- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

A humble compendium of guitar music from across nine separate compilations & regional issues, including pieces from the Tu M'p3 web-series, the E • A • D • G • B • E disc on 12k (along with an earlier, shorter version of the same), the 2nd Early Monolith business-card disc on Twisted Knister (available briefly in a cigarette vending machine in Bremen ca. 2005), the Brainwaves compilation on Brainwashed, the I Don't Think The Dirt Belongs To The Grass boxed set on Carbon, the Idioscapes on Idiosyncratics (plus a completely different alternate take), an unrealized Bodies of Water Arts & Crafts fundraiser-set, the Fabrique disc on Room40 (plus an alternate, separate piece recorded at the same time, never issued), and finally the Beaterblocker #2 compilation.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I was legitimately blindsided by Clarice Jensen's wonderful 2018 debut (For This From That Will Be Filled), but it left me with absolutely no idea what to expect from her in the future, as it was an unusual collection consisting of a collaboration, an ambitious solo composition, and a piece composed by Michael Harrison. As such, it was hard to tell if Jensen was a brilliant cellist with great taste, an extremely promising composer, or both. With the spellbinding The Experience of Repetition as Death, Jensen definitively confirms that she is indeed both, as she ingeniously employs loops and effects to craft a beguiling, varied, and richly textured five-song suite inspired by personal tragedy, Freud, and Adrienne Rich. Though death is a definite and deliberate theme, Jensen transforms it into something sublime, transcendent, and achingly beautiful. Moreover, the album's mesmerizing centerpiece ("Holy Mother") completely decimates any preexisting conceptions I had regarding what one person can achieve with a cello.

I was legitimately blindsided by Clarice Jensen's wonderful 2018 debut (For This From That Will Be Filled), but it left me with absolutely no idea what to expect from her in the future, as it was an unusual collection consisting of a collaboration, an ambitious solo composition, and a piece composed by Michael Harrison. As such, it was hard to tell if Jensen was a brilliant cellist with great taste, an extremely promising composer, or both. With the spellbinding The Experience of Repetition as Death, Jensen definitively confirms that she is indeed both, as she ingeniously employs loops and effects to craft a beguiling, varied, and richly textured five-song suite inspired by personal tragedy, Freud, and Adrienne Rich. Though death is a definite and deliberate theme, Jensen transforms it into something sublime, transcendent, and achingly beautiful. Moreover, the album's mesmerizing centerpiece ("Holy Mother") completely decimates any preexisting conceptions I had regarding what one person can achieve with a cello.

The title of this album is lovingly borrowed from Adrienne Rich's "A Valediction Forbidding Mourning," as Jensen has a deep admiration for Rich and her work and that particular poem holds deep personal meaning for her.However, it was actually Freud's writings about the death drive that indirectly led to the unusual conceptual framework of this album, as Jensen was fascinated by his thoughts about the "compulsion to repeat self-destructive behaviors or re-live traumatic events."Unsurprisingly, that got Jensen thinking a lot about how to break out of the repetitive nature of our existence.Needless to say, it is not hard to see how such thoughts might have immediate practical applications for an artist whose work is largely loop-based by necessity.In essence, Jensen set out to disrupt and transcend familiar patterns in order to subvert a creative death drive (or, at least, a creative stagnation drive).The most immediately graspable and overt evidence of Jensen's clever escape from the prison of repetition lies in the album's gorgeous bookends: "Daily" and "Final."In the opening "Daily," a warmly melodic cello theme languorously unfolds over a bed of drones, gradually blossoming into a more complex crescendo of overlapping loops.It all feels quite seamless and sensuous, yet the theme is actually "fragmented into three different tape loops and never expressed fully in order."On the closing "Final," those same loops are revisited in degraded and disrupted form until they are finally allowed to converge into a rapturous finale in which four separate loops unite in achingly lovely harmony.

While both of those pieces are absolutely gorgeous, the three pieces that lie between them offer a more varied array of pleasures.Notably, the first of the trio ("Day Tonight") is yet another variation on the same loops used in "Daily" and "Final," albeit an unrecognizably extreme one.According to Jensen, the theme is presented in an "unfamiliar key," but it also seems like it has been time-stretched until it is essentially a drone piece (it is twice as long as the other two pieces made from the same material).Eventually, however, it builds to a half-fluttering/half-stammering crescendo of sorts that calls to mind classic minimalism à la Steve Reich.The following "Metastable" is yet another drone-based piece, but it coheres into a bass-heavy and queasily see-sawing pulse of organ-like chords that were inspired by the omnipresent rhythmic beeping of hospital wards.It is interesting both rhythmically and texturally, but it does not have enough of a melodic or harmonic component to leave a deep impression.That is not true of "Holy Mother," however, which resembles nothing less than a roiling, endlessly shifting, and downright apocalyptic organ mass.While intermittent surges of rumbling low-end admittedly imbue the piece with a seismic intensity, Jensen nevertheless pulls off a nimble balancing act between light and darkness, as the organ-like tones dance and flicker like sunlight through a stained glass window.Aside from being a visceral tour de force, "Holy Mother" is quite striking in how dramatically Jensen is able to alter the sound of her cello, as she employs an array of effects to alternately transform her bowed strings into a glimmering nimbus of overtones and a mass chorus of deep voices.She also pulls off a neat trick at the end where the attack disappears to leave only the spectral reverberations (which then disappear as well to leave behind a wake of shivering feedback or overtones).

I suppose the only thing preventing me from declaring that The Experience of Repetition in Death is a start-to-finish masterpiece is the fact that the more experimental pieces ("Day to Night" and "Metastable") feel like a bit of an extended lull compared to the more melodic and emotionally resonant pieces that come before and after.It seems crazy to lament the fact that the album is not an uninterrupted parade of career-defining triumphs though, as three brilliant pieces out of five is more than enough to make me fall completely in love with this album: the high points are extremely high indeed.Unsurprisingly, it was the intensity and bold vision of the epic "Holy Mother" that first grabbed (and held) my attention, but after listening to the album on headphones a few times, I became convinced that "Daily" and "Final" are Jensen's most towering achievements to date.Both pieces are an absolute master class in both composition and performance, as each is warm, poignant, and beautifully melodic on their face and both make masterful use of looping.With closer listening, however, they reveal themselves to be significantly more than they first appear, as the elegant interplay of the loops and the shimmering accumulation of quivering overtones in their wake reach a level of sublime brilliance that I rarely, if ever, encounter (despite some very diligent searching on my part).With those two pieces, Jensen masks the complex within the simple and makes it all seem effortless and perfectly natural.To my ears, those thirteen minutes alone are more than enough to ensure that The Experience of Repetition in Death will be one of the albums that leaves the deepest and most long-lasting impact on me this year.Clarice Jensen is one seriously formidable artist.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This latest release from Félicia Atkinson is ostensibly a minor and somewhat transitional one, as it is a cassette intended as a sort of culminating document of a year spent traveling and performing. As with all recent Atkinson releases, however, the reality is far more complex, enigmatic, and deeply conceptual than anything that can be easily summarized in just one sentence. Partly inspired by the paintings of Helen Frankenthaler and partly intended as "a reassessed document of public performance with improvised studio interventions acting to break the linear stream of the live-on-stage temporality," Everything Evaporate is an intriguing and sophisticated release that seems to exist at the borderline of form and dreamlike abstraction. As such, it is not the optimal entry point for the curious (that would be 2019's The Flower and the Vessel), but deep listening reveals this release to be every bit as absorbing as the rest of Atkinson's recent hot streak.

This latest release from Félicia Atkinson is ostensibly a minor and somewhat transitional one, as it is a cassette intended as a sort of culminating document of a year spent traveling and performing. As with all recent Atkinson releases, however, the reality is far more complex, enigmatic, and deeply conceptual than anything that can be easily summarized in just one sentence. Partly inspired by the paintings of Helen Frankenthaler and partly intended as "a reassessed document of public performance with improvised studio interventions acting to break the linear stream of the live-on-stage temporality," Everything Evaporate is an intriguing and sophisticated release that seems to exist at the borderline of form and dreamlike abstraction. As such, it is not the optimal entry point for the curious (that would be 2019's The Flower and the Vessel), but deep listening reveals this release to be every bit as absorbing as the rest of Atkinson's recent hot streak.

For the most part, Everything Evaporate is an remarkably apt title for this release, as several of these songs sound like they are heeding that command in real-time.On the opening title piece, however, Atkinson largely picks up exactly where she left off with The Flower and the Vessel.Granted, it is a bit more minimal than usual, as Atkinson's breathy monologue unfolds over an oscillating and gently heaving bed of droning bass tones.Her seductively accented voice remains sharply in focus though, so the heart of the piece is an mysterious, poetic, and evocative spoken word performance.At this stage in her career, Atkinson’s ASMR-influenced narratives are very much the strongest and most instantly recognizable feature of her work, as she manages to make even mundane phrases like "can I get a cup of coffee please?" seem pregnant with deep hidden meaning.While her voice is unquestionably the center of everything, however, there are plenty of unpredictable other factors driving and shaping Atkinson’s recent work, as she seems to draw a significant amount of inspiration from both literature and visual art.And, of course, those "outside" influences rarely manifest themselves in expected or conventional ways.The following instrumental "I can't stop thinking about it" is a prime example of how those disparate threads converge, as Atkinson conjures up a surreal miasma of plinking marimbas, chirping birds, and spectral drones. At first, it all feels like a lazily clinking, disjointed, and formless haze, but the drones sneakily increase in richness and intensity for a shimmering and dreamlike crescendo.Notably, that piece also contains an excerpted fragment of a Helen Frankenthaler interview that recounts how she ruined a painting by messing with its fragile ambiguity.While that recording makes up a very small part of the album, its sentiment seems to be the guiding force at the heart of Everything Evaporate.I suspect Atkinson was being quite sincere when she titled the piece "I can't stop thinking about it."

The next piece, "Transparent, in movement," continues to explore that same hazy, impressionistic, and erratically plinking aesthetic, but Atkinson's voice returns for another cryptic monologue and the piece gradually converges into a slow, stumbling rhythm of sorts.Naturally, that alone is enough to make it a stronger piece.However, that is arguably just the piece's backbone, as a hallucinatory swirl of peripheral sounds blossoms outwards as the piece progresses towards an eerie finale of darkly twinkling piano.The following "Don't Assume" opens as yet another spectral haze of blurred drones and disjointed marimba plinks, but they are bolstered by an ascending roar of more visceral, metallic tones this time around.The piece admittedly takes a while to catch fire, yet it is worth the wait, as it eventually opens up into a genuinely creepy crescendo of overlapping, pitch-shifted voices and snatches of sinister-sounding sing-song melody.It feels like I am eavesdropping on a group of dead-eyed, possessed children joining together for either an occult incantation or a distracted performance of a macabre nursery rhyme.That late-album descent into darker territory continues into the closing (and ominously titled) "This is the gate," as an insistent harp-like chord obsessively repeats over a phantasmagoric mélange of floating feedback-like tones and murky smears of metallic chimes.Gradually, form emerges as rippling piano arpeggios overlap and the underlying metallic shimmer converges into a loose pulse of sorts.By the final moments, it actually blossoms into something quite beautiful as Atkinson's buried voice murmurs beneath some tender, lingering chords and a warm, all-enveloping hiss.

Those final two pieces are my favorite ones on the album and rank among some of Atkinson's finest work, particularly "Don't Assume."That said, "This is the gate" is probably Everything Evaporate's most radical creative breakthrough—or at least the most successful incarnation of the aesthetic evolution that runs throughout much of the album.More than any other piece, "This is the gate" evokes an absorbing and gently hallucinatory state of suspended animation, as Atkinson creates the illusion that all of the instrumentation is floating, decontextualized, and untethered to any structure.Then, she begins subtly sliding each piece into place until her lazily lingering tones converge into a warm web of rippling harmonies engulfed in a comforting sea of hiss.That is not a far cry from what happens elsewhere on the album, however, as the biggest difference is only that other songs achieve a similar sleight of hand by transforming disjointed percussive instruments into richly layered drones.As a result, Everything Evaporate is an especially rewarding album for focused listening, as it is a delight to hear Atkinson pull metaphorical rabbit after rabbit out of her hat, subtly and surreptitiously transforming her hyper-minimal palette of misused marimbas and a voice into pieces of impressive depth and mystery.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Beatriz Ferreyra, former pupil of Gorgy Ligeti, is an experimental music composer with many distinguished accolades. An academic who has published notable papers, she now works as a free composer taking commissions for concerts, festivals, ballets, and films. On Echos+, we hear her in peak form crafting intriguing and unique experiments in vocal manipulation. She uses the voice as base material for stereo-shifting computer music creations that arrest and delight.

Beatriz Ferreyra, former pupil of Gorgy Ligeti, is an experimental music composer with many distinguished accolades. An academic who has published notable papers, she now works as a free composer taking commissions for concerts, festivals, ballets, and films. On Echos+, we hear her in peak form crafting intriguing and unique experiments in vocal manipulation. She uses the voice as base material for stereo-shifting computer music creations that arrest and delight.

Room 40

The album is split into three pieces that are entirely different in character. The first piece, "Echos,"is a wildly inventive chorus of sampled vocalizations and spoken phrases, drawn together in a patch quilt symphony built entirely of the human voice. This is not just a simple stringing together of voice recordings like Christmas lights; it is an incredibly dynamic nine minute song with sudden stops and crescendos and palpable vibrancy. Words fail to describe the surprising results, a meticulously built, sonorous joy to listen to.

The second piece, "L'autre ... ou le chant des Marecages," where the word chant could be translated as 'song' but actually more accurately describes the piece when translated as the cognate 'chant.' It opens with strong imagery of Gregorian chant, then takes a turn for the more mysterious with sound manipulations that evoke horror and alarm. Again, the principal texture here is the human voice.

The third and final piece, "L'autre rive," apparently departs from vocal sample as instrument, though it is difficult to tell what the source samples are for these electronic machinations. Full of action and punch, it does not rest long on an idea. Percussion adds a strong element of drama, making this conclusion feel like a film score for the jungle.

Echos+ is a masterwork of a composer who is well versed in her tools and patient enough to imbue her creation with unlimited subtlety and detail, and I have thoroughly enjoyed it.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

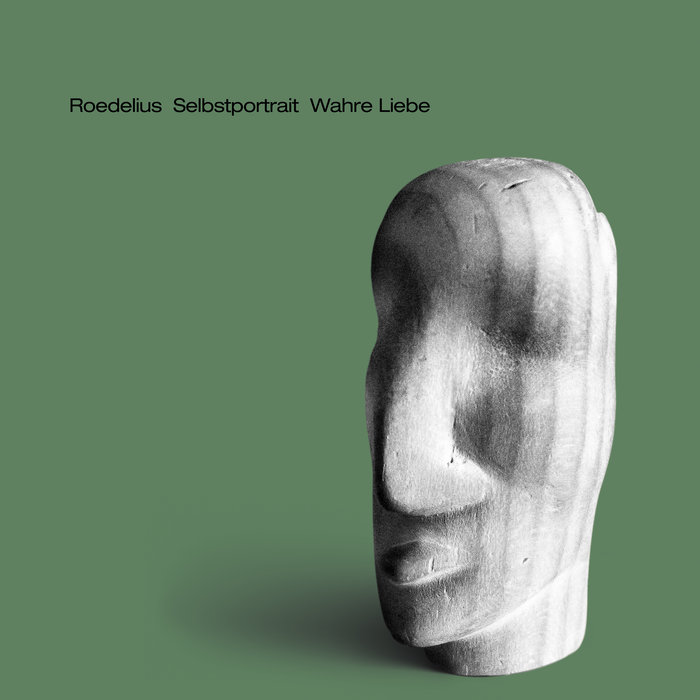

Hans-Joachim Roedelius is better known for his work as a founding member of the bands Cluster and Harmonia, both household names for fans of 1970s krautrock. This solo album, Selbstportrait Wahre Liebe, feels like a more clinical approach to krautrock, with all of the difference and repetition and none of the bombast. Filled with stately electronic keyboards and synthesizers, this minimalist document has the hair-raising effect of a calm, deliberate tea ceremony.

Hans-Joachim Roedelius is better known for his work as a founding member of the bands Cluster and Harmonia, both household names for fans of 1970s krautrock. This solo album, Selbstportrait Wahre Liebe, feels like a more clinical approach to krautrock, with all of the difference and repetition and none of the bombast. Filled with stately electronic keyboards and synthesizers, this minimalist document has the hair-raising effect of a calm, deliberate tea ceremony.

Bureau B

The opening piece, "Spiel im Wind," is a shifting kaleidoscope of small repetitive figures, like an avant-garde song in the round. "Wahre Liebe," translation "true love," is a piano led piece that unfolds like a poem, in a meandering stream of thoughts both beautiful and unsettling. "Winterlicht," loosens the formalism of earlier tracks and explores a duet like an open conversation, with pauses for contemplation. "Nahwärme" has many layers of sound, with the principal piano voices subsumed by ambience that lifts the curtains to let the sunshine in. "Gerne" conjures the spirit of Steve Reich with its propulsion in repetition, and interlocking pieces moving like the gears on a steam engine.

The tone remains consistent throughout the album. It is engaging enough to place full attention on while still having the quietude of a soundtrack to a slideshow film. Fans of krautrock, minimalist composition, and even some post rock will find this album engrossing.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Euzebio is Robert Piotrowicz's first record of solely modular synthesis after a period of working within different contexts. The recent Crackfinder was a collaboration with Jérôme Noetinger and Anna Zaradny, and Walser was a film soundtrack, so there has not been a "pure" Piotrowicz record for a while. It is obvious, however, that he has not lost his way when it comes to his preferred instrument. Again he coaxes some of the most varied sounds yet from his bank of electronics (in this case Buchla and EMS synthesizers), and focuses not just on the noisier characteristics of his previous works, but also some more traditional, rhythmic structures to vary things nicely.

Euzebio is Robert Piotrowicz's first record of solely modular synthesis after a period of working within different contexts. The recent Crackfinder was a collaboration with Jérôme Noetinger and Anna Zaradny, and Walser was a film soundtrack, so there has not been a "pure" Piotrowicz record for a while. It is obvious, however, that he has not lost his way when it comes to his preferred instrument. Again he coaxes some of the most varied sounds yet from his bank of electronics (in this case Buchla and EMS synthesizers), and focuses not just on the noisier characteristics of his previous works, but also some more traditional, rhythmic structures to vary things nicely.

Like a lot of work centered on modular synthesizers, there is an extremely kinetic feel throughout all five compositions on this record, but even with all the chaos, there is a distinct sense of composition and structure."Euzo Found Guitar," for example, is a swerving ball of inorganic guitar sounds and dramatic, synthetic string scrapes for its opening, complex and multilayered.However, it is not long before he shifts things to a rhythmic, almost skeletal techno sound before closing things up on a tense, forceful note.

The same hints at traditional structure can be heard on "Elektros Spong" as well.Opening with an amazing approximation of pummeling drum sounds, Piotrowicz injects an array of jerky, erratic synth sequences that on the surface sound like pure entropy, but instead reveal a multitude of organized, interlocking sections.He transitions from heavy to skittering drum sounds and low bit rate synth layers before closing things out on a satisfyingly disjointed note.He utilizes a bit of everything on "To Fleh," opening from sputtering laser beams and big dramatic synth swells into faux birdcalls and chiming bells.In many ways it reflects his soundtrack work, as there are all the big, dramatic stings of an action movie trailer, but far too varied and nuanced to work in that capacity.

Intensity largely reigns supreme throughout Euzebio, but there are of course moments where the album relents.There may be some wet synth thuds throughout "Flares Et Wasser Hole," but resonant bell tones and carefully constructed melodic fragments are more at the forefront.Closing piece "Ocarina Wars" makes for the perfect conclusion to the record.Opening with a dense wall of malfunctioning 1970s computer mainframes, he throws in a healthy selection of laser bursts and mangled synth leads.There is also the occasional synth thud that, the way it is used, could almost herald the opening of a thumping techno track, but he never allows it to get off the ground.

Even when Robert Piotrowicz was deep in purely synth records, he always had a knack for balancing the unpredictability of what miles of patch cables can do with a composer’s sense of construction and dynamics.It would seem his collaborations and soundtrack work have further influenced him, because the hints of music and film score bombast are prevalent here, but nicely subsumed into his own repertoire.I have never found a dull moment in Piotrowicz’s catalog, but Euzebio is certainly a new high water mark for his work.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The start of the album made me think of what my grandmother would have said: "What is this twaddle?" and "Is this what you call music?" White is foremost a drummer, first founding Dirty Three with Warren Ellis and Mick Turner, and with bands as varied as Cat Power, PJ Harvey, and The Blackeyed Susans. Conversely, Marisa Anderson is a classically trained master of melancholic guitar rooted in American folk, neo-classical and African guitar styles, with an early foundation in country, jazz and even circus bands. With musicians as these at the helm, this becomes perfect jam music; not jam as in "jam band" or Grateful Dead, but a rich psychedelic tapestry woven by practiced hands that take pleasure in breaking the rules of jazz foundations and serve to transport the listener to new heights.

The start of the album made me think of what my grandmother would have said: "What is this twaddle?" and "Is this what you call music?" White is foremost a drummer, first founding Dirty Three with Warren Ellis and Mick Turner, and with bands as varied as Cat Power, PJ Harvey, and The Blackeyed Susans. Conversely, Marisa Anderson is a classically trained master of melancholic guitar rooted in American folk, neo-classical and African guitar styles, with an early foundation in country, jazz and even circus bands. With musicians as these at the helm, this becomes perfect jam music; not jam as in "jam band" or Grateful Dead, but a rich psychedelic tapestry woven by practiced hands that take pleasure in breaking the rules of jazz foundations and serve to transport the listener to new heights.

There’s a lot going on with each musician bringing much to the table. It kicks off sounding like noise, chaotic and disjointed to the untrained ear, and it is, but there’s a pining melody on this first track that holds it together if you listen. Push through, because once past the first track, it leads to a complex, but rich and transcendental experience. I come from a familiarity with Jim White as part of Xylouris White with Cretan lute player Giorgos Xylouris, a duo who blend Greek folk into Avantgarde rock with an abandon of free jazz. White brings it here as well, incorporating modern and ancient drums to Anderson’s melancholic guitar.

As background music, it may sound like each musician has their own agenda, but a careful listen reveals the mastery of each musician being able to hold their own agenda, reining it in, blending with each other, and smoothly taking back the reins to reveal the uniqueness and strength of each musician on their own chosen instrument. "The Other Christmas Song" is a perfect example of this. "The Lucky" showcases the skill of each musician, bringing out the best in both.

As a self-professed fantasy geek, the title immediately suggests the event in The Highlander films in which an immortal warrior beheads his opponent and a surge of energy from the deceased occurs. The victor then experiences "The Quickening," absorbing all the power and knowledge the opponent had obtained in life. The play between the two musicians hints at a powerful collaboration, less a competition, as if the two have sought to teach and learn from each other, working to form a tightly knit bond such as to be one mind. With no words to get in the way, you can make your own imaginary film to this as the music gets in your head and your mind starts to wander, creating stories from the soundtrack that is provided by White and Anderson.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Oud, Lute, acoustic guitar, or lap steel guitar? While my musical knowledge is varied, my ear is not trained to pick out the many instruments used or mimicked by Bishop. He makes guitars sound like any of these aforementioned instruments, at any point in time, with practiced fingers and the equivalent musical knowledge of a library with every note he plays, a master guitarist proficient in a variety of guitar techniques and knowledge of music traditions. His latest album excels in his freer use of experimentation with theme and electronics, crafting a "dream pharmacy" as the title implies.

Oud, Lute, acoustic guitar, or lap steel guitar? While my musical knowledge is varied, my ear is not trained to pick out the many instruments used or mimicked by Bishop. He makes guitars sound like any of these aforementioned instruments, at any point in time, with practiced fingers and the equivalent musical knowledge of a library with every note he plays, a master guitarist proficient in a variety of guitar techniques and knowledge of music traditions. His latest album excels in his freer use of experimentation with theme and electronics, crafting a "dream pharmacy" as the title implies.

His previous releases have been focused on exploration of a particular genre. The Freak of Araby was a carefully crafted homage to late Egyptian guitarist Omar Khorshid, while the tracks on Tangier Sessions explored the sounds of a C. Bruno guitar from the 19th century that Bishop purchased in Morocco. For Oneiric Formulary, he further expands his already impressive repertoire of styles (Indian Raga, flamenco, surf, baroque, and many others) to craft an "oneiric" feel throughout. He takes turns adding unlikely sounds in the way of electronics that hum behind acoustic guitar, switching to near pop-embellished tunefulness, then leads the listener into nightmare visions in the very next track. Bits of drone experimentation are strewn throughout and unique synthesized sounds diverge from the usual guitar fare.

One such example of Bishop straying from his guitar is found on the opening tracks, "Call to Order." The shortest track of the batch, it kicks off the album with a mild nightmarish feel, or if you'd prefer, David Lynchian dreams, provided by an alien, synthesized theremin. "Celerity" goes back into more familiar territory and showcases Bishop's practiced dexterity, while "Mit's Linctus Codeine Co." sounds like an imaginary soundtrack to a film an alien cantina, or hold music at your local small town grocery store. "Renaissance Nod" is precisely that, a nod to what you might hear a minstrel playing at a Renaissance Faire. It isn't until "Graveyard Wanderers" that Bishop fully takes us into Tim Burton electronic territory, creating an auditory backdrop of rattling chains, dripping water and tortured souls, all of which may or may not have guitar as their original foundation.

"Dust Devils" is a catchy tune reminiscent of bagpipers in the Scottish highlands backed by tabla or djembe. The immediate standout track is "Enville," a pleasant acoustic track worthy of everyone's ears, one of his most melodic and memorable to date, that showcases his obviously practiced fingerpicking. "Black Sara" reminds me of a Spanish film. "The Coming of the Rats" is a wonderful interplay of electric and acoustic guitar, with acoustic guitar forming the baseline, and the electric guitar adding complexity, and seems to tell a story. Closing track "Vellum" concludes the album with a waltzy feel with scattered time signatures.

Dreams don't always make sense. They are not always logical, and can jump from storyline to storyline. Much is the same with this album, and Bishop is always mindful of the varied nature dreams can take. It is a journey of pleasant valleys, dangerous peaks and subterranean nightmares, all on the same album.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I know very little about Nicole Oberle and I suspect that suits her just fine, as she self-describes as a "digital recluse." What I do know is that she is based in Texas and that she has recorded quite a prolific stream of self-released material over the last year or so. One of those releases was last fall's Skin EP, which has since been picked up and reissued in expanded form by Whited Sepulchre. That is great news for a couple of reasons, as I would not have encountered her work otherwise and this new incarnation of Skin is a significantly more substantial and compelling release than its predecessor. In fact, the newly added songs are some of my favorite ones on the album. As such, I suspect this incarnation of Skin will rightfully go a long way towards expanding Oberle's fanbase, as there are appealing shades of both Grouper and erstwhile labelmate Midwife lurking among these eleven songs. The most fascinating parts of the album, however, are the ones where those influences collide with Oberle's divergent interests in ghostly, downtempo R&B grooves and unsettling, diaristic sound collages.

I know very little about Nicole Oberle and I suspect that suits her just fine, as she self-describes as a "digital recluse." What I do know is that she is based in Texas and that she has recorded quite a prolific stream of self-released material over the last year or so. One of those releases was last fall's Skin EP, which has since been picked up and reissued in expanded form by Whited Sepulchre. That is great news for a couple of reasons, as I would not have encountered her work otherwise and this new incarnation of Skin is a significantly more substantial and compelling release than its predecessor. In fact, the newly added songs are some of my favorite ones on the album. As such, I suspect this incarnation of Skin will rightfully go a long way towards expanding Oberle's fanbase, as there are appealing shades of both Grouper and erstwhile labelmate Midwife lurking among these eleven songs. The most fascinating parts of the album, however, are the ones where those influences collide with Oberle's divergent interests in ghostly, downtempo R&B grooves and unsettling, diaristic sound collages.

The album opens in supremely creepy fashion, as the murky, brooding ambiance of "Shipyards" resembles a grainy and enigmatic video tape that that a serial killer might send to taunt the detectives on his trail.Granted, evil-sounding dark ambient drones are far from my favorite thing, but such an opening is extremely effective in setting a dread-soaked and nightmarish tone for the album.Also, Oberle does quite an effective job of further deepening the sinister atmosphere with distorted and mostly indecipherable bursts of speech.That said, I was both relieved and surprised when that oppressively dark and claustrophobic mood opened up into the warm and undulating dreamscape of "Self-Speak."Oberle's aesthetic is quite a varied, unpredictable, and evocative one, as all of the songs on Skin feel like they occupy the same shadowy, twilight state of hallucinatory semi-reality, yet they all seem to evoke very different scenes within that unsettling and hypnagogic world.In the following "Unnamed," for example, a lovely progression of piano arpeggios unfolds in a heavenly haze of chopped vocal fragments, cinematic string swells, and buried snatches of warbling psychedelia."Cold Metals," on the other hand, feels like a ghostly and deconstructed bit of gloomy pop that makes extremely effective use of a blurred vocal hook.That piece also highlights Oberle's unusual and intuitive feel for dynamics, as it unexpectedly gives way to a brief breakdown of ringing, subtly dissonant chords before the beat kicks back in for the final act.The final song from the original EP ("A Knot in Twos") is yet another spectral pop foray, calling to mind an instrumental outtake from Slowdive's Souvlaki before blossoming into a brief spoken word interlude that feels like a cryptic fragment of an overheard phone call.

The second half of the album, which is composed of entirely new material, opens with another teasing instrumental approximation of melancholy pop ("Cigarette Burns"), then segues into a surprisingly strong and seductive dive into spectral, soft-focus R&B ("Stay With Me").At only two minutes, "Stay With Me" is woefully brief, but it is the closest thing that the album has to a great single, as it calls to mind Tri-Angle's brief run of killer witch house acts like Holy Other.That piece is followed by a hazy, beat-driven interlude ("Tired of This") that abruptly cuts out to give way to the album's most sustained passage of poignant, eerie beauty: the one-two punch of "Nobody Knows" and "I'm Just Stuck."The two pieces segue together into what is essentially a single sound collage, but the character of the underlying music differentiates them, as the more melancholy first half transforms into something akin to heavenly (if fatalistic) beauty.The music mostly just provides coloration though, as the truly haunting heart of that diptych is the spoken word recording that runs across the two pieces, as it feels like the final voicemail left by a woman who is about to vanish forever.In fact, it is easily one of the most heartbreaking and unsettling passages that I have heard on any album this year.I cannot think of much that could follow such an emotional wallop and Oberle wisely does not try, opting instead to close the album with just a floating, bittersweet coda ("Separation"), granting me a few comparatively peaceful moments to process what I just heard before abruptly breaking the spell with the final click of a tape machine.

If Skin has a weakness, it is only that several pieces feel more like sketch-like vignettes than actual songs, but that may very well be intentional, as the album has the uncomfortably voyeuristic feel of flipping through the journal of a troubled friend.Or, put more poetically, it feels like a supernatural fog that occasionally parts enough to reveal fleeting, decontextualized glimpses of various eerie, mysterious, and disturbing scenes.Another notable aspect of Skin is that Oberle seems like she is being pulled in a number of different stylistic directions at once, which would normally be a real issue for me.However, she has an uncanny talent for weaving together seemingly disparate threads into an arc that feels organic and unforced.Very few artists can pull off such a feat.Aside from that, Oberle shows a real knack for small, unexpectedly poignant touches that give the album a beautifully raw and intimate feel, as Skin is filled with great textures and details like exhalations, lighter clicks, distressed and warbly voice recordings, and the audible starts and stops of a tape machine.All of those fragments combine into quite an impressively absorbing and emotionally resonant whole that is quietly heavy in a way that few other albums can match.I am not sure if this quite counts as a formal debut (Oberle has previously released a few physical tapes on her own), but it will be an incredibly strong contender for the best debut of the year if it does.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I was quite curious to see which direction Klara Lewis's latest album would take, as her previous solo releases were generally quite radical and hyper-constrained in their avoidance of anything resembling conventional instrumentation. While both Ett and Too are aptly described by Editions Mego as "eerie rhythmic variations," such a summary falls short in conveying the uniqueness of Lewis's vision, as it often felt like she was quixotically attempting to compose pop songs solely from murky field recordings and decontextualized fragments of beats and melodies. With Ingrid, however, Lewis makes a dramatic and unexpected aesthetic reversal, as she slowly transforms a haunting and melodic cello loop into a wonderfully gnarled and heaving longform piece.

I was quite curious to see which direction Klara Lewis's latest album would take, as her previous solo releases were generally quite radical and hyper-constrained in their avoidance of anything resembling conventional instrumentation. While both Ett and Too are aptly described by Editions Mego as "eerie rhythmic variations," such a summary falls short in conveying the uniqueness of Lewis's vision, as it often felt like she was quixotically attempting to compose pop songs solely from murky field recordings and decontextualized fragments of beats and melodies. With Ingrid, however, Lewis makes a dramatic and unexpected aesthetic reversal, as she slowly transforms a haunting and melodic cello loop into a wonderfully gnarled and heaving longform piece.

This album, a one-sided LP, is intriguingly billed as an improbable blend of William Basinski-style loop disintegrations and black metal intensity.In a general sense, I suppose Ingrid can reasonably be described as exactly that, but the similarity to Basinski's work lies primarily in Lewis's compositional technique rather than its tone.Great Basinski albums like El Camino Real and 92982 are extremely nuanced, tender, and dream-like affairs.Ingrid, on the other hand, evokes something considerably more raw and primal.In fact, it can reasonably be described as "nightmarish," though it definitely feels nightmarish in an arty Japanese horror film way rather than a "shrieking church-burners in face paint" way.Moreover, it maintains an earthy, physical foundation even as it becomes increasingly volcanic and frayed.In more practical terms, that means that Ingrid opens with a bittersweetly beautiful and emotionally resonant cello melody, but it soon becomes disconcertingly frozen in time, damned to repeat the same short melodic fragment for all eternity (or at least the duration of the album).While the initial melody is a poignant and sensual one, the "locked groove" moment isolates just a brief fragment of slow-motion, see-sawing melancholia and obsessively repeats it for the next nineteen minutes.

Admittedly, that frozen melody is quite a cool trick, but the meat of the album lies in how Lewis increasingly corrodes and distorts that fragment as the piece unfolds.At first, the transformation merely manifests itself as a quivering and shimmering haze that radiates outward from the dense and groaning string loop.I cannot tell exactly what Lewis is doing or how she is doing it, but it seems like the loop and its lingering hallucinatory nimbus begin to increasing feed back upon themselves, resulting in fluttering oscillations and occasional swells of sharper, more ringing tones.As that happens, the low end starts to gradually amass rumbling intensity as well, as each repetition of the loop feels like a more intense subterranean surge than the last.At a certain point, the central loop starts to feel like just one component in a much richer tapestry of layers, as it becomes increasingly subsumed by the roiling, distorted low end while the high-end shimmer coheres into something resembling a structured chord progression.Aside from that, the piece's rhythm transforms as well, as the gnarled, smoldering undercurrent of distortion lingers and lags enough to fall out of phase with the central theme's original pulse.Once it reaches its seismic crescendo, however, Lewis gradually allows the heaving elemental power of the low end to fade away, leaving behind an unexpectedly tender and lovely coda that almost feels like dreampop or shoegaze.

For the most part, I have absolutely nothing critical to say about Ingrid, as it is a flawless, hypnotic, and impressively relentless piece of music with a purposeful trajectory and an elegant symmetry.I even appreciate the unusual format, as it drives me crazy when people release longform pieces that require me to flip a record at some arbitrary midpoint.It is heartening that Lewis both acknowledged the limitations of the vinyl format and found a clever way around them (an important skill in this current period of vinyl supremacy).However, I will say that Lewis's earlier albums were objectively a bit more original and unlike anything anyone else was doing.That said, plenty of wildly inventive artists release disappointing albums because originality and execution are two separate things.My favorite artists tend to be those that manage to strike an optimal balance between bold ideas, vibrant production, and compositional craftsmanship and Lewis absolutely nails that trifecta with this album.

Given that, I feel fairly confident in stating that Ingrid is a major creative breakthrough for Lewis and possibly her best album to date as well.It is undeniably still a cerebral and conceptually interesting work, but those artier tendencies are a hell of a lot more effective when they are woven into a roiling tsunami of visceral power and emotional intensity.I suppose that might be where the metal influence most strongly manifests itself, as Lewis has blossomed into a formidable composer who has managed to extract the cool and dangerous elements of the genre without bringing along any of its flaws.The result is an experimental music album that sounds like it could beat me up, steal my girlfriend, and decimate a hotel room, which definitely has a stronger and broader appeal than any similar fare with a less favorable balance between the cerebral and the physical.

Samples can be found here.

(Note: the physical album has an official release date of May 1st, but the digital version is available now)

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

International sound art label Flaming Pines has collected 24 singles in the Tiny Portraits series to form this pay what you want compilation of music dedicated to overlooked places. Each artist was asked to examine a physical space or location, and create a portrait of that space using whatever mode of creative inquiry they have in their toolbox. As an album, the music veers through manifestations of sound, with peaks and contours that are mostly peaceful in character. The result is an evocative, varied collection, with each piece a startlingly unique contribution to the whole, to be enjoyed as part of a journey through physical reality.

International sound art label Flaming Pines has collected 24 singles in the Tiny Portraits series to form this pay what you want compilation of music dedicated to overlooked places. Each artist was asked to examine a physical space or location, and create a portrait of that space using whatever mode of creative inquiry they have in their toolbox. As an album, the music veers through manifestations of sound, with peaks and contours that are mostly peaceful in character. The result is an evocative, varied collection, with each piece a startlingly unique contribution to the whole, to be enjoyed as part of a journey through physical reality.

The elements of composition used are primarily field recordings, soundscapes, ambient effects, and embellishments from acoustic instruments and noise makers. The field recordings include found sounds, human, animal, and insect activity, birdsong, heavy machinery, radio, and the chatter and clatter of life in a modern city. Some of these pieces are abstract, evoking moods and emotions without the rigidity of structure. Others have a strong narrative arc to the piece, tracing the story from start to finish with more explicit musical elements.

Some of my favorites are "My Childhood Is My Only Home," a lounge ambient song with saxophone, keys, and meandering thoughts in jazz; "Andrejosta. Rudens Vilcieni (October sketches 2015)," a dark, slinky mishmash of upright bass and field samples, like the banging of grocery carts and emptying delivery trucks in a big box parking lot; "The Same Sun," field recordings from the streets of Cairo interrupted with chanting in unison, perhaps in prayer; and "Dean Clough C2," a beautiful flute and running water piece that calls to mind the compositions of Oliver Messiaen.

Tiny Portraits includes the work of composers from across the globe, as far as Australia, Canada, Latvia, Ukraine, Egypt, the UK, and more. While it bears the name of a complete compilation, it shares no overlap with the Tiny Portraits collection that Flaming Pines issued on CDR in 2013. These pieces have surfaced over the years since but all have been inspired by the same conceptual prompt. It's a wonderful way to experience some of these remote locations in this difficult point in time when travel is limited.

Read More