- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

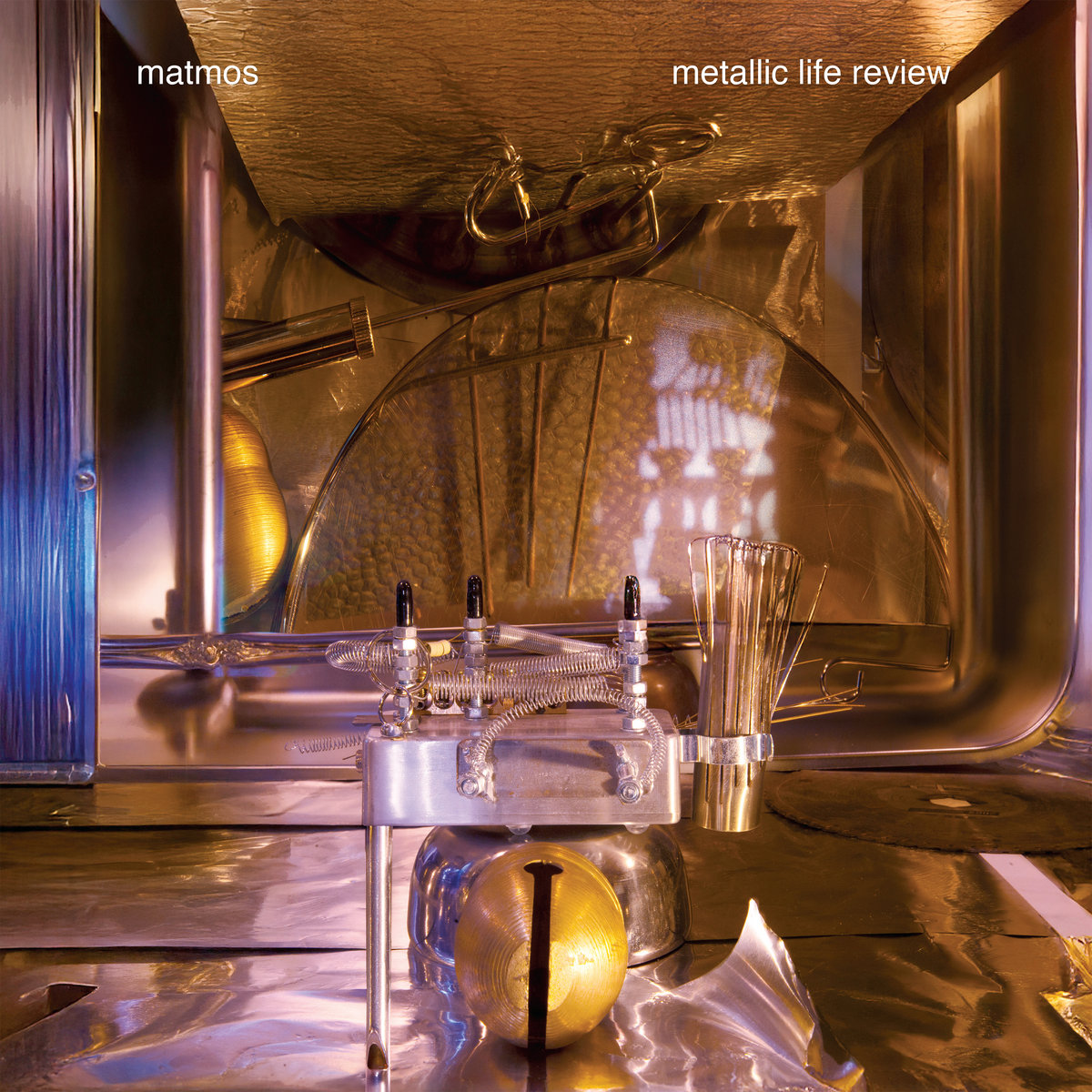

This latest release from the duo of M.C. Schmidt and Drew Daniel is billed as a “compressed fast-forward of Matmos’ career with a sonic parade of the metallic objects from their lives,” as they attempted to mimic the psychological phenomenon of “life review” that people experience during near-death experiences, but quixotically decided to do it exclusively through metallic sound sources. Naturally, that constraint resulted in quite an eclectic and interesting instrumental palette that ranges from “pots and pans from each member’s childhood” to metal reels used in the recording of iconic early musique concrète pieces at Paris's INA/GRM. Notably, however, this album is a bit less uncompromisingly purist than I expected, as the late Susan Alcorn contributed pedal steel to a couple of pieces (still technically metal though).

This latest release from the duo of M.C. Schmidt and Drew Daniel is billed as a “compressed fast-forward of Matmos’ career with a sonic parade of the metallic objects from their lives,” as they attempted to mimic the psychological phenomenon of “life review” that people experience during near-death experiences, but quixotically decided to do it exclusively through metallic sound sources. Naturally, that constraint resulted in quite an eclectic and interesting instrumental palette that ranges from “pots and pans from each member’s childhood” to metal reels used in the recording of iconic early musique concrète pieces at Paris's INA/GRM. Notably, however, this album is a bit less uncompromisingly purist than I expected, as the late Susan Alcorn contributed pedal steel to a couple of pieces (still technically metal though).

The album opens with one of its strongest pieces, as a gong-like crash kicks off a ritualistic percussion workout that sounds like the gamelan-inspired intro to a wild avant-metal album (albeit one that prominently features spaghetti bowls and cheese graters). Notably, it is also the first of two pieces featuring guest percussionist Thor Harris, so the metallic rhythm is an impressively intricate and virtuosic one, yet it is actually a creaky door that ultimately steals the show. Fittingly, the piece is entitled “Norway Doorway,” but I never would have guessed the source of the wild free-jazz sax wails otherwise. Harris returns once more for the following “Rust Belt,” which initially sounds like a free drummer going nuts in a well-stocked kitchen, but gradually blossoms into a sexy mutant disco groove enhanced with a host of spacy dub touches.

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

On her first vinyl LP release, multidisciplinary artist Susana López presents four compositions that blend synths, field recordings, and other sounds treated into pure abstraction. Layered and processed, they are reassembled into compositions that are quite beautiful yet have an alien quality to them that makes them all the more engaging.

On her first vinyl LP release, multidisciplinary artist Susana López presents four compositions that blend synths, field recordings, and other sounds treated into pure abstraction. Layered and processed, they are reassembled into compositions that are quite beautiful yet have an alien quality to them that makes them all the more engaging.

Expansive synth tones and what resembles grinding field recordings lead off on "Mundus Imaginalis." Although what seems identifiable would be characterized as either electronic or mechanical, the feeling is an organic one. As she layers in buzzing and subtle, gurgling like noises, the piece becomes a slow, glacial paced one that has incredible depth to it. Comparably, "Materia Vibrante" continues that open, drifting in space feeling, but the overall piece is more defined by tonality as opposed to texture. There is a sense of wide open spaces that are filled with lush and complex melodies.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This debut release from young Cambridge, Massachusetts-based composer Gabriel Brady was apparently recorded in his dorm room with little more than a bouzouki, a violin, and a “compact modular synth setup,” but it often sounds like it could have been the work of a veteran and visionary tape loop artist. As far as I know, there were no actual tape loops involved in these recordings, but Brady ingeniously achieved a similar effect by feeding his acoustic instruments into his synth, which acted as a "sound chamber for further manipulation (loops, effects, textures).”

This debut release from young Cambridge, Massachusetts-based composer Gabriel Brady was apparently recorded in his dorm room with little more than a bouzouki, a violin, and a “compact modular synth setup,” but it often sounds like it could have been the work of a veteran and visionary tape loop artist. As far as I know, there were no actual tape loops involved in these recordings, but Brady ingeniously achieved a similar effect by feeding his acoustic instruments into his synth, which acted as a "sound chamber for further manipulation (loops, effects, textures).”

I have heard it said before that some artists release their greatest work while unsuccessfully trying to mimic their influences, then lose that precarious magic when they finally get it right. Hopefully, that fate never befalls Brady, but it is worth noting that his primary inspirations are French New Wave film scores and early Impressionist composers like Satie and Debussy. More specifically, Brady set out to chase the “sense of yearning” conjured by Jean Constantin’s 400 Blows score. In that regard, Brady succeeds most beautifully on the back-to-back highlights “Ordinary” and “Land and Sea.”

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

I believe this album’s unusual title is a palindromic way to convey that it is intended as a spiritual sequel to 2019’s Tutti, as it certainly seems to continue the stylistic trajectory of its predecessor. Notably, however, Tutti was assembled from repurposed archival material to coincide with an exhibition whereas 2t2 is composed of entirely new material. Aside from that, the two albums are quite similar, as this one is also a blend of driving synthesizer vamps and moody ambient pieces. To my ears, this latest outing is not quite as strong as Tutti, as it is a bit lean on hooks, but Cosey certainly tries out a lot of interesting ideas (including some new techniques that emerged from her deep research into Delia Derbyshire’s archive). Some of those experiments are definitely more satisfying than others, but there is one killer new piece (“Never The Same”) that can easily hang with Cosey’s previous career highlights.

I believe this album’s unusual title is a palindromic way to convey that it is intended as a spiritual sequel to 2019’s Tutti, as it certainly seems to continue the stylistic trajectory of its predecessor. Notably, however, Tutti was assembled from repurposed archival material to coincide with an exhibition whereas 2t2 is composed of entirely new material. Aside from that, the two albums are quite similar, as this one is also a blend of driving synthesizer vamps and moody ambient pieces. To my ears, this latest outing is not quite as strong as Tutti, as it is a bit lean on hooks, but Cosey certainly tries out a lot of interesting ideas (including some new techniques that emerged from her deep research into Delia Derbyshire’s archive). Some of those experiments are definitely more satisfying than others, but there is one killer new piece (“Never The Same”) that can easily hang with Cosey’s previous career highlights.

Conspiracy International

Unsurprisingly, “Never The Same” generally falls within Cosey’s synthpop comfort zone, though it deceptively fades in with a bit of nightmarish ambiance before the slow throb of the groove fully comes into focus. While the sensuous groove is definitely one of the better ones on the album, the piece's primary allure lies in the fact that Cosey simply played to her strengths: the unprocessed vocals feel unguarded and vulnerable, there is a repeating vocal hook, there is cool howling psychedelia in the periphery, and her cornet playing adds smoky, noirish splashes of melody.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

The latest opus from this Gdansk-based composer is the final part of dark trilogy of albums that began with 2013’s Liebestod and continued with 2017’s Rite of the End. According to Wesołowski, the three albums are united by themes of “existential matters such as love, death, decay” as well as “an apocalyptic and Promethean ultimate end.” Given that ambitious scope, it is no surprise that Wagner was a major inspiration for the previous installments, but this one is partially rooted in W.G. Sebald’s writings on “the nature of memory” and “how thoughts and desires overlap and mutate over time.” That “Sebaldian nature” is most prominently manifested in Wesołowski’s decision to sample his own sketches and unused recordings, but the elemental intensity of these pieces suggests that the shadow of Wagner still looms large in his vision.

The latest opus from this Gdansk-based composer is the final part of dark trilogy of albums that began with 2013’s Liebestod and continued with 2017’s Rite of the End. According to Wesołowski, the three albums are united by themes of “existential matters such as love, death, decay” as well as “an apocalyptic and Promethean ultimate end.” Given that ambitious scope, it is no surprise that Wagner was a major inspiration for the previous installments, but this one is partially rooted in W.G. Sebald’s writings on “the nature of memory” and “how thoughts and desires overlap and mutate over time.” That “Sebaldian nature” is most prominently manifested in Wesołowski’s decision to sample his own sketches and unused recordings, but the elemental intensity of these pieces suggests that the shadow of Wagner still looms large in his vision.

Unheard of Hope

In keeping with those outsized dramatic themes, Song of the Night Mists features field recordings from Tatra Mountains and organ recordings from Saint Nicholas' Basilica (played by the composer’s brother Piotr). Notably, the field recordings were used in a film by sound designer Michał Fojcik and Wesołowski notes that “you can hear cracking ice, streams, footsteps in the snow and the wind, and a real avalanche, recorded from the inside.”

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest album from Guido Zen’s Abul Mogard alter ego marks both the debut of his Soft Echoes label and an interesting detour from his usual working methods, as he reworked unreleased material from past projects and texturally enhanced it with sounds culled from his late uncle’s collection of classical 78s.

This latest album from Guido Zen’s Abul Mogard alter ego marks both the debut of his Soft Echoes label and an interesting detour from his usual working methods, as he reworked unreleased material from past projects and texturally enhanced it with sounds culled from his late uncle’s collection of classical 78s.

As far as I can tell, little of the actual music from those dusty shellac platters made it onto the album, but Mogard certainly worked wonders from that rich palette of hiss and crackle. The opening “Following a dream” is an especially strong example of that alchemy, as the dreamy melancholia of the central synth motif is quite lovely on its own, but it is the cyclically crashing, slow-motion waves of static that provide both the hypnotically languorous rhythm and sense of raw elemental intensity.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest speaker-straining salvo from the duo of James Ginzburg and Paul Purgas was fittingly debuted at the Tate Modern to accompany “a large-scale survey of the global history of art and technology” entitled Electronic Dreams. I say “fittingly” because Dissever both feels like a uniquely visceral and violent strain of high art and some kind of massive and menacing industrial installation. I suppose both of those things can be said about some previous emptyset albums as well, but this one is unquestionably more aggressively minimalist and driven by machine-like repetition. Notably, the conceptual inspiration behind that move was an interest in the intertwined evolutions of “cosmic rock, minimalism and electronic music” and late-20th century advances in production technology, so the duo went appropriately analog/retro with both their gear and recording techniques.

This latest speaker-straining salvo from the duo of James Ginzburg and Paul Purgas was fittingly debuted at the Tate Modern to accompany “a large-scale survey of the global history of art and technology” entitled Electronic Dreams. I say “fittingly” because Dissever both feels like a uniquely visceral and violent strain of high art and some kind of massive and menacing industrial installation. I suppose both of those things can be said about some previous emptyset albums as well, but this one is unquestionably more aggressively minimalist and driven by machine-like repetition. Notably, the conceptual inspiration behind that move was an interest in the intertwined evolutions of “cosmic rock, minimalism and electronic music” and late-20th century advances in production technology, so the duo went appropriately analog/retro with both their gear and recording techniques.

Thrill Jockey

The results are impressively visceral and brutalist, as each piece is essentially an inventive transformation of a single pulsing note into a heaving and hulking industrial juggernaut using a primitive array of dynamic effects. In fact, much of Dissever amusingly suggests either 1) the No Wave minimalism of Glenn Branca’s early ‘80s guitar orchestra work if he’d swapped out his guitars for heavy industrial machinery and a deep passion for sound system culture, or 2) one of Ellen Fullman’s Long String Instrument performances if she had come from a doom/sludge metal background (or at least a building demolition one). My personal highlight is the title piece, as it sounds like a blown-out and overloaded sound system suddenly became sentient and decided to vengefully wipe out the entire dancefloor with an onslaught of seismic bass waves and slashing metallic textures, but nearly every single song is a throbbing and sharp-edged masterpiece of harshly grinding textures, cool tricks with overtones and oscillations, and relentless, heaving physically. This is definitely a strong contender for my absolute favorite emptyset album to date, as Purgas and Ginzburg have conjured quite an immersive display of earth-shaking elemental power from just a handful of notes (and some expertly wielded early hardware).

Listen here.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest opus from the Opalio brothers is a pair of single-sided art LPs devoted to two very different performances featuring the duo’s longtime collaborator Joëlle Vinciarelli (Talweg/La Morte Young). In classic Opalio fashion, The Secret of the Space Bubble was inspired by a vision that Roberto had of four astronauts performing in zero gravity. The lucky fourth astronaut in this case is Talweg’s other half (Eric Lombaert) and the combination of his virtuosic freeform drumming with Vinciarelli’s strangled flugelhorn partially steers things in a more Sun Ra-esque spaced-out free jazz direction than usual. There are, however, some other unique factors in play, as the Opalios exclusively used Vinciarelli’s collection of unusual and ancient instruments rather than their usual gear. Also, it was recorded using only two ambient mics to create a “vortex of sound” where all of the sounds and their reverberations were “centrifuged/blended together” to achieve the necessary “space bubble” effect.

This latest opus from the Opalio brothers is a pair of single-sided art LPs devoted to two very different performances featuring the duo’s longtime collaborator Joëlle Vinciarelli (Talweg/La Morte Young). In classic Opalio fashion, The Secret of the Space Bubble was inspired by a vision that Roberto had of four astronauts performing in zero gravity. The lucky fourth astronaut in this case is Talweg’s other half (Eric Lombaert) and the combination of his virtuosic freeform drumming with Vinciarelli’s strangled flugelhorn partially steers things in a more Sun Ra-esque spaced-out free jazz direction than usual. There are, however, some other unique factors in play, as the Opalios exclusively used Vinciarelli’s collection of unusual and ancient instruments rather than their usual gear. Also, it was recorded using only two ambient mics to create a “vortex of sound” where all of the sounds and their reverberations were “centrifuged/blended together” to achieve the necessary “space bubble” effect.

Opax/Elliptical Noise/Up Against The Wall, Motherfuckers!

Even by MCIAA standards, it is quite a challenging and far out affair, as the aforementioned space jazz uneasily coexists with folk horror flutes, shimmering chimes, an inventively repurposed clock, and wordless vocals that resemble a bizarre experimental opera. At its best, it sounds like an antique clock shop has become possessed by the spirit of an alien gamelan ensemble, which is a quite mesmerizing environment to find oneself in. I especially loved the jangling and echoing metal sounds on this one. In fact, they almost make me wish that the individual sounds could be handed off to a team like Holy Tongue & Shackleton to be anchored to a heavy dub bassline, but that kind of accessibility is simply not on the alien agenda.

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

With these two releases (one of which is subscribers only and is still available as part of a full package), David Jackman concludes this monumental eight-part collection of what he deems as a single, unified work. Unsurprisingly, the sound of these two albums is drawn from elements and themes of the volumes that preceded, first in a dramatic culmination, then in a more restrained and mediative, befitting the concluding segments of such an expansive endeavor.

With these two releases (one of which is subscribers only and is still available as part of a full package), David Jackman concludes this monumental eight-part collection of what he deems as a single, unified work. Unsurprisingly, the sound of these two albums is drawn from elements and themes of the volumes that preceded, first in a dramatic culmination, then in a more restrained and mediative, befitting the concluding segments of such an expansive endeavor.

Steadfast, credited to D. Jackman (even with the series completed, I still am no closer to understanding the choice of artist name used for each of these discs), is two discs, while Scilence (as just Jackman) is the subscriber only final volume. Disc one of Steadfast still features this work in its most intensive form. Immediately an organ-like roar and what sounds like layered, digital delay feedback is an immediate hit to the senses. A down-tuned gong or bell appears early on, and the result resembles all of the elements he has been working with in the series tightly compacted into a single piece. Prominent low frequency tones and shifting delays added to the piece alternatingly resemble a swirling vortex of noise and the roar of a jet engine.

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

Two of Upstate New York’s prolific artists, Mike Griffin (Parashi) and Eric Hardiman (Rambutan) have both been responsible for a slew of tapes, vinyl, and CD/CDRs of work that can never be easily predicted. Either on their own or in collaborations, their work runs the gamut from harsh noise to complex abstract spaces and sometimes dabbling into more conventional musical realms. This split double disc set features each on their own, with the albums sounding rather different from each other, but with a clear artistic consistency and intent between the two.

Two of Upstate New York’s prolific artists, Mike Griffin (Parashi) and Eric Hardiman (Rambutan) have both been responsible for a slew of tapes, vinyl, and CD/CDRs of work that can never be easily predicted. Either on their own or in collaborations, their work runs the gamut from harsh noise to complex abstract spaces and sometimes dabbling into more conventional musical realms. This split double disc set features each on their own, with the albums sounding rather different from each other, but with a clear artistic consistency and intent between the two.

Griffin’s album, Wave Function Collapse, features him flirting with conventional musical features and structures, while still drifting into more cosmic abstractions. "Red Plague" is a mass of ghostly electronic whispers, propelled by an overdriven bass. His upfront, although lightly processed vocals give it the vibe of a deconstructed song. It becomes more pronounced as he shifts the bass sound to a more conventional one slips in a largely untreated guitar. "Swim in Petrol" is similarly musical in nature, pairing lo-fi style acoustic guitar and vocals relatively low in the mix, awash in reverb.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

Scott Morgan has been quietly and steadily releasing beautifully crafted and fog-veiled grayscale ambient-dub excursions for over a quarter century now so I was not expecting a huge creative leap forward this deep into the game, but Lake Fire may very well be the strongest loscil album of his career. Morgan’s breakthrough doesn’t sound like it came easily though, as this album was assembled from the reworked ruins of an aborted suite for electronics and ensemble (though one brooding and blackened piece from that suite (“Ash Clouds”) did manage to survive the culling). Notably, literal ash clouds were quite a significant inspiration this time around, as Lake Fire is something of an impressionistic road trip diary from a drive through the mountains of British Columbia while sky-blackening wildfires raged in the distance. In fact, the album cover is an actual photo of those smoke-obscured mountains that Morgan himself took from a rowboat on a lake.

Scott Morgan has been quietly and steadily releasing beautifully crafted and fog-veiled grayscale ambient-dub excursions for over a quarter century now so I was not expecting a huge creative leap forward this deep into the game, but Lake Fire may very well be the strongest loscil album of his career. Morgan’s breakthrough doesn’t sound like it came easily though, as this album was assembled from the reworked ruins of an aborted suite for electronics and ensemble (though one brooding and blackened piece from that suite (“Ash Clouds”) did manage to survive the culling). Notably, literal ash clouds were quite a significant inspiration this time around, as Lake Fire is something of an impressionistic road trip diary from a drive through the mountains of British Columbia while sky-blackening wildfires raged in the distance. In fact, the album cover is an actual photo of those smoke-obscured mountains that Morgan himself took from a rowboat on a lake.

Obviously, veiled & water-adjacent melancholy is nothing new for Morgan, but he brings a fresh intensity and an ingenious new approach to rhythm to his usual vision on pieces like the brilliant opener “Arrhythmia.” The insistent pulse of skipping loops suggests a malfunctioning amusement park wave machine that is furiously churning out waves of killer dub-techno fragments while its overworked pressure valves rhythmically vent bursts of steam. In fact, one of my favorite facets of this album is how masterfully Morgan creates rhythms with an unconventional palette of hisses, throbs, and subtle metallic textures rather than anything resembling a kick drum or cymbals.