- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Keeping up with Benjamin Finger’s tireless work ethic in recent years has been an increasing challenge for me, but it has been a worthwhile one, as he manages to maintain a consistently high level of quality and sometimes surprises me with an especially inspired detour or two. Also, his trail of recent releases is not unlike a fun scavenger hunt, leading me from one cool small-press label to another. In the case of Into Light, that small-press label is Berlin’s Forwind and the album is a solid example of Finger's warmly hallucinatory dronescape aesthetic. Pleasure-Voltage, on the other hand, falls into the "inspired detour" category, as Finger debuts an unexpectedly muscular trio with avant-garde violinist Mia Zabelka and extreme music super-producer James Plotkin. The latter album, released on another Berlin label (the eclectic and adventurous Karlrecords), is the more significant by virtue of being unlike anything else in Finger’s discography, but both releases have their share of bright moments.

Keeping up with Benjamin Finger’s tireless work ethic in recent years has been an increasing challenge for me, but it has been a worthwhile one, as he manages to maintain a consistently high level of quality and sometimes surprises me with an especially inspired detour or two. Also, his trail of recent releases is not unlike a fun scavenger hunt, leading me from one cool small-press label to another. In the case of Into Light, that small-press label is Berlin’s Forwind and the album is a solid example of Finger's warmly hallucinatory dronescape aesthetic. Pleasure-Voltage, on the other hand, falls into the "inspired detour" category, as Finger debuts an unexpectedly muscular trio with avant-garde violinist Mia Zabelka and extreme music super-producer James Plotkin. The latter album, released on another Berlin label (the eclectic and adventurous Karlrecords), is the more significant by virtue of being unlike anything else in Finger’s discography, but both releases have their share of bright moments.

Forwind/Karlrecords

Into Light is composed of two long pieces and two short pieces that all fall within Finger's signature terrain of vibrantly textured, shimmering, and melodic psych-collages.Unsurprisingly, it is the more focused, shorter pieces that make the strongest first impression.They arguably make the strongest lasting impression as well, but that is less clear-cut.The opening "A Glimpse" admittedly feels like more of an introduction than a stand-alone piece, but Finger whips up quite an impressively churning and roiling mass of heavy drones and buried harmonies.It is the melodic and comparatively straightforward synth-based title piece that is the album's achingly gorgeous centerpiece though."Into Light" is an uncharacteristically simple and linear composition by Finger standards, but that approach suits the material quite well: a lovely progression of warm chords slowly unfolds in a dreamlike haze of floating harmonies and subtly reality-bending effects.It is a perfectly crafted piece from start to finish, as its strong central theme feels wonderfully pure and undiluted, yet the shifting smears of sound around it stealthily provide layers of harmonic depth and textural nuance.As great as "Into Light" is, however, it is the album's longer pieces that showcase the idiosyncratic vision that makes Finger such a consistently intriguing and distinctive artist."Gravity's Jest" and "Paradox Route" are the sort of fare that one can only find on a Benjamin Finger album.

Initially, "Gravity’s Jest" feels like an uncharacteristically dark and neo-classical piece, as guest cellist Elling Finnanger Snøfugl provides a somber and slow-moving central melody.I suppose that brooding and melancholy theme is arguably the heart of the piece, yet it would be more accurate to describe it as the soil from which Finger's production magic slowly blossoms.By the halfway point, the focus has been deftly shifted away from the groaning strings, as they have become just one component in a shape-shifting fantasia of fluttering, shuddering, buzzing, and bleary aural phantoms. In fact, all traces of that initial theme are long gone when the final movement creeps into being, as the outro is classic sundappled Benjamin Finger-style psychedelia: a billowing, soft-focus swirl of angelic vocal fragments mingling with radiant washes of synthesizer.Into Light's other epic is the lush, swooning ambient haze of "Paradox Route," which weaves a gorgeous, fragile web from Inga-Lill Farstad’s cooing, breathy vocal loops.It would be a perfect piece if it just stayed in that pleasantly delirious and quivering heaven without ever building towards anything more substantial or structured, but build and evolve it does.Still, Finger largely manages to maintain his precarious spell as the mood darkens and the mournful cello returns to lead the way into a surreal miasma of subtly kinetic psych-flourishes. The album's only real weakness is that the heavier moods are not a seamless fit with the lightness, warmth, and playfulness of Finger's bittersweet dreamscapes.When he is at his best, Finger evokes the beautiful innocence of hazy childhood memories like no one else, but it takes a masterful lightness of touch to maintain that illusion.While Finger manages that feat for a few sustained stretches on Into Light, only the title piece does it well enough to rank among his strongest work.

Samples can be found here.

While it is roughly rooted in the same aesthetic terrain as Into Light, Pleasure-Voltage marks an intriguing evolution for Finger, as he enlisted a pair of well-chosen collaborators to run roughshod over his delicate impressionist reveries.Given their historic predilections for heavier, more abrasive sounds, neither Mia Zabelka nor James Plotkin would have ever sprung to mind as likely kindred spirits for a Finger-led ensemble, yet this unlikely trio assembled nonetheless and debuted with a performance at 2018’s REWIRE festival.As befits its unusual collision of disparate aesthetics, the album itself has an unusual structure and origin: Finger composed the framework of Pleasure-Voltage himself, then passed it on to his collaborations to work their chaos-magic.To their credit, neither Zabelka nor Plotkin unleashed a visceral firestorm, gamely adapting their harsher tendencies to Finger's more understated aesthetic instead.That said, I suspect very little of the original structure survived the resultant transformations, as Pleasure-Voltage feels considerably more improvised and unpredictable than Finger's usual soundscapes.It has the spontaneity and life of a live improvisation, but the underlying structure enables these two pieces to feel like the best of both worlds, as the controlled maelstrom repeatedly gives way to reveal sublime oases of melody and harmonic depth.It feels kind of like a crackling electromagnetic cloud is drifting across Finger's warbly, sensuous soundscapes, occasionally allowing processed, childlike voices or a snatches of tender piano melodies to briefly emerge from the entropy only to be soon consumed once more.

Both pieces are too shifting and elusive to allow for simple descriptions, but the opening "Hostile Structures" seems to have a lovely, reverb-soaked piano motif at its heart.It becomes increasingly warped, lysergic, and disrupted as the piece unfolds, however, and it is impossible to tell what any of the individual artists is doing at any given point (all are credited with electronic manipulations of some kind).Near the end, Zabelka briefly unleashes a stuttering and strangled storm of electric violin, but that crescendo is quickly sucked into an even larger crescendo that feels like a howling black hole.Somehow a buried, party-rocking groove emerges from the wreckage, however, and the piece closes with an almost "space rock" outro fighting through a sheen of crackle and static.Initially, "Kaleidoscopic Nerves" is not all that different in tone, but it has a more linear arc, steadily building from bubbling, hazy drones to a low-level grinding and churning intensity.The bottom completely drops out around the midpoint though, and all structure dissolves in a swirling, buzzing haze of floating dissonances.Gradually, a fresh structure slowly comes together for a beautiful final stretch of swooping strings and quavering ambient warmth.I suppose those last few minutes of "Kaleidoscopic Nerves" are the only time Pleasure-Voltage quite flirts with brilliance, but I very much enjoy this trio’s general aesthetic and chemistry.Given the caliber of the participants, I did not expect this resemble any other Benjamin Finger albums and it did not disappoint me in that regard.However, it was still quite a pleasant surprise to find that it did not resemble anything else that I have heard either.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This latest project from FaUSt guitarist/Ulan Bator founder Amaury Cambuzat has regrettably been under my radar for the last several months, but AmOrtH recently caught my attention by virtue of its Dirter Promotions imprimatur. Prior to this latest release, Cambuzat had been documenting his amazing solo guitar "cathedral sessions" throughout the year with a series of videos that culminated with April's Rec.Requiem album (released on Italy's Dio Drone). If I had heard Rec.Requiem first, i am sure it would have floored me, as Cambuzat is an almost supernaturally brilliant drone artist. Instead, I encountered this one, which worked out quite well: AmOrtH is somehow even better than its predecessor. I have not heard drone as mesmerizingly heavy and ritualistic as this since I was blindsided by Natural Snow Buildings a decade ago. AmOrtH is an absolute monster of an album.

This latest project from FaUSt guitarist/Ulan Bator founder Amaury Cambuzat has regrettably been under my radar for the last several months, but AmOrtH recently caught my attention by virtue of its Dirter Promotions imprimatur. Prior to this latest release, Cambuzat had been documenting his amazing solo guitar "cathedral sessions" throughout the year with a series of videos that culminated with April's Rec.Requiem album (released on Italy's Dio Drone). If I had heard Rec.Requiem first, i am sure it would have floored me, as Cambuzat is an almost supernaturally brilliant drone artist. Instead, I encountered this one, which worked out quite well: AmOrtH is somehow even better than its predecessor. I have not heard drone as mesmerizingly heavy and ritualistic as this since I was blindsided by Natural Snow Buildings a decade ago. AmOrtH is an absolute monster of an album.

It is always an extremely good sign when I put on an album and my first thoughts are "where on earth did this come from?" and "how the hell is he doing this?". After a week of listening to AmOrtH, I am still stumped by the first question and I suspect any answer to the second would feel hopelessly inadequate. Simply put, Cambuzat conjures up incredibly rich and heavy dronescapes with just a guitar, the sound of a heartbeat, and a battery of effects. What he does with that simple palette verges on sorcery, however, particularly on the album's title tour de force. At the heart of "AmOrtH" is a sustained drone that feels like it is quaveringly alive–even if nothing else happened at all, that sustained note would be compelling solely from the improbable degree of intensity that Cambuzat wrings from it. Thankfully, that is just the start of his wonderfully deepening and irresistible spell. Even from its earliest moments, "AmOrtH" sounds like a barely controlled storm of howling noise over a slow pulse of processed heart beats. The sheer vibrancy and power of the sounds hits me the hardest of the piece's many wonderful attributes, as "AmOrtH" feels like it is slowly twisting and burning even as it steadily accumulates more force and density. Moreover, Cambuzat manipulates dynamics and wields tension beautifully, as there is never a lull or misstep in the piece's 40-minute ascension. Instead, the roiling noise slowly and subtly blossoms into a harmonically rich fantasia of shifting organ-like tones. It does not quite feel like a bombed cathedral, but it feels admirably close: it sounds like hell boiling out up from the earth in the middle of an organ mass. Words like "ecstatic" and "rapturous" spring readily to mind and "AmOrtH" earns them, but religious transcendence rarely (if ever) comes in such blackened and gnarled form.

Unexpectedly, however, that darkness slowly dissipates and the final third of "AmOrtH" is a warmly beautiful swirl of rippling and shimmering heaven. It is quite an impressive sleight-of-hand and all the more so since Cambuzat manages to do it without sacrificing any of the piece's power and majesty. It is far from a toothless bliss, as an undercurrent of rumbling, burning wreckage ensures that the idyll never stops feeling like a precarious and threatened one. The elegant balance of light and dark is particularly beautiful, akin to watching a lovely sunrise ascend over a landscape of smoldering ruins. In the wake of that heaving and scorched transfiguration, the album's shorter second piece ("Psalm 39") emerges as a sublime coda of sorts. It is considerably less ambitious than "AmOrtH," but it makes for a lovely and appropriate come-down, languorously taking shape as a shimmering reverie of slow, elegantly blurred guitar swells. It reminds me a bit of classic Stars of the Lid, as Cambuzat attains a similar degree of radiant, glacially evolving tranquility. By default, it is the weaker of the two pieces, but its most damning shortcoming is merely that it vaguely resembles someone else's great work rather than feeling like a dazzling eruption of iconoclastic brilliance.

When I initially read this album's description, I was a bit surprised to see The Theatre of Eternal Music boldly name-checked as the closest reference point, but that legitimately seems like the only logical antecedent for this project. Times have certainly changed since the '60s, so AmOrtH has zero chance of making the cultural impact of La Monte Young's revolutionary ensemble. The two projects definitely strain heavenward in similar ways though and neither feels like it shares anything in common with the contemporary drone genre beyond the name. When I Feel Like A Bombed Cathedral is at its best, it genuinely feels like a channeling, a trance state, or a religious experience, achieving an immersive and hypnotic majesty that approaches the ecstatic.   In fact, AmOrtH most strongly reminds me of Sufi whirling dervishes, as their ceremonial spinning meditations have a deep and spiritual purpose, yet they have the outward appearance of a unique and beautiful dance to non-participants. Similarly, I Feel Like A Bombed Cathedral appears to be a deeply personal and ritualistic endeavor that doubles as incredibly striking and powerful art. Both of I Feel Like A Bombed Cathedral's albums feel like the transcendently brilliant work of a drone savant, but AmOrtH's extended title piece alone captures that vision at its sustained and slow-burning zenith. This album is a masterpiece.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

English guitarist Andy Cartwright's A House With Too Much Fire was one of the most striking and underappreciated albums of 2018, beautifully evoking a timeless and haunted-sounding strain of Americana. For his follow-up, the expectant father arguably allows a bit more light to creep into his vision, but plunges still deeper into the more experimental and atmospheric tendencies that made Too Much Fire so wonderful. In fact, Crossing sheds many of the more overt folk trappings of its predecessor, largely replacing the banjos and acoustic guitars with drones from a bowed resonator guitar (though the "Haunted Americana" sensibility remains very firmly in place). Despite its strong emphasis on mood and sustained tones, it would be a mistake to characterize Crossing as anything like a conventional drone album though, as Cartwright's closest kindred spirit at this stage of his career seems to be Richard Skelton. It does not quite resemble the actual Richard Skelton though–instead Crossing often approximates an alternate Skelton who veered towards increasingly warm, intimate, and bittersweet soundscapes rather than embracing the deeper themes and elemental power of the natural world. I certainly have ample room in my heart for both directions, especially when executed this masterfully.

English guitarist Andy Cartwright's A House With Too Much Fire was one of the most striking and underappreciated albums of 2018, beautifully evoking a timeless and haunted-sounding strain of Americana. For his follow-up, the expectant father arguably allows a bit more light to creep into his vision, but plunges still deeper into the more experimental and atmospheric tendencies that made Too Much Fire so wonderful. In fact, Crossing sheds many of the more overt folk trappings of its predecessor, largely replacing the banjos and acoustic guitars with drones from a bowed resonator guitar (though the "Haunted Americana" sensibility remains very firmly in place). Despite its strong emphasis on mood and sustained tones, it would be a mistake to characterize Crossing as anything like a conventional drone album though, as Cartwright's closest kindred spirit at this stage of his career seems to be Richard Skelton. It does not quite resemble the actual Richard Skelton though–instead Crossing often approximates an alternate Skelton who veered towards increasingly warm, intimate, and bittersweet soundscapes rather than embracing the deeper themes and elemental power of the natural world. I certainly have ample room in my heart for both directions, especially when executed this masterfully.

I was pleasantly amazed when I first learned that Crossing was primarily composed for guitar (albeit an unconventionally played one), as the opening title piece feels very convincingly like the work of a full string quartet.I knew that it was possible to approximate a violin with a bowed guitar, but Cartwright somehow manages to conjure up the richly woody and rattling moans of a double bass as well.That textural wizardry and attentive devotion to sound design is a large part of what makes Seabuckthorn such a compelling project these days, as Cartwright is a master at finding the perfect balance between the ghostly and the visceral.Moreover, he applies those production talents to a distinctive, immersive, and bleakly beautiful vision.For me, that vision evokes clouds slowly rolling across the horizon of a desolate prairie in the 1800s.Consequently, I was also surprised to find that Crossing was composed in the French Alps, as it genuinely feels like it was dreamed up on the back porch of a ramshackle cabin in Joshua Tree by a grizzled hermit plagued by religious visions.That sense of stark, lonely beauty pervades much of the album and provides its ostensible center, as the darkly churning strings of the opener are reprised for two more movements of a "Crossing" trilogy (as well as the brooding coda of the closing "Crossed").Along the way, however, the clouds occasionally part to reveal some gorgeously sublime oases of flickering light and deep emotion.Those moments are where Crossing shines the brightest.

By my count, there are three absolute stunners among Crossing's fourteen songs: "To Which the Rest Were Dreamt," "The After Quiet," and "It Can Ashen."In "The Rest Were Dreamt," pulsing feedback-like harmonics form a slow, tender melody while fading in and out of focus like ghosts."The After Quiet" takes a similarly pulsing approach to melody, but beautifully tweaks the formula by adding a shivering, squealing, and undulating layer of bowed strings.On "It Can Ashen," on the other hand, a sleepily lovely clarinet melody endlessly repeats like an enigmatic bird song over a densely churning bed of heavy drones.There is also a second tier of excellent pieces that are quite striking as well, such as "The Cloud and the Redness," which nicely embellishes its slow-moving drones with vibrantly squeaking and squirming bowed strings that slice through the ambient haze.The mournful, banjo-driven "Cleanse" is yet another wonderful piece, though it is a bit of an outlier that returns to the territory of A House With Too Much Fire.To my ears, its slow-motion, rustic country blues is a dark horse candidate for Crossing's most inspired and revelatory piece, even if it is not the album's strongest composition.It feels like God himself had a bit too much whiskey, got all melancholy, and decided to play some sad bottleneck slide guitar on his porch.The playing itself is not particularly god-like, but the scale certainly feels like it, as Cartwright's sliding chords feel glacial and immense in a way that is not human.It is both weirdly meditative and eerily hallucinatory and it resembles nothing else that I have ever heard.

Even though some of the most achingly gorgeous moments on A House With Too Much Fire were the more abstract ones, I did not expect Cartwright as far away from the virtuosic fingerpicking of his early work as he does with this release.He is a hell of a gifted guitarist, yet anyone who encounters Seabuckthorn for the first time with Crossing could certainly be forgiven for not realizing that there were guitars on it.I suppose that makes Crossing a culminating achievement of sorts, as Cartwright has now definitively transformed from a guitarist with a flair for the cinematic into a gifted composer who is chasing a sublime and hauntingly impressionist vision (and succeeding).In that regard, Cartwright continues to roughly mirror the trajectory of his former label mate William Ryan Fritch: both are talented multi-instrumentalists increasingly in demand for film scores and both have a pronounced fondness for a evoking a mythic American West. Their sole major divergence is that Fritch is far more prolific and stylistically varied (and that he makes it seem effortless).Cartwright, on the other hand, seems like the sort of artist who will spend years devotedly straining to attain the one vision that obsesses him.In both cases, the end result is the same: plenty of excellent music and an occasional glimpse of almost unearthly beauty.When Cartwright is at his best (as he sometimes is here), it feels like he is on an entirely different plane than most other composers.I am not sure if Crossing necessarily surpasses Too Much Fire or merely maintains the same level of greatness, but it does not matter: both albums fitfully capture an incandescent brilliance that can rarely be found elsewhere.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Newcomer Zoe Reddy joins Phantom Limb for the release of her stunning debut EP Machine, a fascinating middle ground between avant-R'n'B and experimental music. A uniquely styled and fully-formed initial offering, Machine represents a new artist with clear vision and identity.

Named after and inspired by the rhythmic qualities of everyday motorized objects, Machine acts as a soundtrack to the 21st century life in which we are so surrounded by and immersed in technology as to become deaf to its sounds. Captivated by this constant generation of non-musical sounds, Reddy recorded washing machines, blenders and other motorized objects about the house to form rhythmic foundations to her songs. Using these starting points, the record took shape as a meeting point of electro-acoustic sound processing, electronic production, and Zoe's love of dance music.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Two years in the making, Angel in the Detail is an enthralling & captivating release where distinctive vocals & lyrical imagery float over textural ambience, hypnotic guitar, synth washes & spellbinding bass pulses.

Out August 23rd on Metropolis. More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Neurot Recordings are proud to reissue the landmark collaboration Neurosis & Jarboe, which was originally released in 2003, incoming on 2nd August. This latest version is fully remastered and with entirely new artwork from Aaron Turner, available on vinyl for the first time, as well as CD and digital formats.

Steve Von Till explains the idea behind the remastering; "Bob Weston (Chicago Mastering Service, and member of Shellac) worked closely with Noah on making these new versions sound as good as the possibly can. Noah has the most trained critical ear for fidelity out of all of us being an engineer himself. We recorded this ourselves with consumer level Pro Tools back then, in order to be able to experiment at home in getting different sounds and writing spontaneously. The technology has come a long way since then and we thought we could run it through better digital to analog conversion and trusted Bob Weston to be able to bring out the best in it....This new mastered version is a bit more open, with a better stereo image, and better final eq treatment."

When two independent and distinct spheres overlap, the resulting ellipse tends to emphasise the most striking and powerful characteristics of each body. Such is the case with this particular collaboration between heavy music pioneers Neurosis and the multi-faceted performer Jarboe (who performed in Swans and who has collaborated with an array of people from Blixa Bargeld, J.G. Thirlwell, Attila Csihar, Bill Laswell, Merzbow, Justin K. Broadrick, Helen Money, Father Murphy, the list goes on...) The musicians pull from one another some of the most harrowing and unusual sounds ever heard from either artist at the time - a sentiment which also rings true to some 15 years later.

The collaboration is a deeply textured mosaic that is a culmination of merged aesthetics from two major influences on free-thinking sounds. It unlocked the hidden potential of electronic music as a new force in heavy rock. At a time when groups like Oneida, Wolf Eyes and Black Dice were beginning to experiment with technology in making mind-numbing leaden electro-drone freed from any essence of "dance music," Neurosis & Jarboe redefined all notions of their past - and outlined the course of heavy music to come.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Post-metal sludge avant garde powerhouse SUMAC follow their collaboration with legendary Japanese guitarist and singer/performer Keiji Haino on Thrill Jockey (American Dollar Bill – Keep Facing Sideways, You are too Hideous to Look at Face on) with another monolith.

Keiji Haino – Guitar, Voice, Flute, Taepyeongso

Aaron Turner – Guitar

Nick Yacyshyn – Drums

Brian Cook – Bass

Out June 28th on Trost.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Vanishing Twin is songwriter, singer and multi-instrumentalist Cathy Lucas, drummer Valentina Magaletti, bassist Susumu Mukai, synth/guitar player Phil MFU and visual artist/film maker Elliott Arndt on flute and percussion; and on this album they have made their first artistic statement for the ages.

Some of its great power comes from liberation. The album was produced by Lucas in a number of non-standard, non-studio settings. "KRK (At Home In Strange Places)," which summons up the spirit of Sun Ra's Lanquidity and Broadcast And The Focus Group Investigate Witch Cults Of The Radio Age, was simply recorded on an iPhone during a live set which crackled with psychic connectivity on the Croatian island of Krk.

The magical Morricone-esque lounge of "You Are Not an Island," the blissed-out Jean-Claude Vannier style arrangement of "Invisible World" and burbling sci-fi funk ode to a 1972 cult French animation, "Plane te Sauvage," were all recorded in nighttime sessions in an abandoned mill in Sudbury. The only two outsiders to work on the recording were "6th member" and engineer Syd Kemp and trusted friend Malcolm Catto, band leader of the spiritual jazz/future funk outfit The Heliocentrics, who mixed seven of the tracks (with Lucas taking care of the other three).

Vanishing Twin formed in 2015 - their first LP, Choose Your Own Adventure, which came out on Soundway in 2016; followed by the darker, more abstract, mostly instrumental Dream By Numbers EP in 2017.

The band explored their more experimental tendencies on the Magic And Machines tape released by Blank Editions in 2018, an improvised session recorded in the dead of night, offering a glimpse into their practice of deep listening, near band telepathy, and ritually improvised sound making. These sessions formed the basis of The Age Of Immunology.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

There's something about the Swedish city of Malmo that doesn’t add up.

Named the "happiest" city in Sweden in 2016 (who gets the job of judging these things?), Malmo's DNA contains a "none-coding" strain that reveals the city's penchant for a world more studious, fashioned in a vintage era, telescoped by pop culture that arrives via the TV-approved bridge that connects it to Denmark. Surely, it can’t be the same place.

Marleen Nilsson, Magnus Bodin and Anders Hansson of Death and Vanilla couldn't come from anywhere else. They are dreamers, antiquarians, music-obsessed individuals, lauded by the media for their last album To Where The Wild Things Are from 2015…

"Swedish exponents of dreamily lovely psych and lush, late-60s-style baroque pop." The Guardian

"Lush and enveloping, reminiscent of Curt Boettcher and Margo Guryan." The Wire

"Fantastically eerie." Clash

The trio's love of all things "old" is well known – they've tinkled ivories, played vibraphone, recorded with a Sennheiser microphone and a nod to everything from Fun Boy Three to Orchestre Poly Rythmo de Contonou, while still roaming somewhere between an ambient Eno and Cocteau Twins at a late-night soiree.

Prior to recording their new album Are You A Dreamer?, they scored several soundtracks, that process undoubtedly influencing the new album's dreamlike euphoria built with added mellotron and affected electric guitar. Expanded with bass and drums in their quest for the grail, Death And Vanilla's songs are longer; more plush and pampered; more hypnotic and haunting.

Are You A Dreamer? is melancholy at its most refined, riddled with super-memorable motifs and melodies that nestle in reflective echo. Death And Vanilla are an alluring confection, hard to resist and wantonly moreish as Marleen Nilsson’s sepia tones are embraced by the trio’s gorgeous arrangements and intricate ambience.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Umberto is an artist whose work is distinctly cinematic. Composer Matt Hill's performances and delicate compositions taken together have the cumulative ability to surprise. Hill, whose Umberto moniker is an homage to director Umberto Lenzi, is an experienced and active film composer, most recently scoring the film All That We Destroy. In addition to film and commercial work, Umberto has released a number of lauded solo recordings. Hill's compositions stand apart as beautiful as they are impenetrable, with pulsing synths that hint at 80s slasher films while pensive string passages evoke emotions without being sentimental. On Umberto's Thrill Jockey debut Helpless Spectator, his haunting music is otherworldly and affecting alike, leaving the listener with an unsettling and profound air of mystery.

Umberto's early recordings harken back to classic synth-driven sci-fi and horror soundtracks. Helpless Spectator uses synthesizers in an entirely different manner. Cold, looming monolith tones are now warm, softer pads that envelope the listener while guitar, cello, banjo and pedal steel add movement and light. Still, Hill unsettles with his arrangements and melodic phrasing. As a composer, Hill has moved to more extensive use of live instrumentation. In addition to playing guitar, bass, and piano himself, Hill worked with fellow composer and recording artist Aaron Martin who played cello and bowed banjo on the majority of the album. "Idaho Joe" Winslow’s pedal steel guitar adds depth and subtle countermelodies to "The Higher Room" and "Leafless Tree."

The name Helpless Spectator is taken from the Julian Jaynes book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Hill was taken with the concept Jaynes set out to disprove that "Consciousness can no more modify the working mechanism of the body or its behavior than can the whistle of a train modify its machinery or where it goes." The darkness and obliviousness inherent in this concept, the notion that while we perceive control, we are not in control, serves as a great metaphor for the contrasts of Umberto's music. Warm tones and nuanced arrangements with cello and pedal steel are not typically the instruments of dread, yet Hill achieves a creeping undertone of dread with his deceptively complex pieces. Musical figures both melodically and rhythmically simple intertwine, build, and collapse upon one another. The dissonant tensions that steadily grow rarely completely resolve; rather they dissipate into a new set of questions. Unexpected shifts and turns in even the most tender movements of Helpless Spectator are inflected with a contemplative melancholy and fragility.

Umberto makes masterful use of varied textures throughout the album, blending supernatural effects and grounded instruments to create distinct atmospheres. Helpless Spectator is inquisitive and moving in equal measure, an album of somber elegance and delicate arrangements whose cumulative effect of unease is entirely unexpected.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

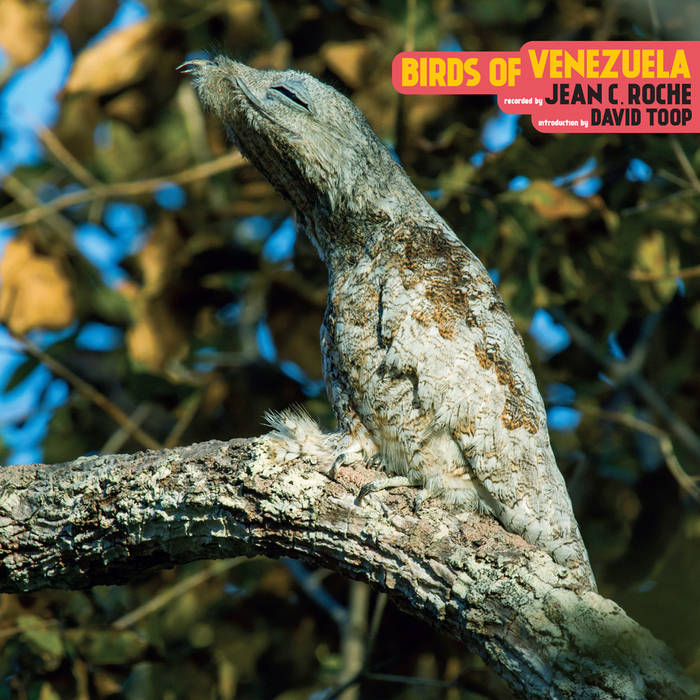

This unusual reissue quietly entered the world last December when everyone was frantically obsessing over the year-end lists and features, so it did not get nearly the attention it deserved. It is certainly an odd release for a couple of reasons, but the most obvious one is that a 35-year-old album of bird songs was resurrected by a record label best known for avant-garde and experimental music. The other is that Birds of Venezuela was just one of over one hundred albums recorded and released by French ornithologist Jean-Claude Roché. That naturally begged the questions "What makes this album the special one?" and "Who exactly is this for?". As it turns out, the liner notes by David Toop answer the former and the album itself decisively answered the latter: this album is for me because it is amazing. In fact, Toop actually started planning a trip to the Amazon soon after hearing this Birds of Venezuela and I probably would have done the same, as a strong case could be made that the most texturally and melodically compelling music scene of the mid-‘70s was the Venezuelan rain forests.

This unusual reissue quietly entered the world last December when everyone was frantically obsessing over the year-end lists and features, so it did not get nearly the attention it deserved. It is certainly an odd release for a couple of reasons, but the most obvious one is that a 35-year-old album of bird songs was resurrected by a record label best known for avant-garde and experimental music. The other is that Birds of Venezuela was just one of over one hundred albums recorded and released by French ornithologist Jean-Claude Roché. That naturally begged the questions "What makes this album the special one?" and "Who exactly is this for?". As it turns out, the liner notes by David Toop answer the former and the album itself decisively answered the latter: this album is for me because it is amazing. In fact, Toop actually started planning a trip to the Amazon soon after hearing this Birds of Venezuela and I probably would have done the same, as a strong case could be made that the most texturally and melodically compelling music scene of the mid-‘70s was the Venezuelan rain forests.

Given that this is an album of field recordings of birds, it is no surprise that the birds themselves are the stars.Among the many participants, the pootoo portrayed on the album’s cover is the biggest draw of all, as the liner notes breathlessly describe it as "a metal-looking bird" that is "one of the sonorous curiosities of this mad nature."Toop himself encountered the pootoo's song on his own Venezuelan trip and described it as "like lost ghost-souls crying out to the living" and one of the "most affecting" listening experiences of his life.With source material like that, Birds of Venezuela certainly would have been a fitfully striking release as just a collection of pure field recordings, but it is actually elevated to a higher plane of art and vision by Roché's unusual collage approach to mixing.Unlike many bird-based albums, Roché’s intention was not to document and isolate the individual songs.Rather, he ambitiously attempted to create a vivid and vibrantly alive "stereo concert" that roughly replicated the experience of being inside the delightful cacophony that erupted every dusk and dawn in Venezuelan forests.Amusingly, Roché unintentionally became an actual avant-garde artist a few years later, as the Lyon-based GMVL started presenting evening events where they would play five of Roché's stereo concerts at once in a park.Depending on one's location in the park, it was possible to experience a blurring together of sounds from various continents at once.Jazz musicians soon began approaching Roché to tell him that they liked his work.I expect most ornithologists do not experience that level of fame in art scenes.

Each of the five pieces assembled here has its own distinct character and subtly surprisingly trajectory.For example, the opening "Ocumare" initially sounds exactly like what I would expect from an album of Venezuelan bird songs, then unexpectedly erupts into a bubbling and hallucinatory crescendo with the help of a chorus of frogs.In "Gran Saba," one especially singular bird call that I recognized from a Dead Can Dance album stands out, but the depth and the warbling, seesawing dynamics of the backdrop are perhaps even more compelling (until it is all enveloped by the sinister roar of howler monkeys, anyway).The shorter "Rancho Grande" revisits that immersive, multilayered sound field of chittering, gibbering, and chirping sans monkeys, acting as a palette-cleanser of sorts before than album's bizarre and memorable second half.As a composition, the lengthy "Palmar" is arguably the album’s zenith, as it undergoes a mesmerizing and surreal transformation that strikingly feels industrial or futuristic at times.Naturally, Roché saves the pootoo's appearance for last, as their haunting call sneakily creeps up through the otherwise happy chirping and gurgling of "Guanare/Barinas."Toop's description of the sound as "ghost-souls" is a fairly apt one, as the pootoo's call does have an eerily human sound, albeit one that sounds smeared and processed.To my ears, it is not necessarily more attention-grabbing than the album's previous frog eruptions, but it is deliciously unnerving in its context.It feels like Roché presents a lively, colorful, and playful swirl of sounds, then stealthily pulls back a curtain to reveal the darker and more disturbing reality that also exists in the Amazonian rain forests.

One element of truly great music that I am always chasing is a masterful feat of illusion that erases any overt traces of deliberate compositional arc, recognizable instrumentation, rigid chord structure, or the hand of the artist.I did not expect to find such a perfect example of that achievement here, as I have heard plenty of bird-song albums before and I have never been particularly dazzled by them.Roché's stereo concerts, however, elevate a chorus of isolated pretty sounds into a trilling, chirping symphony of genuine depth and textural genius.Many years ago, I got to experience a Francisco López piece that was essentially processed rain forest sounds played with maniacal intensity and crushing volume.Unsurprisingly, it was an amazing and overwhelming experience.Birds of Venezuela is every bit as compelling as that, albeit a far more subdued variation: "birds as ambient soundscape" rather than "birds as noise assault."As a pure musical experience, this album is a virtuosic masterclass in dynamics and layering, as there a vibrant mélange of constant movements, shifting distances, loop-like rhythms, and melodic unpredictability pervading all these pieces.I know nothing about bird and frog psychology, so I have no idea how much the individual participants on this album consciously interact with other species sound-wise.They all seem to have a very important role that complements the roles of others though: Birds of Venezuela is like hearing a vast improv ensemble operating on a hive-mind level and it feels both effortless and transcendent.

Samples can be found here.

Read More