- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

The latest ambitious durational epic from the Opalio brothers is thankfully not nearly as daunting as its 15-disc physical form suggests, as RINASCIMENTO ("Renaissance") is composed of 15 movements of varying lengths ranging from 5 to 40 minutes. The reasoning behind the unusual format is arguably twofold, as the Opalios' belief that "each sound claims its own space" is extended to dedicate a full disc to each movement and listeners are invited to "subvert the order" to make use of "random/chance operation à la Cage." There is an additional piece to the puzzle as well, however, as the handcrafted box and CD-R format were deliberately chosen as a return to MCIAA's "radical DIY" origins and as a pointed commentary on underground music's current maddening dependence on vinyl pressing plants and predatory corporations. Unsurprisingly, the primary appeal of RINASCIMENTO is the same as that of every other multi-hour MCIAA tour de force: it is a sustained and mind-altering plunge into otherworldly psychedelia that abandons nearly all earthbound notions of harmony, melody, structure, and instrumentation (and that is not an exaggeration). While the brothers' sonic palette will be a familiar one for longtime MCIAA fans (being a two-person real-time "spontaneous composition" project has some limitations), RINASCIMENTO is nevertheless one hell of a statement, as it collects the duo's most revelatory flashes of inspiration from an entire year of recordings (several of which capture the duo in peak longform form).

The latest ambitious durational epic from the Opalio brothers is thankfully not nearly as daunting as its 15-disc physical form suggests, as RINASCIMENTO ("Renaissance") is composed of 15 movements of varying lengths ranging from 5 to 40 minutes. The reasoning behind the unusual format is arguably twofold, as the Opalios' belief that "each sound claims its own space" is extended to dedicate a full disc to each movement and listeners are invited to "subvert the order" to make use of "random/chance operation à la Cage." There is an additional piece to the puzzle as well, however, as the handcrafted box and CD-R format were deliberately chosen as a return to MCIAA's "radical DIY" origins and as a pointed commentary on underground music's current maddening dependence on vinyl pressing plants and predatory corporations. Unsurprisingly, the primary appeal of RINASCIMENTO is the same as that of every other multi-hour MCIAA tour de force: it is a sustained and mind-altering plunge into otherworldly psychedelia that abandons nearly all earthbound notions of harmony, melody, structure, and instrumentation (and that is not an exaggeration). While the brothers' sonic palette will be a familiar one for longtime MCIAA fans (being a two-person real-time "spontaneous composition" project has some limitations), RINASCIMENTO is nevertheless one hell of a statement, as it collects the duo's most revelatory flashes of inspiration from an entire year of recordings (several of which capture the duo in peak longform form).

The first movement of this 5 ½ hour epic is a deceptively brief and harsh one, as a miasma of tape hiss, whines, and jangling metal sounds call to mind someone slowly dragging a mass of metal cans ("just married!") around a burst pipe in a queasy swirl of alien harmonies and gibbering electronics. In theory, the fifteenth and final movement (smoldering feedback slowly streaking over thumping ritualistic percussion amidst a fog of cooing voices) is not radically different from that opening piece, but it certainly FEELS very different when it eventually comes because it is impossible to listen to 5+ hours of MCIAA without feeling like one's mind has been fundamentally transformed in some way by the sustained plunge into the Opalio's smeared, unnerving, and otherworldly vision. That said, some of the longer movements can achieve a similar effect in drastically reduced time on their own.

Given the fact that the Opalios are playing everything in real time spontaneously, the strongest movements feel akin to witnessing a solar eclipse: it takes a while for all of the moving parts to lock into the right places, but the spectacle can be quite transcendent once the threshold is finally reached. To my ears, RINASCIMENTO starts to truly catch fire around the fourth movement ("Revenge Of Native Aliens") and reaches its zenith somewhere between the eighth and tenth movements, but there are plenty of wild deep space mindfucks on either side of that stretch. For example, the second movement fleetingly calls to mind a flock of honking psychedelic birds disrupting a holodeck beach trip, while the fourth movement evokes the feeling of slowly sinking in a space bog while being serenaded by a lysergic chorus of extradimensional frogs and crickets.

That fourth movement kicks off a sustained and increasingly inspired run of highlights, but the top-tier consciousness-expanding mindbombs are movements six, eight, nine, and ten. In "Fury Of The Alien Gods," for example, it sounds like a free jazz drummer is consumed by a time-bending supernatural haze while jamming with an interplanetary distress signal.

Elsewhere, "Aliencentricism" passes through stages evoking everything from "flock of birds enveloping an extraterrestrial kinetic metal sculpture" to "a field of rusted metal wires vibrates in the wind while an insistent distress signal endlessly reverberates around the ruins of an abandoned space colony." "Matter Becomes Spirit," on the other hand, approximates some kind of slow-motion industrial dub, as a series of erratically timed metal clanks shudders and echoes beneath a smoldering alien melody of smeared beeps that sounds like the death song of a burning space station. "Alienophony" also evokes a looping distress signal in an abandoned place, but as a connoisseur of the genre, I can confidently report that it has an entirely different character this time around ("squirming and squelching short wave radio transmissions in blizzard-ravaged arctic outpost").

The descent back to earth from those peaks is a gradual one, however, as the journey has a few more memorable stops before the final station (for example, "The New Verb" sounds like a doomed astronaut trying to navigate through a supernatural windstorm with unreliably bending and warping sonar pings). While the wealth of highlights here is admittedly quite a treat, it is worth noting that MCIAA is one of the rare projects in which the varying appeal of individual compositions is distantly secondary to the overall vision, as one does not need to get very deep into RINASCIMENTO (or just about any other MCIAA albums) to reach one of two conclusions. One of those conclusions is probably "I need to turn this off because this nerve-jangling, unearthly cacophony is burrowing into my mind and rapidly driving me insane," but the other one is "this unearthly cacophony is burrowing into my mind like absolutely nothing else that I have ever heard and I love it." For those that fall into the latter camp, a fresh durational monster from the Opalios is a legitimate event and the fact that there are several highlight reel-level pieces here is just further delicious icing on an already wonderful and unique cake. The Opalios are not wrong in their claim that RINASCIMENTO is future music happening in the present, as their complete rejection of contemporary music's established framework unquestionably represents at least ONE possible future. Whether or not it represents THE future remains to be seen, yet landmark MCIAA releases like this one are objectively as forward-thinking as many previous innovations that have provocatively challenged the way that people understand, experience, and appreciate organized sound (such as Just Intonation, chromaticism, John Cage's use of the I Ching, or the birth of noise).

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This is the second solo album from NYC-based violist/composer/musicologist Annie Garlid and it borrows its name from the Greek word for "place." Notably, Garlid moved back to the US in 2018 after spending a decade in Europe (playing viola in a German opera orchestra, among other things) and that return to her home country unsurprisingly stirred up some deep and unfamiliar thoughts and feelings. Those ruminations directly inspired Topos conceptually, as the album is a meditation on the "simultaneous familiarity and foreignness" of Garlid's surroundings and her entanglement "with a place that was both in her memory and in front of her eyes." Regardless of its inspirations, Topos is a very different (and stronger) album than its predecessor United, as Garlid's medieval and baroque influences are newly downplayed in favor of a more sensuous, hallucinatory, and vocal-centric vision. While that transformation makes a lot of sense given Garlid's work with artists like Caterina Barbieri, Holly Herndon, Emptyset, and ASMR artist Claire Tolan, her assimilation of those disparate influences is impressively seamless and inventive, as Topos feels like the blossoming of a compelling and distinctive new vision.

This is the second solo album from NYC-based violist/composer/musicologist Annie Garlid and it borrows its name from the Greek word for "place." Notably, Garlid moved back to the US in 2018 after spending a decade in Europe (playing viola in a German opera orchestra, among other things) and that return to her home country unsurprisingly stirred up some deep and unfamiliar thoughts and feelings. Those ruminations directly inspired Topos conceptually, as the album is a meditation on the "simultaneous familiarity and foreignness" of Garlid's surroundings and her entanglement "with a place that was both in her memory and in front of her eyes." Regardless of its inspirations, Topos is a very different (and stronger) album than its predecessor United, as Garlid's medieval and baroque influences are newly downplayed in favor of a more sensuous, hallucinatory, and vocal-centric vision. While that transformation makes a lot of sense given Garlid's work with artists like Caterina Barbieri, Holly Herndon, Emptyset, and ASMR artist Claire Tolan, her assimilation of those disparate influences is impressively seamless and inventive, as Topos feels like the blossoming of a compelling and distinctive new vision.

The five pieces that compose Topos cover an unexpectedly expansive stylistic territory, as each individual piece takes a very different path than the other four. For example, the opening "Riverbeds" is not a far cry from Laura Cannell's sublime art-folk, as string drones sensuously rub up against one another beneath hushed, spoken vocals. It is a fine piece, but the two that follow are the ones where Garlid's vision truly catches fire.

On "March 6th" she conjures up a psychotropic folk dance by combining a viscerally stomping and clapping rhythm with a serpentine pizzicato string motif, Siren-esque choral stabs, and vocals that resemble an eerily harmonized jump rope game. On the following "Ocelot," Garlid's hushed voice ruminates on her favorite childhood animal ("you were the jewel of the catsssss") over a gorgeously sensuous groove enhanced with dreamy vocal harmonies. It is sexy, simmering, and psychedelic in all the right ways, but I was most struck by the seemingly effortless virtuosity of Garlid's vocal phrasing, as she artfully veers between trance-like spoken word, warmly harmonized choral melodies, creepily unsettling effects, pregnant pauses, and hissing sibilance.

The album's final piece, "Forest Floor," is yet another gem, as Garlid enlists a handful of collaborators (her sister Thea, flautist Rebecca Lane, saxophonist Eve Essex) to craft a wonderfully shapeshifting ambient fantasia of whispers, field recordings, hazy snaking melodies, and subtly trippy chorused guitar fragments. Given its more vaporous and elusive form, it does not quite match the impact of the album's stellar first half, but it makes for quite a lovely way to end an album, as the closing minutes evoke a ghostly folk ensemble slowly dissolving in a thunderstorm. The album's remaining piece ("Robert") is not quite up to the same standards, acting more as an interlude than a fully formed statement, but that does not otherwise dilute Topos' impressive run of highlights or dampen my view that this album is a huge creative leap forward for UCC Harlo. That said, "March 6th" and "Ocelot" are on a separate and revelatory plane all their own, as they easily rank among my favorite new pieces in recent memory and resemble no other artist that I am aware of.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

Just about anything which bucks stereotypes, and the more effortlessly the better, is usually fine and dandy with me. The notion of a sustained outbreak of surrealism down in Alabama is therefore beyond delicious. I say this because there's a definite sense in which Turner Williams Jr. is following in the rambling loose limbed footsteps of such musicians as Ron Pate, Fred Lane, LaDonna Smith, and particularly Davey Williams, who studied with Johnny Shines and was part of the whole Raudelunas Pataphysical Revue scene - playing alto and guitar on such pieces as "The Lonely Astronaut" and "Concerto For Active Frogs''. Let me say here that the origin of pataphysics is perhaps best left to another time, since Alfred Jarry's absurdity and all that merde (absinthe-fueled and otherwise) simply cannot be skimmed over.

Just about anything which bucks stereotypes, and the more effortlessly the better, is usually fine and dandy with me. The notion of a sustained outbreak of surrealism down in Alabama is therefore beyond delicious. I say this because there's a definite sense in which Turner Williams Jr. is following in the rambling loose limbed footsteps of such musicians as Ron Pate, Fred Lane, LaDonna Smith, and particularly Davey Williams, who studied with Johnny Shines and was part of the whole Raudelunas Pataphysical Revue scene - playing alto and guitar on such pieces as "The Lonely Astronaut" and "Concerto For Active Frogs''. Let me say here that the origin of pataphysics is perhaps best left to another time, since Alfred Jarry's absurdity and all that merde (absinthe-fueled and otherwise) simply cannot be skimmed over.

On the three tracks here, at least, Williams Jr. manages to play a variety of strings with a truly wild yet intensely focused style. I have not heard much like it. In a humdrum world of scissor kicking guitarists he's a real Fosbury Flop. The resulting waves of jangled and strangled sounds at times resemble a bottleneck jam of notes being squeezed and released; like traffic buzzing along, slowing, and then oozing through a toll gate to speed along or crash and explode. Eastern-tinged vibrations dominate throughout, as if electricity were throbbing along desert telegraph wires, setting fire to antique receiving equipment in some remote Embassy with a boom, crackle and pop, and dispatching fierce hums and whines of distorted feedback, throbbing backwards and squealing up through hot air rising and howling like out-of-control robot space-wolves bouncing off an old knackered rusted satellite on their way to oblivion. Or maybe to Oblivion, Alabama.

To stunning effect, he plays electric shahi baajas, (probably) bulbulturang, definitely FX and Gaz, and some other instruments which I haven't yet deduced. He plucks and thrashes as skillfully as someone with a PhD in plucking and medals for thrashing, who recently woke up and decided to quit messing around and work at really cranking up his game. That is not an indictment of his previous releases, by the way, because I haven't yet found time to hear any of them. Briars On A Dewdrop can easily be digested in one sitting or sampled track by track in any order. The lengthy third piece "On A Dewdrop" has a scorching crescendo which left me wanting more, so I'd have preferred for that final track to precede the more spacious "Briars." Actually I'd also like for the pieces to swap titles as well, because "On A Dewdrop" is much more spiky and prickly. I suppose it is more surreal to have the titles mixed up, though, but then again I'm Dada all the way so I am leaving that to the surrealists.

Williams Jr. has fairly recently decamped to France, and he recorded these pieces before heading off. These are beautifully tangled stylistic brambles through which to wade, a marvelous journey which in theory could be spent trying to work out how it all fits together, but that isn't really necessary, and neither is a thick tweed jacket or thornproof headphones. The flow is the thing, and like a river hitting a weir before cascading down over rapids, this music has it in spades. What comes to mind is hard to describe: part Dogon spacecraft with a wheel in the ditch, part absurd Ubu Roi theatrics, part three million bicycles carried by the fleeing shirtless population of a flooded Asia, part chubby cow jumping over the doggone moon.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

This is the fifth album of traditional folk tunes which Alasdair Roberts has issued. He has also released several albums of his own compositions and it is a mark of his skill that it is pretty much impossible to tell the difference, and to know whether songs are his own imaginings or not. All share an erudite sensibility, often mixing his plaintive ghostly wailing voice (sometimes mournful, often joyous) with fine, spidery, guitar accompaniment. This new record is a deep collection, full of sweet spots, rich in detail, crystal clear in execution, and teeming with life. As usual, he reveals the multilayered meanings and nuances in even the most apparently straightforward songs, as with "The Bonny Moorhen" of Celtic folklore, and "Drimindown," a simple tale of a lost cow but also a devastating loss of a family's livelihood.

This is the fifth album of traditional folk tunes which Alasdair Roberts has issued. He has also released several albums of his own compositions and it is a mark of his skill that it is pretty much impossible to tell the difference, and to know whether songs are his own imaginings or not. All share an erudite sensibility, often mixing his plaintive ghostly wailing voice (sometimes mournful, often joyous) with fine, spidery, guitar accompaniment. This new record is a deep collection, full of sweet spots, rich in detail, crystal clear in execution, and teeming with life. As usual, he reveals the multilayered meanings and nuances in even the most apparently straightforward songs, as with "The Bonny Moorhen" of Celtic folklore, and "Drimindown," a simple tale of a lost cow but also a devastating loss of a family's livelihood.

I probably first heard and liked the music of Alasdair Roberts in August 1997 when on an English summer holiday at Woodspring Priory—or Worspring as it was known in the Middle Ages. It was founded in 1210 by William de Courtenay, grandson of Reginald Fitz-Urse, one of the assassins of St Thomas Becket. Providing an income for the locals was likely a way for de Courtenay to purge his family's ongoing guilt, and indeed St Thomas is patron saint of the priory and his martyrdom depicted on its seal.

Woodspring was continuously improved right up until 1536 when it was suppressed and bashed about by Henry VIII—probably because no one believed he'd go through with his wrecking plans. Today Woodspring is remarkable for the way in which it was converted after the Dissolution: the new Tudor owners putting their house right inside the church itself! Now, imagine all this as a beguiling airy narrative seasoned with blood, ghosts, tears, and romance, and you'll start to get an idea of the kind of detail and atmosphere in the recordings of Alasdair Roberts.

The tune I heard back then was "Well Lit Tonight" from his earliest group called Appendix Out. Most likely I had recorded the John Peel radio program and was taking a short break from beer, whisky, sausages, cake, cricket, and the board game Fair Means Or Foul to re-listen to the show on a cassette recorder and pick out what I thought were the gems. Since that time, Roberts has released a torrent of music and also engaged with a rare enthusiasm in myriad collaborations. In a sense, though, nothing has changed: the uncluttered nature of his tunes invariably allows them to shine like stars against a clear dark winter night. Incidentally, the way he collaborates is also admirable: never hogging the limelight but never basking in reflected glory either. What is new on Grief in the Kitchen and Mirth in the Hall is piano accompaniment on several tracks. Naturally this works because it sounds completely unforced and, well, natural—not least with Roberts swapping gender to sing "The Lichtbob's Lassie."

The album title is a strong clue to his delicate yet microscopically all-encompassing approach, subtly exploring the extremes of human experience and much that is in-between; as down to earth as a mud clad chapter of John Berger's writing in Pig Earth and as stunningly phantasmagorical as the final piece here "The Holland Handkerchief." If Philip K Dick had written folk ballads rather than novels, even he might have struggled to come up with such a tale.

When Alasdair Roberts exits this earthly realm, hopefully a long time from now, I am certain that his passing will trigger a deeply reverential critical assessment of the amazing body of recorded work he will leave behind; whether self-penned songs or works unearthed from the traditional seam.

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest album from Markus Popp marks yet another intriguing stylistic detour for his endlessly shapeshifting Oval project, as he delves into "an omnipresent and yet oft ill-defined, even maligned area of music and art–the romantic." The idea for this album first began as a multimedia collaboration with digital artist Robert Seidel intended for the grand opening of Frankfurt's German Romantic Museum, but the endeavor soon evolved and expanded beyond the original purpose, as the two artists "sought a more expansive definition of 'romantic,' extending outward from the museum's comprehensive survey of the 19th-century epoch in art." That said, I suspect only Popp knows how influences from literature, architecture, and visual art helped shape the album, as my ears can only process the final destination and not the journey. In the case of Romantiq, that destination feels like a series of brief vignettes/miniatures assembled from period instrumentation and filtered through Popp's fragmented and idiosyncratic vision. Given that this is an Oval album, of course, very few of the 19th-century sounds are instantly recognizable as such (aside from some occasional piano), but Popp's kaleidoscopic and deconstructed homage to the past is a characteristically compelling and intriguingly unique outlier in the Oval canon (and it is often a textural marvel as well).

This latest album from Markus Popp marks yet another intriguing stylistic detour for his endlessly shapeshifting Oval project, as he delves into "an omnipresent and yet oft ill-defined, even maligned area of music and art–the romantic." The idea for this album first began as a multimedia collaboration with digital artist Robert Seidel intended for the grand opening of Frankfurt's German Romantic Museum, but the endeavor soon evolved and expanded beyond the original purpose, as the two artists "sought a more expansive definition of 'romantic,' extending outward from the museum's comprehensive survey of the 19th-century epoch in art." That said, I suspect only Popp knows how influences from literature, architecture, and visual art helped shape the album, as my ears can only process the final destination and not the journey. In the case of Romantiq, that destination feels like a series of brief vignettes/miniatures assembled from period instrumentation and filtered through Popp's fragmented and idiosyncratic vision. Given that this is an Oval album, of course, very few of the 19th-century sounds are instantly recognizable as such (aside from some occasional piano), but Popp's kaleidoscopic and deconstructed homage to the past is a characteristically compelling and intriguingly unique outlier in the Oval canon (and it is often a textural marvel as well).

The album's description promises a perfume-like experience ("rich scents flooding the senses before evaporating on the breeze"), which feels weirdly apt, as most of the pieces feel like a fleeting impression of something beautiful rather than an intentionally substantial experience (though the album itself is a substantial whole). That approach makes sense given the album's origins as just one part of a larger installation, yet these pieces do not feel like they are missing anything—they simply feel purposely ephemeral, elusive, and impressionistic. In more concrete terms, many of the pieces sound like a music box made of crystal that has been modified to make its simple melodies unpredictably stammer, smear, and flicker. While that is an admittedly cool baseline aesthetic, the stronger pieces on the album tend to be the ones that enhance that foundation with some kind of inspired addition. For example, the opening "Zauberwort" features both a trombone and a recording of an opera singer unrecognizably "atomized into smoke trails."

To my ears, the album's centerpiece is the wonderfully phantasmagoric "Okno," which feels like a smeared and convulsive orchestral loop dueting with a glass vibraphone, but that description fails to do it justice (it more accurately lies somewhere between "violently remixed film score" and "chopped and screwed rendition of 'Dance of the Sugarplum Fairy'"). The following "Touha" is quite wonderful as well though, as it approximates a crystalline and psych-damaged variation on Aphex Twin's Drukqs-era computer-controlled piano pieces. Elsewhere, "Cresta" and "Amethyst" combine for another strong one-two punch, as Popp beautifully elevates his "crystal music box" vision with psychotropic tendrils and a host of burbling, gurgling, and smeared electronic sounds.

Admittedly, there are also a couple of more traditionally piano-centric pieces that do not quite connect with me, but this is otherwise a solid and playfully anachronistic (if modest) album that reaffirms my Oval fandom yet again. Obviously, some Oval releases make a much deeper impact on me than others, yet the recurring theme in Markus Popp's career continues to be one of bold and continual reinvention. While it has been roughly three decades since he first exploded onto the scene with his groundbreaking "skipping CD" innovations, he continues to focus his formidable production skills on bending and stretching the boundaries of electronic composition and seems to have an almost pathological aversion to ever repeating himself or taking an expected path. While plenty of artists give fans exactly what they want, Popp is one of the rare artists who is far more interested in nudging adventurous listeners towards sounds and ideas that transcend the familiar (like a perfume-esque and partially architecture-inspired fantasia of deconstructed 19th-century romanticism, for example).

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

I am obsessed with circles, but you don't need to share that obsession to notice and appreciate the gesture of respect here from Tujiko Noriko to Peter Rehberg with the insistence that Crepuscule I & II be issued in various formats, including cassette. Many years ago she dropped a cassette tape into the hands of the MEGO and Editions MEGO label founder. The tape contained her first album and, despite it being a big departure from the typically more brash and raw fare he was normally releasing, Rehberg liked what he heard and gave it a proper push. Universal acclaim did not follow.

I am obsessed with circles, but you don't need to share that obsession to notice and appreciate the gesture of respect here from Tujiko Noriko to Peter Rehberg with the insistence that Crepuscule I & II be issued in various formats, including cassette. Many years ago she dropped a cassette tape into the hands of the MEGO and Editions MEGO label founder. The tape contained her first album and, despite it being a big departure from the typically more brash and raw fare he was normally releasing, Rehberg liked what he heard and gave it a proper push. Universal acclaim did not follow.

Just before Peter Rehnerg's death he was apparently digging a pre-release of this new album. The opening track "Prayer" may have gripped him; it certainly floored me, with Tujiko instantly wringing great emotional heft from machine templates. Sadly it is as short as it is sweet. I cannot, and will never, understand why this simple but dazzling piece is issued as a mere 2.22 minute duration, rather than 22 minutes, or even 2 hours 22 minutes. Baffling. The album title refers to twilight, and much of the music is reflective and meditative—without being sluggish or over-sentimental. To paraphrase a philosopher or poet whose name I forget, in terms of our lifespans "everyone imagines that it is late morning, but it actually is midafternoon." Part of the human condition, perhaps. At any rate, Crepuscule seems to be a musing about time passing, about ends, beginnings, and transitions, as much as a reference to the twilight realm as a quality of light, with atmospheres of melancholy or nostalgia, of uncertainty and mystery.

The starting points for much of Tujiko's music are images, either mental pictures or—when called upon to make soundtracks—actual movie visuals. Given this backdrop, and her experience of film music composition, it's no surprise that sections of the album can be described as cinematic. By this I do not mean the limited idea of languid plucks and anguished swells likely to induce thousand yard stares or slow motion glides through one's subconscious for a re-imagining of every trivial incident as if they all have sacred significance for the history of the universe. Of course they all do, but my point is that the ones captured here are not set to glum, ponderous music.

It may be pointless to approach Crepuscule with anything other than a microscopic focus and a monastic patience. I advise imagining yourself as the character in the film Black Narcissus endlessly seeking to look for signs beyond this world. They will surely appear. As a child my wife was mildly rebuked for claiming she could hear the aurora borealis. Now scientists suggest that they have indeed been able to detect sound emitted from the area. Some fine images emerge while listening to this album. "Fossil Words" has a stately pace and an eerie portentous feeling. In my mind it resembles a sunken ship or submarine being brought to the surface very slowly for fear of spilling polluting mercury into the ocean

I enjoyed the hushed intimacy of "Cosmic Ray." Another personal favorite, "A Meeting At The Space Station" is wide open to interpretation. Whatever images come to mind all work, Leonard Rossiter in 2001 or Bruce Dern in Silent Running, perhaps. It's a track cut loose from a film and left to float aimlessly through space in search of a movie: and it gets better the longer you stick with it. "Flutter" is a not so distant cousin of "Prayer" and I'm not judging. Edvard Greig, John Adams, Albert Einstein all married their first cousins; Grieg at least in part for musical reasons. "Bronze Shore" has a weird, vaguely psychotic tone—the kind which may arise when innocent voices are overlain with nicely distorted electronics, as if children counting or reciting a nursery rhyme become figures transformed into a brainwashed state.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest full-length from Lucy Liyou is described as a "rumination on the double-sidedness of trauma and love." The title is a Korean idiom with multiple meanings ("could mean anything from fanciful daydreams to nightmarish terrors") and was chosen very deliberately, as Liyou is fascinated by what our dream lives say about us and our subconscious desires. Interestingly, Dog Dreams is billed as only Liyou's second album (she is quite a prolific artist), but apparently everything other than 2020's Welfare is considered either an EP or a collaboration. In some ways, Dog Dreams feels like a logical evolution from that debut, but I was surprised to find that Liyou moved away from her text-to-speech narratives, as I previously thought that element was absolutely central to her aesthetic. In their place, however, are elusive Robert Ashley-esque dialogues of murmuring voices hovering at the edge of intelligibility. While I expected to miss the playfully dark humor of those robotic voices quite a lot (I found them very endearing), the newly tender and human voices fit the dreamlike beauty of Dog Dreams' three sound collages quite nicely.

This latest full-length from Lucy Liyou is described as a "rumination on the double-sidedness of trauma and love." The title is a Korean idiom with multiple meanings ("could mean anything from fanciful daydreams to nightmarish terrors") and was chosen very deliberately, as Liyou is fascinated by what our dream lives say about us and our subconscious desires. Interestingly, Dog Dreams is billed as only Liyou's second album (she is quite a prolific artist), but apparently everything other than 2020's Welfare is considered either an EP or a collaboration. In some ways, Dog Dreams feels like a logical evolution from that debut, but I was surprised to find that Liyou moved away from her text-to-speech narratives, as I previously thought that element was absolutely central to her aesthetic. In their place, however, are elusive Robert Ashley-esque dialogues of murmuring voices hovering at the edge of intelligibility. While I expected to miss the playfully dark humor of those robotic voices quite a lot (I found them very endearing), the newly tender and human voices fit the dreamlike beauty of Dog Dreams' three sound collages quite nicely.

Unsurprisingly, Dog Dreams has its roots in Liyou's own recurring dreams, but it is also a dialogue of sorts with co-producer Nick Zanca, as the two artists first worked on the album separately before convening in Zanca's studio to shape the final version. The opening title piece provides a fairly representative introduction to the album, as a melange of faint pops, hisses, and crackles slowly blossoms into a pleasantly flickering and psychotropic collage of tender piano melodies, water sounds, and sensuously hushed vocals. Interestingly, the aforementioned melange of strange sounds came from recordings of saliva (albeit "dilated and rendered unfamiliar through Zanca's adroit mixing"), which is definitely not something that I would have guessed on my own. Characteristically, the vocals are the best part of the piece, as Liyou and Zanca's voices enigmatically mingle, overlap, and harmonize in a fractured, shapeshifting dialogue. Uncharacteristically, however, "Dog Dreams" transforms into something resembling Xiu Xiu's Jaime Stewart interpreting a tender R&B-tinged ballad from a Disney soundtrack. While I certainly did not see that curveball coming, it is very on-brand for Liyou, as she has always been an inventive magpie keen to assimilate any and all compelling sounds and ideas that bleed into her life.

The shorter second piece ("April in Paris") is the album's strongest, as Liyou blends together an abstract rendition of a "Vernon Duke jazz standard" with a narrative reflection on sexual assault. Despite the heavy subject matter, it is an absolutely gorgeous piece that feels like a series of evocative dissolving mirages that run the gamut from "sultry jazz fantasia" to "churning nightmare." It may very well be my favorite piece that Liyou has ever recorded, but "Fold The Horse" ends the album with another gem, elegantly blurring the lines between "field recordings from a factory inside a snow globe" and "hypnosis session in the middle of an animated Disney forest full of cheerfully chirping birds." Curiously, It climaxes with yet another R&B-inspired passage, which predictably wrong-footed me yet again. Those "bursting into song" moments tend to feel a bit out of place to me, which is my one caveat with this album, but the unusual seesawing between pop and surreal abstraction makes for compelling art regardless (dreams fundamentally follow their own logic, after all). In any case, this is an absolutely beautiful and unique album, as Liyou and Zanca crafted quite a sensuous, bittersweet, and immersive channeling of Liyou's swirling subconscious. Moreover, there is enough mystery lurking in these diaristic dreamscapes to make me want to revisit them again and again to reveal fresh details and new shades of meaning. To paraphrase one of the album's central samples ("the outer person isn't necessarily always the inner person"), the immediately graspable elements of Dog Dreams are merely an entry point to its fathomless depths.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

Vandever's first solo album was recorded in three days and features her improvising on (mainly) trombone, effects, and voice. The improvised approach never shoves this music even an inch away from clarity, deftness, and emotional depth. Every piece feels fresh, abstract and dreamlike—as if she's channeling spirit voices from elsewhere—but all are restrained by the beguiling warmth, subtle tension, and comforting understatement of her sonorous playing. It's marvelous to hear the trombone burst, or maybe a more accurate descriptor would be slide, free of all genre association.

Vandever's first solo album was recorded in three days and features her improvising on (mainly) trombone, effects, and voice. The improvised approach never shoves this music even an inch away from clarity, deftness, and emotional depth. Every piece feels fresh, abstract and dreamlike—as if she's channeling spirit voices from elsewhere—but all are restrained by the beguiling warmth, subtle tension, and comforting understatement of her sonorous playing. It's marvelous to hear the trombone burst, or maybe a more accurate descriptor would be slide, free of all genre association.

From the opening tune, entitled "Recollections From Shore," the album riffs off echoes and memories from Vandever's childhood in Hawaii, although this knowledge did not stop my imagination from going wherever it wished. During "Stillness In Hand" I was soon picturing steam trains huffing and puffing through a damper, gently undulating, European landscape. Then, while enjoying "Temper the Wound" I began seeing myself flying a box kite high in the sky one 1960s summer day on the East coast of England. That latter piece and also the even slower track "Held In" both give the feeling of having been created by harnessing pain or past scars to produce sounds that balance sadness with strength and survival. I have read of her mentioning waking from dreams in tears, or being comforted by visits from past memories and spirits—some when asleep and others when awake. At any rate, the softness and subtlety of this music lingers in the brain like the sound of hard-earned and humble wisdom. In Vandever's hands the trombone leaves behind any single genre or any other limitation. Effects are not overdone, and technique is hidden in plain sight as simple unhurried phrases loop, fold, or crumble slightly into themselves in a barely decipherable but extremely melodic manner.

A clear sign of a beloved record, and that's how I feel about We Fell In Turn, is when it is immediately satisfying but also slowly reveals more of itself, is deep and substantial enough to bear repeat listens yet always seems to end too soon. Engineer and producer Lee Meadvin is credited for giving valuable prompts, which presumably assisted in focusing and framing these brilliant improvisations. Hearing this was like an open goal for me, hopefully in a good way. I say that because the term "prompts" is now, of course, associated with the use of AI. To clarify: there is nothing even remotely artificial about We Fell In Turn. Furthermore, the luckiest bot program on earth could not have hit this bullseye if asked to imitate "an extremely detailed trombone recording in the style of Robbie Basho's "Orphan's Lament" and William Basinski's The Disintegration Loops along with atmospheric tones and cool yet melancholy textures." Which is not to say that methodology is everything. We read everyday about how artist x has, for instance, only used analogue equipment to create album y (but that can't save it from sounding like a huge confused messy zzzz). No such problem here as Kalia Vandever does not put a foot wrong.

At this point I could refer to such distinctive proponents of an instrument as Jan Garbarek, although Laura Cannell (cello and recorder) and maybe Kali Malone (pipe organ, synthesizer) also come to mind. Similarly, Vandever is taking the time to sincerely communicate the essence or feeling of true tales with a sonorous power, both memorable and restrained. Rather than trying to do too much, overreaching, and muddling things, she proceeds at her own pace, in her own style, and gets it just right. After hearing her solo work, I discovered that she is touring in the band of a popular artist who - let's be crystal clear - says nothing to me in my life. It would have been a grave mistake if I had allowed that fact to dissuade me from giving this album a chance; it is a contemplative work of elegant dreamscapes, a sound collage, a map of hidden feelings; organically constructed as if the puffy clouds in a clear blue sky had been blown into position by breath from ancestral lips.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

Letters From A Forest uses snippets of conversation, sung and spoken lyrics, simple guitar and piano lines, and (as Christian puts it) fake strings, to create what we can call collage atmospherics. The sum of these parts is a tender sounding album, crammed full of romanticized lyrics with a tough, honest, edge and a wondrous stream of consciousness style. When hearing tracks like the "The Ballad of Martin and Caroline,"—a tale of fates deeply entwined in a doomed love spiral—I felt like I was half napping or jet lagged in a spare room, overhearing friends babbling to one another about deceased acquaintances,musical heroes, old records,chance meetings, and the places where it all happened. As such, Letters is an ode to an array of magnificent and magnificently flawed people (some well known, others characters from local legend). It is a sketchbook of notes, more poetic than pathetic, with a palpably emotional tug, celebrating the contradictory nature of life.

Letters From A Forest uses snippets of conversation, sung and spoken lyrics, simple guitar and piano lines, and (as Christian puts it) fake strings, to create what we can call collage atmospherics. The sum of these parts is a tender sounding album, crammed full of romanticized lyrics with a tough, honest, edge and a wondrous stream of consciousness style. When hearing tracks like the "The Ballad of Martin and Caroline,"—a tale of fates deeply entwined in a doomed love spiral—I felt like I was half napping or jet lagged in a spare room, overhearing friends babbling to one another about deceased acquaintances,musical heroes, old records,chance meetings, and the places where it all happened. As such, Letters is an ode to an array of magnificent and magnificently flawed people (some well known, others characters from local legend). It is a sketchbook of notes, more poetic than pathetic, with a palpably emotional tug, celebrating the contradictory nature of life.

David Christian has been issuing records for a couple of decades or more, mostly as the group Comet Gain (which seems to have existed in an alternate reality close and concurrent to mine, but totally invisible to me), yet much of his music feels like bumping into an old friend and picking up exactly with whatever you were talking about years ago. This release hits with a wave of happy/sad reflection, full of understated emotion and unflinching humor. A highlight among many is "The Ballad of Terry Hall," a heartbreaking ode to the fallen deadpan Specials frontman—also appreciating Martin Duffy from Felt (and one or two others) along the way. Here is an unabashedly enthusiastic appreciation of music and also of being oneself however strange, shy, or weird that may be. Christian illuminates the flip side, too: the undertone of serious melancholy which no one escapes in this life. He clearly has the life experience to sound off the cuff while reeling off detailed evocations of people in a style both nostalgic and unflinchingly frank, and he grasps the minor yet essential paradox of how certain dead end jobs are a fertile breeding ground for sparks of creativity, dreams of stardom, addiction, delusion, theft, and humor.

Examples of the sound and lyrical content: "You Know (With John McKeown)" has the subterranean twang of Phantom Payn Days. "Ribbons For Mickey" celebrates the short life of a bristling local character, with a scar over his eye, "from fighting NF skins* after a Madness gig, but his sister said he fell off a piano stool when he was a kid." Elsewhere, odd rhythms surface. There is a metallic slap to "She Had Sinister Hands" and a tropical twist on "Squirrel Beach Sundown." At times the pace picks up, which adds contrast, but I think mainly because it's the flow, and Christian always goes with it in a very endearing one-take warts and all style.

The sparkling "Someone's Home But Not Mine" has a cosmic feel, and also resembles those times when the computer has opened a separate track to the one you're listening to and the combination sounds great. That sense is a constant here, as tracks echo and bleed over into other tracks in an unpredictable way with speech, strings and plonking keys going back and forth like people answering questions that haven't been asked. On "All My Diaries At Once," David Christian says "you can't talk to your past" but this record is a brilliant kaleidoscopic meditation on his.

*National Front skinheads

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This is the second duo collaboration between Chalk and Rebilly, as the pair previously surfaced with L'état Intermédiaire back in 2018. Their shared history goes back to at least 2012 though, as they teamed up with Vikki Jackman for A Paper Doll's Whisper Of Spring. While details about Tsilla are less scarce than usual due to its release on An'archives rather than Chalk's famously terse Faraway Press imprint, I still know very little about Rebilly other than the fact that he plays the clarinet. Beyond that, I am unwilling to hazard any guesses about who is playing what here, as both artists' contributions are largely blurred into a painterly haze (not entirely unfamiliar territory for Chalk). Far more relevant than the instrumentation is the album's inspiration: engraver Cécile Reims, whose "denuded landscapes," "spiraling abstractions," and "unearthly radiance" may have inspired Chalk's visual art as well. If not, Reims is at least a kindred spirit and her collaborations with Hans Bellmer, Leonor Fini, and Salvador Dali probably make a decent enough consolation prize. Reims's deepest impact on Tsilla may have been upon the process rather than the outcome, however, as the pair set out to honor her "tender weaving of emotional complexity carved with the hand-held and simple tools of artisans" in their own way ("a similar transfiguration of base materials"). Regardless of how it was made, Tsilla is quite a unique album in the Chalk canon, as the best pieces evoke a beautifully nightmarish strain of impressionism.

This is the second duo collaboration between Chalk and Rebilly, as the pair previously surfaced with L'état Intermédiaire back in 2018. Their shared history goes back to at least 2012 though, as they teamed up with Vikki Jackman for A Paper Doll's Whisper Of Spring. While details about Tsilla are less scarce than usual due to its release on An'archives rather than Chalk's famously terse Faraway Press imprint, I still know very little about Rebilly other than the fact that he plays the clarinet. Beyond that, I am unwilling to hazard any guesses about who is playing what here, as both artists' contributions are largely blurred into a painterly haze (not entirely unfamiliar territory for Chalk). Far more relevant than the instrumentation is the album's inspiration: engraver Cécile Reims, whose "denuded landscapes," "spiraling abstractions," and "unearthly radiance" may have inspired Chalk's visual art as well. If not, Reims is at least a kindred spirit and her collaborations with Hans Bellmer, Leonor Fini, and Salvador Dali probably make a decent enough consolation prize. Reims's deepest impact on Tsilla may have been upon the process rather than the outcome, however, as the pair set out to honor her "tender weaving of emotional complexity carved with the hand-held and simple tools of artisans" in their own way ("a similar transfiguration of base materials"). Regardless of how it was made, Tsilla is quite a unique album in the Chalk canon, as the best pieces evoke a beautifully nightmarish strain of impressionism.

The album opens in unexpectedly tense and disturbing fashion with "Pliskiné," as shivering strings quiver in dissonant harmonies over a bed of subtle, slowly shifting drones like a swarm of hallucinatory bees with bad intentions. For better or worse, that particular descent into horror is not a representative one, though Tsilla is quite a dark and uncharacteristically heavy album for Chalk (and presumably for Rebilly as well). "Pliskiné" aside, the album's other deep plunge into nightmare territory is "Hauteville," which feels like a groaning, slow-motion descent into squirming, buzzing cosmic horror at its most exquisite. In general, the longer pieces tend to be the strongest while the shorter pieces feel more like bridges or interludes, though "Visages d'Espagne" is a notable exception that resembles a seasick duet between a koto and a vibrato pedal.

Elsewhere, "L'embouchure Du Temps" is yet another unsettling highlight, as it arguably resembles the curdled and time-stretched sounds of an infernal brass band experienced while in the throes of a fever delirium. I also noted that it sounded more like a cursed fog than a musical composition, which is probably a compliment of sorts. The closing "Retour À Kibarty" is yet another gem and a well-placed one at that, as it almost feels like a vivid sunrise is swelling from the horizon in a doomed but valiant attempt to break the album's spell and burn away all the lingering darkness and murk. That said, if it actually was a sunrise, it would probably be one with a lot of bruised purples and burning oranges, as it is still quite a haunting (and haunted) piece. In fact, it even dissipates like a ghost in the end to helpfully punctuate the disquietingly supernatural feel of Chalk and Rebilly's drones.

Needless to say, the fact that Andrew Chalk has released yet another beautifully realized, richly nuanced, and immersive album should surprise no one at this point in his career, but Tsilla nevertheless stands out as a fascinating outlier due to its unusually dissonant, smeared, and unsettling atmosphere.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

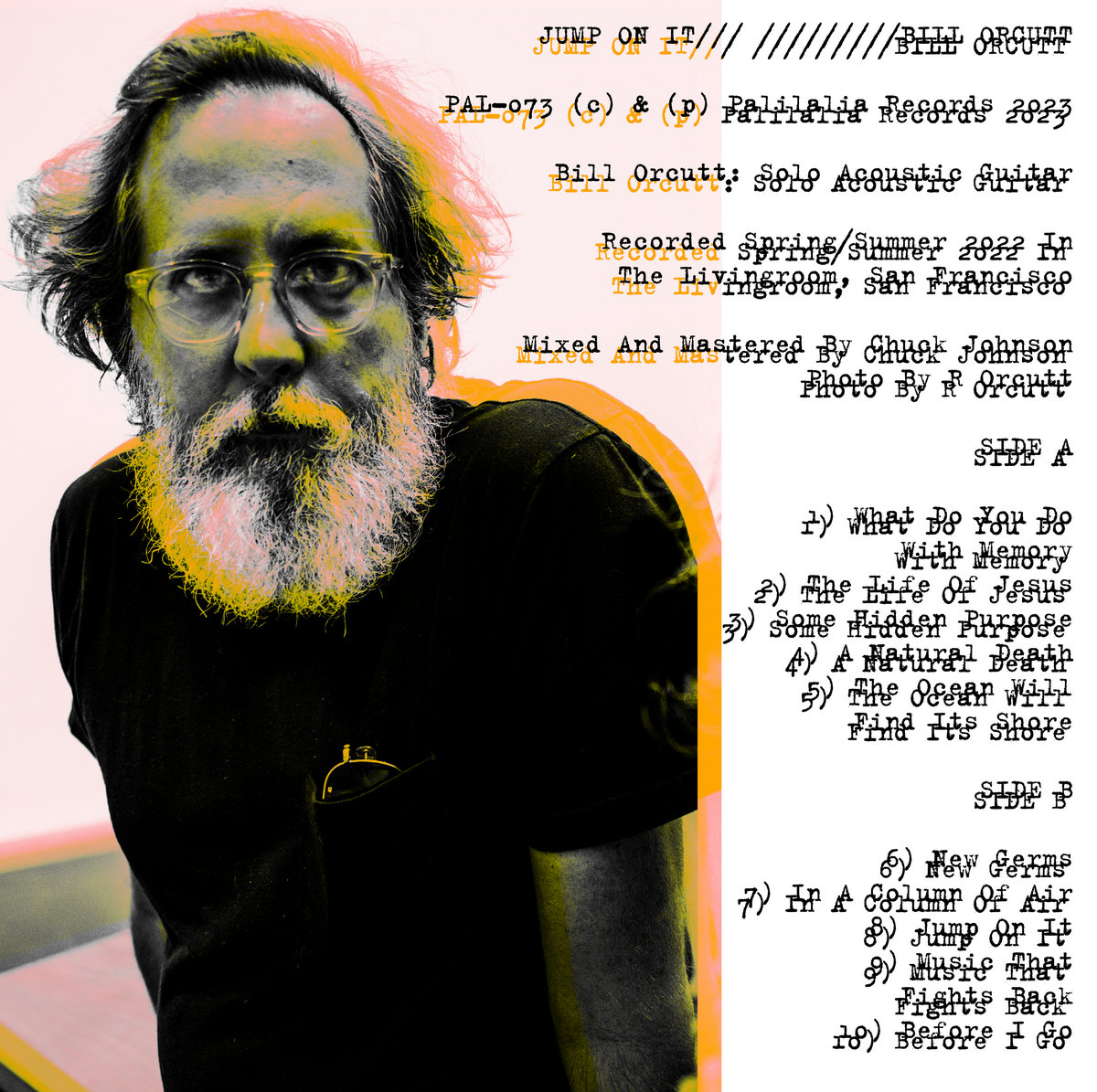

This latest LP from San Francisco-based guitar visionary Bill Orcutt is a spiritual successor of sorts to 2013's A History of Every One, as that was apparently his last solo acoustic guitar album. The resemblance between the two albums largely ends there, however, as Jump On It is as different from the deconstructed standards of History as it is from last week's Chatham-esque guitar quartet performance for NPR. While I do enjoy Orcutt's Editions Mego solo era quite a bit, there is no denying that his artistry has evolved dramatically over the last decade and his recent work definitely connects with me on a deeper level. In more concrete terms, Orcutt's work no longer resembles the choppy, convulsive, and possessed-sounding fare of History, as he has since reined in his more fiery, passionate impulses enough to leave more room for passages of tender, simple beauty. In fact, Jump On It might be the farthest that the balance has swung towards the latter, as the characteristic Orcutt violence is a rare presence in the collection of quietly lovely and spontaneous-sounding guitar miniatures.

This latest LP from San Francisco-based guitar visionary Bill Orcutt is a spiritual successor of sorts to 2013's A History of Every One, as that was apparently his last solo acoustic guitar album. The resemblance between the two albums largely ends there, however, as Jump On It is as different from the deconstructed standards of History as it is from last week's Chatham-esque guitar quartet performance for NPR. While I do enjoy Orcutt's Editions Mego solo era quite a bit, there is no denying that his artistry has evolved dramatically over the last decade and his recent work definitely connects with me on a deeper level. In more concrete terms, Orcutt's work no longer resembles the choppy, convulsive, and possessed-sounding fare of History, as he has since reined in his more fiery, passionate impulses enough to leave more room for passages of tender, simple beauty. In fact, Jump On It might be the farthest that the balance has swung towards the latter, as the characteristic Orcutt violence is a rare presence in the collection of quietly lovely and spontaneous-sounding guitar miniatures.

The album opens in appropriately gorgeous fashion, as the first minute of "What Do You Do With Memory" is devoted to a tender, halting and bittersweet arpeggio motif, though the piece then takes a detour before reprising that wonderful theme for the finale. The detour is admittedly brief, but so is the song itself, which illustrates a central feature of this album: these pieces generally feel like a series of spontaneous snapshots/3-minute vignettes rather than fully formed compositions that build into something more. That is not meant as a critique, but it does mean that Jump On It is something other than Orcutt's next major artistic statement. I am tempted to say that most of this album feels akin to a pleasant but loose improvisation around a campfire, but there are also some pieces that evoke an usually meditative Django Reinhardt playing alone in a late-night hotel room.

The connective tissue between those two poles is, of course, casual virtuosity and that is the most readily apparent trait of Jump On It: it can feel languorous, pensive, and searching at times, but there are plenty of fiery runs, viscerally snapping bends, and surges of passion to keep things compelling and remind me that this is still very much a Bill Orcutt album. To my ears, "The Ocean Will Find Its Shore" is the album's centerpiece, as its early sense of forward motion seamlessly dissipates into a tender reverie before more intense emotions bubble to the surface for a brief but intense crescendo. "In A Column Of Air" is another major highlight, however, as a lyrical minor key melody fitfully winds through scrabbling note flurries, quivering double-stops, emphatic chord sweeps, violent bends, and sundry other dynamic flourishes (and it all ends with a killer repeating riff to boot). Unsurprisingly, the remaining pieces are all enjoyable as well, albeit with the caveat that they generally feel more like sketches or miniatures than fresh, fully articulated masterpieces.

While I still heartily maintain that just about everything released on Orcutt's main Palilalia imprint is compelling and significant, I am quite curious to see how this album in particular is received. It feels like one of his less substantial recent releases to me (particularly in the wake of Music For Four Guitars), yet it also seems like it could reach an atypically wide audience, as Orcutt's characteristically soulful and singular playing is couched in a much more casual and intimate setting than the snarling, incendiary, and more overtly avant-garde fare that he is usually associated with.

Read More