- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Those who slip on the Mekons new album as a novice to the band andtheir wiles will no doubt be a bit dumbfounded. Listening to therecord, I could hear countless passages of music that I've heardelsewhere, or something so similar I would swear it was influenced bysomeone else — if I didn't know that these songs were written almost 30years ago and just recently recorded for the release. Punk Rockis a study of a band at their absolute finest, re-embracing musicthey'd written off a quarter-century ago in favor of loftier heightsand bolder experimentations. Maybe all that experience has fed thesesongs, too, as there's a wisened approach to the compositions. Pairedwith the naked aggression and powerhouse vocals is a variedinstrumentation and brave altering of tempo. These songs have a punkheart but their brains are scrambled in how to present it the heart'sfeelings. It's like punk viewed through different lenses, or a tributealbum of great punk songs by various bands, some punk some not. Thatthe band chose to record these songs to celebrate their 25thanniversary as a band is extremely telling, as they truly went backtheir beginnings to dredge this up. The album is an experience that'ssometimes rollicking fun, sometimes tear in your beer, but always aninteresting ride. The stomp of "Teeth" that opens the record is a greatindication of what lies inside, for the most part, with all instrumentsblazing to the finish line. This sentiment is echoed on "I'm So Happy"and "32 Weeks," as well, but the moments are staggered in betweentracks that slow it down a bit, bringing across a purified version ofthe song at its most naked, without the pomp and circumstance thatsometimes comes with the genre. What I hear most of all on the recordis how these songs influenced the band in the beginning and how thatspirit affected every release since.

Those who slip on the Mekons new album as a novice to the band andtheir wiles will no doubt be a bit dumbfounded. Listening to therecord, I could hear countless passages of music that I've heardelsewhere, or something so similar I would swear it was influenced bysomeone else — if I didn't know that these songs were written almost 30years ago and just recently recorded for the release. Punk Rockis a study of a band at their absolute finest, re-embracing musicthey'd written off a quarter-century ago in favor of loftier heightsand bolder experimentations. Maybe all that experience has fed thesesongs, too, as there's a wisened approach to the compositions. Pairedwith the naked aggression and powerhouse vocals is a variedinstrumentation and brave altering of tempo. These songs have a punkheart but their brains are scrambled in how to present it the heart'sfeelings. It's like punk viewed through different lenses, or a tributealbum of great punk songs by various bands, some punk some not. Thatthe band chose to record these songs to celebrate their 25thanniversary as a band is extremely telling, as they truly went backtheir beginnings to dredge this up. The album is an experience that'ssometimes rollicking fun, sometimes tear in your beer, but always aninteresting ride. The stomp of "Teeth" that opens the record is a greatindication of what lies inside, for the most part, with all instrumentsblazing to the finish line. This sentiment is echoed on "I'm So Happy"and "32 Weeks," as well, but the moments are staggered in betweentracks that slow it down a bit, bringing across a purified version ofthe song at its most naked, without the pomp and circumstance thatsometimes comes with the genre. What I hear most of all on the recordis how these songs influenced the band in the beginning and how thatspirit affected every release since.Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The Frames' lack of notoriety in the US is not due to any lack ofeffort on their parts. With two releases on Overcoat, including their2001 studio album For the Birdsand a compilation of unreleased tracks, the band has been on theseshores for several club tours, getting their name out and entertainingthe masses with their polished live sound. Where other Irish bands havetried this route with limited success on a grand scale, The Frames seemto want a home-grown fanbase, teaming their small club presence withintimate albums recorded with Steve Albini and in someone's kitchen. In2003, they recorded a live album in front of a sold-out Dublin crowd,and released it to great acclaim in their home country, where it toppedthe charts and critic's polls at year's end. Now, with a new deal onEpitaph's Anti imprint, Glan Hansard and the boys are making another goon American audiences on a slightly larger scale, with that very livealbum as the first release to give people a taste of the already richcatalog of songs the band has accrued. Three of their studio albums arerepresented with more than one track, and several of them becomeextended rock jams in front of an audience. Many have said that TheFrames are a live band first, and hearing the CD I can understand why.Hansard gives his all vocally, yelping at the top of his lungs inareas, and the band blisters their way through songs, though the crowddoesn't seem to mind. In fact, it's always a good sign if you have thecrowd singing along with every word, and on several tracks that'sexactly what happens, most notably on "Lay Me Down," where the crowdbecomes an almost impromptu choir. Hansard also proves an amusing andamiable frontman, conversing with the crowd and offering stories andanecdotes here and there. Though the album is a tour-de-forceculmination of all their energies, there are small missteps, like theinclusion of "Ring of Fire" into "Lay Me Down," and the fact that themajority of the songs will be lost on a new listener, with no studioversions to compare them to as the albums are not available in the USand are rather difficult to order. That said, it's a great primer fortheir new studio album due later this year, and a great show of theextremes the band goes through, from somewhat down-tempo numbers to theall-out assault of "God Bless Mom." One thing's for sure: with anupcoming US tour supporting it-boy Damien Rice, I'll be one of thefirst in line to see if they can live up to Set List.

The Frames' lack of notoriety in the US is not due to any lack ofeffort on their parts. With two releases on Overcoat, including their2001 studio album For the Birdsand a compilation of unreleased tracks, the band has been on theseshores for several club tours, getting their name out and entertainingthe masses with their polished live sound. Where other Irish bands havetried this route with limited success on a grand scale, The Frames seemto want a home-grown fanbase, teaming their small club presence withintimate albums recorded with Steve Albini and in someone's kitchen. In2003, they recorded a live album in front of a sold-out Dublin crowd,and released it to great acclaim in their home country, where it toppedthe charts and critic's polls at year's end. Now, with a new deal onEpitaph's Anti imprint, Glan Hansard and the boys are making another goon American audiences on a slightly larger scale, with that very livealbum as the first release to give people a taste of the already richcatalog of songs the band has accrued. Three of their studio albums arerepresented with more than one track, and several of them becomeextended rock jams in front of an audience. Many have said that TheFrames are a live band first, and hearing the CD I can understand why.Hansard gives his all vocally, yelping at the top of his lungs inareas, and the band blisters their way through songs, though the crowddoesn't seem to mind. In fact, it's always a good sign if you have thecrowd singing along with every word, and on several tracks that'sexactly what happens, most notably on "Lay Me Down," where the crowdbecomes an almost impromptu choir. Hansard also proves an amusing andamiable frontman, conversing with the crowd and offering stories andanecdotes here and there. Though the album is a tour-de-forceculmination of all their energies, there are small missteps, like theinclusion of "Ring of Fire" into "Lay Me Down," and the fact that themajority of the songs will be lost on a new listener, with no studioversions to compare them to as the albums are not available in the USand are rather difficult to order. That said, it's a great primer fortheir new studio album due later this year, and a great show of theextremes the band goes through, from somewhat down-tempo numbers to theall-out assault of "God Bless Mom." One thing's for sure: with anupcoming US tour supporting it-boy Damien Rice, I'll be one of thefirst in line to see if they can live up to Set List.Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Hot on the heels of Soul Jazz's The World of Arthur Russell, Audika Records releases Calling Out of Context, the first in a projected three volumes chronicling Russell's work throughout the 1980s. Where The World of compiled the best of his avant-disco sides originally released limited pressings in NYC's disco heyday, Context offers a glimpse at Russell's unreleased work, culled from his vast private archive of recorded material.

Hot on the heels of Soul Jazz's The World of Arthur Russell, Audika Records releases Calling Out of Context, the first in a projected three volumes chronicling Russell's work throughout the 1980s. Where The World of compiled the best of his avant-disco sides originally released limited pressings in NYC's disco heyday, Context offers a glimpse at Russell's unreleased work, culled from his vast private archive of recorded material.

The work contained herein goes even further down the idiosyncratic path in evidence on The World of's more abstract tracks such as "Schoolbell/Treehouse" and "Keeping Up." These songs make it clear that Russell was a perfectionist of sorts, meticulously adding echo, splices and overdubs to his songs until they achieved a complexity that, on the surface, can appear almost effortless. These tracks cannot be deemed "disco" in any sense. They sound more like bedroom pop masterpieces, made with a working knowledge of the patterns and clichés of current pop music, but with a striking originality that transcends its time and technology. "The Platform on the Ocean" showcases Russell's striking use of distortion and stereo panning, and his throaty, soulful vocals curl and echo around the clipped African percussion. His simplistic, almost childlike lyrics are elevated to high poetry with inflected repetition and Russell's distinctive production: "On the wood platform on the ocean/I looked down and saw the fish/Which way its tail was pointing and why." Even tracks that sound very much like a sincere attempt at hackneyed 80's pop balladry, such as "You and Me Both," retain a dreamy, alien distance that is utterly magical. It's as if we are seeing 80's pop filtered through Arthur Russell's dreams and hallucinations, and this altered perception allows the music to arrive untainted by its tenuous attachment to the tired clichés of the period. Many of these songs come from a shelved album called Corn, a strangely appropriate symbol for the sonic alchemy that unites the urban sprawl of NYC with the windswept, oceanic expanses of the Midwest, Russell's birthplace and spiritual homeland. Some track are marred by crude drum programming, but Russell's intuitive approach to the cello and keyboards more than make up for these weaknesses. For me, encountering Arthur Russell's experimental disco work three years ago was a revelation, like rummaging through an attic and stumbling upon a collection of perfectly eccentric artwork that was there all the time, waiting to be discovered. It often occurred to me that Russell's released material must be only the tip of a vast, multifaceted iceberg, and Calling Out of Context wonderfully proves my suspicions were correct. -

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Adam Pierce has evolved Mice Parade from its humble beginnings to a full-fledged accomplished live ensemble, a feat especially impressive given his other dealings in HiM, touring with M√∫m, and running Bubble Core. After the success and bombast of that experience, Pierce went back home and recorded another album mostly by himself, but he felt the need to incorporate his experiences on the road and some of his friends from other projects, culminating in the fantastic new work of Obrigado Saudade.

Adam Pierce has evolved Mice Parade from its humble beginnings to a full-fledged accomplished live ensemble, a feat especially impressive given his other dealings in HiM, touring with M√∫m, and running Bubble Core. After the success and bombast of that experience, Pierce went back home and recorded another album mostly by himself, but he felt the need to incorporate his experiences on the road and some of his friends from other projects, culminating in the fantastic new work of Obrigado Saudade.

Mice Parade of old is represented, with the Cheng making an appearance and the DIY ethics, but there's a new breath and heartbeat in these songs, where Pierce tries his hands in new realms through familiar tactics. Guitar is presented in a number of beautiful ways on the record, with minimalist drumming and percussion allowing for an unintruded splendor to awaken and flourish on several tracks. Elsewhere, Pierce has captured the fervor and proficiency of the live band with the freefall of improvisation — or so it seems at least. With his fierce drumming and love of keys, the songs take on a fluid and dynamic bend, evolving as they continue, eventually resting at a comfortable stasis that never bores. Vocals from Múm vocalist Kristin Anna Valtysdottir on two tracks add a quaint and understated beauty; innocent-sounding and utterly familiar in this setting, even though it is their first recorded pairing. Doug Scharin of HiM also adds a bit of drums on "Out of the Freedom World," sure to be a reference to the "Into the Freedom World" tracks on Mokoondi, and Chris Conti's guitar work is also not to be discounted or missed. Pierce has crafted a truly wonderful album in Obrigado, due in no small part to his travels and experiences.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This release should arrive with a grain of sadness for, in January, Reynols disbanded after ten years of tireless activity. The prolific Argentine group spent the majority of this time in relative obscurity, forging ahead with large ambitions and an unflinching devotion to idiosyncratic craft that inevitably left them well-situated within the pantheon of frayed roots-rockers, brash experimenters, and psychedelic casualties. Their willingness to experiment with the most eccentric of concepts always made Reynols seem extra special, even among the small crop of similarly broad-minded collectives.Sedimental

This release should arrive with a grain of sadness for, in January, Reynols disbanded after ten years of tireless activity. The prolific Argentine group spent the majority of this time in relative obscurity, forging ahead with large ambitions and an unflinching devotion to idiosyncratic craft that inevitably left them well-situated within the pantheon of frayed roots-rockers, brash experimenters, and psychedelic casualties. Their willingness to experiment with the most eccentric of concepts always made Reynols seem extra special, even among the small crop of similarly broad-minded collectives.Sedimental

The group's catalog forms a sidewinding trip through torrid homemade noise rock, vintage free-form freaking, drone opuses, and a number of fantastical pieces composed for increasingly wayward instrumentation, of which Whistling Kettle is certainly one. Without the visceral edge of Blank Tapes, their surprisingly abrasive work of processed and layered tape hiss, or the baffling atmospherics of the 10,000 Chickens Symphony, sourced in what must be a gigantic, cavernous coop, Whistling Kettle brings more of a lyrical approach to Reynols' consistently adventurous arrangements. Performed on "baritone, tenor, contralto, and soprano whistling kettles," the quartet moves with a reserved, almost classical rigor that may come as a surprise to those indoctrinated by the coarse psych jams of earlier releases. Kettles drift closer to wails and howls rather than whistles, but the music supplies enough controlled tension to prevent the slip into gratuitous or brainless display. In fact, the four chrome mouthpieces do little to reveal their simple construction, each part contributing to a quivering, animate strand of sound that can only be described as otherworldly. The opener, "Andante Mogal," with its strained insistence, immediately reminded me of Jack Nance in Eraserhead, sitting patiently before the steaming vaporizer that attends his sick, inhuman child. There, like here, the kettle's whistle is something recognizable, though uncomfortable and veiled in mystery and expectation. Comparisons to Ligeti's obelisk-speak score for 2001 come easily during "Moderato uno Surido Fermo" where pitches maintain a frightening vocal range, undulating with reverent moans. The quartet escalates into its final and most impressive section, "Allegro Repuliom Lanidelo," as kettles produce grating screams and calls, sounding like the ambience from some dark, interstellar rainforest. Even at this noisy plateau, however, Whistling Kettle maintains a fragile, hushed quality which must be due to the unique timbre of the kettle. This "thinness" becomes both a callback to the medium and production of the piece, as well as one of the more interesting aspects of the music taken alone. It adds a beautiful layer of melancholy to the piece, while making the whole seem just as likely to dissolve, inconsequentially, like steam into the room.

Read More

- Michael Patrick Brady

- Albums and Singles

The Chicago Underground (whose members vary in number on their various releases) uses the malleable forms of jazz and electronic music to explore sounds and thoughts that could only be captured in the vistas of these boundless styles. Slon is an experiment in forms and styles, exploring the brassy expressionism of both genres to deliver a stirring display of meaning and intent through their inspired tones.

The opening squalls of "Protest" are immediate, like a fist raised in the air, standing out with a direct intensity that breaks out of the din of high hats and ride cymbals that pepper the air. As the track progresses, the melody and rhythm begin to double back on themselves through overdubs, slightly out of phase but still in concert with one another, building and moving along the same path. The tension created by these overlays increases the urgency as the trio begins to sound like a throng of voices all searching for the same step. "Zagreb" begins with a low rustling of machinery in the distance, or warm air rushing through a subway tunnel, before a slinky bass line and moody cornet overtake the scene, like steam rising off a rain slicked city street. Mazurek's horn playing is intensely sultry, an alluring hook into the dusky rhythm work of bassist Noel Kupersmith and drummer Chad Taylor. The album's title track blends an ethereal, disembodied horn with a clattering of aggressive blips of electronica, transporting the initial impulses that would typically emerge from the end of a horn or drum stick deep through a processor. The percussive, pixilated energy highlights that while the medium may grant artists a wider selection of ways to express themselves, it is still up to the artist to find those words. "Slon," along with the sparse ambience of "Kite" demonstrate that the Chicago Underground is quite adept at pulling the pieces together, whatever language they are speaking. The abstractions only intensify on "Palermo," which assembles the slow attack and fast falloff of reversed cymbal hits with a drippy beat and slippery progression. The track was seemingly assembled in the style of musique concrete, by tape cutter Bill Skibbe, furthering the ensemble's post-bop aesthetic and dedication to utilizing creative methods of presenting their sound. Though the acoustic and electric portions of Slon only intersect briefly, the way in which the Chicago Underground Trio employs them makes for a distinctly impressive piece.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I was late discovering 2002's Thought for Food,The Books' gorgeous debut album of electro-acoustic sound collages.That album had a guileless charm, the songs seeming to form out ofnowhere, spilling accidentally out of a patchwork of crisply reproducedguitars, seemingly random voice samples, field recordings and otherunidentifiable sources. The laptop-treated melodies fell roughly intothe same category as Four Tet's Pause album, but with an earfor synchronicity and miniature sound events that reinforced theprimacy of randomness, rather than the rigidity of regular rhythms andmelody. It was a refreshing album that unpredictably alternated betweennostalgia, absurdity and ingenuity. The Lemon of Pink wasreleased last year, and I was once again late in giving it a listen.With this record, The Books display the same talent for collage andmelody, but I can't help but notice how calculated, and hence lessenjoyable this album seems compared to the relatively unaffected Thought for Food.The ideas also seem a little thinner on this outing, and the wonderfulspaciousness of the debut LP has been replaced by a cavalcade of derigeur clicks and glitches, overwhelming many of the songs. Nocomplaints with the first few minutes of the album's opening track,cycling as it does through a scrapbook of scratchy, recollective folkand bluegrass records, a woman phonetically intoning the nonsensetitle, and a hundred indeterminate snatches of sound. But after thispromising couple minutes, it all segues into a relatively tepid CatPower-esque guitar-folk ballad that is something of a letdown followingits kaleidescopic introduction. "Tokyo" utilizes samples from aJapanese airport along with its vaguely Eastern guitar plucking andviolin sawing, digitally spliced and looped to circumvent melodyentirely. It's a bit of an obvious tactic for The Books. "There is NoThere" suffers from editing overload, but still manages to be quitelovely, especially the pause at the song's center for a sampledescribing Gandhi's theory of non-violent protest. This transforms intoa rollicking banjo and guitar duet that is reminiscent of John Faheyaugmented by Jim O'Rourke's talent for laptop assemblage. The rest of The Lemon of Pinkis largely short song sketches and useless filler, making this alreadybrief album even lighter in content, more like an EP than afull-length. I suppose if I had heard this album outside the context ofThe Books previous work, I might have thought that it was a passablypretty work of indie-folktronica. But coming as it did from a band thatproduced such an impressive debut, The Lemon of Pink is a bit deficient.

I was late discovering 2002's Thought for Food,The Books' gorgeous debut album of electro-acoustic sound collages.That album had a guileless charm, the songs seeming to form out ofnowhere, spilling accidentally out of a patchwork of crisply reproducedguitars, seemingly random voice samples, field recordings and otherunidentifiable sources. The laptop-treated melodies fell roughly intothe same category as Four Tet's Pause album, but with an earfor synchronicity and miniature sound events that reinforced theprimacy of randomness, rather than the rigidity of regular rhythms andmelody. It was a refreshing album that unpredictably alternated betweennostalgia, absurdity and ingenuity. The Lemon of Pink wasreleased last year, and I was once again late in giving it a listen.With this record, The Books display the same talent for collage andmelody, but I can't help but notice how calculated, and hence lessenjoyable this album seems compared to the relatively unaffected Thought for Food.The ideas also seem a little thinner on this outing, and the wonderfulspaciousness of the debut LP has been replaced by a cavalcade of derigeur clicks and glitches, overwhelming many of the songs. Nocomplaints with the first few minutes of the album's opening track,cycling as it does through a scrapbook of scratchy, recollective folkand bluegrass records, a woman phonetically intoning the nonsensetitle, and a hundred indeterminate snatches of sound. But after thispromising couple minutes, it all segues into a relatively tepid CatPower-esque guitar-folk ballad that is something of a letdown followingits kaleidescopic introduction. "Tokyo" utilizes samples from aJapanese airport along with its vaguely Eastern guitar plucking andviolin sawing, digitally spliced and looped to circumvent melodyentirely. It's a bit of an obvious tactic for The Books. "There is NoThere" suffers from editing overload, but still manages to be quitelovely, especially the pause at the song's center for a sampledescribing Gandhi's theory of non-violent protest. This transforms intoa rollicking banjo and guitar duet that is reminiscent of John Faheyaugmented by Jim O'Rourke's talent for laptop assemblage. The rest of The Lemon of Pinkis largely short song sketches and useless filler, making this alreadybrief album even lighter in content, more like an EP than afull-length. I suppose if I had heard this album outside the context ofThe Books previous work, I might have thought that it was a passablypretty work of indie-folktronica. But coming as it did from a band thatproduced such an impressive debut, The Lemon of Pink is a bit deficient.Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I sometimes catch myself slipping into label worship, a dangerous andinfrequent indulgence, but one that has yet to free my covetous eyefrom anything bearing the Rune Grammofon stamp. The Norwegian labelcelebrated its 30th release last year with this double-CD/book, actingnot so much as a retrospective, but more as an attempted rounding-outof the label's focus, a condensed look at what the past has produced,and what the future holds. Reading through Money Will Ruin Everything,I am immediately reminded of the many labels where such a release wouldbe long overdue. Founder Rune Kristoffersen cites Tzadik, 4AD, Factory,ECM, and Blue Note as inspirations, and there can be no denying thatGrammofon's consistency of presentation, commitment to quality, and itseffected grouping of a variety of artists, under one vaguely-definedethos, find much in common with those older, iconoclastic imprints. Therisk in releasing something like Money, especially so early ina label's life, is an over-confidence, a presumptuousness surroundingone's accomplishments thus far, and the possibility of thesepresumptions, proven or not, having a negative effect on futureprojects. Money is quick to address these concerns in itstitle, a cheeky flirtation with the idea of book as a sell-out, andlater inside, as the title page is preceded by the inscription: "Thisbook is a record cover." The effort to make the book seem like merelyan expanded sleeve is clear throughout; a great number of pages aredevoted to Kim Hiorthøy's beautiful design work, the hallmark forGrammofon discs and the undoubted cause of many introductions to thelabel. The pages include detailed examinations of each Hiorthøy sleevedesign, making clear the individuality of every release within thelarger schema, and making Money seem much more like an artbookthan an attempt to venerate the label's five-year past. The book evencontains an essay devoted to the designer's contributions, and thoughthe text brings comparisons to legends like Barney Bubbles and PeterSaville, these names do not feel far off after exposure to Hiorthøy'sbody of work, which perfectly suits the colorful character of theGrammofon catalog. The great variety and quality of the label's musicare the real focal points of the book and refuse to be compromised by Wireeditor Rob Young's introductory essay or the printed interview withKristoffersen. The owner's diplomatic words actually conclude Moneynicely, describing the release as "just a signpost in the road," aclaim that is perfectly supported by the music on the two discs, allexclusive and including substantial contributions from almost everyRune artist and a number of excellent tracks from otheryet-to-be-released members of the blossoming Norwegian scene (mostnotably music from Maja Ratkje's new Fe-mail project, new signingSusanna And The Magical Orchestra, and a brilliant track by Hiorthøyhimself). A crystalline, Nordic cool can be found in just abouteverything on Kristoffersen's label, but all easy comparisons endthere. The curating founder's tastes lie in the most shadowy andgrittiest of improv (Supersilent, Scorch Trio), in the most lulling andapproachable of experimental electronic (Skyphone, Alog), andeverywhere in between, grazing pristine folk (Tove Nilsen), shuddering,skeletal techno (Svalastog), and the unclassifiable music of MajaRatkje and Spunk, who seem to blur the lines between noise andchildhood. Perhaps the unifying characteristic of all Rune Grammofonmusic is that everything, given time, feels capable of deeply personalinvestment. There is a very unique immediacy to these artists' musicthat looks inward toward the same "enchanted domain" that essayistAdrian Shaughnessy describes in Hiorthøy's art, making it impossible todescribe Rune music without touching on all the spectral degrees,frequency shifts, and, as Rob Young says, the "subtle colour shading"that indicate a life lived, complex, radiant, and full of surprises. Moneyoffers little more than this; it is a celebration of what every Runerelease celebrates, and the perfect introduction to a label that hasyet to stop short of its own high standards.

I sometimes catch myself slipping into label worship, a dangerous andinfrequent indulgence, but one that has yet to free my covetous eyefrom anything bearing the Rune Grammofon stamp. The Norwegian labelcelebrated its 30th release last year with this double-CD/book, actingnot so much as a retrospective, but more as an attempted rounding-outof the label's focus, a condensed look at what the past has produced,and what the future holds. Reading through Money Will Ruin Everything,I am immediately reminded of the many labels where such a release wouldbe long overdue. Founder Rune Kristoffersen cites Tzadik, 4AD, Factory,ECM, and Blue Note as inspirations, and there can be no denying thatGrammofon's consistency of presentation, commitment to quality, and itseffected grouping of a variety of artists, under one vaguely-definedethos, find much in common with those older, iconoclastic imprints. Therisk in releasing something like Money, especially so early ina label's life, is an over-confidence, a presumptuousness surroundingone's accomplishments thus far, and the possibility of thesepresumptions, proven or not, having a negative effect on futureprojects. Money is quick to address these concerns in itstitle, a cheeky flirtation with the idea of book as a sell-out, andlater inside, as the title page is preceded by the inscription: "Thisbook is a record cover." The effort to make the book seem like merelyan expanded sleeve is clear throughout; a great number of pages aredevoted to Kim Hiorthøy's beautiful design work, the hallmark forGrammofon discs and the undoubted cause of many introductions to thelabel. The pages include detailed examinations of each Hiorthøy sleevedesign, making clear the individuality of every release within thelarger schema, and making Money seem much more like an artbookthan an attempt to venerate the label's five-year past. The book evencontains an essay devoted to the designer's contributions, and thoughthe text brings comparisons to legends like Barney Bubbles and PeterSaville, these names do not feel far off after exposure to Hiorthøy'sbody of work, which perfectly suits the colorful character of theGrammofon catalog. The great variety and quality of the label's musicare the real focal points of the book and refuse to be compromised by Wireeditor Rob Young's introductory essay or the printed interview withKristoffersen. The owner's diplomatic words actually conclude Moneynicely, describing the release as "just a signpost in the road," aclaim that is perfectly supported by the music on the two discs, allexclusive and including substantial contributions from almost everyRune artist and a number of excellent tracks from otheryet-to-be-released members of the blossoming Norwegian scene (mostnotably music from Maja Ratkje's new Fe-mail project, new signingSusanna And The Magical Orchestra, and a brilliant track by Hiorthøyhimself). A crystalline, Nordic cool can be found in just abouteverything on Kristoffersen's label, but all easy comparisons endthere. The curating founder's tastes lie in the most shadowy andgrittiest of improv (Supersilent, Scorch Trio), in the most lulling andapproachable of experimental electronic (Skyphone, Alog), andeverywhere in between, grazing pristine folk (Tove Nilsen), shuddering,skeletal techno (Svalastog), and the unclassifiable music of MajaRatkje and Spunk, who seem to blur the lines between noise andchildhood. Perhaps the unifying characteristic of all Rune Grammofonmusic is that everything, given time, feels capable of deeply personalinvestment. There is a very unique immediacy to these artists' musicthat looks inward toward the same "enchanted domain" that essayistAdrian Shaughnessy describes in Hiorthøy's art, making it impossible todescribe Rune music without touching on all the spectral degrees,frequency shifts, and, as Rob Young says, the "subtle colour shading"that indicate a life lived, complex, radiant, and full of surprises. Moneyoffers little more than this; it is a celebration of what every Runerelease celebrates, and the perfect introduction to a label that hasyet to stop short of its own high standards.- Kim HiorthøyWait

- Fe-mailJacob's Leketøy

- Andreas MelandEplesky

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

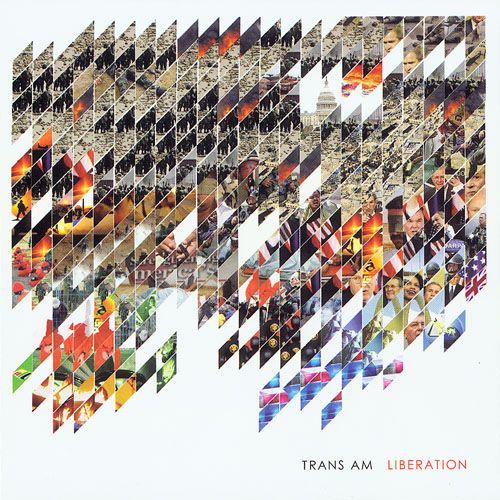

In 1948, George Orwell painted a bleak image of a future world. While 1984may have looked somewhat extreme, in the 1980s, the world did seemrather bleak with the cold war, the seemingly richest and greediestleaders the world had seen, and threat of total annihilation. The morepopular of the somewhat underground music played on these fears, asfuturistic synth music from people like Fad Gadget and Gary Numan werehardly utopian. It's been exactly 20 years since 1984 and the future isnow and it could easily be the future people have worried about foryears. The power of money and greed has corrupted the systems worldwidebeyond reasonable solutions; violence permeates everything; terrorismis ubiquitous; countries are merging; and the press is controlled andcensored by the government. The separation of wealth and middle classgrows exponentially where the urban wastelands are not so unimaginableas the onset of middle class poverty accelerates. Even the presidentspeaks a dumbed down version of the English language! Most relevant tothe review of this album: people in the country which claims to be themost free can now choose to detain people under without due process.Liberation is quite a weird concept. As the superpowers decide to"liberate" other countries, it seems their own back yard is hardlyliberated. Nowhere is this more apparent than Trans Am's residence,Washington DC, where armed military guards protect the gateways to thecapitol. A collage of fire, violence, and the home-grown billionaireswho are fucking this world up beyond belief cover this album, where,inside, the music is probably one of the most angry, intense albumsTrans Am have recorded. Fans who hated TA will be pleased toknow that the immediate urgency and intensity of older Trans Am hasreturned with a vengeance. The sung on the album are few, thankfully,and are clearly there as elements to the songs as opposed to thedriving hair band aesthetic that was TA. The album opens withthe lound, thunderous "Outmoder," and continues on with a cut up fromGeorge W. Bush on "Uninvited Guest" where the "president" speaks thetruth thanks to rearranged words. It's almost an homage toConsolidated's Friendly Fa$cism album from 1991 where Bush Sr'swords were cut up on the album's second track to portray similartruths. Trans Am compete with the madness as cars, traffic, sirens, andother city ambience can be heard outside as the band recorded much ofthis album with the windows open. It does take a few side steps to keepit varied, including the gorgeous "Pretty Close to the Edge" whichopens with an acoustic guitar riff and flows gently into a smooth drummachine ending before seamlessly jumping into the next track, "Is TransAm Really Your Friend?" The album is arranged for the vinyl medium,almost exactly 45 minutes (remember 90 minute cassettes?), with twoversions of the song "Divine Invasion" closing each side, where theband (probably unintentionally) essentially jams on the closing riff ofthe Beatles' "I Am the Walrus," which in my opinion is perhaps one ofthe most apocalyptic riffs of its time. Like any effective piece ofartwork, it's not the ability of the talents of the artist which makesthe piece of art great, it's the way in which the artwork makes theobserver think for themselves and make up their own mind. Trans Amaren't going to break out in any show-offery to prove they can playtheir instruments, they'd rather present something that will hopefullybe enough of something to react to.

In 1948, George Orwell painted a bleak image of a future world. While 1984may have looked somewhat extreme, in the 1980s, the world did seemrather bleak with the cold war, the seemingly richest and greediestleaders the world had seen, and threat of total annihilation. The morepopular of the somewhat underground music played on these fears, asfuturistic synth music from people like Fad Gadget and Gary Numan werehardly utopian. It's been exactly 20 years since 1984 and the future isnow and it could easily be the future people have worried about foryears. The power of money and greed has corrupted the systems worldwidebeyond reasonable solutions; violence permeates everything; terrorismis ubiquitous; countries are merging; and the press is controlled andcensored by the government. The separation of wealth and middle classgrows exponentially where the urban wastelands are not so unimaginableas the onset of middle class poverty accelerates. Even the presidentspeaks a dumbed down version of the English language! Most relevant tothe review of this album: people in the country which claims to be themost free can now choose to detain people under without due process.Liberation is quite a weird concept. As the superpowers decide to"liberate" other countries, it seems their own back yard is hardlyliberated. Nowhere is this more apparent than Trans Am's residence,Washington DC, where armed military guards protect the gateways to thecapitol. A collage of fire, violence, and the home-grown billionaireswho are fucking this world up beyond belief cover this album, where,inside, the music is probably one of the most angry, intense albumsTrans Am have recorded. Fans who hated TA will be pleased toknow that the immediate urgency and intensity of older Trans Am hasreturned with a vengeance. The sung on the album are few, thankfully,and are clearly there as elements to the songs as opposed to thedriving hair band aesthetic that was TA. The album opens withthe lound, thunderous "Outmoder," and continues on with a cut up fromGeorge W. Bush on "Uninvited Guest" where the "president" speaks thetruth thanks to rearranged words. It's almost an homage toConsolidated's Friendly Fa$cism album from 1991 where Bush Sr'swords were cut up on the album's second track to portray similartruths. Trans Am compete with the madness as cars, traffic, sirens, andother city ambience can be heard outside as the band recorded much ofthis album with the windows open. It does take a few side steps to keepit varied, including the gorgeous "Pretty Close to the Edge" whichopens with an acoustic guitar riff and flows gently into a smooth drummachine ending before seamlessly jumping into the next track, "Is TransAm Really Your Friend?" The album is arranged for the vinyl medium,almost exactly 45 minutes (remember 90 minute cassettes?), with twoversions of the song "Divine Invasion" closing each side, where theband (probably unintentionally) essentially jams on the closing riff ofthe Beatles' "I Am the Walrus," which in my opinion is perhaps one ofthe most apocalyptic riffs of its time. Like any effective piece ofartwork, it's not the ability of the talents of the artist which makesthe piece of art great, it's the way in which the artwork makes theobserver think for themselves and make up their own mind. Trans Amaren't going to break out in any show-offery to prove they can playtheir instruments, they'd rather present something that will hopefullybe enough of something to react to.Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

The past few months have seen the dispersal of a clutch of sideprojects by the four members of Volcano The Bear, including Songs ofNorway (Aaron Moore and Nick Mott), Earth Trumpet (Laurence Coleman),Guignol (Moore, Coleman and Jeremy Barnes of Bablicon) and El Monte(Mott solo). However, none of these projects have been as immediatelyenjoyable and as consistently rewarding as Daniel Padden's work as TheOne Ensemble. The Owl Of Fivesis Padden's second full-length album, a collection of composed piecesrun the gamut stylistically, but maintain an integrity that makes allof it unmistakably the work of the same talented musician. Paddenfreely borrows Oriental melodies, Fahey-style revenant blues, Indianclassical, plaintive piano ballads and outsider folk traditions tocreate a platter of tuneful exploration that captured and held myattention for its entire length. The One Ensemble's arrangements arecleverly sparse, using as little as possible to convey the fragilemelodies that populate the album. This compositional economy is the keyelement that allows The Owl Of Fives to achieve its stylisticshifts without seeming calculated or overwrought. In fact, as the albumprogresses from start to finish, the compounding of disparate musicstrategies gets better with each track, rather than becoming tiresome.The loose exotica of "Farewell, My Porcupine" welds Kyoto folk toArthur Lyman piano jazz, replete with multitracked non-verbal chanting.Elsewhere, stately medieval melodies are created in the coversationsbetween Padden's violin, acoustic guitar and piano. "Early Music of theMorning" takes its cue from the "morning raga," a term used in Indianclassical music to connote a languid, relaxing melody appropriate formorning ablutions. Against a hazy drone, Padden pulls gently bendingtones from his cello that brilliantly mimic a sitar. The recurringmusical theme of "Still Flinging Clowns" most closely resemble theBear, with its shambling, whimsical atmosphere and vocal glossolalia.The intimate production captures those tiny flaws - the scrape of cellostrings, the clearing of throats - that lend an organic, present-tensequality to the music. With The Owl Of Fives, The One Ensemble of Daniel Padden has created a work of understated, melodic brilliance.

The past few months have seen the dispersal of a clutch of sideprojects by the four members of Volcano The Bear, including Songs ofNorway (Aaron Moore and Nick Mott), Earth Trumpet (Laurence Coleman),Guignol (Moore, Coleman and Jeremy Barnes of Bablicon) and El Monte(Mott solo). However, none of these projects have been as immediatelyenjoyable and as consistently rewarding as Daniel Padden's work as TheOne Ensemble. The Owl Of Fivesis Padden's second full-length album, a collection of composed piecesrun the gamut stylistically, but maintain an integrity that makes allof it unmistakably the work of the same talented musician. Paddenfreely borrows Oriental melodies, Fahey-style revenant blues, Indianclassical, plaintive piano ballads and outsider folk traditions tocreate a platter of tuneful exploration that captured and held myattention for its entire length. The One Ensemble's arrangements arecleverly sparse, using as little as possible to convey the fragilemelodies that populate the album. This compositional economy is the keyelement that allows The Owl Of Fives to achieve its stylisticshifts without seeming calculated or overwrought. In fact, as the albumprogresses from start to finish, the compounding of disparate musicstrategies gets better with each track, rather than becoming tiresome.The loose exotica of "Farewell, My Porcupine" welds Kyoto folk toArthur Lyman piano jazz, replete with multitracked non-verbal chanting.Elsewhere, stately medieval melodies are created in the coversationsbetween Padden's violin, acoustic guitar and piano. "Early Music of theMorning" takes its cue from the "morning raga," a term used in Indianclassical music to connote a languid, relaxing melody appropriate formorning ablutions. Against a hazy drone, Padden pulls gently bendingtones from his cello that brilliantly mimic a sitar. The recurringmusical theme of "Still Flinging Clowns" most closely resemble theBear, with its shambling, whimsical atmosphere and vocal glossolalia.The intimate production captures those tiny flaws - the scrape of cellostrings, the clearing of throats - that lend an organic, present-tensequality to the music. With The Owl Of Fives, The One Ensemble of Daniel Padden has created a work of understated, melodic brilliance.samples:

Read More

- Michael Patrick Brady

- Albums and Singles

With their first full length release, They Threw us All in a Trench and Stuck a Monument on Top,Liars made their existence known to the world outside Williamsburg asthe most interesting product of that gentrified province, moreintriguing than the achingly deliberate sleaze of the Yeah Yeah Yeahsand decidedly darker than the goofy warble of the Rapture. A few yearsdown the road sees those latter two bands consorting with Carson Dalyand the buzz bin, while the recently shaken Liars lineup (minus theformidable bass and drum duo from the first LP) holed up in a NewJersey basement with their recording equipment and a notebook ofaudience-alienating ideas. The bands' prevailing neuroses have shiftedfrom bombast and bravado to paranoia and claustrophobia, which revealthemselves in oblique chants about witches and magic. "Broken Witch"(perhaps the shortest Liars song title to date) opens the album with adeep electronic pulse that sidles ominously alongside the staggeringdrum kit. Though intentionally hook-less, the song's offbeat, hypnoticfluctuations are as engaging as anything the band has done previously.The track sets the intended mood perfectly, conveying that this albumis not going to be pretty, and that it may not be danceable, but canstill be compelling enough to want to know where the rapidlyaccelerating incantations are leading. "There's Always Room on theBroom" mixes distorted voices and fuzzed out samplers with a creepyfalsetto sing-a-long chorus that eats away at the defenses like amalevolent earworm until the song has completely seized control ofrational judgment and begins to appear on the mind at its own volition.Combined with the hysterical strobe-animation video included with thedisc, the song is a devious and extremely successful attempt atreprogramming listeners and viewers to find the unlistenablelistenable. "They Don't Want Your Corn, They Want Your Kids" is theclosest to the early Liars bass lines and kick beats, a brief reprievefrom the murky fear of tracks like "We Fenced Other Gardens With theBones of Our Own," with its desperate cry of "We're doomed! We'redoomed!" that pierces through the indiscriminate chanting aboutcauldrons and evil spells. These songs capitalize on the darkness andspooky atmosphere that were hinted at in earlier efforts that wereobscured by the snap of a dance-punk bass line, driving the band (andtheir audience) into more and more unfamiliar territory until much oftheir sound and style are unrecognizable. They Were Wrong, So We Drownedis a reactionary record, forged in the glare of the spotlight thrustupon the band in the wake of their catchy debut. Rather than linger inthe comfortable bed they made for themselves, and potentially reap thebenefits of a wider appeal, they chose to start from scratch andchallenge themselves. In the end, the adventurousness of this decisionwill benefit them far more, as Liars have demonstrated that they are acapable, inventive band with more than just one trick up their sleeves.

With their first full length release, They Threw us All in a Trench and Stuck a Monument on Top,Liars made their existence known to the world outside Williamsburg asthe most interesting product of that gentrified province, moreintriguing than the achingly deliberate sleaze of the Yeah Yeah Yeahsand decidedly darker than the goofy warble of the Rapture. A few yearsdown the road sees those latter two bands consorting with Carson Dalyand the buzz bin, while the recently shaken Liars lineup (minus theformidable bass and drum duo from the first LP) holed up in a NewJersey basement with their recording equipment and a notebook ofaudience-alienating ideas. The bands' prevailing neuroses have shiftedfrom bombast and bravado to paranoia and claustrophobia, which revealthemselves in oblique chants about witches and magic. "Broken Witch"(perhaps the shortest Liars song title to date) opens the album with adeep electronic pulse that sidles ominously alongside the staggeringdrum kit. Though intentionally hook-less, the song's offbeat, hypnoticfluctuations are as engaging as anything the band has done previously.The track sets the intended mood perfectly, conveying that this albumis not going to be pretty, and that it may not be danceable, but canstill be compelling enough to want to know where the rapidlyaccelerating incantations are leading. "There's Always Room on theBroom" mixes distorted voices and fuzzed out samplers with a creepyfalsetto sing-a-long chorus that eats away at the defenses like amalevolent earworm until the song has completely seized control ofrational judgment and begins to appear on the mind at its own volition.Combined with the hysterical strobe-animation video included with thedisc, the song is a devious and extremely successful attempt atreprogramming listeners and viewers to find the unlistenablelistenable. "They Don't Want Your Corn, They Want Your Kids" is theclosest to the early Liars bass lines and kick beats, a brief reprievefrom the murky fear of tracks like "We Fenced Other Gardens With theBones of Our Own," with its desperate cry of "We're doomed! We'redoomed!" that pierces through the indiscriminate chanting aboutcauldrons and evil spells. These songs capitalize on the darkness andspooky atmosphere that were hinted at in earlier efforts that wereobscured by the snap of a dance-punk bass line, driving the band (andtheir audience) into more and more unfamiliar territory until much oftheir sound and style are unrecognizable. They Were Wrong, So We Drownedis a reactionary record, forged in the glare of the spotlight thrustupon the band in the wake of their catchy debut. Rather than linger inthe comfortable bed they made for themselves, and potentially reap thebenefits of a wider appeal, they chose to start from scratch andchallenge themselves. In the end, the adventurousness of this decisionwill benefit them far more, as Liars have demonstrated that they are acapable, inventive band with more than just one trick up their sleeves. Read More