- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I have to admit that I have always been somewhat confounded by stated The Ghost Box aesthetic of "artists exploring the misremembered musical history of a parallel world," as I have little nostalgia for hazily remembered '60s and '70s children’s television and a limited passion for the vintage sci-fi sounds of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. In short, I had insufficient whimsy in my heart to properly appreciate anything that sounds like a retro-futurist alternate soundtrack for The Wicker Man. After fully immersing myself in this latest fairy-themed opus from label co-founder Jim Jupp, however, I am beginning to see the unique appeal of the willfully anachronistic collective. I am not sure if the changing world or my changing self ultimately led me to this point, but the idea of spending some time in a kitschy fever dream evocation of a cheaply constructed puppet world suddenly seems extremely appealing to me. Granted, The Gone Away still rubs me the wrong way during its more "vintage lounge music" moments, but it nevertheless feels both good and pure that Jupp is so single-mindedly focused on extracting genuine pathos from our weird, dated, and ostensibly ridiculous cultural memories.

I have to admit that I have always been somewhat confounded by stated The Ghost Box aesthetic of "artists exploring the misremembered musical history of a parallel world," as I have little nostalgia for hazily remembered '60s and '70s children’s television and a limited passion for the vintage sci-fi sounds of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. In short, I had insufficient whimsy in my heart to properly appreciate anything that sounds like a retro-futurist alternate soundtrack for The Wicker Man. After fully immersing myself in this latest fairy-themed opus from label co-founder Jim Jupp, however, I am beginning to see the unique appeal of the willfully anachronistic collective. I am not sure if the changing world or my changing self ultimately led me to this point, but the idea of spending some time in a kitschy fever dream evocation of a cheaply constructed puppet world suddenly seems extremely appealing to me. Granted, The Gone Away still rubs me the wrong way during its more "vintage lounge music" moments, but it nevertheless feels both good and pure that Jupp is so single-mindedly focused on extracting genuine pathos from our weird, dated, and ostensibly ridiculous cultural memories.

If I had any doubts about whether or not I was projecting my own preconceptions of this project onto The Gone Away, they were immediately erased by the kooky and hallucinatory promotional video made by Sean Reynard's alter-ego Quentin Smirhes.In fact, I may have even read too much seriousness into Jupp's intent, though the teasing ambiguity of Belbury Poly is admittedly part of the appeal: even when it seems silly, that silliness is invariably delivered with real heart and sincerity.Probably, anyway.Only Jupp himself knows for sure.In any case, The Gone Away is the project's seventh full-length, yet marks a return to Belbury Poly's roots in a way, as Jupp departs from his more collaborative recent endeavors for an entirely solo affair.The other salient detail is that the album is inspired by the older, darker side of fairy-based folklore.It would be a stretch to call The Gone Away a dark album though, as Jupp's cheery eccentricity proves to be irrepressible.A few pieces do, however, take on a more somber or shadowy tone.The biggest surprise in that regard is "Corner of the Eye," which initially sounds like a bleary homage to chamber music, but packs a wonderfully haunting and sophisticated central theme that sounds plucked from an impossibly cool scene in an imaginary espionage film.In fact, the entirety of The Gone Away feels like the soundtrack to an imaginary film, but one where the composer was a rather moody fellow with a macabre sense of humor and a propensity for disorienting shifts in tone.The overall effect is akin to watching a goofy and candy-colored stop-motion or puppet film that contains some unexpectedly poignant moments of contemplation as well as a low-level sense of mounting horror that is always threatening to curdle the idyll.Also, there is probably a tropical beach party, some pagan rituals, and a tender love story in the mix as well.

Needless to say, those vivid technicolor shifts in tone make The Gone Away quite a fascinating and oft-fun cavalcade of singular and surreal scenes.In fact, I like to imagine Jupp as an incredibly talented cabaret pianist who can effortlessly play nearly any request, but who has only four possible settings on his keyboard: "harpsichord," "cartoon tuba," "Giorgio Moroder," and "big, bloopy analog synthesizer."As a result, even the most straightforward melodies feel charmingly lurching, blurting, and unfamiliar, though Jupp does occasionally downplay his propensity for big melodies to take a stab at more understated and simmering fare.That side of Jupp's artistry is best illustrated by "ffarisees," which mostly sounds like Moroder covering a somewhat haunting medieval Christmas song, yet ultimately evolves into a dazzling final act of skittering synth arpeggios that calls to mind a fireworks display erupting in an Impressionist painting. The opposite end of the spectrum is exemplified by the bouncy, burbling, and bright melodies of "Fol-de-rol," which would completely destroy my sanity if it was stuck in my head for longer than five minutes.There is a lot of stylistic room between those two poles, however, and some of it is quite good.I am especially fond of "Magpie Lane" and "Copse," which are (of course) quite different from both each other and everything else on the album.In "Magpie Lane," for example, a bittersweetly lilting melody of blobby synth tones unfolds over a clicking melody that I can only presume was provided by a tap-dancing puppet (naturally, said puppet also has a jaw harp)."Copse," on the other hand, feels like the theme music for an epic showdown between a gallant knight and some kind of shambling extradimensional fiend.

The inherent modesty and "loving homage" nature of this project precludes me from proclaiming that Jupp is a world-building iconoclast, but The Gone Away does have the feel of great outsider art.Whether or not it is fair to call the co-founder of an influential and beloved label an "outsider" is certainly up for debate, yet it is a challenge to imagine many other artists who are as far outside the zeitgeist as someone orchestrating an unholy and mind-melting collision of early electronic music, classic sci-fi kitsch, H.R. Pufnstuf, and dark folklore in 2020.Or who blurs the line between wholesome and demented so masterfully.No one can say that Jupp and his Ghost Box brethren lack vision.However, that vision would not amount to nearly as much if Jupp were not so skilled at executing it.Aside from his obvious talents for strong hooks, uncluttered arrangements, and tight songcraft, Jupp showcases a genius for something much harder to define on The Gone Away.Normally, I praise artists who skillfully combine disparate for their seamlessness, but Jupp deserves praise for his…uh…seamFULness instead, as he manages to imbue almost every piece with a clunky, self-consciously retro homespun charm.Whether or not that charm is enough to elevate this album from "endearingly strange and otherworldly" to "great" probably lies in how predisposed a given listener is towards classic BBC Radiophonic Workshop sounds, I suppose.In my case, my appreciation for the Workshop lies mostly in its historical importance, but The Gone Away's handful of highlights is delightful enough to make me wonder if I need to reevaluate that opinion.I also wonder if the real deal (Oram/Derbyshire aside) might now pale beside Jupp's inspired re-imaginings: The Gone Away is not so much like re-visiting a long-cancelled, half-remembered TV show as it is like discovering that your weird uncle built an elaborate diorama of the set in his garage and has doggedly continued the plot on his own ever since (with absolutely no dip in quality).

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This Italian composer’s latest full-length is quite a significant departure from the aesthetic of 2018's inventively shape-shifting A Conscious Effort, as Novellino decided to head in an entirely non-conceptual direction (he correctly believes that abstract music too frequently has hidden meaning and significance projected onto it in order to lure in both listeners and acclaim). In keeping with that theme, the album's prosaic title translates simply as "strings." That title is certainly apt, as sounds conjured from strings are indeed the heart of the album's aesthetic, but it is also a bit of an amusingly misleading understatement: Strängar is not an orchestral album, but is instead largely a celebration of the many vivid and visceral sounds that one can produce from an inventively misused piano. It is also much more than that though, as Novellino's cavalcade of scrapes, dissonantly jangling metal strings, and assorted percussive sounds intriguingly bleeds in and out of a very different vision of spacey, hallucinatory synth motifs. Admittedly, that sounds like a potentially unwieldy marriage on paper, but Novellino executes it beautifully to achieve a compelling and unique blurring of the boundaries between disparate worlds.

This Italian composer’s latest full-length is quite a significant departure from the aesthetic of 2018's inventively shape-shifting A Conscious Effort, as Novellino decided to head in an entirely non-conceptual direction (he correctly believes that abstract music too frequently has hidden meaning and significance projected onto it in order to lure in both listeners and acclaim). In keeping with that theme, the album's prosaic title translates simply as "strings." That title is certainly apt, as sounds conjured from strings are indeed the heart of the album's aesthetic, but it is also a bit of an amusingly misleading understatement: Strängar is not an orchestral album, but is instead largely a celebration of the many vivid and visceral sounds that one can produce from an inventively misused piano. It is also much more than that though, as Novellino's cavalcade of scrapes, dissonantly jangling metal strings, and assorted percussive sounds intriguingly bleeds in and out of a very different vision of spacey, hallucinatory synth motifs. Admittedly, that sounds like a potentially unwieldy marriage on paper, but Novellino executes it beautifully to achieve a compelling and unique blurring of the boundaries between disparate worlds.

The four numbered pieces that comprise Strängar can all be reasonably described as variations on a single theme, as all are built from a core foundation of strummed, scraped, or hammered piano strings that ultimately dissolves into a second act of simmering synth-driven psychedelia.Novellino proves himself to be quite ingenious in varying the tone and texture of his ephemeral passages, however, and the transitions between them tend to feel both organic and fluid.As a result, each of the four pieces has its own distinct character and that character steadily deepens as each unfolds.In the opening "Strängar I," a slow-moving progression of minor piano chords hangs in the air as a small-scale textural apocalypse of metallic scrapes, buzzing strings, and snarls of noise unfolds below.Unexpectedly, however, it all dissipates to reveal a sadly blooping synth melody that quickly expands into a densely layered and harmonically rich juggernaut of glimmering, undulating electronics and crunching, clattering machine noise.Since A Conscious Effort, Novellino has gotten considerably more adept at metabolizing his influences into something that feels distinctive and fresh, as the most simplistic description I can muster for "Strängar I" is that it sounds like a John Cage performance and an aggressive Tim Hecker remix of Steve Roach's Structures from Silence are blurring together in a cathedral full of industrial machinery.There are still recognizable nods to Novellino's inspirations, but their context and trajectory is never the expected one.That is an admirable bit of transformative alchemy and it is one that Novellino is able to successfully repeat again and again.It almost feels like each piece is some kind of timeless occult ritual that propels me through a portal into a futuristic landscape of neon and gleaming chrome.

In "Strängar II," Novellino opens with a darkly dissonant and rippling arpeggio pattern that sounds like an autoharp, but presumably originates from piano innards.Gradually, some more gnarled and distorted tones creep into the reverie and coalesce into a dense and erratically throbbing undercurrent.From that point on, the piece steadily evolves in a non-linear fashion, at times approximating a haunted music box or a deconstructed, time-stretched requiem mass, yet ultimately blossoming into a pointillist crescendo of shivering and streaking synth tones.That wonderful finale does not last long, but it is absolutely gorgeous while it lasts, calling to mind a slow-motion fireworks display or a melting night sky full of stars.The following "Strängar III," on the other hand, initially sounds like a jagged, heaving swirl of chiming and scraping metal strings before eventually resolving into a final act of smoldering drones and pulsing loops that slowly burns out and fades away.Both sections are likable and beautifully realized, but my favorite part of the piece lies in the transition between them, as there is a brief interlude of long, slow scrapes and metallic harmonics that threatens to steal the show long before Novellino gets to the intended pay-off.Elsewhere, Novellino saves his most memorable transformation for the album's closing statement.At first, "Strängar IV" resembles a skeleton plucking away at a rusty, cobwebbed, and strangely tuned harp as eerie metallic sounds heave and churn in the background, yet a more coherent form slowly emerges as subterranean pulses, shortwave radio noise, and tender swells of warmth snowball into a quavering and hissing dreamscape of intertwined drones. In a final twist, Novellino then slowly dissolves his elegant structure to make way for a glimmering, receding coda of hazy synth swells and reverberant scrapes and crackles.

While Strängar is an impressively absorbing and oft-haunting suite of songs in general, it is an especially wonderful headphone album, as Novellino's textures are all sharply realized and full depth of his craftmanship does not reveal itself without focused listening.Obviously, there are plenty of other artists in the abstract/experimental milieu who take sound design very seriously, but it is quite rare to encounter one who also pours the same amount of thought and effort into their overall vision or their compositional decisions.In that regard, Novellino is a welcome surprise.Admittedly, it took me a few listens to fully appreciate what he achieved with Strängar, as it is not the sort of album that instantly grabs me by the throat, but rather a quietly mesmerizing slow burn that grows deeper and more vivid with each fresh immersion.I especially love the way the pieces seamlessly transform from rippling, creaking, and scraping metal textures into sublime and harmonically rich soundscapes, as it calls to mind time lapse video of a blooming flower, but with the eerie, dreamlike sensibility of a Quay Brothers film.As a result, I am tempted to come up with some colorful term like "ghost ambient" to describe the darkly beautiful final destination that each of these four pieces reveals, but terms like "drone" or "ambient" would be misleadingly insufficient: Novellino is never content to allow his work to linger in a state of suspended animation, as subtly moving parts are always sneakily assembling the framework for the next transformation. While it is hard to say whether or not this is Novellino's best album to date, there is no question in my mind that Strängar marks an impressive leap forward in shaping his evolving aesthetic into a focused and fascinating vision that is his alone.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I was having a conversation with someone the other evening about what defines "pop" music, and if it can be considered good music. This is a loaded question since there are many varieties of music that could potentially fall into a pop category; the term means many different things, carrying both positive and negative connotations. As this isn’t meant to be an essay arguing the definition, let me simply say this: I enjoy what moves me. There exists simple, straightforward music which has the power to reel me in, winning me over with charming, catchy melodies, making my heart soar. With his sincere delivery, dreamy heartfelt melodies, eighties pop sensibilities and impressive vocal range, the talented John Jagos won me over as Brothertiger on his latest, Paradise Lost.

I was having a conversation with someone the other evening about what defines "pop" music, and if it can be considered good music. This is a loaded question since there are many varieties of music that could potentially fall into a pop category; the term means many different things, carrying both positive and negative connotations. As this isn’t meant to be an essay arguing the definition, let me simply say this: I enjoy what moves me. There exists simple, straightforward music which has the power to reel me in, winning me over with charming, catchy melodies, making my heart soar. With his sincere delivery, dreamy heartfelt melodies, eighties pop sensibilities and impressive vocal range, the talented John Jagos won me over as Brothertiger on his latest, Paradise Lost.

There has been a wave in recent years of capitalizing on '90s shoegaze and '80s new wave sensibilities—some have termed this combination "dream pop" or "synthwave"—with varying success. Brothertiger mellows it out, unabashedly coating the sound in smooth electronics and hefty homage to '70s pop. This is immediately evidenced on the opening track "Found" as dreamy electronics build to make room for cool, but danceable rhythms, Jagos’ voice reminiscent of an alto choir boy soaring over the unassuming melody. It’s like a little slice of paradise.

But all is not well in paradise. The album is filled with beautiful moments like this, a "happy little tree" that may joyfully be consumed without effort. But listen more carefully to the lyrics, and the title begins to hint at the layers of this album. At first glance, "Mainsail" starts out like a guilty pleasure, a familiar sunny tune from the '70s, reminiscent of a warm sail on clear waters—but Christopher Cross’ "Sailing" never started out with "Can’t you recognize my face in a crowded room? Living in the Empire State, I’m lost sometimes."

The album is nearly impeccable, growing on me with each listen. The first time hearing "Livin’" was a warm welcome, but I wasn’t quite sure to make of what I initially deemed a "pop ditty." On further listens, the song seemed darker than I remembered it. More layers were uncovered after I read the lyrics: "Honestly, I can't keep my head up high / Honestly, I can't get a hold on life."

The album’s title is indicative of the album as a whole. The music is crafted to sound like pure sunshine, a window into paradise, warm and relaxing, but with enough layers to make things interesting, getting lost in deceptively simple melodies. "Shelter Cove" is my favorite track, offering warm solace, a comforting melody and hopeful lyrics: "The silence / We'll find it / In our hideaway / The fog lifts / Beyond us / Open out Pacific bay." Enjoy it for what it is; it is fine to stay right here, cuddly and warm. Freud once said that sometimes a cigar is just a cigar, but there is more than simply meets the eye to Brothertiger.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

A truly multinational project, Staraya Derevnya is a collaboration of artists, poets and musicians across Israel, London and New York, released on independent record label Raash Records out of Jerusalem. The lyrics are sung, screamed, and chanted in a combination of Russian merged with a made-up language, with only the track titles — derived from a line of each song — translated to English. Knowing Russian is not required to be transported into a journey of epic aural proportions.

A truly multinational project, Staraya Derevnya is a collaboration of artists, poets and musicians across Israel, London and New York, released on independent record label Raash Records out of Jerusalem. The lyrics are sung, screamed, and chanted in a combination of Russian merged with a made-up language, with only the track titles — derived from a line of each song — translated to English. Knowing Russian is not required to be transported into a journey of epic aural proportions.

With a background in art, my attention was drawn to the cover, an inspiration from Russian interactive multimedia artist (and sometimes group member) Danil Gertman. There has been a lot of discussion around my house as to what the image conveys, with dripping lines of paint like blood, the presence of a floating (or falling) figure, perhaps not quite human. As with all art, the image is open to interpretation, and both the artwork as well as Staraya Derevnya focus on feeling over message.

The collective utilizes a collection of seemingly disparate instruments in their sound creations: toys, radio interference, kazoo, electric cello, theremin, synths, melodica, dulcimer, bass clarinet, flute, piano, and drums, as well as many others. Heck, there’s even a rocking chair in here somewhere. Yet, it all works supremely well, the collective working in a guided experimental spirit. The feel of Inwards opened the floor. is initiated by the sound of disarray, a track held together through repeated piano notes and a modulated vocal refrain, vocals, washing over layers of increasingly chaotic drone, irregular drumming, and ambient sounds. From there, "'Chirik' is heard from the treetops'' offers an industrial dance rhythm with underlying ominous bass notes. A kazoo and pulsating theremin chime in, while the vocalist yelps and howls as if possessed by Blixa Bargeld. Everything works seamlessly, until finally abruptly sputtering out for jarring effect.

Double bass and cello form a chilling backdrop on "Flicked the ash in kefir'' before a clatter of chains crates a distraught rhythm, accompanied by the impassioned, near screams of the vocalist, building in chaotic saxophone for added tension before pulling back into beautiful ambient drones. Probably my favorite track, the song is billed as a kind of "Christmas song" which translates:

"Powder Snow. Someone's trail. Grayish Day Winter realm. Faint Light You flaked out. As if Flicked the ash in kefirMany Years. Wait for candy. Smell Pine Inhale. New Year Magic hour. As if Childhood once more upon us"

There is no "theme" here as a whole: this is primal music, focusing on intonation and feel, a journey of aural movements. And in that, it succeeds. While listening to "Flicked the ash in kefir" prior to seeing the translation, I was transported to a place of darkness. Reading the lyrics, I am reminded of the earliest Christmases I enjoyed in innocence and happiness, before they were impacted by traumatic life events like divorces, distance, and deaths. The song then took on a new, more personal meaning: the muddying of purity, like flicking ashes into kefir, and the yearning to return to a more innocent time.

"Burning bush and apple saucer" is a conversation of sorts, initially between male and female, that moves into urgency by the male, as if the conversation has broken down. The song invokes waves of pain, an urgency to comfort and be comforted. While I may not know much of what’s being said, that’s the beauty of this album — I don’t need to know the language. Good music is transcendental, separate from any language, and a distinct language like no other. Staraya Derevnya nails it.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

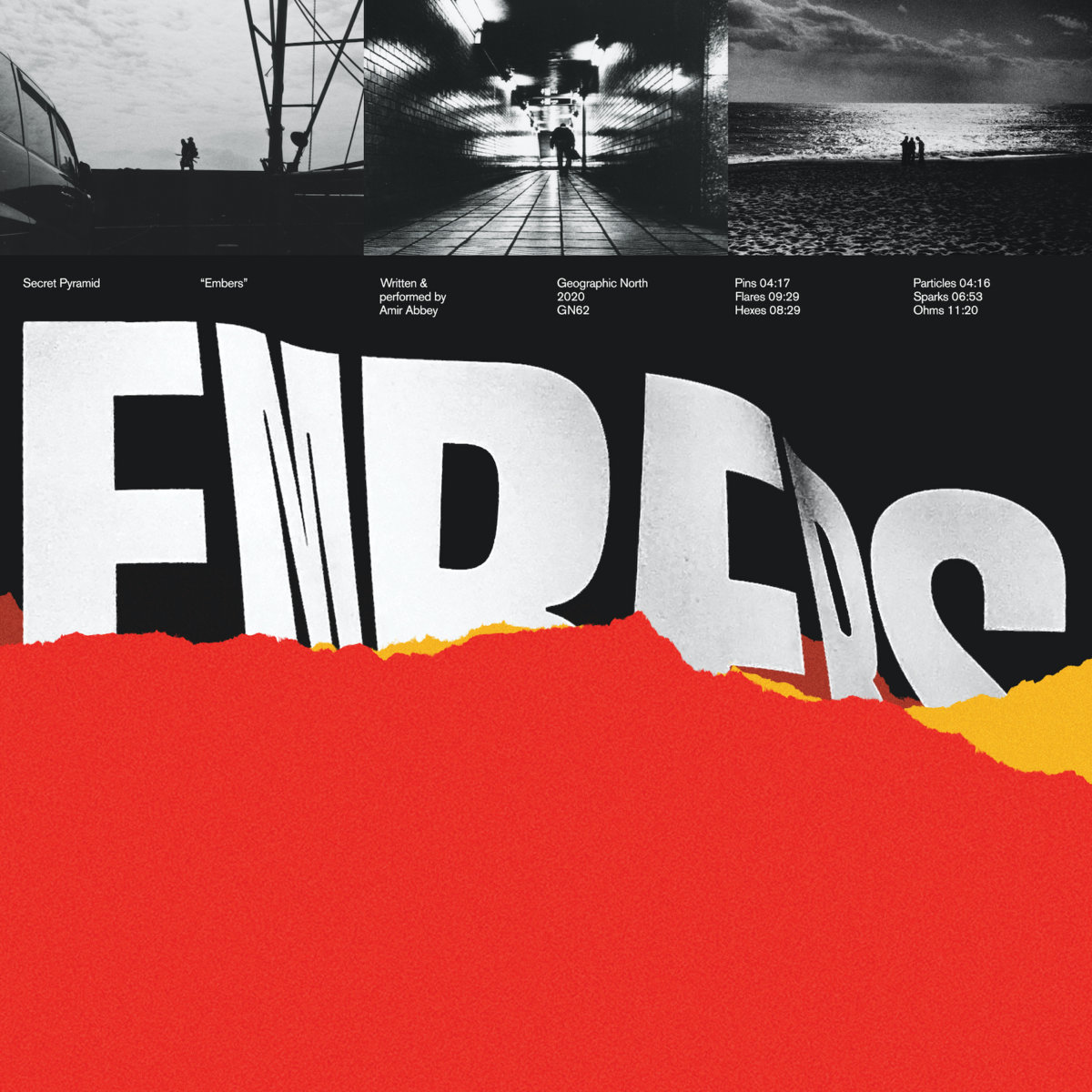

Embers: the smoldering or glowing remains of a fire. Something fading, but still capable of pain when touched. The transition of a bright flame being extinguished into darkness, mirroring the cycle of day into night. Vancouver-based composer Amir Abbey is Secret Pyramid, creating his transcendental neo-classical dreamworks at night, giving light to meditative sonic works that sound at home in a cathedral, offering sonorousness of awe and sorrow echoing majestically through vast space and settling in the soul. Abbey’s latest, Embers, works magic in these ways, offering a "less is more" approach creating the aural equivalent of wide open spaces filled with tranquillity and ephemerality.

Embers: the smoldering or glowing remains of a fire. Something fading, but still capable of pain when touched. The transition of a bright flame being extinguished into darkness, mirroring the cycle of day into night. Vancouver-based composer Amir Abbey is Secret Pyramid, creating his transcendental neo-classical dreamworks at night, giving light to meditative sonic works that sound at home in a cathedral, offering sonorousness of awe and sorrow echoing majestically through vast space and settling in the soul. Abbey’s latest, Embers, works magic in these ways, offering a "less is more" approach creating the aural equivalent of wide open spaces filled with tranquillity and ephemerality.

Abbey is known to frequently work with an Ondes Martenot, an early electronic instrument (late 1920s) played by running a ring along a wire, and sounding much like a theremin or an effected-treated cello. This instrument continues to be utilized on Embers, along with string, field recordings, loops and distortion. The balance of these, drawn out and diffused, provide a subtle arrow to the heart.

Abbey’s work has conceptually addressed emotive topics through composition and track titles, as can be seen and heard on such prior works as Two Shadows Collide and Movements of Night, but Embers served as a musical exorcism for Abbey as he struggled to process a very turbulent period of his life. Consequently, the album showcases both grief and tranquility, and the minimalism allows the emotions to ebb and flow with ease.

Each track title seems to suggest the possibility of embers, or in some way with a connection to embers: "Flares," "Particles," "Sparks," "Ohms." Abbey himself has explained, "It’s a reflection of the impermanent, shifting, and fleeting aspects of our lives, both the good and the bad, that often spark something inside of us." This is an album suited for reflective times, but the sounds flow just as easily as a cinematic orchestration, in the vein of an Angelo Badalamenti score. The beauty of this album is hinted at the album’s title, providing a gentle, fading burn that is deceptive in it’s soft glow.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Shapeshifting producer Marc Richter offers up another powerfully psychedelic collection of hypnagogic sound collages and electronic meditations.

Oocyte Oil & Stolen Androgens compiles new evolutions of pieces originally created as art installations alongside original pieces, demonstrating the sheer breadth of Black To Comm's sound world and distilling an incredible amount of sonic detail into, surprisingly, some of Richter's most instantly arresting and concise works to date. A deeply immersive listen that recalls The Caretaker's deep dives into the subconscious or Felicia Atkinson's synaesthetic compositions.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

A new Microphones album consisting of one long song.

Here is a poem about it:

The old smell of air

coming faintly through the spring

crack in the snow above a hibernating bear’s winter den,

the smell of long self-absorption,

burrowing into one’s own chest, re-breathing the exhales of one’s own breath,

the smell of squinting in the dark

ruminating in dreams

beneath layering years, the snow still falling.

In the dark smoldering

slowly burning through all the old clothes, sifting through the ash,

wiping old shedded fur from the eyes

nosing out into the light.

In that brief moment when the airs of the past and present meet,

at the mouth of the open bed,

egoic solidity burns away in the spring wind, self becomes fuel,

there is only now

and the past is a dream burning off.

Fragments arranged along the trail, crumbs consumed, dust blown,

no route back.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

"As a child, almost every Sunday, I was wandering in the countryside, and usually, I was finding myself in my favorite spot: a swamp. Air was different. Trees were dead, but not really dead. Soil was swaying of clear water, and an everlasting mist was suspended all over the place. No one was there and nothing could happen even if some animal tracks were here to prove me I was wrong.

Much later, one of my masters made always this joke about my music. He said I was composing swamps, I guess because of the lack of demonstrative musical shapes and articulations. At the same time, he was acknowledging that I was building a “climate."

It took me then almost 30 years to understand why I was so fond of swamps. It's because a swamp is an intermediary space of the organic becoming and the blurry space suspending the cycle of the utilities, which is the cycle of history.

Swamps / Things has been conceived as an opera. An opera without characters, without text, but not without story. The story, here, is only an arc. Because what is an opera, if not an arc? And the arc, here, is the simplest. It's walking through the swamp.

Approaching it, leaching into it, becoming it. The Swamp is us. Our own disappearance, populated by all the beasts we have turned into, by the places we have haunted, and by the time we have consumed. We are traces in an always intermediate state. Animals tracks in the sodden earth of the Swamp."

— Francois Bonnet (Kassel Jaeger).

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Much like everyone else with a deep interest in experimental music, I have spent a good amount of time exploring the more avant-garde side of 20th century classical music. Estonian composer Arvo Pärt is admittedly not an artist who fits particularly comfortably in that milieu, as he took a far more unique and anachronistic path than most of his peers and embraced Gregorian chants and simple melodicism rather than dissonance, conceptual art, complicated harmonies, electronics, or Eastern drones. That path has rightfully made him one of the most frequently performed contemporary composers, but his work did not make a deep impact on me until I heard the sublime "Spiegel im Spiegel" in Gus van Zant's similarly sublime Gerry. After that revelatory experience, I immediately dove headlong into Pärt's classic ECM albums and they have been a fixture in my life ever since, but I was completely unaware of this album (originally released on the German label Beaux in 2001). Now that it has been reissued, I can see why these pieces did not initially make the same cultural impact as some of Pärt's other work, but I can also see why they eventually found an audience regardless: Works for Choir feels like a dispatch from an alternate timeline in which Bach was never shouldered aside by folks like Schoenberg and Stravinsky and simple beauty never fell out of favor.

Much like everyone else with a deep interest in experimental music, I have spent a good amount of time exploring the more avant-garde side of 20th century classical music. Estonian composer Arvo Pärt is admittedly not an artist who fits particularly comfortably in that milieu, as he took a far more unique and anachronistic path than most of his peers and embraced Gregorian chants and simple melodicism rather than dissonance, conceptual art, complicated harmonies, electronics, or Eastern drones. That path has rightfully made him one of the most frequently performed contemporary composers, but his work did not make a deep impact on me until I heard the sublime "Spiegel im Spiegel" in Gus van Zant's similarly sublime Gerry. After that revelatory experience, I immediately dove headlong into Pärt's classic ECM albums and they have been a fixture in my life ever since, but I was completely unaware of this album (originally released on the German label Beaux in 2001). Now that it has been reissued, I can see why these pieces did not initially make the same cultural impact as some of Pärt's other work, but I can also see why they eventually found an audience regardless: Works for Choir feels like a dispatch from an alternate timeline in which Bach was never shouldered aside by folks like Schoenberg and Stravinsky and simple beauty never fell out of favor.

While he certainly evolved into an iconoclastic composer by the time he reached middle age, it is worth noting that Pärt did not instantly burst onto the scene with a fully formed aesthetic of his own and mostly spent his early years in the thrall of the usual classical influences.I say "mostly" because Pärt's native Estonia was controlled by the Soviet Union for much of his life, which made it difficult to acquire music that was not government-approved.In fact, Pärt's own early twelve-tone-inspired works were themselves banned by Soviet censors, triggering both a deep depression and "the first of several periods of contemplative silence, during which he studied choral music from the 14th to 16th centuries."Eventually he started composing again, but after finishing his Third Symphony (1971), he started looking even further back for inspiration, immersing himself deeply in early religious music like plainsong and Gregorian chant.Unfortunately, the Soviet authorities were not fond of his religious-themed work from this period either, so his problems and frustrations continued.Happily, however, the Arvo Pärt that we all know and love reinvented himself and re-emerged to enter his most fruitful creative period in the late 1970s, as many of his best-loved and most influential works were composed during a single stretch when he was in his early forties.That chronology is interesting because the more overtly conventional pieces collected on Works for Choir date from roughly a decade later (1988 -1991).In some ways, that curious progression makes sense, as Pärt's trajectory seems to have been one leading to greater heights of both religiosity and simplicity, yet he still remained a deeply adventurous composer in his compositional techniques.

For the most part, almost none of these eleven pieces would result in a raised eyebrow if they turned up in a Christian mass (Pärt converted to Orthodox Christianity in the early 1970s), though the opening "The Beatitudes" does feel unusually intense and bracing for such fare.Part of that is due to the almost darkly psychedelic organ finale, but there are also several unusual compositional tricks at work before that point.The text of the piece (in English) is taken from The Sermon on the Mount, but Pärt emphasized passages by writing each "each clause…in a different harmonic key" while "the central pitch of the recitation constantly rises, increasing the tension."Then, after the crescendo, the same process unfolds in reverse.All of the album's other major stand-alone pieces follow soon after, though "Magnificat" and "Nun eile ich zu euch" seem to hew fairly closely to the expected Christian choral tradition.Both are, of course, quite beautiful.They just are not particularly radical.I suppose "Summa" is not all that overtly radical either, but is an achingly gorgeous album highlight with an intriguing history.According to the original CD, the piece dates from 1990, but the choral version that appears here actually dates back from Pärt's late ‘70s heyday.He has since repurposed the piece several times as an instrumental work, however, which makes sense: its lyrical basis in the Latin Credo would not have been acceptable to Soviet censors, so Pärt gave it both a title that "hides a coded message" and a circular structure that "conveys a symbolic meaning."The remainder of the album is devoted to a series of shorter pieces that collectively form "Sieben Magnificat – Antiphonen," a collection of prayers (in German) composed in Pärt’s signature tintinnabuli style.While intended as a seven-part whole, the various sections were designed to contrast each other various ways, so it is not uncommon for individual sections to be performed by themselves.

Sadly, my grasp of early religious music and Pärt's compositional intricacies is not quite deep enough for me to fully appreciate the various innovations lurking in the structure of these pieces, nor am I sufficiently versed in Christianity to grasp the deeper meaning of the texts Pärt chose.As such, Works for Choir does not feel nearly as singular or subversive as it might seem to a classical music scholar.Instead, it feels like excerpts from an especially good religious mass composed in an earlier time, which is just fine by me.It almost makes me nostalgic for a less secular era: while the old adage that the devil gets all the good music certainly has some truth to it, it is equally true that a passionate belief in a higher power has inspired quite a lot of towering masterpieces of both music and architecture over the years.It is certainly hard to imagine either Simon Finn or David Tibet reaching their most fiery heights without some kind of spiritual drive behind them and the same is true of Pärt.While Works for Choir does not disabuse me of my firm belief that Pärt reached his creative zenith in the late '70s, my only real issue with this album is that it blurs together with the work of other composers in a way that his finest work does not.Within the context of Pärt's oeuvre, these pieces are more significant as a document of his evolution than as a crucial album, though I would certainly feel comfortable including "Summa" and "The Beatitudes" among his landmark works.Within the context of classical music as a whole, however, Works for Choir is a strong collection that scratches roughly the same itch as a Bach mass or the better work from Pärt's fellow holy/mystic minimalists like Tavener or Górecki.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

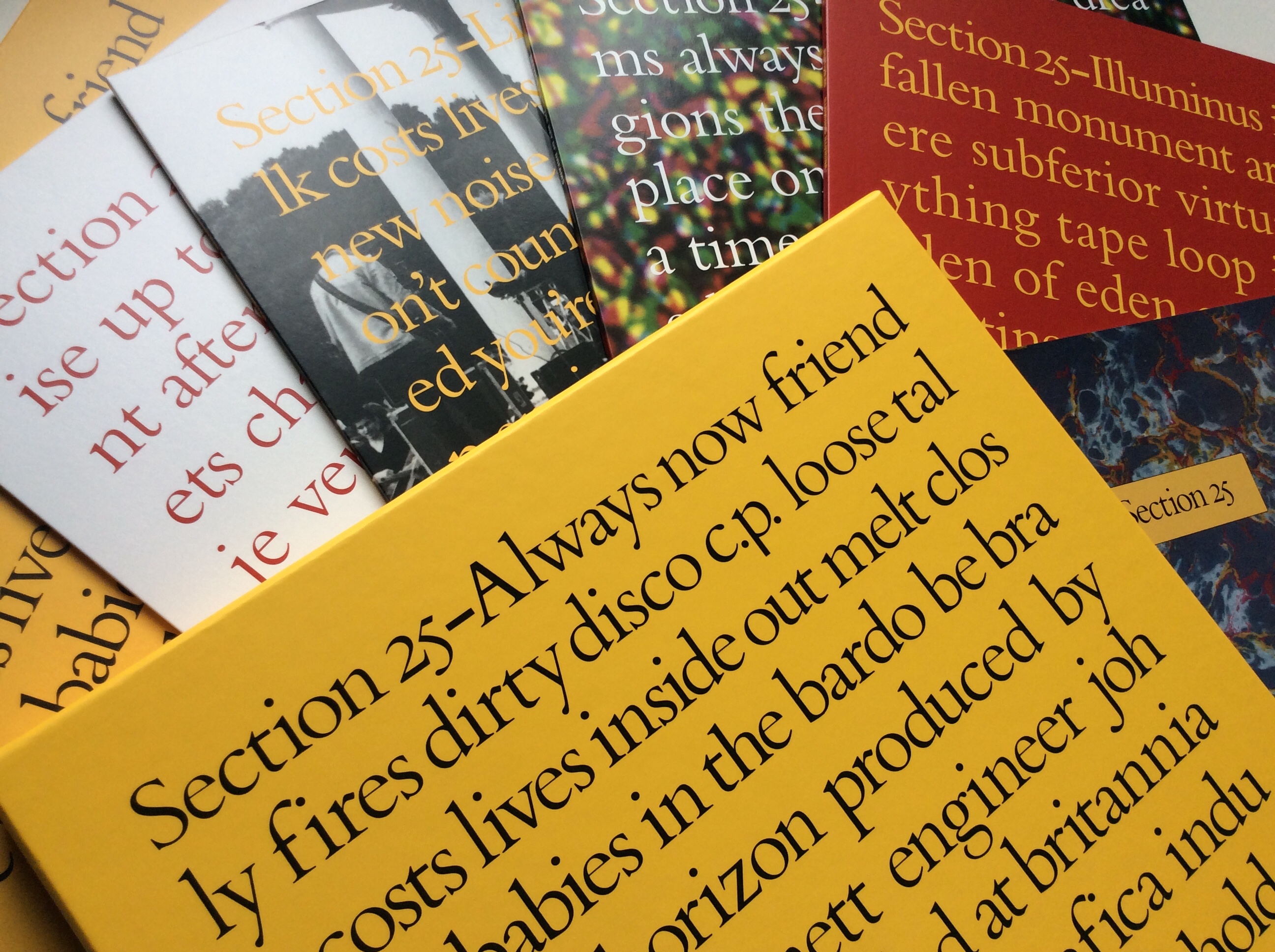

Section 25 epitomize an uneasy classification of "post-punk," combining raw electronics, cast over with early shadows of gothic rock despair, and blended with a healthy dose of stark krautrock and sometimes even *gasp* danceable rhythms, fronted by tuneless, disaffected vocals. This formula has served countless experimental bands well that followed into today. This gorgeous 5 disc vinyl (or 2 CD) set of Always Now from Factory Benelux allows listeners old and new to dig deeper into the musical expanse of early Section 25.

Section 25 epitomize an uneasy classification of "post-punk," combining raw electronics, cast over with early shadows of gothic rock despair, and blended with a healthy dose of stark krautrock and sometimes even *gasp* danceable rhythms, fronted by tuneless, disaffected vocals. This formula has served countless experimental bands well that followed into today. This gorgeous 5 disc vinyl (or 2 CD) set of Always Now from Factory Benelux allows listeners old and new to dig deeper into the musical expanse of early Section 25.

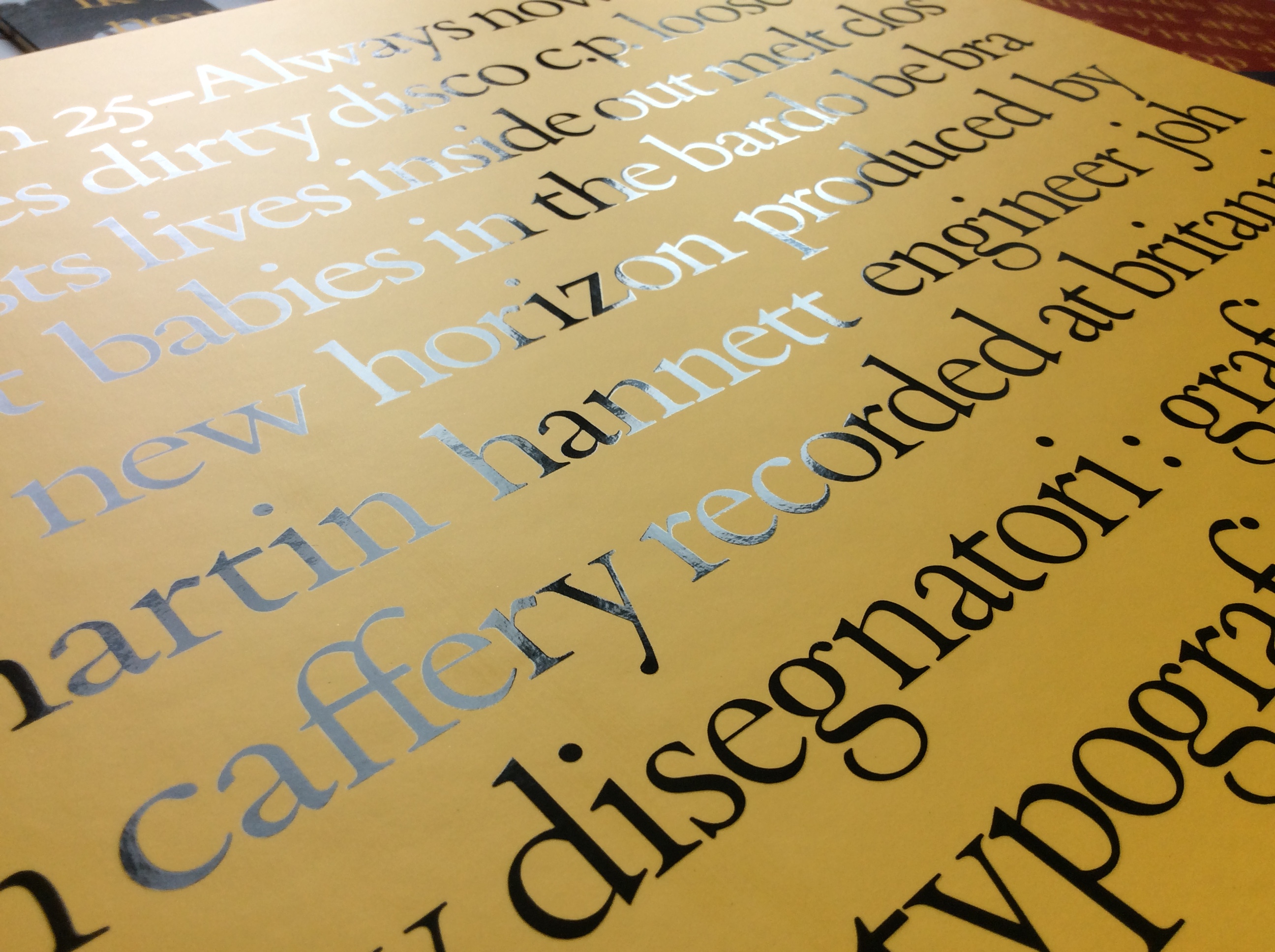

The original cover art is well-known in graphics design circles for being a typographical and visual masterpiece; it was Factory’s most expensive design ever. The outer case was printed in a strikingly solid PMS 123 with spot varnish, and designed to appear like a matchbook, textured with a "waxed" appearance. The typography emulates the Berthold font, using a repurposed Phil’s Bembo specimen and Bakserville fonts to craft a unique font for the album, and further accentuated by adding unhyphenated linebreaks. If you look very closely at the bottom of the typography, you will notice "16.5mm (60p)" which shows the character scale used. The first 1000 copies of the vinyl box set are additionally pressed in colored vinyl (black, clear, silver, yellow, red).

The original cover art is well-known in graphics design circles for being a typographical and visual masterpiece; it was Factory’s most expensive design ever. The outer case was printed in a strikingly solid PMS 123 with spot varnish, and designed to appear like a matchbook, textured with a "waxed" appearance. The typography emulates the Berthold font, using a repurposed Phil’s Bembo specimen and Bakserville fonts to craft a unique font for the album, and further accentuated by adding unhyphenated linebreaks. If you look very closely at the bottom of the typography, you will notice "16.5mm (60p)" which shows the character scale used. The first 1000 copies of the vinyl box set are additionally pressed in colored vinyl (black, clear, silver, yellow, red).

Musically, when Always Now came out in 1981, the band still had the aura of Ian Curtis over them who, as a friend of the band, had earlier produced the single "Girls Don’t Count" later included on reissues of the album. As fantastic as that song is, Section 25 have always had far more to offer, and this set breaks it down. For the vinyl set, the first disc covers the primary album, while Disc 2 pulls together non-album singles ("Charnel Ground", "Je Veux Ton Amour" and the aforementioned "Girls Don't Count").

Disc 3 is a complete 1980 live show in the Netherlands that was a complete Factory package tour. Disc 4 is the excellent studio album The Key of Dreams, a 1982 disc of partially improvised works that came about only a few months after the release of Always Now. Disc 5 covers their experimental output that was originally released on cassette as Illuminus Illumina prior to the band’s brief breakup.

Both discs 4 and 5 showcase their excellent improvisational ability. Starting with disc 4, "Visitation" offers an onslaught of gloomy, swirling psychedelic gothic instrumentation and sound effects, suitable alongside a good chunk of today’s tribal psychedelic gloom mongers (Föllakzoid comes to mind), while "Regions" may easily be mistaken for a Throbbing Gristle or Psychic TV track. On disc 5, opening track "Fallen Monument" shows the band venturing into ambient electronics territory, while the rest of the disc has them in experimental gloom mode. One wonders where these would have ended up if they had been polished into full-fledged tracks. Of note is an extended live jam with the members of New Order at Reading University, shortly after Ian Curtis’ death in 1981, that offers a glimpse into their free-form prowess.

While a set of this size is bound to have some filler, it is thankfully kept to a minimum here, and brought together in a lovingly crafted package. This is not a set only for diehard Factory fans. It is a snapshot of an era, and a picture of a band that, despite an underground status, has remained true to itself despite never achieving the massive success of some of their Factory peers.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

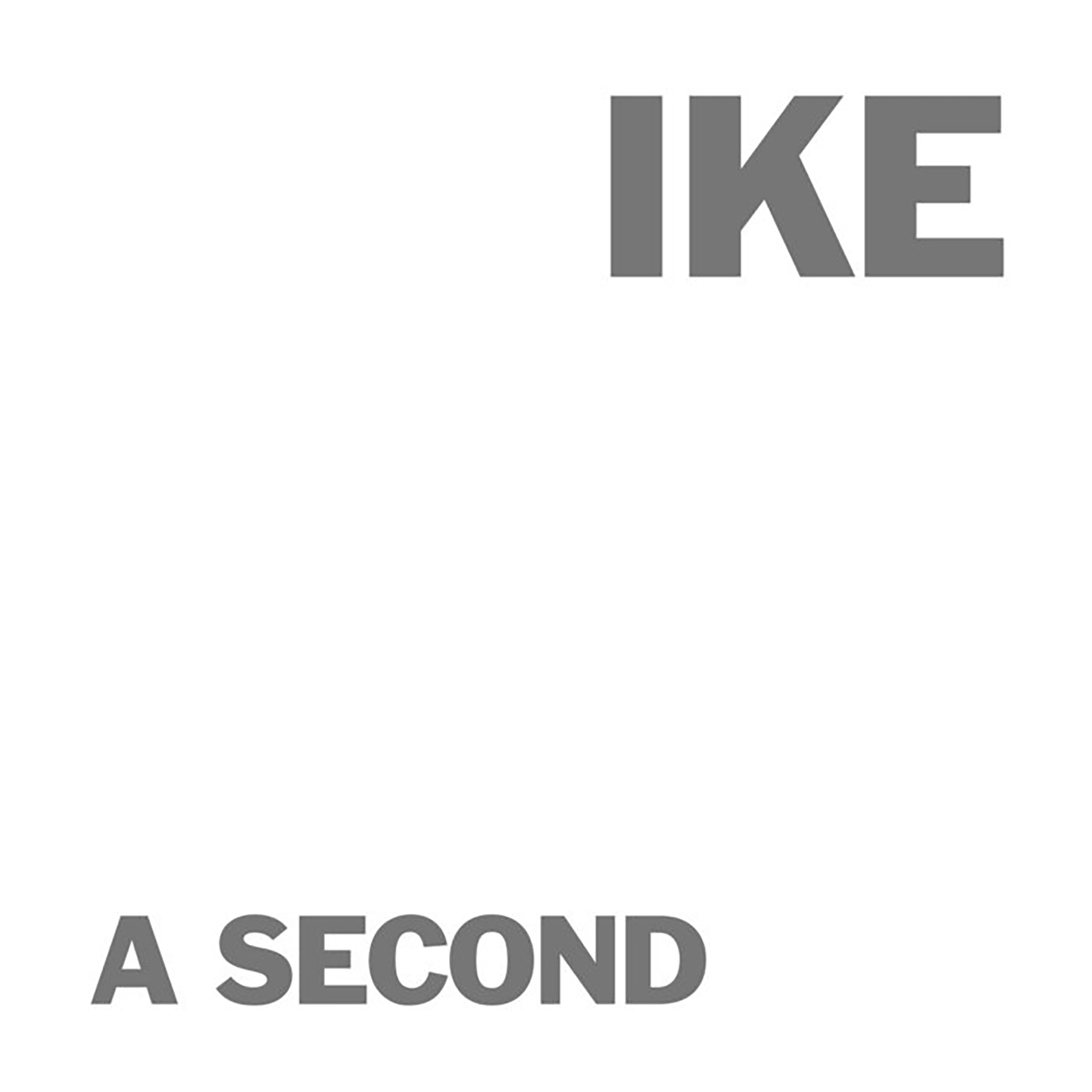

Originally released back in 1982 on Factory America, Ike Yard's debut full-length has been one of those rare records which rightfully lingers in the cultural consciousness as a very cool influence to reference, yet somehow remains perplexingly underheard. That is a damn shame and I hope this latest reissue from Superior Viaduct wakes some more people up to Ike Yard's incredibly forward-thinking moment of white-hot inspiration, as these NYC No Wavers deserve to be every bit as revered as their similarly out-of-step peers Suicide. Granted, Suicide definitely wrote better songs than Ike Yard, but Ike Yard were on an entirely different trip altogether and their aesthetic has aged beautifully in the ensuing four decades. In fact, if some Brooklyn band released this exact album today, I am positive that it would be all over "Best of 2020" lists and it would not be because of retro nostalgia: Ike Yard perfected their strain of tough yet arty minimalism so spectacularly that it still feels cutting edge today. Obviously, shades of this foursome's stark, bass-driven grooves can be found all over the darker, heavier side of contemporary techno, but that is not why this album deserves to be heard: it deserves to be heard because it still holds up as an absolutely killer album today.

The first time I heard this album (alternately known as A Fact A Second due to the cryptic cover art), I had a very hard time wrapping my head around the fact that Ike Yard was a full band rather than just one or two guys with some pedals, a drum machine, and a primitive sampler.Part of that is obviously due to the aggressively minimal nature of the music, as these six songs are so single-mindedly focused on the groove that everything else seems like an afterthought (I like to imagine that guitarist Michael Diekmann spent the bulk of his time during shows expectantly waiting to contribute a single string scrape or similarly non-musical bit of texture).Beyond that, however, it simply seems wildly improbable that four separate people could have possibly been on this same futuristic wavelength at once.It seems safe to say that Ike Yard were probably influenced by their contemporaries in the No Wave milieu and pioneering industrialists like Cabaret Voltaire, but those other artists feel self-consciously experimental in a way that Ike Yard does not: this album feels like an almost supernaturally assured artistic statement by a band that knew exactly what they wanted to do and executed that vision with surgical precision.These songs all feel chiseled to diamond-like perfection and deftly avoid anything that might feel dated, clumsy, derivative, or indulgent by today's standards (or any standard, really).Viewed uncharitably, one could argue that Ike Yard achieved that feat by simply excising just about everything that makes music feel like music.In particular, vocalist Stuart Argabright seems especially devoted to that approach, as his rare contributions consist entirely of a few lines of cryptic, deadpan spoken word.Somehow, however, that all suits the band's weirdly lurching and blurting robot funk perfectly.While other bands on Factory were awkwardly figuring out how white people could be plausibly funky, Ike Yard were already imagining what dance music might sound like in an entirely post-human world (and nailing it).

The centerpiece of the album (and probably of Ike Yard's career as well) is the tensely simmering second piece, "Loss."Over a stumbling off-kilter beat, percussive-sounding guitar harmonics, and a dubwise bass line, Argabright blankly delivers a monologue that fades in and out of focus amidst fitful snare eruptions and chopped, sputtering squalls of sampled voices.I am especially fond of the chopped voices, as it sounds like a strangled radio transmission is constantly threatening to overpower the song, yet keeps disintegrating before it can succeed.The other five songs could have probably benefited from a similar twist, but in general the grooves are muscular and alien enough to hold up without any kind of leftfield stab at a "hook."The opening "M. Kurtz" fares especially well in that regard, as its shambling rhythm feels simultaneously ridiculous and brilliant, as it calls to mind a cartoon tuba jamming with a broken, disjointed drum machine pattern.Despite that unpromising foundation, the addition of Argabright's mumbled vocals and Kenny Compton's insistent bass line somehow transform those seemingly disparate parts into something that seems weirdly cool and purposeful.My other favorite piece on the album is "Kino," but the only real difference between the better pieces on the album and the more forgettable ones is merely the degree to which the band flesh out their skittering and stumbling grooves."Kino" features some moaning, atmospheric guitars; other songs are essentially just bass, drum machine, and mumbled vocals.To Ike Yard's eternal credit, however, that machine-like repetition coupled with splashes of snare drum violence is usually enough to make a compelling song, even if the band seemed to have an almost willfully self-sabotaging approach to rhythm: aside from "NCR," every single song feels like a deliberate attempt to conjure up a groove so erratic, bizarre, and awkward that non-spasmodic dancing is nearly impossible.

Lamentably, Ike Yard broke up in 1983 before they got a chance to record a second album, which actually seems entirely appropriate to me: after distilling post-punk to its most muscular and stark extreme, it is hard to imagine where they could have gone next.Also of note: being this crazily far ahead of the curve tends to be financially ruinous, though the band must have had a significant enough following to attract the attention of Factory (Ike Yard was their first American signing).There is a happy ending though, as more than two decades later, three-fourths of the original band reformed for a considerably more prolific second act (including several remix EPs featuring fans like Regis and Tropic of Cancer).Nevertheless, this original full-length still calls to mind the famous Brian Eno quote about The Velvet Underground & Nico (not many people bought that album, but the few who did all started bands of their own).It also improbably reminds me of a review I once read of Prong's impressively ugly Beg to Differ that proclaimed that it sounded like a scarier version of Metallica that got into beer bottle-eating contests with skinheads.Thankfully, Ike Yard sounds nothing like any era of Metallica, but this album begs a similar analogy: this is what Jamaican dub would probably sound like if it had emerged from a bombed-out, post-apocalyptic squat in Berlin rather than sunny Kingston.It may not be a perfect album, as its hookless monochromatic minimalism inherently makes all the songs sound similar to one another, but none of that matters because the aesthetic itself is so singular and wonderful.Few albums deserve a high-profile reissue and a chance at a second life as much as this one.

Samples can be found here.

Read More