- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Much like Brian Pyle’s Ensemble Economique project, Matt Hill’s Umberto guise often falls into a stylistic territory that I have a hard time connecting with. In Umberto's case, that territory is a sort of "retro soundtrack" vision informed by both '80s horror films and spaced-out '70s synth music. Both artists are equally capable of flooring me though and this latest release happily falls into the latter category at several points, as Hill took a more song-based and live instrumentation-driven approach this time around. Admittedly, the resultant stylistic transformation was exactly not an extreme one (or a consistent one), but it is sometimes just enough to push Helpless Spectator out of the Goblin/John Carpenter realm and into something closer to a killer space rock band wielding unconventional instrumentation. That is an extremely cool niche when it works, yet this album shines most brilliantly on the shadowy, synth-driven psychedelia of "Leafless Tree," which is an absolute goddamn masterpiece.

Much like Brian Pyle’s Ensemble Economique project, Matt Hill’s Umberto guise often falls into a stylistic territory that I have a hard time connecting with. In Umberto's case, that territory is a sort of "retro soundtrack" vision informed by both '80s horror films and spaced-out '70s synth music. Both artists are equally capable of flooring me though and this latest release happily falls into the latter category at several points, as Hill took a more song-based and live instrumentation-driven approach this time around. Admittedly, the resultant stylistic transformation was exactly not an extreme one (or a consistent one), but it is sometimes just enough to push Helpless Spectator out of the Goblin/John Carpenter realm and into something closer to a killer space rock band wielding unconventional instrumentation. That is an extremely cool niche when it works, yet this album shines most brilliantly on the shadowy, synth-driven psychedelia of "Leafless Tree," which is an absolute goddamn masterpiece.

It is hard to decide whether or not Helpless Spectator is a full-on concept album in its intent, but Hill borrowed the title from Julian Jaynes' controversial book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, which made a deep impact on him.Jaynes' book posits that the human mind used to be divided into two distinct halves: one which spoke and one which obeyed, but Hill was primarily fascinated by the idea that our consciousness might wrongly perceive itself as being in control when it actually is not.Obviously, such metaphysical concerns are fertile soil for a heady, deep-psych reverie and Hill and his consciousness fitfully do quite a fine job conjuring and sustaining that shadow world.Notably, he had some talented outside help for this album as well, almost making Umberto more like a band than a solo project (but not quite).His choice of collaborators was an intriguing and curious one, as he primarily worked with cellist/composer Aaron Martin (who also contributes bowed banjo).The duo are occasionally joined by Million Brazilians' "Idaho Joe" Winslow as well, who contributes pedal steel to a pair of songs.Given that Hill is very much a synth-focused fellow, that line-up results in a conspicuous absence of conventional rock instruments (though it should be noted that Hill is a damn good bassist when he wants to be).At times, that unusual palette can feel like a constraint, but Hill and Martin are quite an inventive duo that generally makes it work.

Despite the shift in both line-up and intent, however, there are still a number of pieces that sound like they could have been composed for film soundtracks.The enigmatic and brooding opener "Hidden Thoughts" is one such piece, but Hill made a conscious effort to move towards "warm, softer pads" with this release: the aesthetic is more ambiguous and meditative than sinister.If it was an actual soundtrack, Helpless Spectator would definitely fit an eerily atmospheric art film rather than giallo fare.The best piece in that more cinematic vein is the bittersweetly lovely closer "Arroyo," which marries warm strings with minimalist piano patterns and a languorously beautiful sliding guitar motif."Sadness, Happiness, Disgust, and Surprise" is also a noteworthy piece though, as it expectedly transforms from a dramatically melancholy neo-classical piece into a wild final act that sounds like a nightmarish prog jam.I suppose that is the "surprise" part and it was quite a delightful one, even if most of the piece felt a bit too melodramatic for my taste.Hill and Martin achieve a far more satisfying sort of exquisite melancholy later with the tender piano ballad "Absent Images," as the cello moans and swoons in all the right ways and a burbling synth motif adds a subtly hallucinatory veil that makes it all feel wonderfully dreamlike.The more striking pieces on the album tend to be the rhythm-driven ones though, particularly the swirling blow-out "Spontaneous Possession," which beautifully combines a thumping kick drum pulse with snaking flute melodies, a propulsive bass line, and roiling guitar chaos.The whimsically crunching and carnivalesque "Reflection" stands out as well, even if it does not evolve much beyond its beginnings.

The crown jewel of the album, however, is "Leafless Tree."At its core, it is a hauntingly subdued synth piece centered on a woozily spectral arpeggio theme.As it progresses, however, it becomes a slow-burning gem of simmering tension and tragic beauty, gradually fleshing out with moody smears of pedal steel and ringing synth tones.It is quite honestly one of the most achingly gorgeous synth pieces I have ever heard, which highlights a key trait of Matt Hill's work: he has the vision, instrumental prowess, and lightness of touch necessary to make some absolutely stunning and sublime music, but his erratic muse steers him in some curious and eclectic directions that are not always for me.As such, Helpless Spectator is a very strange mixed bag of an album, pulled in several different directions with varying degrees of success.Moreover, Hill's finest ideas are not always the ones that stick around the longest, which can be kind of exasperating.In particular, the outro of "Sadness, Happiness, Disgust, and Surprise" makes me hope that a director commissions Hill for such a lucrative film score that he is able to take a year off to assemble a killer band and focus entirely upon recording a scarily intense prog album (I plan to irrationally cling to that fantasy indefinitely).For now, however, Helpless Spectator is a masterfully polished and skillfully arranged hit-or-miss release that is legitimately dazzling on the occasions when it hits.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

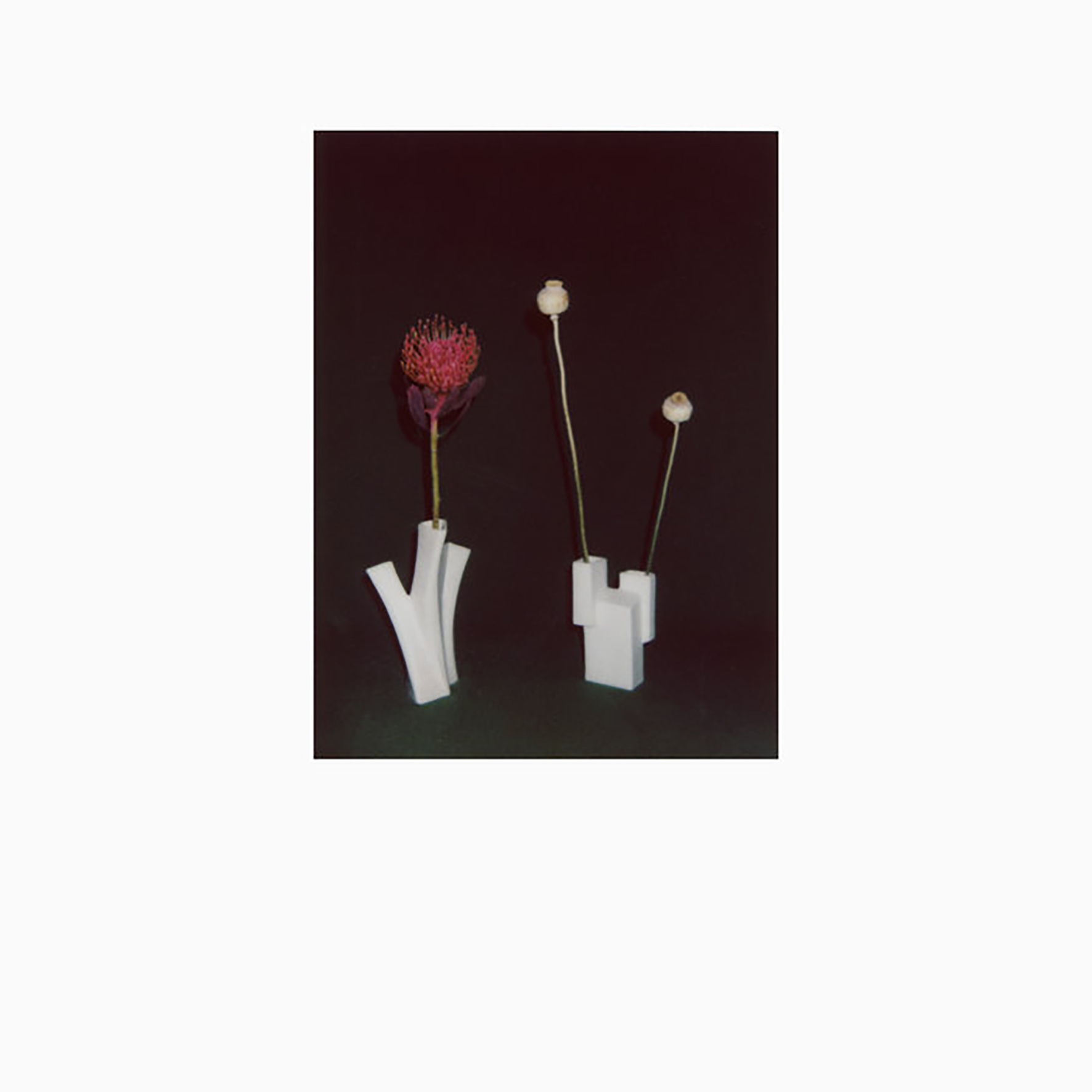

This latest album was composed and recorded in "impersonal hotel rooms in foreign cities" as Atkinson ambitiously toured the world while pregnant, making plenty of field recordings in far-flung locales like Tasmania and the Mojave Desert along the way. I am not surprised that those conditions were particularly amenable for her hushed, dreamlike, and ASMR-inspired vocal work, but I did not expect the underlying music to be quite as fleshed-out and hauntingly lovely as this. While Atkinson cites both Japanese flower arrangement and childhood memories of French impressionist composers as significant influences, her elegantly fragmented and floating reveries are uniquely and distinctively her own. I do wonder if the Ikebana influence was the final missing puzzle piece for Atkinson's artistic vision though, as The Flower And The Vessel strikes me as her strongest release to date. Her aesthetic has not changed all that much (nor would I want it to), but her intuitions for focus, clarity, and balance have definitely become stronger and more unerring.

This latest album was composed and recorded in "impersonal hotel rooms in foreign cities" as Atkinson ambitiously toured the world while pregnant, making plenty of field recordings in far-flung locales like Tasmania and the Mojave Desert along the way. I am not surprised that those conditions were particularly amenable for her hushed, dreamlike, and ASMR-inspired vocal work, but I did not expect the underlying music to be quite as fleshed-out and hauntingly lovely as this. While Atkinson cites both Japanese flower arrangement and childhood memories of French impressionist composers as significant influences, her elegantly fragmented and floating reveries are uniquely and distinctively her own. I do wonder if the Ikebana influence was the final missing puzzle piece for Atkinson's artistic vision though, as The Flower And The Vessel strikes me as her strongest release to date. Her aesthetic has not changed all that much (nor would I want it to), but her intuitions for focus, clarity, and balance have definitely become stronger and more unerring.

As befits an album quietly recorded with minimal equipment in hotel rooms, The Flower And The Vessel opens in subdued, enigmatic, and blearily soft-focus fashion.After a brief introduction ("L'Après-Midi") that is essentially just Atkinson's murmuring and whispering voice, the album begins in earnest with the shivering drones and rippling melancholy piano arpeggios of "Moderato Cantabile."It is quite a lovely and tender piece, but the lion's share of Atkinson's artistry is devoted to the textures and dynamics, as floating and swelling tones alternately crackle, sensuously throb, or hang in the air like a warm mist.It is not until the third piece ("Shirley to Shirley"), however, that the album truly catches fire.Musically, "Shirley" is an elegantly blurred and simmering bit of slow-motion psychedelia, as a languorous swirl of field recordings and synths floats above a lazily fluid bass line.The best part is the vocals though, as Atkinson shares a cryptic and confessional-sounding monologue that is multitracked and processed to sound eerily supernatural.From that point onward, The Flower And the Vessel blossoms into quite a quietly stunning album, as even a simple piece like "Un Ovale Vert" is a rapturous reverie of overlapping ripples and submerged snatches of evocative field recordings.

While "Shirley to Shirley" is never quite unseated as the release’s high-water mark, the second half of the album shows Atkinson to be an absolute sorceress at wielding slow-building tension and conjuring wonderfully disorienting and hallucinatory scenes."You Have To Have Eyes" is an especially striking and mesmerizing example of Atkinson's unique and creepy mystique, as her whispered monologue slowly builds to a dense web of buzzing textures, obsessively repeating loops, and snippets of a truly haunting child-like voice.It is a beguilingly fragile, intimate, and lovely piece that also makes me feel like I am about to be murdered by a demonic doll in an abandoned orphanage.Atkinson gamely allows those sinister shadows to deepen further with the murky and pointillist "Linguistics Of Atoms," but the gently dreamlike "Lush" steers the arc back towards beauty and human warmth, resembling a hypnotic and ritualistic gamelan performance under a starry desert sky.I quite like Atkinson’s "ASMR-damaged Fourth World dreamscape" aesthetic and it surfaces a few more times before the album ends, but the two pieces that diverge from it a bit are more noteworthy.The best is the achingly lovely and gently swaying "Joan," as a gorgeously woozy and wobbly organ theme slowly emerges from the quavering thrum of the opening collage (the chattering birds are a nice touch too).Atkinson's bleary and beautiful organ melodies return once more for the closing epic "Des Pierres," but it does not linger in sensuous, quavering warmth forever, as guest Stephen O'Malley helps build the piece to a roiling crescendo of pulsing guitar noise.

While it admittedly takes a few songs before The Flower And The Vessel begins to make a deep impression, it definitely makes one, as Atkinson pulled together quite a strikingly beautiful and seductively hallucinatory batch of songs."Shirley to Shirley" easily ranks among the finest pieces that Atkinson has ever recorded, but almost all of her recent albums have had least one rapturously sublime centerpiece.The difference with this one is merely that the gulf between "Shirley" and the surrounding material it is not a wide one at all: several of the songs on the last half of the album would have easily been stand-out pieces on any previous release.That said, they belong here and here alone.While the consistently high level of quality is a delight, The Flower And The Vessel is quite an impressive work as a focused, compelling, and immersive whole as well.The appeal transcends music, as it is closer to a hypnagogic, impressionistic travelogue of remote locales shared with quiet, tender intimacy.The Flower And The Vessel is Atkinson's defining masterpiece (and probably the single most beautiful and effective embodiment of the Shelter Press aesthetic as well).I love this album.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I definitely did not expect any more Black to Comm releases this year (or even next year), as composing and mixing the massive and wildly ambitious Seven Horses for Seven Kings likely kept Marc Richter very busy for a very long time. I woefully underestimated the volume of material birthed from that transcendent bout of inspiration though, as another album is already here and it is another great one. While the two albums originate from the same sessions, Before After is billed as a deliberately composed companion album rather than a collection of orphaned tracks. To my ears, however, it actually sounds like both (in a good way): given the exacting sequencing and arc of Seven Horses, it would make sense if a lot of great songs did not quite fit that particular vision. Most of these eclectic, stand-alone pieces are certainly strong enough to have made the cut for Seven Horses, but I am glad they ultimately wound up on Before After instead, as this album is closer to my preferred aesthetic of playfully experimental and hallucinatory collage.

I definitely did not expect any more Black to Comm releases this year (or even next year), as composing and mixing the massive and wildly ambitious Seven Horses for Seven Kings likely kept Marc Richter very busy for a very long time. I woefully underestimated the volume of material birthed from that transcendent bout of inspiration though, as another album is already here and it is another great one. While the two albums originate from the same sessions, Before After is billed as a deliberately composed companion album rather than a collection of orphaned tracks. To my ears, however, it actually sounds like both (in a good way): given the exacting sequencing and arc of Seven Horses, it would make sense if a lot of great songs did not quite fit that particular vision. Most of these eclectic, stand-alone pieces are certainly strong enough to have made the cut for Seven Horses, but I am glad they ultimately wound up on Before After instead, as this album is closer to my preferred aesthetic of playfully experimental and hallucinatory collage.

If I had any doubts about whether Richter had enough legitimately great material left over from the Seven Horses sessions for yet another strong album, they were completely erased within the first minute of the truly infernal "États-Unis."The core of the piece is a nightmarish, sickly swirl of choral voices that phantasmagorically reverberate and smear together into ugly harmonies.Richter eventually grounds that floating horror with some brooding chords, but I am not sure he needed to, as he had already achieved a wonderfully disturbing "ruined cathedral of the damned" feel.I particularly enjoyed the crunching industrial noises, the strangled feedback, and the wonderful interplay of the various textures quite a lot, which illustrates the defining character of Before After: these eight pieces feel like a freeform playground for fitfully brilliant and compelling inspirations rather than a suite of meticulously crafted compositions.The blurting, screaming chaos of the following "His Bristling Irascibility (Mirror Blues)" is the most extreme example of that tendency, resembling a hyper-caffeinated Nurse With Wound in exotica mode having a complete psychotic breakdown.Such chaos and cacophony is the exception rather than the rule though, as Richter soon returns to warped beauty with "They Said Sleep," inventively transforming an early medieval folk song into a grinding, howling, and mind-obliterating maelstrom of ravaged angelic derangement.The first side of the album then unexpectedly winds to a close with a lovely and subdued piano piece that has an endearingly lurching and tumbling rhythm that resembles out-of-phase loops rubbing up against one another.

The album's second half opens with "Eden-Olympia," a wonderfully roiling sea of rapidly hammered piano tones that slowly accumulates hallucinatory layers as it builds towards a reverberating percussion crescendo.In keeping with Before After's unpredictably phantasmagoric trajectory, the following "Othering" takes a deep plunge into pagan/ritualistic-sounding heavy psych that sounds like a sinister hurdy-gurdy ensemble (it calls to mind Cyclobe's amazing Derek Jarman soundtracks as well)."The Seven of Horses" follows suit in a very similar vein, but the strangled bagpipe-like drones are strafed by blurting, splattering electronic noise and whines that evoke a sky full of fireworks (or, less desirable: falling bombs).Both pieces are absolutely wonderful and among my favorites on the album, as Richter does a stellar job of blurring the illusion of an ancient and exotic imagined past with gleefully gnarled mindfuckery.The album ends on a more subdued and sublime note, however, as "Perfume Sample" repurposes material from Seven Horses into a weirdly mass-like outro of half-ghostly/half-anthemic chords.It is the least substantial piece on the album, but it is an interesting and effective closer sequencing-wise: it feels like a well-earned glimpse of transcendence at the end of a series of bizarre and deeply unsettling nightmares.

Amusingly, I feel a vague, low-level sense of guilt for liking this album as much as I do, as Richter's last few albums as Black to Comm have been very ambitious, focused, and sharply realized artistic statements.Before After does not quite fall into that category, as it seems like Richter simply had a bunch of cool ideas and just let them unfold organically without much concern for their role in the larger whole.Even the individual pieces do not feel particularly "composed," as each one is generally devoted to a single theme that just kind of starts and stops at whatever point feels natural.Given the strength and imagination of Richter's visions, that casual, unpolished brilliance works quite well and this album never feels indulgent or half-formed (nor does it feel overwrought, obviously).It favorably reminds me of LPD's "Chemical Playschool" series, but if they were mercilessly edited until only the best parts remained.It is clear that Richter devote quite a bit of time into shaping these fascinating soundscapes into a coherent album with a thoughtful arc, even if that arc feels like an elusively shapeshifting series of darkly hallucinatory fever dreams.It might not be a sweeping and panoramic epic like its predecessor or 2014's Black to Comm, but the more modest pleasures of Before After are definitely inspired enough to belong in that company (and they occasionally surpass it).

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I first encountered Joseph Allred on a massive compilation of American Primitive guitarists that I believe surfaced on the Dying For Bad Music blog sometime last year, but my ears must not have been working that week, as the experience did not leave a strong impression. In my defense, my ears were likely hopelessly numbed by the sheer volume of relatively similar (and often wonderful) artists who have worked in that vein over the years. John Fahey cast a long shadow and inspired a lot of dazzling instrumental performances, but the best compliment one can pay such an iconoclast is to use the American Primitive style as a mere starting point for a distinctive new vision. And if there is one thing Joseph Allred has (besides virtuosity), it is definitely vision, as O Meadowlark is an impressionistic suite of songs that abstractly chronicles the travails and ultimate transfiguration of Allred's alter-ego Poor Faulkner. Of course, there is a long tradition of storytelling among steel-string guitarists, as it adds some welcome depth and color to what could otherwise just be a mere display of instrumental prowess. To his credit, Allred is on an entirely different level in that regard, as his stories are singularly strange and unique ones and he channels them vividly. This is a fascinating release.

I first encountered Joseph Allred on a massive compilation of American Primitive guitarists that I believe surfaced on the Dying For Bad Music blog sometime last year, but my ears must not have been working that week, as the experience did not leave a strong impression. In my defense, my ears were likely hopelessly numbed by the sheer volume of relatively similar (and often wonderful) artists who have worked in that vein over the years. John Fahey cast a long shadow and inspired a lot of dazzling instrumental performances, but the best compliment one can pay such an iconoclast is to use the American Primitive style as a mere starting point for a distinctive new vision. And if there is one thing Joseph Allred has (besides virtuosity), it is definitely vision, as O Meadowlark is an impressionistic suite of songs that abstractly chronicles the travails and ultimate transfiguration of Allred's alter-ego Poor Faulkner. Of course, there is a long tradition of storytelling among steel-string guitarists, as it adds some welcome depth and color to what could otherwise just be a mere display of instrumental prowess. To his credit, Allred is on an entirely different level in that regard, as his stories are singularly strange and unique ones and he channels them vividly. This is a fascinating release.

I have historically not placed too much importance on the stories behind albums by solo guitarists, as my attitude has always been that I am only interested in the inspiration behind a song once I already like it (it rarely works in the opposite direction).In the case of Joseph Allred, however, it is impossible to separate his instrumental work from his larger and more complex vision.Central to that vision is the character of Poor Faulkner, whom Allred describes as "a character I sometimes tell stories about in my music, or....assume his perspective and play songs from there."On the surface, Poor Faulker is a fairly modest invention as far as mythic alter-egos are concerned: "He's a very lonely middle aged man who lives in a house in a remote part of Tennessee. He thinks the house is haunted."Thankfully, things get much better for him over the course of these six songs.That said, O Meadowlark was originally recorded over the course of a single night with no overarching vision in mind, yet a coherent narrative emerged to Allred when he listened back to what he had done.In a poetic and abstract way, the song titles provide a window into that arc, but the essence is that Poor Faulkner is lured into the woods by a bird, experiences two angelic visitations, and ultimately ascends to heaven.Absent from this album is a channeling of the vision that the angel shows Poor Faulker before his ascension, but that will apparently be the basis for a future album.As is probably quite clear from the album's premise, Allred has an intense passion for religion, arguably resembling a kind of Appalachian David Tibet.In fact, I will be surprised if the two artists do not eventually collaborate in some way.The pair certainly have a deep affinity, as Allred has performed the Methodist hymn "Idumea" in the past, which he first encountered through Current 93.

Notably, Allred did not become fully devoted to the acoustic guitar until around 2011 (as a means for coping with a family crisis).Before then, he was involved with a series of eclectic noise, ambient, and drone projects, as well as some relatively heavy Tennessee-based rock bands.That eclectic background, as well as his deep interest in Indian drone music, has no doubt informed Allred's guitar work in some curious and inscrutable ways.While it is impossible to draw a linear path from his many divergent interests to O Meadowlark, it is clear that Allred has a very unique approach to structure and composition.In fact, I would describe this album as "post-structure," albeit in a good way: there are no structured chord progressions, no predictably recurring themes, no consistent melodies, and no rigid tempos.Instead, the melodies and the chords unfold in an organic and spontaneous way.I suppose that is what people normally call "improvising" and it may very well be that, but Allred's previous album was much more tightly composed and conventionally melodic.Consequently, it has to have been a deliberate choice to leave that behind in favor of O Meadowlark's more fluid approach.That said, there are a number of structured melodic passages throughout the album, particularly on the more banjo-driven works like the title piece and the Eastern-tinged "The Porch at Night."Such frameworks rarely remain in place for the duration of an entire song, however, as Allred has a tendency to build towards explosive crescendos of rapidly picked notes.The sounds are very much in the tradition of Basho and Fahey, but Allred's approach owes just as much to Coltrane’s sheets of sound as it does to his fellow six-stringers.

After hearing O Meadowlark, I immediately picked up 2016’s similarly excellent Fire & Earth and found it to be quite a different experience.In some ways, that album is a significantly stronger one, as the individual pieces are more memorable and distinct from one another.Also, I very much appreciated the occasional harmonium and vocal interludes, as they broke up the sequencing nicely.If O Meadowlark has a flaw, it is that the six songs flow together as a constantly shifting whole rather than asserting their own identities.That is presumably by design, however, and partially illustrates where O Meadowlark truly shines: it is a large-scale work and a major creative leap forward, deftly manipulating dynamics to remain compelling for over forty minutes without any repeating hooks or flourishes that recall the work of other artists.Aside from definitively establishing a unique voice, O Meadowlark is a masterclass in balance and fluidity, as Allred seamless moves from languorous oases of sweep-picked chords to impassioned eruptions of tremolo-picked intensity in an eternal ebb and flow.Those flurries of passion are one of the other major reasons O Meadowlark is such a striking release in an overcrowded milieu: this is not a guitar album–this is an album in which an artist uses a guitar in an attempt to convey the beauty, sadness, and mystery of life in his own modest way.Every aspect of this release is rooted in a deep sincerity and a desire to make art that is human and meaningful and it shows.There are plenty of great guitarists in the world, but not many of them manage to turn their art into such an honest and direct self-portrait as this one.

Samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Emptyset, the duo of James Ginzburg and Paul Purgas, are tireless innovators at the vanguard of electronic music. Over the course of the last decade the duo have consistently applied new and inventive compositional tools to create art that is both unique and poignant. Blossoms focuses on ideas of evolution and adaptation, bringing together Emptyset's body of exploratory sound production with emerging methods of machine learning and raw audio synthesis.

The machine learning system for Blossoms was developed through extensive audio training, a process of seeding a software model with a sonic knowledge base of material to learn and predict from. This was supplied from a collection of their existing material as well as 10 hours of improvised recordings using wood, metal and drum skins. This collection of electronic and acoustic sounds formed unexpected outcomes as the system sought out coherence from within this vastly diverse source material, attempting to form a logic from within the contradictions of the sonic data set. The system demonstrates obscure mechanisms of relational reasoning and pattern recognition, finding correlations and connections between seemingly unrelated sounds and manifesting an emergent non-human musicality.

While intensely researching and developing the parameters for Blossoms, Emptyset's members have remained pillars in the communities of art and audio. James Ginzburg released two acclaimed solo releases in the last year, and runs the Subtext label (which recently released Ellen Arkbro's Chords), and additionally runs the Arc Light Editions imprint with Jen Allan. Paul Purgas recently presented a lecture on the history of India’s first electronic music studio at Guildford International Music Festival’s Moog Symposium, curated Wysing Arts Centre’s annual music festival with Moor Mother and wrote for the Unsound:Undead book for Audint (distributed by MIT Press). Since the release of their 2017 album Borders, the duo has been collaborating with highly specialized programmers and engaging with emerging theoretical research to devise a system architecture that would be evolved enough to establish the foundations for their album. Emptyset have continued to evolve the project into more performative frameworks as well, which will culminate in a series of live performances including the initial realization’s debut at Unsound Festival in Krakow, Poland.

Blossoms is a work built on hybrids and mutations, combining complexly synthesized audio with reverbs derived from impulses taken in architectural sites Emptyset have worked in previously. The assembled compositions are emblematic of Emptyset's dedication to forward-looking sound and examine patterns of emergence and augmentation, fragmentation and resilience, and the convolution of biotic and abiotic agency.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

After years of mythology, misinterpretation and procrastination, Nurse With Wound’s Steven Stapleton finally chooses Finders Keepers Records as the ideal collaborators to release "the right tracks" from his uber-legendary psych/prog/punk peculiarity shopping list known as The Nurse With Wound List, commencing with a French-specific Volume One of this authentically titled "Strain Crack Break" series. Featuring some Finders Keepers' regulars amongst galactic Gallic rarities (previously presumed to be imaginary red herrings) this deluxe double vinyl dossier demystifies some of the essential French free jazz and Parisian prog inclusions from the alphabetical "dedication" inventory as printed in the anti-band's 1979 industrial milestone debut.

When Steven Stapleton, Heman Pathak and John Fothergill's anti-band Nurse With Wound decided to include an alphabetical dedication to all their favorite bands on the back of their inaugural LP, the notion of creating a future record dealers' trophy list couldn't have been further from their minds. By adding a list of untraveled European mythical musicians and noise makers to their own debut release of unchartered industrial art rock, they were merely providing a suggestive support system of existing potential like-minded bands, establishing safety in numbers should anyone require sonic subtitles for Nurse With Wound's own mutant musical language. Luckily for them, the record landed in record shops in the midst of 1979's memorable summer of abject apathy and its sound became a hit amongst disillusioned agit-pop pickers and artsy post-punks, thus playing a key role in the burgeoning "Industrial" genre that ensued. For the most part, however, the list–like most instruction manuals–remained unreadable, syntactic and suspiciously sarcastic… As potential "real musicians," Nurse With Wound became an Industrial music fan's household name, but in contrast many of the names on The Nurse With Wound List were considered to be imaginary musicians, made-up bands or booby traps for hacks and smart-arses. It took a while for the rest of the record collecting community to catch on or finally catch up.

Since then, many of the rare, obscure and unpronounceable genre-free records on The Nurse With Wound List have slowly found their own feet and stumbled in to the homes of open-minded outernational vinyl junkies, DJs and sample-hungry producers, self-propelled and judged on their own merit, mostly without consultation of the enigmatic NWW map. But, to the inspective competitive collector’s chagrin, one resounding fact recurs: NWW got there first! via vinyl vacations, on cheap flights and Interrail tickets, buying bargain bin LPs on a shoestring while oblivious to the pending pension-worthy price tags after their 40 year vintage. Stapleton and Fothergill, even if you've never heard of them, were at the bottom of the pit before "digging" became paydirt. And NOW at huge international record fairs that occur in massive exhibition halls (or within the confines of your one-touch palm pilot) amongst jive talk acronyms such as SS, PP, BIN, DNAP and BCWHES the coded letters NWW have begun to appear on stickers in the corner of original copies of the same premium progressive records accompanied by a customary 18% price hike to titillate/coerce the initiated as dealers extort the taught. Like "psych" "PINA" or "Krautrock" did before, "NWW" has become a buzzword and in the passed decades since its first publication The List has been mythologized, misunderstood and misconstrued. Its also been overlooked, overestimated and under-appreciated in equal measures, but with a growing interest it has also come to represent a maligned genre in itself, something that all members of the original line-up would have deemed sacrilegious. Bolstered by the subtitle "Categories strain, crack and sometimes break, under their burden," all bands on the inventory (many chosen on the strength of just one track alone) were chosen for their genre-defying qualities… A check-list for the uncharted.

Forty years after Nurse With Wound’s first record, Finders Keepers Records, in close collaboration with Steven Stapleton remind fans of THIS kind of "lost" music–that there once existed a feint path which was worn away decades before major label pop property developers built over this psychedelic underground. As long-running fans and liberators of some of the same records, arriving at the same axis from different-but-the-same planets, Finders Keepers and Nurse With Wound finally sing from the same hymn sheet, resulting in a collaborative attempt to officially, authentically, and legally compile the best tracks from the list, succeeding where many overzealous nerds have deferred (or simply, got the wrong end of the stick). Naturally our lavish metallic gatefold double vinyl compendium would only scratch the surface of this DIY dossier of elongated punk-prog peculiarities, hence our decision to release volume one in a series which, in accordance with Steve's wishes, focuses exclusively on individual tracks of French origin, the country that unsurprisingly hosted the highest content of bands on the list. Comprising of musique concrète, free jazz, Rock In Opposition, Zeuhl School space rock, macabre ballet music, lo-fi sci-fi, and classic horror literature-inspired prog, this first volume of the series entitled "Strain Crack And Break" throws us in at the deep end, where the Seine meets the in-sane, introducing the space cadets that found Mars in Marseilles.

Like the Swedish flat-pack record shelves that attempt to house the vast amounts of vintage vinyl that goes into a multi-volume compilation like this, it is time to prepare your own musical penchants and preconceived ideas about DIY music and hear them slowly strain, crack and break.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

шон means "Poles" in Mongolia dialect.

It is the first and it will be certainly the only one album from Otto Solange.

"I’ve decided in 2019 to release some of the pieces of works recorded from 2013 to 2015 to leave an imprint from this period and give a life to an other side of my sound works, more unknown by people who follow my other sound projects (Monolyth & Cobalt, D-Rhöne).

I've traveled a lot at this time and also, this period was precisely at the middle of a great change in my life. My son was born at the end of 2015 and a big part of these works have been recorded for him, with probably some memories from my previous journeys around the world."

"All have been composed and recorded at home with a set of many electronic hardwares and no laptop (samplers, effects and loops). Using some various samples from my music collection library as a collage process and some other sounds have been recorded from a part of my solo instruments and electronics machines."

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

"Who are we when we're alone?"

The simplest questions are often the most difficult to answer. In April of 2018, Drowse's Kyle Bates left his home in Portland, OR for an artist residency in barren northern Iceland. Much of Bates' time there was spent in self-imposed isolation, giving him ample space to ponder the nature of solitude, and what it means to be "closed" or "open" to the world. Upon returning home, Bates worked obsessively. Maya Stoner, a longtime creative partner, sometimes came to sing, but recordings where mostly done alone. The dichotomy of his Icelandic musings materialized in a very real way as he neglected his personal relationships in favor of his art. While he was confronting his life-long fear of intimacy, and reconciling himself to a diagnosis of Bipolar 1, Bates found that the means he employed to conquer these obstacles–self reflection through art–carried with them an equal measure of misery. Light Mirror, Drowse's second album for The Flenser, is a subtle exploration of these contradictory attitudes and their consequences that can be heard as an artifact of sonic self-sabotage.

Light Mirror falls within a lineage of overcast Pacific Northwest albums (think Grouper's Dragging a Dead Deer Up a Hill), but finds Drowse pushing past its slowcore roots. The album's prismatic sound reflects experimental electronic, noise pop, black metal, krautrock, and more through Kyle's distinct song-worlds. The lyrics are ruminations on the idea of multiple selves, identity, paranoia, fear of the body, alcohol abuse, social media, the power of memory, the truths that are revealed when we are alone, and the significance of human contact. They were influenced by filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky and poet Louise Glück, who both address self-contradiction. Mastered by Nicholas Wilbur (Mount Eerie, Planning for Burial) at the Unknown, the album showcases a striking maturation in sound. Light Mirror is Drowse's most intimate and desolate work to date.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

In his solo work and as a member of Nine Inch Nails, Alessandro Cortini's music casts the listener into an intricately rendered vortex of emotive dynamics, where he expertly maximizes the boundaries of contemporary electronic music. His new album, Volume Massimo, combines his fondness for melody with the rigour of experimental practice. Follows on from 2017's universally acclaimed album Avanti. 8 tracks of deftly arranged synthesizers saturated with sonic artefacts and luscious pop sensibilities.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

On Sutarti, Joshua Sabin draws influence from the compositional structures and psychoacoustic properties that exist within early Lithuanian folk music, exploring the emotional potency of the human voice through the manipulation of elements of archival recordings.

Obtaining access to the folk music archives of the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre Ethnomusicology Archive from the outset of this project, Sabin felt a particular resonance with the extensive library of vocal recordings and specifically the song forms of the Sutartinė. Derived from the Lithuanian verb "Sutarti" - to be "in agreement," "to attune" – Sutartinės are a Lithuanian form of Schwebungsdiaphonie - a distinct canonic song style consisting of two or more voices that purposefully clash creating extremely precise dissonances and the phenomena of aural ‘beating’.

Inspired by the psychoacoustic research of Rytis Ambrazevičius, whose computer analyses reveal the unique acoustic and harmonic complexities in these archival songs, and transfixed by what Sabin describes as their "arresting and often almost plaintive and minimalistic beauty," he sought to compose directly with the recordings themselves as a raw material.

Sutarti exists fundamentally as an emotional "response," presenting archival voices through radical recontextualizations that Sabin hopes simultaneously express both his personal perspective and experience, and also speak universally to the power and versatility of the voice as a communicator of meaning and emotion.

Produced with archival recordings, instrumentation including, Skudučiai and Fiddle, and field recordings of Lithuanian forest ambiences.

Joshua Sabin is an Edinburgh based composer and sound designer, who’s first LP Terminus Drift was released on Subtext in 2017.

Done as part of the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision's RE:VIVE initiative in collaboration with the Lithuanian Archivist's Association and the Baltic Audiovisual Archival Council

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

After a trilogy of spectacular explorations of relentlessly driving rhythms – Sagittarian Domain (2012), Quixotism (2014) and Hubris (2016) – Simian Angel finds Oren Ambarchi renewing his focus on his singular approach to the electric guitar, returning in part to the spacious canvases of classic releases like Grapes from the Estate while also following his muse down previously unexplored byways.

Reflecting Ambarchi's profound love of Brazilian music – an aspect of his omnivorous musical appetite not immediately apparent in his own work until now – Simian Angel features the remarkable percussive talents of the legendary Cyro Baptista, a key part of the Downtown scene who has collaborated with everyone from John Zorn and Derek Bailey to Robert Palmer and Herbie Hancock. Like the music of Nana Vasconcelos and Airto Moreira, Simian Angel places Baptista's dexterous and rhythmically nuanced handling of traditional Brazilian percussion instruments into an unexpected musical context. On the first side, "Palm Sugar Candy," Baptista's spare and halting rhythms wind their way through a landscape of gliding electronic tones, gently rising up and momentarily subsiding until the piece's final minutes leave Ambarchi's guitar unaccompanied. While the rich, swirling harmonics of Ambarchi's guitar performance are familiar to listeners from his previous recordings, the subtly wavering, synthetic guitar tone we hear is quite new, coming across at times like an abstracted, splayed-out take on the 80s guitar-synth work of Pat Metheny or Bill Frisell. Equally new is the harmonic complexity of Ambarchi's playing, which leaves behind the minimalist simplicity of much of his previous work for a constantly-shifting play between lush consonance and uneasy dissonance.

Beginning with a beautiful passage of unaccompanied percussion dominated by the berimbau, the side-long title piece carries on the first side's exploration of subtle, non-linear dynamic arcs, taking the form of a gently episodic suite, in which distinctive moments, like a lyrical passage of guitar-triggered piano, unexpectedly arise from intervals of drifting tones like dream images suddenly cohering. In the piece’s second half, the piano tones becomes increasingly more clipped and synthetic, scattering themselves into aleatoric melodies that call to mind an imaginary collaboration between Albert Marcoeur and David Behrman, grounded all the while by the pulse of Baptista's percussion. Subtle yet complex, fleeting yet emotionally affecting, Simian Angel is an essential chapter in Ambarchi's restlessly exploratory oeuvre.

More information can be found here.

Read More