- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I am generally not someone who believes that everything happens for a reason or that tragedy breeds great art, but I do think that the emotionally fraught and unusual circumstances surrounding the creation of Red Sun Through Smoke steered Ian William Craig in a direction that feels uncannily appropriate for the current moment. Craig's original plan was simply to sequester himself for a couple weeks in his grandfather's empty house in Kelowna, British Columbia while he wrote and recorded a new album. As it turned out, however, fate had quite a macabre cavalcade of unpleasant surprises in store for him, as Kelowna became surrounded by forest fires, his grandfather died, his parents moved into the smoke-shrouded house, and the woman he loved moved to Paris. Naturally, all of those events resulted in quite an intense swirl of emotions, but at least a correspondingly intense (and beautiful) album ultimately emerged from that fraught period, as the best moments of Red Sun Through Smoke distill Craig’s art to its simplest, most direct, and most intimate form.

I am generally not someone who believes that everything happens for a reason or that tragedy breeds great art, but I do think that the emotionally fraught and unusual circumstances surrounding the creation of Red Sun Through Smoke steered Ian William Craig in a direction that feels uncannily appropriate for the current moment. Craig's original plan was simply to sequester himself for a couple weeks in his grandfather's empty house in Kelowna, British Columbia while he wrote and recorded a new album. As it turned out, however, fate had quite a macabre cavalcade of unpleasant surprises in store for him, as Kelowna became surrounded by forest fires, his grandfather died, his parents moved into the smoke-shrouded house, and the woman he loved moved to Paris. Naturally, all of those events resulted in quite an intense swirl of emotions, but at least a correspondingly intense (and beautiful) album ultimately emerged from that fraught period, as the best moments of Red Sun Through Smoke distill Craig’s art to its simplest, most direct, and most intimate form.

When I listened to this album for the first time, one of the thoughts that immediately struck me was how much Craig’s creative trajectory uncannily mirrors that of Grouper's Liz Harris: both artists initially established themselves by carving out a distinctive style, then set about slowly dissolving that stylistic veil to reduce their palette to little more than a voice and a piano.As someone who loves what Craig can do with his arsenal of wobbly, hissing tape players, I cannot say that I unambiguously prefer this more naked approach to songcraft, but I certainly admire and appreciate his desire to make his art more honest and distilled.That said, Craig's transformation is still a work in progress, so Red Sun Through Smoke strikes an effective balance between his experimental/abstract side and his more songcraft-driven side.Both sides yield some wonderful results, but it is definitely the unadorned and heartfelt piano ballads like "Weight" and "Stories" that feel like the album's true soul and raison d’être.Admittedly, I have not historically been thrilled when an experimentally minded musician that I love decides to sit down at a piano to try their hand at nakedly intimate balladry, as people tend to fall into extremely familiar patterns with that instrument.Much like harps and harmoniums, it is deceptively easy to make a piano sound good, but extremely difficult to find and establish a distinctive voice.To his credit, Craig solved that problem beautifully in "Weight" by playing in an organically loose and fluid way that is shaped by the central vocal melody.There is a chord progression, but Craig seems far more interested in the way the notes linger and dissolve in the wake of his vocal phrases than he does in creating a structured foundation to sing over.Also, the rhythm feels far more dependent upon Craig's own breathing patterns than it does with any unchanging time-signature.

As far as I am concerned, "Weight" stands as both the album’s achingly beautiful centerpiece and the culmination of Craig’s evolution as a composer, as it seamlessly merges tender, lilting melodies with hiss-ravaged harmonies in near-rapturous fashion.The following "Comma" is similarly lovely though, as Craig's voice nimbly swoops and slides around in the higher registers in a way that would make a soul/R&B diva proud.Also, the underlying music captures Craig at his most inventively minimalist and texturally effective, as frayed swells of harmonized vocals provide an unconventionally ghostly and warbling backdrop.Craig later repeats that delightful trick once more with "Take," but the remainder of the album is generally an impressively varied suite of songs and vignettes that take his hyper-constrained palette in some very interesting and divergent directions.Granted, some of those directions work much better than others, as I cannot say that I would miss the a capella opener "Random" or the piano instrumental "Mountains Astray," but the hit-to-miss ratio is nevertheless quite an impressive one overall. I am especially fond of two of the more tape loop-based pieces, particularly the scratchy, disjointed, and rippling arpeggio layers of "The Smokefallen."The darker and more spidery "Last of the Lantern Oil" is quite haunting as well, as fragments of Craig's vocals warble and flutter in a haze of decaying, distorted, and deconstructed minor key piano chords.

Notably, "Last of the Lantern Oil" features some noises from a shortwave radio that Craig remembers fondly from his late grandfather's days as a ham radio enthusiast.Those sounds are not a terribly crucial part of the piece, but their impact on Craig's art cannot be overstated, as he has observed that "all of the sounds inherent to that process, from the crackling static to the disembodied voices breaking up to the glissando of the frequency dial searching for connection, have directly informed what it is that I do."Craig's grandfather also deserves some credit for his decision to partially move away from that aesthetic, however, as Craig notes that his own interest in "themes of decay and forgetting" began to feel false as his grandfather increasingly deteriorated from dementia.I get that, but I personally hope that he continues dabbling with his decaying loops forever anyway, as that is what made me first fall in love with his work.I can certainly embrace Red Sun Through Smoke's more poignant balance of openness and emotional depth to abstraction and experimentation for now though.Moreover, I suspect that gradual transformation was not easy for Craig (given his reluctance to even sing on his early albums), but that unflinching and fearless examination of what he wants to say and how he needs to say it is precisely why he has blossomed into one of the most gifted artists of his generation.I would not necessarily call this album raw, as Craig was very exacting in shaping how these pieces sound, but there has been a significant decrease in the amount of artistic distance that he allows to creep into his work. In fact, Red Sun Through Smoke is quite literally a diaristic album (the lyrics were culled directly from Craig's journal) and it is all the better for it.While I could probably make a strong case that some of Craig’s other albums have more great songs, none of them have left a deeper mark, taken more chances, or made a stronger statement than this one.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This latest release from Jon Wesseltoft and Lasse Marhaug's long-running (if fitful) drone project was recorded all the way back in 2013, which makes for quite a perplexing mystery, as I cannot understand why such a great album would remain on the shelf for so many years (especially since Marhaug himself runs a label). Most likely, however, The Hex of Light was simply the victim of Marhaug's incredibly prolific output, as well as Mount Meru's tendency to bounce from label to label with every release. Also, it appears as though this project was either on hiatus or completely defunct for quite some time, though Wesseltoft and Marhaug have performed together in Meru-esque form as recently as 2016. Aside from that, it is probably also safe to say that Wesseltoft poured quite a lot of time into mastering and editing this monster, as The Hex of Light's two longform pieces represent crushingly dense and mind-melting drone heaviness at its absolute best.

This latest release from Jon Wesseltoft and Lasse Marhaug's long-running (if fitful) drone project was recorded all the way back in 2013, which makes for quite a perplexing mystery, as I cannot understand why such a great album would remain on the shelf for so many years (especially since Marhaug himself runs a label). Most likely, however, The Hex of Light was simply the victim of Marhaug's incredibly prolific output, as well as Mount Meru's tendency to bounce from label to label with every release. Also, it appears as though this project was either on hiatus or completely defunct for quite some time, though Wesseltoft and Marhaug have performed together in Meru-esque form as recently as 2016. Aside from that, it is probably also safe to say that Wesseltoft poured quite a lot of time into mastering and editing this monster, as The Hex of Light's two longform pieces represent crushingly dense and mind-melting drone heaviness at its absolute best.

This project first surfaced back in 2009 with an LP on Important Records (The Ocean of Milk) and has had quite a strange and confounding trajectory ever since, leaving behind just a small handful of limited physical releases documenting only a few short years of activity.As a result, it impossible for me to tell exactly how much the project has evolved since its beginning and I also have no idea if this release is a mere vault-clearing or a sign that Wesseltoft and Marhaug have rekindled their great partnership anew.I am naively hoping for the latter, as it is rare to find two artists so perfectly intertwined and single-mindedly focused on achieving something so nightmarishly monolithic (or succeeding so beautifully).Obviously, both artists are Norwegian and share long histories in extreme music, so it was inevitable that they would cross paths, but Mount Meru was born specifically from a shared desire to "explore their mutual interest in long-form music, psycho-acoustics, the phenomenology of sound, and its correlation to perception."Based on The Hex of Light, it is clear that the duo took that interest in psycho-acoustics very seriously, as it feels wildly misleading to describe this album as anything akin to a "drone album" in the conventional sense.Instead, drones are merely the structural framework that the pair use to unleash two truly harrowing slabs of squirming and buzzing heavy psych.

Of the two pieces, the opening "Foliage" is by far the most harrowing, as it instantly resembles an impossibly dense mass of infernal, hallucinatory crickets whose chirps smear and bleed together into a sickly, buzzing swirl.And in a broad sense, that is exactly where it lingers for the next nineteen minutes, as Wesseltoft and Marhaug seem perfectly content to maintain that unbroken, squirm-inducing tension and seem decidedly disinterested in providing any respite in the form of a chord change or convergence upon any non-dissonant harmonies.When it comes to the details, however, "Foliage" is a mesmerizingly rich, dynamic, and endlessly evolving piece, as new patterns of throbs, pulse, sweeps, and oscillations continually form and dissipate in the queasy maelstrom of sinister buzzing.That said, a gently undulating organ drone gradually becomes more and more prominent as the piece unfolds, resulting in a final stretch that feels weirdly meditative despite its sinister, churning undercurrent.Notably, the album's two pieces were designed to "reflect into each other," so the following "Affinity Birds" opens as a slowly undulating and calm mass of buzzing drones, then grows steadily more gnarled, ugly, and unsettling as close harmonies increasingly amass and linger malevolently.By the time it reaches the end, all of the grounding bass tones have vanished, leaving only an infernal and ghostly insectoid hum of clashing tones.The symmetry is perfect, as the album opens as a nightmare, fleetingly blossoms into something almost beautiful, then steadily dissolves into an even deeper nightmare.

If I had to choose a kindred spirit for The Hex of Light, the album that immediately springs to mind is Catherine Christer Hennix's landmark The Electric Harpsichord, as the two share a similarly nerve-jangling approach to harmony.I have no idea if Wesseltoft and Marhaug dabbled in Just Intonation themselves, but it does not matter, as they certainly manipulated microtonal shifts effectively enough to make their harmonies every bit as alien and disorienting as those of Christer Hennix. The similarities between the two album go deeper than their similarly drone-based structure and unconventional approach to harmony, however, as The Hex of Light evokes a similarly phantasmagoric, timeless, and ritualistic scene.Granted, modular synths are a bit more anachronistic for an ancient temple than a harpsichord, but the illusion manages to hold up regardless (presumably since the duo seem to use synths or synth-like sounds solely because of the degree of microtonal control they offer).I am always reluctant to embark upon indulgent poetic fancies when describing an album, but I think such a thing is warranted here, as more prosaic language feels hopelessly inadequate in conveying the scope of The Hex of Light's power and mystique.This album's diabolical, chittering thrum feels exactly like the sounds I would expect to be gnawing at my sanity if I were a feverish and malarial explorer desperately trying to escape a cursed jungle after stumbling upon a horrifying occult ritual.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

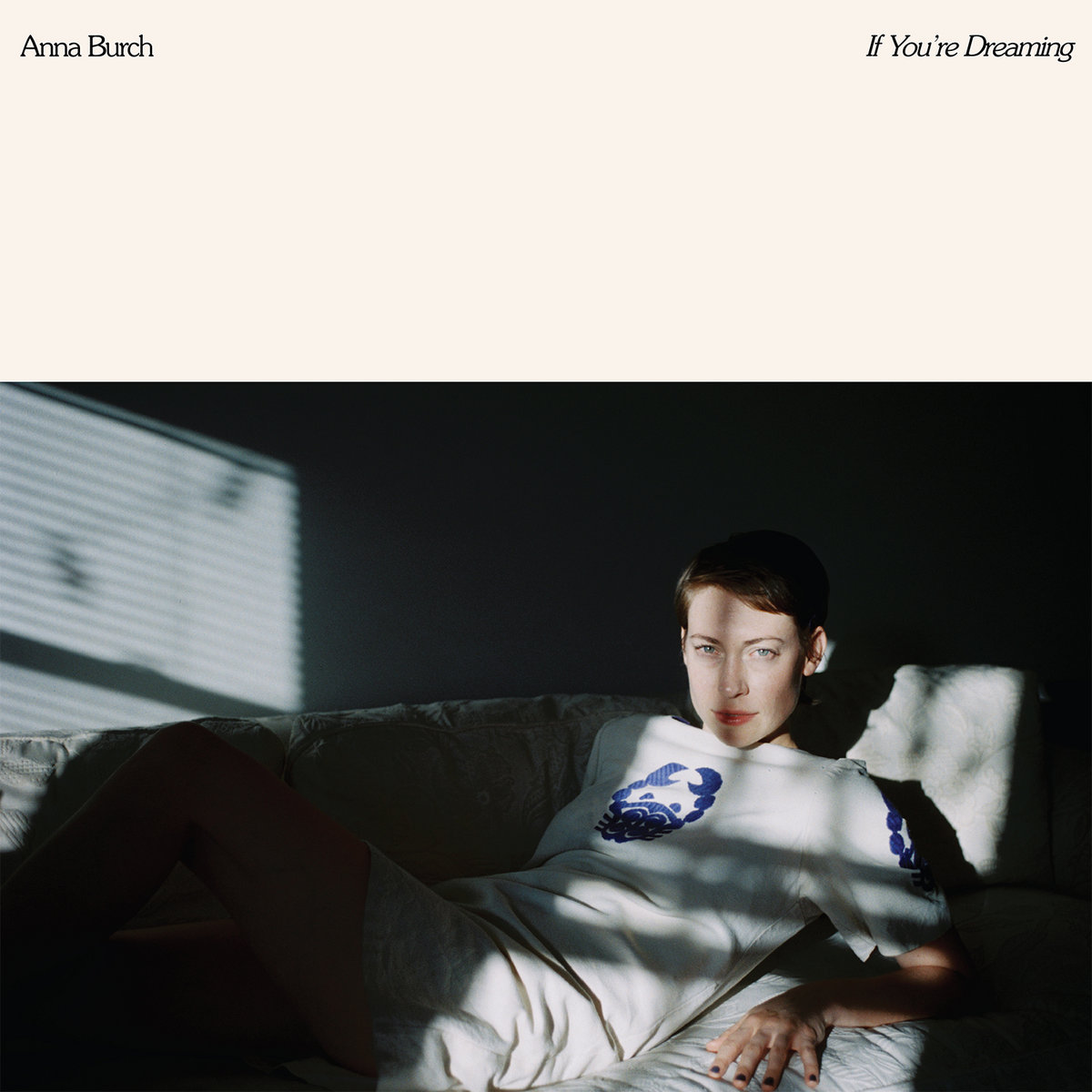

Anna Burch is the singular creative force behind so-called "bummer pop" album If You're Dreaming. This album is a departure from Burch's earlier effort, and one that shows off her stylistic breadth and thematic depth. In contrast to the high energy first album, for this release she slips into the fireside armchair and contemplates feelings and relationships, rocking gently and raising in inquiring brow. It's a relaxation of pace that I much prefer, and every song on the release is an instant favorite.

Anna Burch is the singular creative force behind so-called "bummer pop" album If You're Dreaming. This album is a departure from Burch's earlier effort, and one that shows off her stylistic breadth and thematic depth. In contrast to the high energy first album, for this release she slips into the fireside armchair and contemplates feelings and relationships, rocking gently and raising in inquiring brow. It's a relaxation of pace that I much prefer, and every song on the release is an instant favorite.

Polyvinyl

If You're Dreaming is within the musical lineage of one of my most beloved artists—Hope Sandoval. The song "Jacket" is eerily similar to that earlier pioneer, with its reverberating electric guitars enclosed in atmosphere and mystery, propelled by narcotic female vocals. It's music that I will always associate with a dock on a lake, an empty dingy chained to the end. It's a little forlorn, and a little lost in thought, with just enough restless energy to keep it moving.

Standard four piece rock instrumentation comprise the majority of these songs, with splashes of keys and effects. Burch's vocals are mellow and unadorned, except for the occasional harmonizing overdubs. The lyrics are like a conversation had with a friend, gently chiding with lines like: "Even if I could read you / Would you believe / Does it somehow feel good / Being misunderstood," and "There is someone to love / Is that what you're dreaming of?" The backing band cradles her personal musings nicely, meandering easily through pop rock and the odd jazz chord, all with the same tenderness that the singing evokes.

It's a beautiful album for getting cozy and contemplating. I'm excited to have been introduced to Anna Burch right at the moment when she seems to be creatively stretching. She's someone to watch.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Sarah Davachi is a luminary in the field of electroacoustic music, with a master's degree from Mills College and an in progress doctorate from UCLA. Her self-released album Horae builds on a noteworthy career that includes 17 releases and worldwide tours with such notable contemporaries as Grouper, William Basinski, and Oren Ambarchi. Named after Greek goddesses, this album evokes the same feelings and visceral reactions experienced when listening to similarly unstructured soundscapes found in nature. Describing the post of the horae at the gates to Olympus, this minimalist document is regal, stately, and emotionally potent.self-released

Sarah Davachi is a luminary in the field of electroacoustic music, with a master's degree from Mills College and an in progress doctorate from UCLA. Her self-released album Horae builds on a noteworthy career that includes 17 releases and worldwide tours with such notable contemporaries as Grouper, William Basinski, and Oren Ambarchi. Named after Greek goddesses, this album evokes the same feelings and visceral reactions experienced when listening to similarly unstructured soundscapes found in nature. Describing the post of the horae at the gates to Olympus, this minimalist document is regal, stately, and emotionally potent.self-released

It opens with "First Triad," a duet for flying saucers, the visual allusion carrying the pitches as they streak across the sky. Tones approach and diverge, bleating their incongruous frequencies, like play between complementary and contrasting colors. With standout track "Carpo," tones curl and embrace in a concordant melange, like a heart swelling union between two life partners. Dense with emotion, it brings a blush to the face.

"Second Triad" is more of a static drone, with warm harmonies and gradual embellishments. It feels like a long, sustained operatic note, deepening into a trilling vibrato. For me, "Third Triad" invokes the same emotions of comfort and security as a Mozart horn concerto—the sound color is similar, with samples swiftly beating and shifting in a womb like environment. The track with the most restless motion to it, "Dysis," launches right into bold sweeping tones, expanding and contracting with a touch of the blues.

In Davachi's other recordings and live performances, she works with a large variety of instruments, creating sonic environments of completely different timbres than that of Horae. Appreciators of her signature voice will find much to enjoy in the back catalogue.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

In what appears to be his first solo release in five years, North Dakota resident Matt Taggart’s PCRV covers a bit of everything defined as noise on Deprecating Technology. Across the 40 minute duration of this tape he runs the full gamut: shrill sound collage, sustained wall noise, and even some hushed parts that would qualify as electro-acoustic. It might be all over the place on paper, but consistent production, as well as his use of what resembles vintage computer tones, makes for what truly sounds like a unified album.

In what appears to be his first solo release in five years, North Dakota resident Matt Taggart’s PCRV covers a bit of everything defined as noise on Deprecating Technology. Across the 40 minute duration of this tape he runs the full gamut: shrill sound collage, sustained wall noise, and even some hushed parts that would qualify as electro-acoustic. It might be all over the place on paper, but consistent production, as well as his use of what resembles vintage computer tones, makes for what truly sounds like a unified album.

Right from the onset of "Process Nothing," Taggart throws out shrill electronic pulsations and stuttering passages that sound like rotting computer tapes, all enshrouded within massive rumbling reverbs.There is quite a bit that happens in the span of barely a minute.This hyperkinietic dynamic continues onto "Allow Revision," a mass of blown out electronic explosions and digital cut-ups, with the occasionally discernible loop giving some semblance of rhythm.It is hard to not feel some parallels to classic Pain Jerk work, but it never seems like an imitation.

The opening to "Rope Burns" features Taggart going in a distinctly different direction:an impenetrable wall of static and jet engine noise that eventually relents to the chaotic bleeps and tones from the previous two pieces.It is still overall harsh and rapid, but he allows a bit more breathing room into the mix and the passages of heavy, low-end bass tones nicely contrast with the erratic stop/start dynamics."Encompass Resolve" also has a more restrained, sparse mix, but the brittle noise is stretched out with another chaotic, rapid-paced structure.

The lengthier "Overpaid Transgressions" has a bit of everything going on.Immediately opening with a blast of good old 1990s American mid-range noise, Taggart reshapes things into an orchestra of deranged computers.The mix builds and collapses, transitioning to a mass of sickly tones and dying engines.The piece opens up towards the end, with a more overtly synth-heavy, structured sound, before going out back into full on noise.

Deprecating Technology certainly emphasizes the harshness and chaos throughout, but this is not necessarily the rule.The short "Fern" is a short piece of strange insect-like clicking that, due to its simplicity, is even more disconcerting than the more blown out bits.The concluding "Coagulation" has some aggressive flare-ups, but much of the piece is a sparse hum and crackle up front, and then waxy, squeaky noises to conclude.

Matt Taggart draws from a a wide array of what has come to define what noise is on this tape, but it does not come across as disjointed or unfocused at all.Working with his palette of electronic bleeps and beeps and largely dynamic structures, there is a sense of consistency from piece to piece.Taggart’s influences may be pretty obvious at times, but his work is fresh and unique, resulting in what is, to put it quite simply, an excellent noise tape from start to finish.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Concluding Die Stadt and Auf Abwegen's ambitious reissue program is Monoposto, a collaborative work between Asmus Tietchens and CV Liquidsky (Andreas Hoffmann) from 1991. Originally a vinyl only release, the album comes across as an approach to digital electronic instrumentation akin to his work in the analog domain from the 1980s. With prevalent guitar, and even a Neil Young cover, however, it makes for one of his more accessible and conventionally musical works.

Concluding Die Stadt and Auf Abwegen's ambitious reissue program is Monoposto, a collaborative work between Asmus Tietchens and CV Liquidsky (Andreas Hoffmann) from 1991. Originally a vinyl only release, the album comes across as an approach to digital electronic instrumentation akin to his work in the analog domain from the 1980s. With prevalent guitar, and even a Neil Young cover, however, it makes for one of his more accessible and conventionally musical works.

The album proper is presented in a different running order than the original vinyl release for some reason, and like previous reissues in this series, there is also some bonus material appended at the end.Like others in the reissue program, such as Geboren, Um Zu Dienen and Notturno, Tietchens and Hoffmann’s sound on this disc has distinct industrial tinges to it.But unlike those records, and the bizarre synth pop works from the Sky Records era, everything here has a very digital sheen to it.The processed guitar throughout "Junge Hoden" almost sounds like a MIDI approximation, and the metallic rhythm of "Drangsal am Hauptbahnhof" resembles a deconstructed KMFDM or Klinik from that area stripped down and reconfigured in a much more quirky, idiosyncratic manner.

The digital sound is not just from the instrumentation, but also production:there is a massive amount of digital reverb covering these songs, like the murk throughout "Vergessene Jungens" or the simulated spring reverb and depressive synths throughout the aforementioned "Drangsal am Hauptbahnhof."Also, digitally thin rhythms and wobbly synths of "Schlotzen" are enhanced via bass string plucks, but still has that undeniably brittle texture.Amidst the guitar tones of "Fraueninnenhygiene," the two also add in a crunchy, low bit rate rhythm track as well.

The addition of guitar makes this a rather unique work in Tietchens's expansive catalog.Throughout "Der Appelbeker Kreis," there are loopy rhythms, but also a guitar part that, with its odd effects and processing, could have been pulled from Dome's first record."DDR" is another standout with a rhythm that emerges from a dark background perfectly.The key element, however, is a guitar melody that is not at all far removed from the sound Lush was utilizing on their early EPs that were contemporaneous to Monoposto.The cover of Neil Young’s "My My, Hey Hey," titled as "Aus Heiterem Himmel" is unsurprisingly the most conventional sounding from a structural perspective, but is still melodic guitar cast atop a metallic knocking and other randomly injected noises, making it not necessarily an obvious reworking.

The bonus material consists of three pieces that fit right in with the original record."Prinzip Hoffmann" stands out a bit in comparison with its more complex rhythm programming, but the growing darkness is not that dissimilar."Schwachholz Vorsetzen" has a bit more of a stuttering feel to it from a structural standpoint, and "Liquidsky Spricht", which appeared on the Soleilmoon compilation Das Digitale Vertrauen is simply a bit of radio noise and Hoffmann thanking the listener for buying the album which, as the final installment of the reissue series, is a fitting coda.

Like his earlier works, Asmus Tietchens's work with CV Liquidsky fits in nicely with his early synth pop and vintage industrial excursions, using the instrumentation and production of late 1980s/early 1990s industrial music, but in a way no one else would.It may sound distinctly from its era, but the unique approach the duo take on Monoposto results in a timeless quality that is just as brilliant as it was 29 years ago.It is an excellent conclusion to a 17 year reissue campaign that is among the most impressive I have followed.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

JR Robinson and Esther Shaw explore the Greek philosophy of Stoicism and the path to happiness known as eudaimonia for this new album with the addition of Thor Harris (Swans) and Jamie Stewart (Xiu Xiu). This is a contrast to the prior album, The Alone Rush, which was steeped in personal tragedy. To achieve eudaimonia involves accepting the present moment as it exists, and not to be controlled by pleasure or fear of that moment. Wrekmeister Harmonies present a form of eudaimonia through We Love to Look at the Carnage with songs that expose the strength achieved through victory over darkness. Written in Oregon in near total isolation, the music feels like a winter evening in the Northern Hemisphere. Their translation of winter to sound is marked by understated grim simplicity, melodies syncopated with urgent resignation through orchestral gloom, and a mastery of emotional subtlety. It is an intensely intimate musical journey that begins at night but ends in the promise of a new day.

JR Robinson and Esther Shaw explore the Greek philosophy of Stoicism and the path to happiness known as eudaimonia for this new album with the addition of Thor Harris (Swans) and Jamie Stewart (Xiu Xiu). This is a contrast to the prior album, The Alone Rush, which was steeped in personal tragedy. To achieve eudaimonia involves accepting the present moment as it exists, and not to be controlled by pleasure or fear of that moment. Wrekmeister Harmonies present a form of eudaimonia through We Love to Look at the Carnage with songs that expose the strength achieved through victory over darkness. Written in Oregon in near total isolation, the music feels like a winter evening in the Northern Hemisphere. Their translation of winter to sound is marked by understated grim simplicity, melodies syncopated with urgent resignation through orchestral gloom, and a mastery of emotional subtlety. It is an intensely intimate musical journey that begins at night but ends in the promise of a new day.

The journey begins at "Midnight to Six," greeted by Shaw’s piano and angelic vocals, belying the downturn to come when Robinson’s deep baritone enters. Robinson insists "With a pain in my side, all the hours collide along a fault line" before being haunted by Harris’ urgent and pounding percussion, fading into a defiant wind that bridges to "Still Life with Prick Cancer." All seems well on the journey until Stewart’s choppy vocals, overlaid by warning bells and the clang of hammer on steel, indicate otherwise. All members combine forces after the 3-minute mark with a jumble of drone reminiscent of the band’s previous punch moments. Robinson informs us that "locked in silence at 4 a.m., a flower blooms inside my chest, with so much passion it makes the blood sing," echoed by a sonic commotion that bleeds the song into…

Savage Beauty; a perfect description for the power of "Coyotes of Central Park." The most melodic of the album, this is the most conventional Wrekmeister have ever been, with my only complaint that the song may be too short. Savage beauty is exactly what Robinson implores as he encourages us to "See how they dance in the pale blue moonlight, no one hears them, no one knows the savage beauty of having the moon by the throat."

Savage beauty leads the way to savage reality with "The Rat Catcher." Shaw’s and Robinson’s interweaving instrumentation would indicate the journey’s remainder will be easy, but peaceful journeys don’t include "spent half my time putting the lights out, blinding myself with whatever I could stick into my arm." Calm makes way for waves of tension, layered with Stewart’s creepy electronics, the crescendo of Robinson’s guitar, Shaw’s wailing violin, and colored by Harris’ cold percussive clangs before descending into chaos that fades away into the deceivingly gentle but lyrically harrowing "Immolation." With an onslaught of metal that Wrekmeister is known for, the journey ends with a beautiful mess of guitars, chants, drones, and stark electronics.

The intense peaks and valleys audible on prior albums have been refined, and this subtlety is precisely what makes We Love to Look at the Carnage their most powerful work to date. Vocals are smoothed in support of more melodic, gentle embellishments. Their lyrical craft is at their strongest and worth the closer listen. There is nothing upbeat or bouncy about this album. For perspective, writing this review on a gray, rainy day with the events of 2020 in the background was a genuine strain on my mental attitude, but We Love to Look at the Carnage was the perfect soundtrack to match. Wrekmeister Harmonies offers shelter from the storms we face each day within each song by claiming victory, to travel through that metaphorical bleak winter night and come out the other side and break through to the sun of a new day.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Three piece girl band Big Joanie hailing from the UK have made a splash internationally, opening for such luminaries as Sleater-Kinney and Bikini Kill and attracting much critical acclaim. Landing somewhere between thematically punk rock and musically pop rock, they manage to sound cool and direct while lamenting about men, sex, friendship, and modern life as black women.

Three piece girl band Big Joanie hailing from the UK have made a splash internationally, opening for such luminaries as Sleater-Kinney and Bikini Kill and attracting much critical acclaim. Landing somewhere between thematically punk rock and musically pop rock, they manage to sound cool and direct while lamenting about men, sex, friendship, and modern life as black women.

The Daydream Library Series

The vocal delivery and instrumental attack lacks the rage of riot grrl, but that’s not to say their music is without confrontation. They tackle subjects inherent in their identity as marginalized minorities when they please, such as on the sarcastic track "Token." But for the most part, topics are personal and light, dealing with feelings and relationships.

The music is concordant and propulsive, with electric guitar that’s simple and catchy and drums played with a deft touch—more of a hand clapper than a head banger. The album has energy, but it’s an understated energy. They’re the kind of songs that are nice to listen to at home, but that you know they could probably tear it up when playing live. Opening track "New Year" is especially upbeat and compelling, with an unforgettable vocal hook. Bookended track "Cut Your Hair" is also a standout, a bit of sweet lullaby sung to someone loved.

This album, Sistahs, is the first full length release for Big Joanie and shows more polish than their earlier singles. Their sound has coalesced into something both driving and digestible, with a feminist voice that I hope to hear more from in the future.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This latest release from Student of Decay’s eclectic and unpredictable sister label is an unexpectedly melodic and accessible one, though it still fits comfortably within Soda Gong's ethos of exploring the more playful and trend-averse fringes of experimental music. While this is technically only Malkin's second solo album under his own name, he has been a prolific and ubiquitous figure in the LA scene for quite some time, surfacing in a number of different guises and collaborations. In fact, I just belatedly discovered that he played on one of my favorite songs from the Not Not Fun milieu (LA Vampires/Maria Minerva's "A Lover & A Friend"). Given that pedigree, it is not surprising that A Typical Night in the Pit has a very "LA" feel to it, but it is an endearingly vaporous and neon-lit one, evoking a kind of dreamlike and hazy strain of jazz. It maybe errs a bit too much on the side of atmosphere to feel like a truly substantial statement, but Malkin has both style for days and an impressively unerring instinct for manipulating light, space, and texture. If I saw a film with this as the soundtrack, I would definitely stick around to the end to find out who the hell managed to make smoky, noirish jazz sound so fresh and endearingly skewed.

This latest release from Student of Decay’s eclectic and unpredictable sister label is an unexpectedly melodic and accessible one, though it still fits comfortably within Soda Gong's ethos of exploring the more playful and trend-averse fringes of experimental music. While this is technically only Malkin's second solo album under his own name, he has been a prolific and ubiquitous figure in the LA scene for quite some time, surfacing in a number of different guises and collaborations. In fact, I just belatedly discovered that he played on one of my favorite songs from the Not Not Fun milieu (LA Vampires/Maria Minerva's "A Lover & A Friend"). Given that pedigree, it is not surprising that A Typical Night in the Pit has a very "LA" feel to it, but it is an endearingly vaporous and neon-lit one, evoking a kind of dreamlike and hazy strain of jazz. It maybe errs a bit too much on the side of atmosphere to feel like a truly substantial statement, but Malkin has both style for days and an impressively unerring instinct for manipulating light, space, and texture. If I saw a film with this as the soundtrack, I would definitely stick around to the end to find out who the hell managed to make smoky, noirish jazz sound so fresh and endearingly skewed.

Like a lot of obsessive music fans, I went through a fairly deep "classic jazz" phase at one point and a lot of those albums definitely left a significant impression on me.However, some iconic albums did not resonate with me at all and many of the ones that most underwhelmed me could loosely be described as "cool jazz."I bring this up because Malkin and his collaborators explore roughly that same stylistic territory with A Typical Night in the Pit, but manage to do it in a way that highlights all of the best qualities (slow, sultry grooves and languorous, soulful soloing) while avoiding all of the worst ones (soporific pacing, indulgent solos in boring scales, general blandness).That welcome innovation is best illustrated by a piece like the brief "Some KJAZZ Eternity," as a smoldering saxophone solo unfurls over a slow, sexy groove rendered vaguely hallucinatory by lingering smears of electric piano chords.Rather than sounding like a bunch of white dudes in embarrassing hats trading solos, it instead evokes the shadowy, neon-lit interior of a strip club in a futurist noir, Blade Runner-esque version of Los Angeles.Also of note: both "Some KJAZZ Eternity" and the similarly wonderful "Secondhand Identity" clock in at around two minutes, as Malkin seems to have little patience for meandering or lingering on a theme longer than necessary.On one hand, it is a little exasperating that some of the best pieces on A Typical Night in the Pit are so damn brief, but I can also appreciate Malkin's "all killer, no filler" approach.While he may not always fully capitalize on his strongest ideas, Malkin is rarely guilty of allowing a theme to overstay its welcome at all.

Although A Typical Night is largely defined by its prominent jazz influence, jazz is far from the only influence that is evident on the album: Malkin is more of an eclectic and chameleonic experimentalist than anything resembling an aspiring traditional jazzman.In fact, the album's jazzier inspirations seem to come primarily by way of Malkin's love of '70s & '80s Robert Altman and Alan Rudolph films and their scores.For the most part, Malkin's experimental tendencies are limited to hazy production touches and a very fluid approach to genre boundaries with these nine songs, but some more overt weirdness does surface near the end of the album.For example, the impressionistic "Perfect Terminal" blends together rippling piano ambiance, shuffling and echoing percussion flourishes, a stuttering digitized voice, and an elegantly blurred saxophone solo, while the blurting and disjointed "Estacionamiento Privado" resembles the kind of mutant, deconstructed funk that might have come out of the late '70s Sheffield industrial scene.Elsewhere, Malkin takes a lighter and more playful approach with "Sixth Street Conversation," channeling his jazzier impulses in endearingly plinking, herky-jerky fashion.My favorite piece on the album, however, is probably "Through a Rain-Streaked Window," which enhances Malkin's "noir jazz" aesthetic with some nice vaporwave/Not Not Fun-style pop touches in the form of a structured progression of warm synth chords.It still feels a bit too artfully disjointed and deconstructed to fully resemble a "pop song," but it comes close enough to feel like a half-remembered fever dream homage to synth-driven '80s hookiness.

My sole real critique of this A Typical Night in the Pit is merely that only a few pieces stick around long enough to feel fully formed, which makes the album feel like a teasing glimpse of greatness rather than a completely satisfying effort.Pointing that out feels a little wrong and unfair though, as I am otherwise thoroughly impressed and delighted by this album as an artistic statement (and its elusive, dreamlike character is almost certainly by design).Malkin has conjured up quite a wonderful and unique stylistic niche for himself and his execution is damn near flawless, as I absolutely love how everything sounds (particularly the stand-up bass and the saxophones).I also enjoy all the subtly hallucinatory touches in the periphery, as voices and field recordings unpredictably and enigmatically drift in and out as the album unfolds.From a production and arrangement standpoint, A Typical Night is an absolute master class.Moreover, Malkin wisely keeps the entire album grounded in a solid melodic structure, so there are very few passages that feel unmemorable or weightlessly ethereal.Consequently, I sincerely hope Malkin decides to explore this direction further in the future, as A Typical Night in the Pit is an inventive, understated, and eminently listenable gem that feels like the potential precursor to an absolutely brilliant follow-up.For now, however, this release is quite possibly the strongest album to date from either Malkin or Soda Gong.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

For the most part, I can always be relied upon to enthusiastically support any talented artist who leaves their comfort zone behind to explore increasingly weird and uncharted territory. I do have my weaknesses, however, and one of the major ones is my undying love for classic Mille Plateaux/Chain Reaction-style dub techno. Consequently, I am hopelessly fixated on early Vladislav Delay albums like Entain and the newly reissued Multila. That is a damn shame, as Sasu Ripatti has made quite a lot of wonderful and forward-thinking music since and I have definitely not dug into his later work nearly as much as I should. This latest album, the first new Vladislav full-length in roughly five years, is a particularly effective and timely reminder that I am an absolute chump for sleeping on many of Ripatti's major statements over the years. Rakka is quite an ambitiously intense and inventive affair, seamlessly blurring together elements of Tim Hecker-style blown-out ambiance, power electronics, techno deconstruction, and production mastery into an explosive tour de force.

For the most part, I can always be relied upon to enthusiastically support any talented artist who leaves their comfort zone behind to explore increasingly weird and uncharted territory. I do have my weaknesses, however, and one of the major ones is my undying love for classic Mille Plateaux/Chain Reaction-style dub techno. Consequently, I am hopelessly fixated on early Vladislav Delay albums like Entain and the newly reissued Multila. That is a damn shame, as Sasu Ripatti has made quite a lot of wonderful and forward-thinking music since and I have definitely not dug into his later work nearly as much as I should. This latest album, the first new Vladislav full-length in roughly five years, is a particularly effective and timely reminder that I am an absolute chump for sleeping on many of Ripatti's major statements over the years. Rakka is quite an ambitiously intense and inventive affair, seamlessly blurring together elements of Tim Hecker-style blown-out ambiance, power electronics, techno deconstruction, and production mastery into an explosive tour de force.

Given the number of varying guises that Sasu Ripatti has recorded under over the years, it is hopeless to try to define his aesthetic with any degree of accuracy.Hell, even this one project has undergone a constant and significant series of evolutions since it first began.That said, I still feel fairly comfortable in stating that Rakka is quite unlike anything that Ripatti has recorded previously.Much like some of Richard Skelton's stronger works, Rakka's creative leap forward was triggered by an unusual and unmusical inspiration, as Ripatti's muse was essentially the arctic tundra.He spent some time in the wilderness there and was understandably struck by the elemental power and brutality of the environment.In an abstract sense, Rakka is his attempt to replicate that experience to some degree.Obviously, pure sound has its limitations, so Ripatti's live sets are enhanced by an intense visual component crafted by his wife (Antye Greie-Ripatti/AGF), yet the album nevertheless feels quite heavy and fully formed on its own.In fact, it feels a hell of a lot like a rave being ripped apart by a howling blizzard.

Unsurprisingly, very little survives from that imaginary rave in recognizable form, but the deconstructed fragments of beats and chords still seem to form the album's backbone, albeit in ephemeral, corroded, and stuttering form.The title piece is an especially strong example of that aesthetic, as a pulsing chord struggles to be heard beneath a cacophony of skittering, distorted drums and a churning host of other strangled and static-ravaged sounds.All of the individual components of techno are present, yet they exist in a radically reworked context that sounds nothing like techno.Instead, it feels like a roiling, intense, and impressively hostile miasma of colliding sounds.

While Ripatti’s stated intention was to strip away the "meaninglessness of hooks and melodies" and subvert conventional rhythms, he proves himself to be remarkably skilled and inventive in imbuing each of Rakka's seven pieces with its own distinctive character.Naturally, raw power does a lot of the heavy lifting that beats and hooks might have done, but there are still enough buried traces of songcraft to transcend anything resembling a noise album.Instead, Rakka is more like a series of meticulously crafted song fragments undergoing violent paroxysms.

I suppose roughly half of the album can be said to resemble variations of the title piece, though the variations are significant ones. For example, "Raataja" mingles its seething, pulsing drones with spasmodic eruptions of jackhammering kick drums, while "Raajat" resembles a steadily intensifying and enveloping roar disrupted by rhythmic loops of heavy machinery. Elsewhere, "Rakkine" ventures quite close to straight-up power electronics, as a half-pummeling/half-stammering rhythm is ravaged by bursts of extremely distorted vocals and harsh noise.Some of the other detours, like the more ambient "Raakile" and the near-blast beat crescendo of "Rampa" work a bit less well as individual pieces, but prove themselves to be very effective elements in enhancing the album's overall dynamic arc.Notably, the album’s finest piece, "Rasite," comes at the end of that arc, calling to mind a vintage Tim Hecker or Fennesz gem that has been enhanced with submerged dub-style sub bass, then completely decimated by strafing machine gun fire, an earthquake, and a volcano.

If there is a caveat with Rakka, it is only that it falls more squarely on the "art" side of the "art versus entertainment" spectrum than most (or all) of Ripatti’s previous releases: it is not so much a fresh batch of songs as it is a sustained and intense experience.That is just fine by me, however, as Rakka is every bit as tightly edited and exactingly produced as the more accessible Vladislav Delay fare.In fact, I am legitimately amazed at how masterfully Ripatti was able to balance brute force and exquisite craftsmanship with this release, even while most nuance and subtlety is unavoidably eclipsed by its gales of noise and punishing flurries of percussion.Ripatti has always been a forward-thinking artist that played a significant role in shaping the direction of electronic music, but this album twists and breaks the form to such a degree that it will be quite a tall order for anyone else to follow him down this path.In fact, it is kind of a radical inversion of Ren Schofield's relentless and punishing Container project: Schofield is a noise artist who has made violence danceable, while Ripatti is a techno artist who has driven dance music completely off its rails, yet still somehow remains in total control of where that flaming and screeching metaphorical trainwreck is headed.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Alison Chesley, a classically trained cellist, is one of those performers whose collaborations are many and varied, spanning across genres and decades in her long career. Her credits include contributions to over 100 albums1, with styles ranging from post-rock, to metal, to college rock, to new music, to film score. Solo project Helen Money is the culmination of these influences, with cello the principal actor in her experiments with chamber rock, subtle effects to round sharp corners, and heavy riffs to chop the serenity back up again.

Alison Chesley, a classically trained cellist, is one of those performers whose collaborations are many and varied, spanning across genres and decades in her long career. Her credits include contributions to over 100 albums1, with styles ranging from post-rock, to metal, to college rock, to new music, to film score. Solo project Helen Money is the culmination of these influences, with cello the principal actor in her experiments with chamber rock, subtle effects to round sharp corners, and heavy riffs to chop the serenity back up again.

The opening track of Atomic, Helen Money’s 6th release, is aptly called "Midnight," establishing the mood of the entire album squarely inside the witching hour, with all the moodiness of an underground Chicago haunt thick with smoke and regret. Cello is voiced clearly in the forefront in many-layered blossoming daubs. The more sedate of her ideas are reminiscent of her collaboration with The For Carnation, Louisville post-rockers closely associated with Slint. Touching on chamber music but returning time and again to a rock framework, she creates lovely and eerie instrumentals for strings, keys, drums and guitar. The more ferocious tracks are more reminiscent of the blistering hiss and chug of ISIS, with none of the vocals but all of the heaviness of a turpentine bath. Somehow, despite weaving in and out of these heavy and tender modes, she maintains a through line that unifies the album—a connecting presentation that is both sensual and gothic, leavened with bursts of jagged peaks.

Alison Chesley has been making music for longer than I have been alive, but her substantial output is new to me, and it is a quite welcome discovery. Some of the bands she’s performed with—Broken Social Scene, Rachel’s, The Sea & Cake—are my musical love affairs. This release, "Atomic," swept me off my feet during the first 10 seconds, and carried that standard of beauty throughout. It’s post-rock without falling into the trap of being too derivative, owning its own distinct personality and sound, and drawing you into its cradle and bow. It’s a record that haunts, at times naked and beseeching, at others flared and screeching. It lingers with the listener like an old hurt, the tangled cello lines echoing into the stillness of your night.

This album is coming at a time when the artist’s vision is a much needed balm for the anxieties of a world gone topsy turvy. In her own words, "I’ve been thinking a lot about how the earth is our home; the universe; and how fragile this world is and how connected we all are to everything."2 Even as we adjust to the new reality of physical social distancing, our nobelist instincts as human beings suffering a collective crisis do come forward—to spend time reconnecting virtually with family and friends, to support our fellow community members in need if we can, and to redouble our efforts to see that the music industry we love survives and thrives.

Read More