split” has never felt so apt.

This split album between Ohio’s Emeralds and Japan’s Pain Jerk was initially made to accompany their co-headline tour of the UK but thankfully it has made its way into the wider world. Both groups have done the decent thing in including top quality tracks when any old tosh would do. On paper, the idea of pairing these artists seems bizarre and with over half an hour of bliss from Emeralds and a truck load of sonic hell from Pain Jerk, the word “split” has never felt so apt.

Emeralds’ recent two above ground releases, Solar Bridge and What Happened, are two of the most rewarding releases I have had the pleasure of hearing. The two albums take what Emeralds have been doing on their many, many cassette and CD-R releases and refines them into something even more magical. Arguably, “Landlocked,” from this split CD goes even further. I have said before that Emeralds sound exactly like every obscure band from '70s Germany that you have read about but never heard and the Kosmische synth jam here lives up to that statement. Yet what sets Emeralds apart from their contemporaries is not only that they are much more indebted to the sounds of Cluster and Tangerine Dream than others in the noise tape scene but also that they are seem to fight constantly against stagnation. “Landlocked” is forever shifting in tone, mood and energy; at one moment Mark Maguire’s gentle guitar shimmers in the background as the two synths swirl and sing around him and the next he is in the forefront as the machines become details. The entire piece is superb for its restraint and its hypnotic beauty.

After almost 30 minutes of this dreamlike music, Pain Jerk’s explosive “Beserker” tears through the speakers like a stab wound. Vastly unpleasant in comparison to Emeralds, this is Japanoise at its finest. Taking cues from Incapacitants’ and C.C.C.C.’s harsher moments, Pain Jerk are one of those glorious noise bands that are euphoric in their pursuit of volume. Recorded live in 2000, this piece more than lives up to its title as it rends and slashes indiscriminately over its length. Decibels of screeching feedback mix with human howls and screams, humanising the noise and making it even more punishing. By the end of the piece, bliss in oblivion is almost in sight and I am not sure if I can still hear properly. Perhaps this release should have come with earplugs...

It is depressingly rare for a split release to have much in the way of replay value, usually only one contribution is of any good and even then they tend to sink below my radar in favour of full length releases (and I must admit a lot of split releases I have bought purely out of that insatiable collector’s mentality). However, this CD goes against the grain in being utterly brilliant with both Emeralds and Pain Jerk providing sterling work that is not only substantial in terms of length but also stands proud next to their best releases.

samples:

- Emeralds - Landlocked

- Pain Jerk - Beserker

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

After three years since their demise, the final album by Khanate has finally seen the dark of night. After a lot of speculation as to whether it would actually emerge or not, my expectations were high and unfortunately they were not quite met. The improvised music was recorded during the sessions for Capture & Release with the vocals added much later. This approach has lead to a hit or miss album that is awesome when on form but a touch disappointing when not.

After three years since their demise, the final album by Khanate has finally seen the dark of night. After a lot of speculation as to whether it would actually emerge or not, my expectations were high and unfortunately they were not quite met. The improvised music was recorded during the sessions for Capture & Release with the vocals added much later. This approach has lead to a hit or miss album that is awesome when on form but a touch disappointing when not.

“Wings from Spine” has been long available on James Plotkin’s website as a work in progress and to finally hear the finished song is immensely satisfying. Alan Dubin snarls the lyrics like a feral demon. The erratic and frenetic music moves away from the slow pacing of old. This adds a ton of menace to the band’s sound but at the cost of tension. While tension is Khanate’s strongest asset, its lack is made up for by the power of “Wings from Spine.” However, the absence of any tangible dread on “Clean My Heart” makes it the weakest track on the album. It plods along aimlessly and creates no feelings of despair; it is a pale shadow when matched against Khanate at full steam.

One of the group’s biggest influences is Fushitsusha and, on “In That Corner,” this influence comes through clearly. Stephen O’Malley’s usually thick and bass heavy guitar splinters into shards of glassy notes as sharp as anything Keiji Haino can muster. Out of the four pieces on this album, “In That Corner” is the only one that truly captures the cosmic horror that is central to what made Khanate so magnetic and strangely, it is the one that sounds least like what they have done before. Hearing this brought back the same sensations as hearing those opening feedback wails on “Pieces of Quiet” on their debut album. Yet when I hear the blueprint Khanate sound of “Every God Damn Thing,” it is obvious to these ears that they called it quits at the right time. Not to badmouth this track, it is good but these guys have done this before and they have done it better. The CD version of this last track is over half an hour long (compared to just under 9 minutes on the LP) so it may be better when it has three times the space to develop but it is not out until next month so I cannot compare.

Like any tombstone, this last album serves as a reminder but not a replacement for what was. Clean Hands Go Foul does not maintain the same psychological intensity that previous Khanate albums were full of. Yes it still sounds heavy and yes all the stylistic hallmarks are present and correct but at times it feels hollow. The sense of impending doom that the group could create with their geological timing and masterful control of volume is not as apparent on Clean Hands Go Foul. Out of the four pieces, two of them are fantastic and the remaining pair do not match up to the high standards I expect. The weaker tracks could easily have come from one of the many Khanate clones that now exist and I cannot help but feel that this would have been better as a two track EP. However, I am delighted to finally be able to hear these last moments of one of my favorite bands but I do not think I'll be revisiting it as often as I have with the rest of their catalogue.

This review is from the vinyl version of the album so unfortunately no sound samples at this point in time, apologies!

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

"Free-folk" is a term that gets thrown around a lot, and to some extent it has come to represent a certain strain of quirky indie cuteness far removed from its more primitive punk precursors. Both elder statesmen of the style, Dredd Foole and Ed Yazijian have been playing together for years to little public acknowledgement. But in an increasingly open musical climate they have at last reconvened for an album of loose extrapolations within the form, proving their collective voice to be as stylistically prophetic and effective as one could hope from these two luminaries.

"Free-folk" is a term that gets thrown around a lot, and to some extent it has come to represent a certain strain of quirky indie cuteness far removed from its more primitive punk precursors. Both elder statesmen of the style, Dredd Foole and Ed Yazijian have been playing together for years to little public acknowledgement. But in an increasingly open musical climate they have at last reconvened for an album of loose extrapolations within the form, proving their collective voice to be as stylistically prophetic and effective as one could hope from these two luminaries.

Of course none of this points toward a disc like this suddenly ringing significant to the average consumer of "freak-folk." While genre stars Devendra Banhart and Joanna Newsom (especially Newsom) do indulge in their fare share of extended ruminating, nobody does it quite like Foole and Yazijian. Case in point can be found on the album opener, the lengthy "You Feel." A 20-plus minute excursion into the open structural framework surrounding Foole's spare lyrical content, the work requires little in concocting its increasingly distorted take on the quirky energy wrought by precursors such as The Fugs and Holy Modal Rounders. Delta guitar slides, plucks, and Foole's thick and emotive vocals drift endlessly into a strange space of punk attitude fed through folk styles and extended motions on variations.

"Buzzin' Fly" follows a similar format, stretching out over 15 minutes as the two seem to craft the piece on the spot. Foole's vocals are sincere to the point of intimidation, and the work is unabashedly pretty, not afraid to stick with its own guns and counting on those to keep the work interesting. It's a refreshingly unpretentious take that is neither hyper-aware of its own coolness factor nor unaware of its influences.

It is this stripped down honesty that ultimately makes the record as worthwhile as it is. Too often this sort of record either comes across as schmaltzy or self-indulgent, but the relationship between these two is long and well traveled, so it's easy for egos to be left at the door. On "Freedom" Foole sings and strums about, you guessed it, freedom, singing that, "someone said my freedom is gone." Meanwhile Yazijian's broad fiddle strokes push on the outer bounds of the form as his tones swirl in instrumental proof that such is not the case whatsoever.

"Love in the Basement" is likely the most amorphous work on the record as the two tap and twist wah'd lines around strange vocal incantations that stretch the Yardbirds classic "For Your Love" beyond recognition. Meanwhile a droney line and poetic discourse is undergone on "Charlestown Blue," further delving into the basement punk roots that are so deeply engrained in the duo's sound.

Ultimately, it's this extended sense of discourse and the raw honesty which is most effective here. These are pop tunes at heart perhaps, but they are folkier, rawer, and stranger than so many who seek to be. There is no posing necessary here though, and there is nothing more exciting than that.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

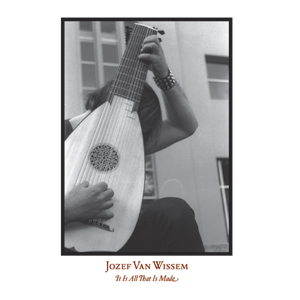

Not the most obvious instrumental choice for the modern age, the lute is far more often associated with Renaissance fairs and Dungeons & Dragons then contemporary minimalist composition. Yet that is exactly the approach that Jozef Van Wissem takes with this disc, combining seven compositions whose conceptual prowess ultimately proves tangential to Wissem's relaxed and stark approach to his instrument.

Not the most obvious instrumental choice for the modern age, the lute is far more often associated with Renaissance fairs and Dungeons & Dragons then contemporary minimalist composition. Yet that is exactly the approach that Jozef Van Wissem takes with this disc, combining seven compositions whose conceptual prowess ultimately proves tangential to Wissem's relaxed and stark approach to his instrument.

The conceptual basis of these works seems to, at least on the surface, be a major restriction on Wissem's compositional potential. While some of the works here consist of reworkings of 17th-century pieces and others are entirely Wissem's own, each work undergoes the same process by which it is played forward and then reversed. This palindromic approach essentially makes for twice the material out of half the composition, but Wissem's works are bare enough that even a reversal doesn't feel like a rehashing of stale ideas. Ultimately, it would seem that the approach is intended to infuse the pieces with a circular narrative whose form is removed from the very classical forms most often associated with Wissem's instrument.

As aforementioned, these ideas, however, are largely lost due to Wissem's compositional style: a fact that ultimately lends credibility to the lutenist's compositional talents. The disc opens with the gentle and spacious "Darkness Falls Upon The Face Of The Deep," a soft and sad progression that achieves the folky feel of a skeletal Fahey work. Each note is treated with respect, each chord used to further the emotive resonance of the piece.

Elsewhere, Wissem does busy his playing a bit more, as on the title track, whose finger-picked elegance has a descending bass line that lends a depth of emotion far more complex than the seemingly happy-go-lucky high-end. "In You Dwells The Light Which Never Sets" manages to sound almost banjo-esque as Wissem works and reworks the deceptively simple sounding melodic line, first with a pointillist approach and then with a sparer, more obtuse treatment of the material. The reversal is clearest when given stylistic markers such as these.

Either way, it is ultimately Wissem's compositions that shine through most strongly here. He is both a fantastic player and writer, and his reverence for his instrument's history—and thus its future—is commendable. Rarely is such an archaic sounding instrument used with such open and organic respect.

The closing "Sola Fide," a work commissioned by London's National Gallery, is meant as an aural depiction to "The Ambassador," a painting by Hans Holbein from 1533. The lively delicacy of the work breathes new life into a painting that is otherwise largely irrelevant to today's lifestyle, and it is this that Wissem does throughout with his own instrument. His work is vibrant and beautiful, but more importantly it meshes the old with the new, poising Wissem as, ironically, an ambassador for the future of a far underused musical tool.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Although not part of any of the various art related series on the label, this release from the duo of Antoine Chessex and Ktho Zoid mine similar territory as either the Arc or URSK series do: dark, bleak, meditative drones; and in this case sourced from electronics, guitar, and tenor sax. It does, however, lean more into the realms of noise than some of the other releases, and it is all the stronger for it.

Although not part of any of the various art related series on the label, this release from the duo of Antoine Chessex and Ktho Zoid mine similar territory as either the Arc or URSK series do: dark, bleak, meditative drones; and in this case sourced from electronics, guitar, and tenor sax. It does, however, lean more into the realms of noise than some of the other releases, and it is all the stronger for it.

The opening track "Shadows" begins the album with a roar, a harsh blast of guitar noise and overdriven low end scrape, along with a bit of punishing white noise above everything just for good measure. Through the fog of noise the occasional overt guitar tone rises to the surface, and what could be a tortured horn blast somewhere in the muck and mire. Not until around half way through the track does a layer resembling a chugging guitar riff come to the forefront, giving the bleakness a rhythmic underpinning while the noise continues to swirl up around it.

The shorter middle track, "Chystka" begins with a somewhat more conventional sound, a bit of lo-fi raw guitar noodling that sounds like a 1980s metalhead screwing around in his bedroom before everything rapidly descends into distortion hell. Everything becomes consumed by overdriven analog low end crunch, with violent noise elements cutting and out. One thing that separates this track from so many others though is a lot of subtle, sometimes imperceptible sounds scattered throughout. While the focus is clearly the fuzzed out stuff, the slightest change in volume, EQ, or possibly even speaker placement can reveal something different that was seemingly not there just a moment ago.

The longer closing "Let 100 Flowers Bloom" has a similar approach, but rather than opening with the harder stuff, it is more of a slow transition. It leads off with more open space, though an ominous hum stays looming throughout. What sounds like fragments of chimes and little twittering notes scurry about. The hum becomes entwined with a harmonium drone and stays with this atmospheric vibe for about ten minutes. Then, the noise blasts back up to the surface and devours everything, bringing the track closer and closer to what is traditionally labeled noise, even with the somewhat-less treated sax roaring up painfully.

The best part of this album is that there is a lot of subtleties scattered about that pull it away from simple noise drone and into a more nuanced work that builds in complexity the more I listened to it. Rather than just being cranked up to annoy neighbors (like many similar projects can be), there is a lot more to appreciate here rather than just the physical elements.

samples:

Read More