- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Boston-based string maestro Joseph Allred quietly releases, on average, around three or four albums a year, a catalog consisting of mostly instrumental works with vocals on an occasional song. This set of instrumentals consists of five examples of technical fingerpick showmanship that surrounds listeners with an outpouring of emotive musical warmth, wordless stories that communicate straight to the soul.

Boston-based string maestro Joseph Allred quietly releases, on average, around three or four albums a year, a catalog consisting of mostly instrumental works with vocals on an occasional song. This set of instrumentals consists of five examples of technical fingerpick showmanship that surrounds listeners with an outpouring of emotive musical warmth, wordless stories that communicate straight to the soul.

It would be quite easy to define Allred as a fingerpick guitarist, or group Allred into the Guitar Soli category, a solo acoustic guitar movement that flourished between 1966 and 1981 and bridged a gap between American Primitivism (John Fahey, Robbie Basho) and California Modernism (Michael Hedges, William Ackerman). Yet, this barely scratches the surface of the broad work and mind of Allred.

Joseph started releasing work as a solo artist in 2013, and became a practicing artist around the same time. The cover of The True Llight displays an obvious jumble of information in the form of magazine words and headlines (the most visible word being "chatter") and a warm-colored fiery light that seems to emanate from the center of it all, almost as if it were burning its way through the chaos. The title itself seems to stem from biblical reference in John 1:9: "The true light that gives light to everyone was coming into the world." With pieces like "Who Will Heal Your Wounds," "Bethsaida," and "A Wreath for the Head," Allred quite clearly embraces religious imagery on this album. Although there are no words at all, the passion by which the songs are executed make the topic of conversation quite clear; regardless of the listener’s religious affiliations, the evocative musical flow work to take the listener on a transcendental journey of heartful proportions, a seamless weave of sounds joyful and sad, soft and intense.

Since starting a musical journey in 2000 playing electric guitar in rock bands, Allred has created various incarnations, each one serving as a persona through which to craft musical stories that revolve around innate truths. A previous incarnation was Poor Faulkner, a lonely middle-aged man dealing with deep, inner sadness and haunted by ghosts, some of his own making, and embarking on a journey to transcend the trappings of humanity.

Allred began composing music for acoustic guitar as a way to deal with personal demons — demons that nearly lead to death. Between music as an outlet and weaving the practice of mindfulness into that art, thankfully Allred has continued to not only produce a catalog of deeply meaningful and genuine human expression through music for personal benefit, but one that extends to others as a musical panacea for the troubled soul.

Read More

Boston-based string maestro Joseph Allred quietly releases, on average, around three or four albums a year, a catalog consisting of mostly instrumental works with vocals on an occasional song. This set of instrumentals consists of five examples of technical fingerpick showmanship that surrounds listeners with an outpouring of emotive musical warmth, wordless stories that communicate straight to the soul.

Boston-based string maestro Joseph Allred quietly releases, on average, around three or four albums a year, a catalog consisting of mostly instrumental works with vocals on an occasional song. This set of instrumentals consists of five examples of technical fingerpick showmanship that surrounds listeners with an outpouring of emotive musical warmth, wordless stories that communicate straight to the soul.

Boston-based string maestro Joseph Allred quietly releases, on average, around 3 or 4 albums a year, a catalog consisting of mostly instrumental works with vocals on an occasional song. This set of instrumentals consists of 5 tracks of technical fingerpick showmanship that surrounds the listener with an outpouring of emotive musical warmth, wordless stories that communicate straight to the soul. One of the most talented guitarists today, Allred is recommended if you recognize the names Fahey, Basho, Jansch, or Kottke -- Allred is all of those mentioned, and much more. If you're new to Allred's catalog, this is a gorgeous entry point to get introduced.

Boston-based string maestro Joseph Allred quietly releases, on average, around 3 or 4 albums a year, a catalog consisting of mostly instrumental works with vocals on an occasional song. This set of instrumentals consists of 5 tracks of technical fingerpick showmanship that surrounds the listener with an outpouring of emotive musical warmth, wordless stories that communicate straight to the soul. One of the most talented guitarists today, Allred is recommended if you recognize the names Fahey, Basho, Jansch, or Kottke -- Allred is all of those mentioned, and much more. If you're new to Allred's catalog, this is a gorgeous entry point to get introduced.

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Composed, performed & mixed by Heather Leigh "at home with the window open” in Glasgow, the fifth release in our Documenting Sound series is a shocking half hour of music; a 13 track opus that is, by any measure, nothing short of a modernist folk masterpiece. Recorded quickly and instinctively in April this year and described by David Keenan as sounding like "a cross between Meredith Monk, DOME and A Guy Called Gerald," it continues to reveal new dimensions with every listen.

Heather Leigh is a musical polymath in the truest sense of the word; primarily known as an influential practitioner of pedal steel guitar, her work is impossible to pigeonhole - all-over-the-place in the best way, from collaborations with Peter Brötzmann and Shackleton to a properly mind-bending duo of albums for Stephen O’Malley’s Ideologic Organ and Editions Mego - hers is a sound that’s both highly sensual and aesthetically aggressive, beautiful and fearless, always exploratory.

Played on pedal steel guitar, synthesizer and cuatro, and featuring Heather Leigh's voice throughout, the songs here capture a sense of physical longing wrapped up in a boundless creative energy. What started out as hours of diaristic recordings quickly became honed and crafted into powerful and highly memorable songs - vast in scope and depth of feeling. It’s hard to fathom that these 13 songs were made on the hoof, they capture that most elusive of artistic qualities - a compulsion to evolve.

Working on this series has been a real eye-opener for us, a thought experiment turned real - what happens when an established artist is asked to produce material quickly and without much pre-planning or afterthought? The answer, so often, has been an immense pleasure to behold. But this one, this one’s unreal.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Longform Editions 14 presents four new immersive listening experiences, featuring Carmen Villain’s atmospheric fourth-world expansions, two ambient masters in Japan’s Chihei Hatakeyama and Will Long’s Celer project, as well as piano minimalism from New York composer Michael Vincent Waller. These artists’ works investigate sound, listening and environment to engage you in a space for a period that reminds you there is a present beyond the clutter of our everyday.

Carmen Villain

Affection in a Time of Crisis

LE053

Norway's Carmen Villain creates a cosmic atmosphere with a narcotic pull, offering an enveloping space where emotive resonance rules over experimentation.

"Listening to something for a long time reveals new layers and details and tones, for me, it engages and relaxes the mind in the best possible way."

Chihei Hatakeyama

Blue Goat

LE054

Japan's Chihei Hatakeyama has been long known for gorgeous, drifting ambience that uncurls like smoke to reveal slowly changing shapes and textures weaving through each piece. He says Blue Goat is "influenced by the melody of Angelo Badalamenti, who I listened to when writing this piece."

Celer

For The Meantime

LE055

Recently cited in Resident Advisor by influential writer Simon Reynolds as producing some of the modern era's best ambient and new age music, Celer's Will Long is no stranger to massive works playing on temporality through sound.

"The idea of change is ever-present… for the meantime, let's pretend we can keep this moment forever."

Michael Vincent Waller

A Song

LE056

The understated work of Michael Vincent Waller becomes a thing of minimalist beauty on his solo piano composition, "A Song." This lyrical, impressionistic work explores the subtle gravity of harmonies with an inward gaze.

"Deep listening can be understood as a state of mind, that facilitates a deeper awareness of sound, as with one's experiential involvement with musical listening."

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

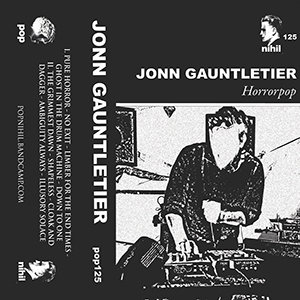

From a quick glance at the cover of this album, it would seem that Jonn Gauntletier (half of Pass/ages and a third of the defunct Ars Phoenix) had delved in the world of power electronics. The blown out, high contrast pic of him (in color on the CD version), mic in hand, leaning over a table of electronic gear gives off these vibes, but that is completely incorrect. Instead, the title Horrorpop is the true indicator, being an album of songs that blur the lines between horror movie ambience/soundtrack and straight ahead synth pop. Considering how well he navigates the two genres without falling into cliché (I would not describe any of these as being "synthwave" nor blatant John Carpenter emulation), the final product is one of excellent depth and complexity, but propelled by infectious rhythms and brilliant melodies.

From a quick glance at the cover of this album, it would seem that Jonn Gauntletier (half of Pass/ages and a third of the defunct Ars Phoenix) had delved in the world of power electronics. The blown out, high contrast pic of him (in color on the CD version), mic in hand, leaning over a table of electronic gear gives off these vibes, but that is completely incorrect. Instead, the title Horrorpop is the true indicator, being an album of songs that blur the lines between horror movie ambience/soundtrack and straight ahead synth pop. Considering how well he navigates the two genres without falling into cliché (I would not describe any of these as being "synthwave" nor blatant John Carpenter emulation), the final product is one of excellent depth and complexity, but propelled by infectious rhythms and brilliant melodies.

I have always appreciated in all of Gauntletier's projects how he brings in just the right amount of grime to his otherwise intricate productions, making for an amazing sense of depth while never becoming too polished or unnatural.That was true for Ars Phoenix, for Pass/Ages, and certainly here.Right from the onset of opener "Pure Horror" this is true:ghostly, decrepit loops are paired with bass passages to give a raw, slightly noise tinged sensibility, before he carefully fleshes the song out with a rigid drum machine, ghostly synths, and heavily echoed vocals.

He works from a similar template on "No Exit," initially a blend of nuanced synth sequences peppered with distorted, buzzing surges of sound to disrupt everything effortlessly.It builds into a slow lurch, with up front vocals and a mix that balances the noisy with the poppy, before eventually solidifying into a more straight ahead synth pop approach.On "The Grimmest Dawn" he continues that slow trudge approach, melded with droning foghorn electronics and bleak, shimmering layers.His clean, up front Bass VI playing is what keeps everything on a pleasantly melodic track that is only enhanced by the darker moments.

At times on Horrorpop, some influences (either directly or indirectly) begin to emerge.I felt some definite hints of early period Skinny Puppy throughout "Cloak and Dagger" via the percolating synths, snappy drum programming, and the heavy reverb and processing on Gauntetier's vocals just solidified this.The pulsating acid synths and 4/4 thump of "Limber For the End Times" molded into a catchy pop song on the surface but dark and dense below clearly called to mind some 1980s EBM works.For "Ghosts in the Drum Machine," the synth pop elements are at the forefront, complete with stiff drum machines and the DX7 Tubular Bell preset.Add in some catchy leads and lyrics about surveillance and (reasonable) paranoia, and there are clearly traces of Virgin era Cabaret Voltaire to be heard.

With both Ars Phoenix and Pass/Ages, Jonn Gauntletier has proven himself to expertly weave memorable pop songs out of bleak electronics and morose guitar work, and that continues to be the case on this tape.The horror part of Horrorpop is what gives this work a distinct quality in comparison, and that sinister sheen throughout is worked in skillfully.Stripped of the sequences, beats, and guitar work, there is a hell of a dark ambient record to be had, but by adding in the pop half of the album’s title, he ends up responsible for a perfect balance of bleak and catchy from start to finish.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

As far as I am concerned, any new release from Roly Porter is a noteworthy event, as he is absolutely not an artist who does anything by half measures. From his bold conceptual themes right down to every single aspect of sound design, each Porter full-length is a masterfully crafted and viscerally heavy statement unlike anything else. For this latest opus, Porter drew inspiration from the ancient burial tombs scattered across the moorlands of southwestern England, envisioning them as a sort of "mirror, or gate in time." In keeping with that fluid vision of time, Kistvaen achieves a distinctive marriage of timeless folk music traditions and cutting-edge production wizardry. While Porter occasionally errs too much on the side of portentous ambient gloom for my liking, Kistvaen reaches some rapturously sublime heights when he focuses on chopping and manipulating the vocals of his talented collaborators.

As far as I am concerned, any new release from Roly Porter is a noteworthy event, as he is absolutely not an artist who does anything by half measures. From his bold conceptual themes right down to every single aspect of sound design, each Porter full-length is a masterfully crafted and viscerally heavy statement unlike anything else. For this latest opus, Porter drew inspiration from the ancient burial tombs scattered across the moorlands of southwestern England, envisioning them as a sort of "mirror, or gate in time." In keeping with that fluid vision of time, Kistvaen achieves a distinctive marriage of timeless folk music traditions and cutting-edge production wizardry. While Porter occasionally errs too much on the side of portentous ambient gloom for my liking, Kistvaen reaches some rapturously sublime heights when he focuses on chopping and manipulating the vocals of his talented collaborators.

First thing first: Kistvaen is very much a headphone album for a number of reasons.The main one, of course, lies in the vivid clarity of Porter's sound design: this album is a feast of wonderful sounds and it is very easy to miss all the best moments without sustained, focused attention.Almost as significant, however, is Porter's unusual approach to composition.With casual listening, only the climactic swells of chords stand out as significant, which is a shame because so much fascinating activity takes places in Kistvaen's depths and periphery.I am tempted to say that crafting strong melodies and rich harmonies is not where Porter's strengths lie, but it would be more accurate to say that he simply has other interests that tend to take precedence over that aspect of his work.When he puts his mind to it, he is capable of creating some absolutely gorgeous melodic passages, such as the swooning crescendo of vocal loops and warm pads at the heart of "An Open Door" or the smeared and churning string motif that opens the epic "Passage."While I am not sure how much of Porter’s subversion of traditional compositional structures is by design, it definitely seems like he is devoted primarily to conjuring up immersive and evocative scenes: sometimes those scenes closely resemble music and sometimes less so, yet Porter's vision is always a compelling one.The more musical pieces like "An Open Door" are admittedly the ones that make the strongest first impression, but they are not necessarily always the best pieces (though "An Open Door" is unquestionably an album highlight).

For the most part, however, Kistvaen feels a series of well-produced field recordings from an imagined past that is extremely prone to cataclysmic events.In the opening "Assembly," for example, vocalist Mary-Anne Roberts gives an anguished and sometimes ululating performance over a sparse backdrop of seismic cracks, scraping metal, and rumbling waves of sub bass.Eventually Porter allows some lush, droning chords to creep in, but the overall effect is akin to a devastated widow howling a lament as her burning village collapses around her.In fact, the entire album feels like a series of haunted and bleak vignettes capturing the aftermath of some disaster in an enigmatic, ancient dream world.There are also some glimpses of transcendent beauty lurking within that nightmare though, as the seething, grinding horror of the following "Burial" eventually gives way to a lovely coda of warm strings.Elsewhere, "An Open Door" is the strongest example of Porter's more nakedly beautiful side, as its mournful piano theme blossoms into a deliriously beautiful swirl of warm chord swells and fluttering vocal loops…before erupting into a crushing and intense final crescendo that sounds like the entire world is being ripped apart.Porter follows that feat by approximating a heaving and violent disturbance in the very fabric of reality ("Inflation Field"), then dives wholeheartedly into yet another apocalypse, as "Passage" calls to mind an ancient city being absolutely leveled by an erupting volcano.Curiously, there is a brief interlude in that piece that features an anachronistic, stumbling, and out-of-sync synth motif that resembles deconstructed techno.Even though Porter is now working on an incredibly vast and timeless scale, lingering vestiges of his rave past still find their way into his vision.

The album closes on a unexpectedly radiant note with the lush, elegiac chords of the title piece, though they are bit buffeted by snarls of harsher textures.Nevertheless, "Kistvaen" feels like a poetic ascension at the end of a very disturbing, sad, and bloody story.As with the occasional rave/sound system touches lurking through the album, the heavenly chords of "Kistvaen" feel like a poignant nod to actual moments from Porter's own life, as his daughter currently sings in a church choir.While I cannot say that Porter is especially seamless or subtle in incorporating such disparate influences into his vision, I definitely like that they are there, as they reveal some soul and heart at the core of what could otherwise be a hollow exercise in technical brilliance and pure imagination.Still, the latter are a huge part of Porter's appeal and Kistvaen captures him at the absolute peak of his powers: any imperfections or flashes of bombast seem irrelevant in the face of such a crushing and vivid tour de force.To use a deeply uncharacteristic sports metaphor, Roly Porter swings for the fences every goddamn time and it is absolutely glorious when he connects.

Notably, these pieces were originally created as part of a multimedia performance featuring accompanying images from artist Marcel Weber and that seems like the logical culmination of Porter’s vision: I have often thought that directors should be falling all over themselves to enlist him for soundtrack work, as he seems like he would be uniquely suited for unleashing a climactic sensory overload that would leave filmgoers reeling in their seats as the final credits rolled.I still believe that, of course, but I am delighted that Porter has decided to expand his own vision and apply his formidable firepower to that instead.I hope I someday manage to catch the full majesty of the Kistvaen experience live, but the decontextualized music is quite a memorably intense statement in its own right.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Explicitly paying homage to a titan of the 20th century avant-garde is always a risky undertaking, as it unavoidably invites daunting expectations and often unflattering comparisons. Occasionally, however, an artist will come up with a suitably ingenious and radical angle and something new emerges that is every bit as intriguing as its original inspiration. Happily, Aki Onda's first release for Recital Program is one of those rare revelations, as it documents a series of "séances" in which Nam June Paik's spirit may or may not have crept into a series of radio transmissions. While I am personally quite skeptical about supernatural matters, enigmatically manipulating and haunting the airwaves from beyond the grave does seem like something Paik would absolutely do if he had the chance. That said, Nam June's Spirit Was Speaking To Me is an endearingly bizarre album regardless of whether or not the spirit world was involved, transforming distortion and interference into hallucinatory noisescapes that feel like the bridge between the darkness of early industrial music and the gleeful experimentalism of the LAFMS.

Explicitly paying homage to a titan of the 20th century avant-garde is always a risky undertaking, as it unavoidably invites daunting expectations and often unflattering comparisons. Occasionally, however, an artist will come up with a suitably ingenious and radical angle and something new emerges that is every bit as intriguing as its original inspiration. Happily, Aki Onda's first release for Recital Program is one of those rare revelations, as it documents a series of "séances" in which Nam June Paik's spirit may or may not have crept into a series of radio transmissions. While I am personally quite skeptical about supernatural matters, enigmatically manipulating and haunting the airwaves from beyond the grave does seem like something Paik would absolutely do if he had the chance. That said, Nam June's Spirit Was Speaking To Me is an endearingly bizarre album regardless of whether or not the spirit world was involved, transforming distortion and interference into hallucinatory noisescapes that feel like the bridge between the darkness of early industrial music and the gleeful experimentalism of the LAFMS.

This project first began to take shape a decade ago, as Onda spent several days at Seoul's Nam June Paik Art Center back in 2010 for a series of performances.One night, while scanning through South Korean radio stations in his hotel room, Onda "stumbled upon what sounded like a submerged voice" and "began to record it in fascination."That first recording is the heart of this album, as the opening "Seoul" stretches out for over 20 minutes, while the remaining three pieces are considerably more modest in scope.According to Onda, all four pieces were recorded from the same radio "with almost no editing, save for some minimal slicing and mastering."If that is indeed true, "Seoul" captures quite a fascinating and otherworldly confluence of overlapping and distorted transmissions.Initially, there is indeed a voice speaking over a sputtering miasma of crackle, hiss, and buried saxophone melody, but the more abstract churning weirdness that follows is far more compelling than the opening.The meat of "Seoul" essentially feels like a manic and obsessively repeating loop that passes through various stages of corrosion and interference as it relentlessly surges forward.In fact, it arguably has the same dynamics as a live noise performance, as its structure is enveloped in climactic cascades of static at various points.While such moments imbue the piece with the illusion of a deliberate arc and an enticing sense that the whole thing could go off the rails at any second, the real beauty of the piece lies in the alien character of the sounds themselves: a rhythmic collision of frog-like chirping, shuffling pulses, and an ascending melodic fragment that seems damned to eternal repetition.Sometimes the veil of static pulls back to fleetingly make one sound especially prominent, but it never stops being an unstoppable juggernaut of submerged bloops and wobbly phantasms.

Onda's next channeling occurred two years later in Germany, documented here by the modestly brief "Köln."Unlike its mercilessly propulsive predecessor, "Köln" feels like seething electromagnetic storm that unexpectedly dissipates to reveal a charismatic Frenchman speaking over a tinkling piano motif.That interlude is very short-lived, however, as it soon gets subsumed by sputtering snatches of a news broadcast before ultimately resolving into a rhythmic outro of scrape-like sounds and hissing static.The following "Lewisberg," recorded two years later, opens with a news broadcast about medical marijuana over an insistent beep.Once the voice disappears, it feels very looping and mechanized, but there is a wonderful fleeting glimpse of something resembling a bittersweet xylophone melody.Overall, however, it mostly feels like a malfunctioning industrial machine that keeps alternately faltering and roaring back to life.Its final minute is especially vivid, as all of the static and the sputtering disruptions unexpectedly vanish to allow the shuddering machine rhythm to unfold in perfect clarity.The album's final piece ("Wroclaw" (2013)) departs from the linear chronological arc of the previous pieces, but it makes for an excellent closing statement.Much like "Lewisberg," it locks into a very machine-like rhythm, but this time the rhythm is centered upon a repeating screech.It is a very cool motif that again recalls a noise performance, as the pitch of the screech sometimes changes and a buzzing bass tone erratically manipulates the intensity.It also evokes the very '80s "fever dream" sensation of drifting off as the final TV broadcast of the night gives way to formless static, but enhances it with the feeling that some kind of demonic entity is tenaciously trying to emerge from the hissing blizzard of flickering pixels.

There is a throwaway line from an interview that has weirdly stuck with me for the last few months: a person mentioned that their first thought upon seeing the view from a mountain was "painting is bullshit."It was obviously meant to be snarky, but there is a kernel of truth to that sentiment, as it reminded me that beauty and mystery organically exist all around us and that it is futile to try to reproduce them in any kind of straightforward way (I have no beef at all with stylized interpretations, mind you).I may be able to artfully express my own emotions or thoughts, but it is safe to say that I will never manage to paint a sunset or an ocean scene that is as impressive as the real thing.That brings me to the beauty of both Onda's work and "Seoul" in particular, as he creates great art simply by egolessly framing and amplifying what already exists.The confluence of transmissions that Onda captured that night in Seoul was certainly strange and fascinating, but so is the fact that we are completely immersed in a chaos of soundless invisible waves that seamlessly carry complex information from a transmitter to their intended destination. That is, of course, something that I never otherwise think about, yet "Seoul" captures a rare moment in which those invisible forces fleetingly coalesced into a static phantom that felt almost physical and alive.Naturally, both chance and technology played a crucial role in that event, but it took an attentive listener (and a gifted editor) to recognize its inherent beauty and present it in a way that others could hear as well.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

About this release:

In 2010, after some lengthy debates about the role of the machine-generated pulse in the development of music, legendary composer and improvisor Bob Ostertag sent me a collection of recordings made with his Buchla 200E modular analog system and asked: "Would people dance to this? Could this be considered techno?" "Not really," I said. "But I could probably turn it into techno with a little work." It was only after completing the remixes and sending them to the Sandwell District label that I realized this was the birth of a new project, and gave it the name Rrose. Since then, I have completed 18 additional remixes spanning over 90 minutes, which I have assembled here as both a compilation and a continuous mix. These include two additional remixes of Bob Ostertag (using his 1977 piece "The Surgeon General" as source material) and two upcoming remixes (available in mixed form only), one for the French artist Electric Rescue, and the other for an upcoming release on Eaux by the Brooklyn-based artist Lori Napoleon aka Antenes.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-15390031-1590757796-5587.jpeg.jpg)

Ulla's recordings of phone conversations and wildlife diffuse into the most vaporous and unsettling ambient dub textures on the third in our Documenting Sound series, recorded over the last few weeks in Philadelphia and recalling Sam Kidel's Disruptive Muzak, DJ Lostboi’s ambient hymnals and Vladislav Delay’s Chain Reaction pearls.

Pieced together from airspun recordings made in Philadelphia during spring 2020, Inside Means Inside Me holds a subtle mirror to the new world's psychic ambiance of existential, slowburn dread. Prizing the sensitively insightful, lower case manner that made Ulla’s recent Tumbling Towards A Wall album so memorable, here the sound is more poignant, the dissociative flux used to perhaps more therapeutic effect for an ephemeral reading of the times.

In the first half, Ulla makes a subtly heartbreaking use of crackling phone calls and dub stabs, but embedded in the music's weft they take on an unsettling resolution that’s hard to place. On the flip, more entwined conversations snag in the breeze with location recordings and scudding hypnagogic washes with a signature low key movement that keep you feeling swaddled but uneasy until the end.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The Letdown from multi-instrumentalist William Ryan Fritch kicks off Lost Tribe Sound's new label series "Built Upon A Fearful Void." The series introduces fifteen new albums to the label's roster over the next year, five of which will come courtesy of Fritch, including a new release as his alter ego, Vieo Abiungo.

The Letdown is a record better identified by the vibe it creates rather than a particular genre or style. It's dirty, unapologetically loud and charmingly haphazard. It's the sort of self-educated, non-jazz record that critics of Moondog would have written off as impure. Frankly, we're good with that. The strength of the record lies not with any collegiate-level classification, but in its ability conjure moods that just feel good, are instantly familiar and invite a certain nostalgia. The gritty, noir side of it, brings to mind the old black and white detective stories. The jovial, 1920's romanticism, lends a bit of class and gives the sense that even though everything is falling to shit, we are going to power through it with a bit of song and dance.

Whatever one happens to take away from this album, The Letdown is meant to be fun, help the whisky burn just a bit less, and keep the blood flowing. Read into it too much and you might spoil it. Guaranteed it is unlike any Fritch record to date.

More information can be found here.

Read More