- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

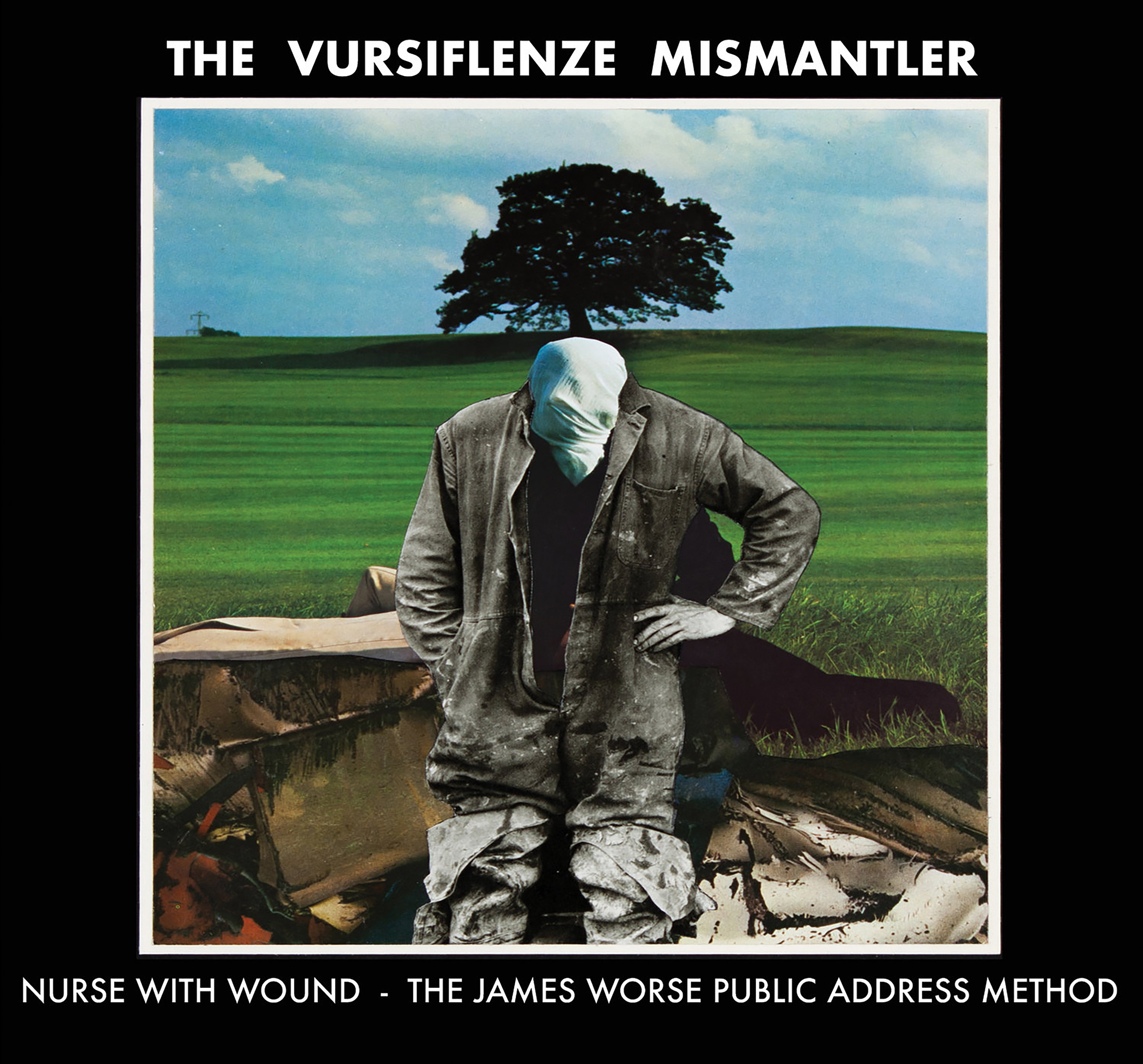

Cover art by Babs Santini.

Back cover art... could be Worse.

A complete new studio album on United Dairies (UD913).

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

"Co-habitant treads on most sensitive melodic nerves in their exquisite debut and sole release for Chained Library.

The eponymous Co-habitant release trades in a distinct style of filigree, pealing, high-register electronic minimalism that uses sparse ingredients to absorbingly meditative effect.

The A-side’s swaying figure in "a.003" is a particular highlight that we could easily listen to on loop for hours, while the B-side has us utterly rapt with the transition from mechanical rhythmelody and fascinating reverberant overtones in "b.002" thru the isolationist SAW II tingles of "b.003" and the sallow ripples of "b.004.""

-via Boomkat

Additional information can arguably be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

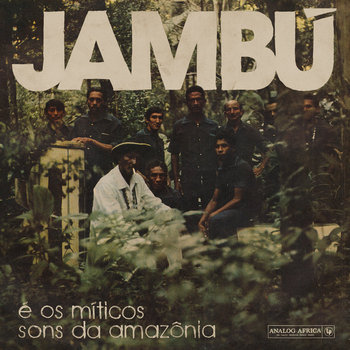

The city of Belém, in the Northern state of Pará in Brazil, has long been a hotbed of culture and musical innovation. Enveloped by the mystical wonder of the Amazonian forest and overlooking the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean, Belém consists of a diverse culture as vibrant and broad as the Amazon itself. Amerindians, Europeans, Africans - and the myriad combinations between these people - would mingle, and ingeniously pioneer musical genres such as Carimbó, Samba-De-Cacete, Siriá, Bois-Bumbás and bambiá. Although left in the margins of history, these exotic and mysteriously different sounds would thrive in a parallel universe of their own.

I didn't even know of the existence of that universe until an Australian DJ and producer by the name of Carlo Xavier dragged me deep into this whole new musical world. Ant it all began in Belém do Pará. Perched on a peninsula between the Bay of Guajará and the Guamá river, sculpted by water into ports, small deltas and peripheral areas, Belém had connected city dwellers with those deeper within the forest providing fertile ground for the development of a popular culture mirroring the mighty waters surrounding it. Through the continuous flow of culture, language and tradition, various rhythms were gathered here and transformed into new musical forms that were simultaneously traditional and modern.

Historically marginalized African religions like Umbanda, Candomblé and the Tambor de Mina, which had reached this side of the Atlantic through slaves from West Africa – especially from the Kingdom of Dahomey, currently the Republic of Benin – left an indelible stamp on the identity of Pará's music. They would give birth to Lundun, Banguê and Carimbó, styles later modernised by Verequete, Orlando Pereira, Mestre Cupijó and Pinduca to great effect. The success of these pioneers would create a solid foundation for a myriad of modern bands in urban areas.

Known as the "Caribbean Port," Belem had been receiving signal from radio stations from Colombia, Surinam, Guyana and the Caribbean islands - notably Cuba and the Dominican republic - since the 1940s. By the early 1960s, Disc jockeys breathlessly exchanged Caribbean records to add these frenetic, island sounds to liven up revelers. The competition was fierce as to who would be the first to bring unheard hits from these countries. The craze eventually reached local bands' repertoires, and Belém's suburbs got overtaken by merengue, leading to the creation of modern sounds such as Lambada and Guitarrada.

To reach a larger audience, the music needed to be broadcast. Radios began targeting the taste of mainstream audiences and played music known as "music for masses". As the demand for this music grew, it led to the establishment of recording companies. Belém's infant recording industry began when Rauland Belém Som Ltd was founded in the 1970s. It boosted a radio station, a recording studio, a music label and had a deep roster of popular artists across the carimbó, siriá, bolero and Brega genres.

Another important aspect in understanding how the musical tradition spread in Belém, are the aparelhagem sonora: the sound system culture of Pará. Beginning as simple gramophones connected to loudspeakers tied to light posts or trees, these sound systems livened up neighbourhood parties and family gatherings. The equipment evolved from amateur models into sophisticated versions, perfected over time through the wisdom of handymen. Today's aparelhagens draw immense crowds, packing clubs with thousands of revelers in Belém's peripheral neighbourhoods or inland towns in Pará.

The history of Jambú e Os Míticos Sons Da Amazônia is the history of an entire city in its full glory. With bustling nightclubs providing the best sound systems and erotic live shows, gossip about the whereabouts of legendary bands, singers turned into movie stars, supreme craftiness, and the creativity of a class of musicians that didn't hesitate to take a gamble, Jambú is an exhilarating, cinematic ride into the beauty and heart of what makes Pará's little corner of the Amazon tick. The hip swaying, frantic percussion and big band brass of the mixture of carimbó with siriá, the mystical melodies of Amazonian drums, the hypnotizing cadence of the choirs, and the deep, musical reverence to Afro-Brazilian religions, provided the soundtrack for sweltering nights in the city's club district.

The music and tales found in Jambú are stories of resilience, triumph against all odds, and, most importantly, of a city in the borders of the Amazon who has always known how to throw a damn good party.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Debut release by the new ANTIGRAVITATIONAL imprint, the record label & multimedia platform created and curated by My Cat Is An Alien (MCIAA), set up with gallerist and publisher Marco Contini.

"MCIAA PHASE THREE — WE BAPTIZE THE SPIRITUAL NOISE" reads Roberto Opalio’s aesthetics Manifesto: SPIRITUAL NOISE opens the third decade of activity by iconoclastic instantaneous composers, musicians, performers and visual artists Maurizio and Roberto Opalio.

Fully focused on MCIAA’s "aliencentric" vision, Antigravitational’s main purpose is to offer the experience of the deepest immersion in the sound and visual matter of each work of intermedia art by the brothers–as duo, as soloists, as well as in collaborations with some of the most talented artists of our time.

Pursuing their ongoing fight against the digital-only fruition of concepts and contents of today, MCIAA privilege the thingness of physical mediums to fix their art, aiming to survive the non-permanence over time.

Designed following principles of seriality and of installation art, each release takes the shape of a multimedia object which displays a proper artbook mounted on the LP cover jacket, and gives access to cinematic poetry films and extra contents as further investigations. Various combinations of objects and formats are intended to provide an ever-expanding universe of multistratified references and meanings.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Live in Tokyo is a series of 11 distinct interpretations of the 1941 song "Skylark" by Johnny Mercer and Hoagy Carmichael performed by the quartet consisting of Orlando Lewis on clarinet, Franz-Ludwig Austenmeiser on keyboards, Hayden Pennyfeather on bass, and Roland Spindler on drums. This fact is anything but obvious upon listening, however. Based on the sound alone, it sounds more like an intimate series of improvisations rather than interpretations of a popular song from the 1940s, which was, I am sure, the performers' intent. It may bear some resemblance to its source material, however the quartet manage to create something nearly entirely original.

Live in Tokyo is a series of 11 distinct interpretations of the 1941 song "Skylark" by Johnny Mercer and Hoagy Carmichael performed by the quartet consisting of Orlando Lewis on clarinet, Franz-Ludwig Austenmeiser on keyboards, Hayden Pennyfeather on bass, and Roland Spindler on drums. This fact is anything but obvious upon listening, however. Based on the sound alone, it sounds more like an intimate series of improvisations rather than interpretations of a popular song from the 1940s, which was, I am sure, the performers' intent. It may bear some resemblance to its source material, however the quartet manage to create something nearly entirely original.

They are anything but frequent, but there are moments across the 70 minutes of this album where there are clues that the quartet is interpreting a piece of traditional music.The second segment has some apparent clarinet and bass appearing in the mix, but the performance is almost excruciatingly slow, crawling along with the focus equally split between the instruments and the incidental sounds between.The fifth section also features up front clarinet and bowed bass, as well as an almost didgeridoo like sound appearing later on, but is still only musical in the loosest interpretation of the word.

Part six also has some apparent notes being played, augmented by a thumping, unconventional rhythm that mixes things up a bit.Knocking rhythms also pop up throughout the third part, with vibrating bass strings being the only other conventional sound in the mix.The remainder is a series of blowing and wheezing noises that are likely associated with the clarinet, but it is hard to say for sure.For the tenth piece, restrained and slow melody can be heard again, but just like the second part, it slowly trudges along.

The rest of the album comes across as even less musical and more conceptual in its deconstruction of the song.The opening part exemplifies this via the abrupt incidental clattering and empty space captured by the recording device.Eventually Pennyfeather's bass appears in the form of infrequently plucked strings and a bit of static crunch from Austenmeiser's keyboards, but the focus is obviously on the empty space.The nearly 20 minute seventh part is also a clearly more conceptual one.Random clattering sounds again open with sparse bass notes, weird clarinet squeaks by Lewis, and strange rhythmic noises via Spindler.Throughout it sounds like everyone spends a good portion of the time playing their instruments incorrectly (and I mean this as a complement), and even a bit of jarring outbursts of who knows what to punch into the mix.What stands out though, besides the intentional unconventionality, is the detail of the recording, which captures every little sound perfectly.

Extremely conceptual by design, Live in Tokyo is a strange recording to say the least.Even though it is ostensibly a long form interpretation of that original "Skylark" song, I would only know that due to the liner notes.Based solely on the recording, however, it is a challenging and complex bit of art that is intricately detailed, and the quartet's performance is beautifully captured.Baffling and confusing at times, the obtuseness of Live in Tokyo is what I found the most compelling about the disc.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Billed as a companion piece to 2018's stellar Impossible Star, Opaque Couché continues Meat Beat's recent hot streak with a double album packed with inventive and meticulously crafted dance music virtuosity. Given that Jack Dangers' work has passed though quite a succession of different phases over the years, Impossible Star is indeed Opaque Couché's closest reference point, yet the two albums go in significantly different directions within their roughly similar stylistic territories (and only this one pays homage to one of the world's ugliest colors). Whereas its predecessor embraced the feel of an inhuman and paranoid sci-fi dystopia, Opaque Couché takes that futuristic bent in much more playful and propulsively kinetic direction. Naturally, it all sounds great, as Dangers is a singularly exacting producer. His true genius, however, lies in how seamlessly he is able to mash together high art, deadpan kitsch, and vibrantly infectious drum loops. Admittedly, that has been true for quite a long time, but he seems to creep closer and closer to achieving the perfect balance with each new release.

Billed as a companion piece to 2018's stellar Impossible Star, Opaque Couché continues Meat Beat's recent hot streak with a double album packed with inventive and meticulously crafted dance music virtuosity. Given that Jack Dangers' work has passed though quite a succession of different phases over the years, Impossible Star is indeed Opaque Couché's closest reference point, yet the two albums go in significantly different directions within their roughly similar stylistic territories (and only this one pays homage to one of the world's ugliest colors). Whereas its predecessor embraced the feel of an inhuman and paranoid sci-fi dystopia, Opaque Couché takes that futuristic bent in much more playful and propulsively kinetic direction. Naturally, it all sounds great, as Dangers is a singularly exacting producer. His true genius, however, lies in how seamlessly he is able to mash together high art, deadpan kitsch, and vibrantly infectious drum loops. Admittedly, that has been true for quite a long time, but he seems to creep closer and closer to achieving the perfect balance with each new release.

The album opens on a deceptively creepy note, as "Untroduction" cultivates a palpable sense of impending menace with its gnarled, sweeping synth drones and cryptic samples from a psychological experiment.Unexpectedly, however, it segues into a killer party rather than bleakly futuristic alienation, as "Pin Drop" unleashes quite an amazing variation on the classic "amen break." Musically, Dangers and Ben Stokes flesh out their brilliantly clattering groove with a deep bass line, some blurrily surreal chords, and a ghostly melody, but none of those elements are the real focus.The hyper-kinetic drumming is the heart of the piece and everything else is mere icing on the cake.In fact, "Pin Drop" fondly reminds me of all of the times I have been wandering around a city and stumbled upon an insanely virtuosic and funky drummer going absolutely bananas in a park or square.The beat itself is a familiar one, of course, yet Dangers and Stokes keep it fresh and wild with a vibrant array of fills.There are also some occasional surprises like the fleeting intrusion of a toasting MC that add nicely to the sense that the whole thing is about to careen off the rails at any second.It never does, of course, but does a glorious job of riding that line til the very end.Wisely, the duo refrain from ever trying to repeat the same magic formula, but they do return to Jungle-style break beats a couple more times with fresh twists.On the more nervous-sounding "No Design," for example, the frenetic snares are augmented by disorienting swirl of robotic, chopped, and stuttering voices."Critical Soul Vibrations," on the other hand, sounds geared for the dancefloor: the robot voices feel more like hooks and there are some fairly musical and jazzy vocal samples that provide welcome human warmth.

The rest of the album can roughly be divided into two categories that are best described as "robot funk" and "minimalist electronic jazz," though there are a handful of detours into brooding atmospheric vignettes, brief synthesizer experiments, and more industrial-minded fare scattered about.Some of the more polished and jazz-influenced pieces admittedly leave me cold, but highlights improbably come from every one of those directions at least once.Meat Beat's "robot funk" side is perhaps best represented by the lumbering groove and squirming, sputtering electronics of "CarrierFreq," which also features a weirdly poignant hook of a digitized voice lamenting "I don’t know what to say, I don’t know what to do."A far more unlikely pleasure is "Forced to Lie," which marries blurred and warped jazz chords with a trip-hop beat…and a repeating loop of Wolfman Jack addressing some "birdbrains."Elsewhere, a thumping house beat relentlessly propels the wonderfully jabbering and gurgling synths of "Present For Sally," while Dangers' distorted and deconstructed "rapping" adds an unpredictable and texturally vibrant splash of color to an insistent, industrial-damaged pulse in "[Ear-Lips]."Meat Beat's jazzier side offers some pleasures as well, though that side tends to work best when its smoothness it counterbalanced by erratic, deranged-sounding synth patterns (which is the happily the case in "Call Sign").Without that element of chaos, the jazzier touches walk a precariously fine line between endearingly woozy "space age bachelor pad" sounds and something that I could easily imagine getting licensed for a fashion runway show.For the most part, however, I very much appreciate the sophisticated approach to harmony on the album.There is a lot of underutilized ground between straight-up major and minor chords and Meat Beat are unusually adept at exploiting it (as far as electronic music artists are concerned, anyway).

It is worth noting that Meat Beat Manifesto have been releasing albums for thirty years at this point, yet Impossible Star was the first MBM album to fully connect with me.That does not necessarily mean that it towers above the rest of their oeuvre, though it is a truly excellent album.Instead, Dangers' work has always been an omnipresent outlier for many of my own phases, forever hovering around the "now" sound of electronic music, yet always too eclectic and off-center to fully fit.With these last two albums, however, it feels like Meat Beat has reached an unusual creative plateau where they are no longer in the thrall of the zeitgeist.Nevertheless, Dangers' long history in the trenches of underground dance music's evolution has left him singularly skilled at tossing off constant seamless allusions to its varying styles.Due to that, this album manages to feel fresh and contemporary even while veering off in its own occasionally backwards-looking direction.That freewheeling and sometimes mischievous eclecticism is probably what defines Opaque Couché the most, as it is a kaleidoscopic mélange of styles improbably held together by a predilection for retro-futurism, unusual sample juxtapositions, and production perfectionism.These pieces vary quite a bit from one another, but they never feel like they do not belong together.Moreover, Dangers and Stokes seem quite easily bored by straightforward tropes, which ensures that even the more vanilla pieces have a more fluid and ambitious approach to bass lines, chords, and beats than most of their contemporaries.Of the two sister releases, I suppose I prefer the darker, more focused vision of Impossible Star to the more scattered and fun Opaque Couché, but the highlights and endearing curveballs of Couché add up to a similarly impressive achievement.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

In its ongoing series of artist-curated compilations, the Idle Chatter label asked interdisciplinary New York-based artist Muyassar Kurdi to compile its latest release. Specifically presenting female artists from around the world, Reality Tunnels not only further demonstrates the vast expanse of what can be defined as experimental music, but also gives some largely (and unjustly) unrecognized artists a platform to be heard.

In its ongoing series of artist-curated compilations, the Idle Chatter label asked interdisciplinary New York-based artist Muyassar Kurdi to compile its latest release. Specifically presenting female artists from around the world, Reality Tunnels not only further demonstrates the vast expanse of what can be defined as experimental music, but also gives some largely (and unjustly) unrecognized artists a platform to be heard.

The 11 artists that Kurdi selected to participate in Reality Tunnels represent a wide array of styles, from introspective and pensive to pummeling and aggressive.For example, Meira Asher (with Amir Bolzman and Eran Sachs)'s "L'abolition de la Croix" opens up with a distorted noise burst and then punctuates field recordings with additional dissonance, later featuring additional bits of sputtering airplane engines and overdriven explosions. Sukitoa o Namau give a raw edge to 's "Good Boy" via mangled lo-fi stuttering voice samples, distorted fragments of sound, and erratic drum machine rhythms with a unique accompaniment of dog commands and barking.

"Half of Lady Suit," by Lucie Vitkov√°, is not quite as dense, but the erratic drums, horns, and grinding bowed strings have a heaviness all their own.There is a significant amount of abstraction in Anastasia Clarke's "Crushed Matrices #2," but even with all of the scraping, clattering, and vibrations, the piece never veers too far into utter chaos.Diana Policarpo's "Water Gong" is similar with its creaking textures, but has the added dimension of a slightly rhythmic structure to set it apart.

Other contributions here are a bit lighter and overall more tonal in nature.For example, there is some crunch to Elie Gregory's "Train Radio," but on the whole it is a gorgeous piece of electronic abstraction, with wide-open spaces occasionally occupied by layers of electronics and other treated sounds.Similarly, spacy synth layers and lush electronic tones nicely balance the ragged samples of Sharon Gal's "Alarm Call."There is a light and floaty feeling to the twilight field recordings of Yasuno Miyauchi's "Breath Strati" as well that give it a peaceful feel, but never a bland one.

The tape is bookended by two largely vocal-centric performances as well.The opening "Wurzel Arie" by Esmerelda Conde Ruiz consists largely of just her voice, but with the layering, reverb, and other slight effects added, becomes a richer recording of significant depth and complexity.At the other end of the cassette is Kurdi herself, with Ka Baird, presenting "Night Falls, Day Breaks."Essentially a duet between vocals and piano, the combination of Kurdi's unconventional vocal approach and Baird’s pounding performance comes together much differently than the description would imply, and it is all the stronger because of that fact.

Besides the fact that the 11 compositions on Reality Tunnels are so widely varied in their style and approach, the artists Muyassar Kurdi invited illustrates how still gendered and imbalanced the world of experimental music can be.As someone with more than a passing familiarity with the genre, even I did not recognize many of the artists who are presented here.Visiting Bandcamp, I was able to find many of them and significantly more of their works presented.Kudos to Idle Chatter though for doing the work of getting exposure for these deserving artists that have been criminally underexposed thus far.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Sarah and Ariel blend their strong individual personalities in a single trip on the edge of time. Their kosmiche music is pure, magnificent and elegant, an intergalactic hypnosis that seems to tell of distant times, a millenary vortex of a lost Era. In the first phase of departure, the mysterious song of the sax winds in archaic echoes, supported by the electronic inlays of the synth (Arp Odissey). Flowing between space rumbles and astral progressions, we sight high celestial bodies. When the infinite drones of the tampura start, we take part in the night ceremonial, surrounded by the deep harmonium and the Tibetan bell chimes. This music releases a sort of mythological warmth, secret codes of a lost purity, which lets us dwell in the labyrinths of a pyramid or in the sacred space of a cosmic pagoda.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Following a limited vinyl edition in 2018, Oliver Coates’ arrangement of Pulitzer Prize-winning US composer John Luther Adams' 2007 piece Canticles of the Sky appears for the first time across all formats.

In March 2017, Coates conducted 32 cellists in the UK premiere of the composition, displaying its intimacies after deeply communing with the trajectories of Adams' fictional suns and moons, the guiding characters and carriers of the piece.

This recorded interpretation, performed by Coates for multi-layered solo cello, takes Canticles of the Sky to wondrous, dizzying new heights, envisaging Adams' parallel dimension as an idealized construction. Marrying extra-musical studio techniques and meticulous arrangements to Coates' fascination with early electronic synthesis (especially the work of Laurie Spiegel), the result offers an ultra-sensory take on classical string instrumentation.

Coates has released a handful of solo records under his own name, including the acclaimed 2016 album Upstepping, 2017’s Remain Calm, a collaboration with Mica Levi, and most recently, 2018’s Shelley’s On Zenn-La, his debut album for RVNG. As an artist and performer, he is frequently commissioned by world-renowned orchestras, choreographers and visual artists to compose or curate integral new works.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Over the last few years, House of Mythology has become a vacation home of sorts for David Tibet, as he keeps returning there for one unique and ambitious side project after another. This latest divergence finds him teaming up with Andrew Liles for a very quixotic undertaking indeed: an album sung entirely in a dead language (Akkadian, one of Tibet's many deep interests). Given that, I had no doubt at all that it would be one the year’s strangest and unapologetically indulgent releases, but I was still unprepared for how truly bizarre it ultimately turned out to be. Suffice to say, there is nothing else out there quite like Wooden Child, as it feels like an especially unhinged prog opus that took a darkly phantasmagoric turn leading far from any recognizably earthly territory.

Over the last few years, House of Mythology has become a vacation home of sorts for David Tibet, as he keeps returning there for one unique and ambitious side project after another. This latest divergence finds him teaming up with Andrew Liles for a very quixotic undertaking indeed: an album sung entirely in a dead language (Akkadian, one of Tibet's many deep interests). Given that, I had no doubt at all that it would be one the year’s strangest and unapologetically indulgent releases, but I was still unprepared for how truly bizarre it ultimately turned out to be. Suffice to say, there is nothing else out there quite like Wooden Child, as it feels like an especially unhinged prog opus that took a darkly phantasmagoric turn leading far from any recognizably earthly territory.

Both Andrew Liles and David Tibet have had long and colorful histories in underground music's dark fringes and collaborated many times before through Current 93, but this project marks a violent break with both reality and my own expectations that seems to have come from nowhere (or at least from an entirely different dimension than ours).Given Tibet's regular characterizations of his past work as a series of "channelings," it is perhaps possible that the band's enigmatic and imaginary third member The UnderAge Shaitan-Boy played a very large role in this album's direction.Just about anything is possible with this otherworldly and eccentric union.More likely, however, the pair just took the more deranged and hallucinatory edges of Liles' work and used that as a mere jumping off point for a deep plunge into the infernal, lunatic abyss that lies even further out.Perversely, however, Liles and Tibet make a point of stating that "pop" is one of their primary inspirations for this project (along with stars and cuneiform, of course), which is a riddle that I am doomed never to fully unravel.Given that there is plenty of colorful and imaginative misinformation lurking elsewhere in the album's description, it is possible that the duo made that statement purely in jest.Yet it actually seems weirdly sincere despite ample suggestion to the contrary.In a broad sense, there truly are unlikely "pop" elements pervading this entire album, as every song is built on tightly structured synth arpeggios.However, those elements are so abused and transformed by mind-warping effects, pitch shifts, and Tibet’s heavily processed and demonic vocals that "pop" is among the furthest terms from my mind as I subject myself to Nodding God's relentless and candy-colored sensory overload.The finished project feels "pop" only in the sense that it is akin to being terrorized by a malevolent jack-in-the-box.

Attempting to differentiate the individual songs on Wooden Child is mostly a fool’s errand, so the opening "Trapezoid Haunting" essentially lays out the template for the entire album: a warped and demonic-sounding voice intones unrecognizable words in an unfamiliar language over a tensely bubbling synth pattern.Occasionally, Tibet's actual, unprocessed voice will sneak in for a short phrase, or a brief crescendo of disorienting effects will erupt, but the overall effect is a distinctly inhuman one that feels like an unholy and vaguely futuristic Möbius strip. It would be similarly apt to liken the album to an evil fun house or a darkly lysergic maze though, as each piece is just enough like every other piece to make me feel like I am trapped in a nightmarish loop, but just different enough to make it seem like the ground is constantly shifting underneath me.While an especially cool or striking motif fleetingly appears from time to time, it never sticks around long enough to make any one piece feel distinctive or unique.Rather, it feels like I am experiencing an eternal recurrence that grows steadily more hallucinatory and unnerving as I hope for any escape or solid ground in vain.There is no respite to be found.Ever.Given Tibet's exacting approach to Current 93, that insistently escalating sense of visceral discomfort and disorientation has to be intentional, but it is quite a curious path to choose.I suspect there is no one else that would consider "what would a classic Tangerine Dream album sound like if I was drowning in a lake of fire?" a viable or desirable aesthetic.Nevertheless, Liles and Tibet nail that target with remarkable accuracy and force again and again on Wooden Child.

Amusingly, I had to turn off this album while I was writing this review as it is such a relentless and unhinged assault that it became absolutely impossible to think clearly.As such, Wooden Child is a damn hard album to love, though it is also a powerful and unique artistic statement.In fact, it feels like a grotesque inversion of Current 93: all of Tibet's characteristic humanity and poetry has been pointedly erased, as have any vestiges of traditional music's simple, melodic beauty.Instead, Nodding God unleash an abstract miasma of merciless electronic patterns mingled with the twisted voices of the damned.I am tempted to call Wooden Child "the sound of the void" because it feels that way when compared to Current 93, but it would be far more accurate to describe it as immense, harrowing, and overwhelming rather than as an emptiness.In that regard, perhaps the stars truly are one of Nodding God's biggest influences, as this album is akin to a psychedelic supernova that is burning too bright and unfolding too fast to be controlled or sustainable.That unbroken intensity ensures that Wooden Child is unquestionably the most difficult and outré of any of Tibet's recent endeavors, but it is also one hell of a memorable release that does not resemble anything else in his (or anyone else's) discography.

A preview of the album can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Eight years ago, Tim Hecker released his landmark Ravedeath, 1972 album and followed it with an EP that revisited the source material in a more organic, stripped-down fashion (Dropped Pianos). With Anoyo, Hecker beautifully revisits that same trick, albeit this time unveiling Konoyo's underlying gagaku ensemble rather than Ravedeath's underlying pianos. The other significant difference is that Anoyo is more than a mere companion piece that pulls back the curtain to reveal the scaffolding of a great album. Rather, Anoyo arguably equals and completes its predecessor, transforming Konoyo's blackened textures and haunted moods into something significantly warmer, more spacious, and more natural-sounding. Moreover, Anoyo gamely stretches even further from Hecker's comfort zone than its parent. Whereas Konoyo essentially fed Hecker's gagaku guests into a woodchipper, this release feels like a thoughtful, meditative, and organic collaboration with them, as Hecker's electronics eerily drift and swirl through the traditional Japanese sounds like a supernatural mist.

Eight years ago, Tim Hecker released his landmark Ravedeath, 1972 album and followed it with an EP that revisited the source material in a more organic, stripped-down fashion (Dropped Pianos). With Anoyo, Hecker beautifully revisits that same trick, albeit this time unveiling Konoyo's underlying gagaku ensemble rather than Ravedeath's underlying pianos. The other significant difference is that Anoyo is more than a mere companion piece that pulls back the curtain to reveal the scaffolding of a great album. Rather, Anoyo arguably equals and completes its predecessor, transforming Konoyo's blackened textures and haunted moods into something significantly warmer, more spacious, and more natural-sounding. Moreover, Anoyo gamely stretches even further from Hecker's comfort zone than its parent. Whereas Konoyo essentially fed Hecker's gagaku guests into a woodchipper, this release feels like a thoughtful, meditative, and organic collaboration with them, as Hecker's electronics eerily drift and swirl through the traditional Japanese sounds like a supernatural mist.

From the opening sweep of koto notes that leads into "That World," it is immediately apparent that Anoyo presents a side of Tim Hecker quite unlike any that I have seen before.If I did not know better, I would guess that he offered to record and produce the gagaku musicians' own album in exchange for their work on Konoyo, as the most predominant sounds are dreamily snaking and billowing masses of flutes rather than anything that sounds conspicuously Hecker-esque.Obviously, that is not the case, yet Hecker treats the source material with an uncharacteristic delicacy and lightness of touch on that particular piece, overtly showing his hand only through the deep bass tones and the fluttering swells of backwards strings.The flutes are the true heart of "That World," however, and they attain an almost "chills down the spine" level of ghostly beauty.Consequently, Hecker wisely leaves the piece as spacious and uncluttered as possible, as adding anything further would have only diluted the magic.The following "Is But A Simulated Blur," on the other hand, heads in the opposite direction, as the warped and woozy synth-like drones are very much textbook Hecker.He ingeniously twists the formula in quite a striking way though, as a haze of feedback or processed flutes swoops and plunges eerily in the periphery while pounding, erratically timed taiko and kakko drums imbue the piece with a very meditative and ritualistic feel.The first half of the album then winds to a close with the sublime and vaporously undulating drones of "Step Away From Konoyo."

Anoyo's second half initially picks up right where the first half left off, as "Into the Void" is yet another understated drone piece, though its gently tumbling, fragmented strings and uneasy dissonances give it a darkly impressionist feel rather than a meditative one.When contrasted with the surrounding pieces, "Step Away" and "Into the Void" can seem like a mid-album lull of sorts, but it is a deliberate one: Anoyo's arc can be viewed as a steady constriction followed by a similarly steady expansion back to its original state.Or, more abstractly, like a deep exhalation followed by a deep inhalation.

Correspondingly, the album starts to reassemble into more ambitious and structured forms with "Not Alone."Much like with "Simulated Blur," the shifting tempos of the drumming give the piece an exotic and ritualistic air, but Hecker is even more restrained this time around and limits his palette to just quivering washes of slow chords.It is an airy and quietly lovely piece.In keeping with the album’s telescoping trajectory though, it is the closing "You Never Were" that makes the deepest impact of Anoyo's resurgent second half.Initially, the backbone of the piece is a fitful, broken-sounding koto motif adrift in a quavering sea of shimmering feedback or harmonic swells.Gradually, however, a submerged organ theme starts to emerge from the haze, and a different snatch of melody appears that unpredictably sputters and sizzles in the foreground.In the final moments it fully blossoms into a blurred and dreamlike organ mass, but the real beauty of the piece lies in how elegantly Hecker manipulates textures and dynamics as he moves towards that destination.

For about a week, I was absolutely convinced that Anoyo was a better album than Konoyo, but I eventually realized that I was just completely in love with "That World" and had a deep fondness for taiko drumming."That World" is one of Hecker's career-defining masterpieces, and a few other songs beautifully evoke a mystical, dream-like ritual, which is more than enough to make Anoyo ("that world") a significant release.However, focusing on the individual songs neglects the deeper and more thoughtful artistry of the whole.Taken as a stand-alone work, these songs flow together seamlessly in a satisfying arc, achieving an exquisite symmetry.I was also struck by how the song titles form a hopeful non-traditional haiku.However, Anoyo is not a stand-alone work–it is the yang to its predecessor's yin (or vice versa).The song titles of Konoyo ("the world over here"), for example, also form a poem (a considerably darker one).While the overarching concept uniting the two halves is ambiguous enough to interpret in various ways (particularly since I have seen differing translations of "konoyo"),that ambiguity does not detract from their power and beauty as a diptych.In fact, that open-endedness even enhances those traits, as it is possible to project any number of themes (religious and otherwise) in the transformation from Konoyo's bleak torment to Anoyo's clarity and transcendence.Hecker essentially mirrors the anxiety, darkness, and pain of the modern world, then pulls back the camera to show that the sorrow and chaos are mere details of a rich and complex tapestry (or possibly that it is all an ephemeral illusion).Either way, The Transfiguration of Timothy Hecker is a moving and absorbing event.With the exception of perhaps Virgins, Anoyo and Konoyo go the furthest of Hecker’s albums in eroding his usual artistic distance to reveal depth and feeling in a raw and direct way.

Samples can be found here.

Read More