- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Few contemporary industrial acts are spoken of in such highly reverential terms as Alberich, the solo project of underground super-producer Kris Lapke. While Lapke himself may best be known for his production and mastering work, both for such diverse sounding acts like Prurient, Nothing and the Haxan Cloak to his audio restoration work for Coum Transmissions and Shizuka, Alberich has achieved a cult on par with many of the legends he works with.

Lapke's diverse contributions as a producer are recognizable for the perfect balance of maximalist and minimalist electronics that Alberich has relentlessly authored. Since Alberich's 2010 masterful and highly collectable 2.5 hour NATO- Uniformen album, he has become a powerful force of modern industrial music. With only a series of limited tape and split releases, fans have been waiting with bated breath for a true follow-up album. The first full-length Alberich album in almost a decade, Quantized Angel will be released April 12, 2019. In the intervening years between albums, Alberich has grown more nuanced, creating atmosphere and tension on par with Silent Servant's classic Negative Fascination LP in regards to production and attention to detail.

The results create a newly polished but no less intense vision of modern industrial music. Over the course of the album’s eight tracks, Alberich demonstrates a vision of ruthless existential electronics, a sound both commanding yet questioning in introspective spirit.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Consisting of two thirds of the band Ars Phoenix, namely Jonn Gauntletier and Caitlin Grimalkin, it is not overly surprising that there are a lot of similarities between the bands. Both are equally synth heavy and rife with memorable hooks. However, the two are distinct projects, with Pass/Ages mining somewhat darker, distorted territories in comparison to the slightly more up beat Ars Phoenix work. Never are the moments of catchiness far off, however, resulting in a tape that is rough and experimental, yet as memorable as any pop record out there.

Consisting of two thirds of the band Ars Phoenix, namely Jonn Gauntletier and Caitlin Grimalkin, it is not overly surprising that there are a lot of similarities between the bands. Both are equally synth heavy and rife with memorable hooks. However, the two are distinct projects, with Pass/Ages mining somewhat darker, distorted territories in comparison to the slightly more up beat Ars Phoenix work. Never are the moments of catchiness far off, however, resulting in a tape that is rough and experimental, yet as memorable as any pop record out there.

The tape opens on a high note with "As It Rises".Lead by a distorted, dirty synth and pleasantly rigid drum machine, the melodic elements that are added contrast perfectly.With the rhythmic section offset by ghostly synth pads, wobbling leads, and Grimalkin's vocals, the blending of light and dark is perfectly achieved."When the Sky Ignites" is a similar blend, with the vocals treated more and the addition of some excellent throwback syndrum passages.

"Materialize Me" is another great example of the somewhat harsher tendencies of Pass/Ages.The drum machine is bombastic and distorted, and the vocals are mixed to the front and less effected.With the addition of vintage string synth passages, the complete package is a great one.The mix may be sparser, but the thumping bass line of "Possession" balances out the 1980s keyboard leads that result in some extremely catchy melodies.

Other significant portions of this tape feature Pass/Ages opting less for distortion and more for heavy reverb as the primary feature.The ethereal layers of "Taken Underneath" and the complex melodic passages result in a splendidly executed bit of dark pop.There may be some prominent snappy rhythms on "How Much Did You Take?", but its hard to not focus on the beautiful electronic melodies and buried vocals just barely peeking out from the wall of reverb.On both "Asphodel" and "Cavalcade", the duo dial the tempo back into much lower BPMs, but in the process make for two dramatic, anthem-like works of lush production and big, rich synthesizer passages.

The influences on Pass/Ages are clear and rooted deeply in the 1980s, but one of the strongest things about Taken Underneath is how it sounds, from a production standpoint, entirely contemporary.Instead of an intentionally retro aesthetic, the duo takes the inspiration from the era, but no conscious attempt to mimic anything too specifically.  The production also has just the right amount of DIY grime though.By no means is it amateurish, but it lacks the unnatural sheen that would strip it of its unique sound.Taken Underneath is an extremely memorable, distinct album that is a fitting continuation of the Ars Phoenix legacy.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This Australian trio first appeared on my radar with 2015’s somewhat polarizing and aptly named Severe album, which stripped away all of the more conventional post-punk elements of their sound to leave only a beautifully chiseled and pummeling strain of minimalism. I suppose most My Disco albums have been a bit polarizing though, as the band have undergone a series of transformations since their early days as a math-rock band and not every fan has wanted to stick around for the next phase. With Severe, however, it felt like My Disco had finally found a truly distinctive niche that felt like their proper home. Environment happily continues to explore that same vein, yet takes that aesthetic to an even greater extreme, replacing surgical brutality with an ominous, simmering tension and dissolving any last traces of the band’s more "rock" past.  It is hard to say if Environment quite tops Severe, but it is very easy to say that it is another great album from an extremely compelling band.

This Australian trio first appeared on my radar with 2015’s somewhat polarizing and aptly named Severe album, which stripped away all of the more conventional post-punk elements of their sound to leave only a beautifully chiseled and pummeling strain of minimalism. I suppose most My Disco albums have been a bit polarizing though, as the band have undergone a series of transformations since their early days as a math-rock band and not every fan has wanted to stick around for the next phase. With Severe, however, it felt like My Disco had finally found a truly distinctive niche that felt like their proper home. Environment happily continues to explore that same vein, yet takes that aesthetic to an even greater extreme, replacing surgical brutality with an ominous, simmering tension and dissolving any last traces of the band’s more "rock" past.  It is hard to say if Environment quite tops Severe, but it is very easy to say that it is another great album from an extremely compelling band.

Listening to Environment, it is difficult to believe that My Disco were ever a band with clearly defined roles like "drummer" and "guitarist," as they seem very much like an entity that has almost transcended conventional instrumentation entirely.In the opening, "An Intimate Conflict," for example, the trio's palette is reduced to just a thick electronic throb and the sounds of scraping metal.Even Liam Andrews' vocals diverge from traditional territory, as his fitful and indecipherable monologue is enveloped in a squall of distortion and reverb.The insistently pulsing and brooding atmosphere actually calls to mind the power electronics milieu, but My Disco depart from that aesthetic by opting for deadpan cool and unresolved tension rather than misanthropic catharsis.A far more visceral and explosive side of the band certainly exists, but it has been completely exiled to the accompanying remix album, leaving Environment to exist as an unwaveringly focused tour de force of restraint and understated menace.It is also quite an intriguing experiment in stark minimalism, as "Hong Kong 1987" explores a similarly constrained palette of throbbing bass drone mingled with enigmatic metallic scrapes, though it augments that foundation with a ghostly ascending melody.The brief "Equatorial Rainforests of Sumatra" goes to an even greater extreme, taking away everything except for a bass drum and some ritualistic-sounding metal percussion.If I did not know that I was listening to My Disco and someone told me that it was a field recording from a Tibetan funeral or something instead, I would not question it for a second.

The best songs on Environment, however, are the ones where My Disco combine their arsenal of unsettling creaks and throbs with some semblance of consistent rhythm or sense of forward motion. The best of these more conventionally song-like moments is probably "Rival Colour," which augments a half-sinister/ half-sensuous bass throb with an "evil woodpecker" percussion motif that sounds like something I would expect to hear shortly before being murdered by cannibals in a dense, foreboding jungle.The closing "Forever" is a similarly brilliant feast of darkly seductive menace, as a tribal-sounding hand-percussion motif moves unrelentingly forward amidst drizzling rain and Andrews' hushed promises (or threats) that he will wait.Notably, it features the sole moment of volcanic release on the entire album, as there is a howling and gnarled squall of guitar noise shortly before the song dissolves entirely to leave only the lingering sounds of the rain in its wake.Given the quiet intensity and brutally spartan nature of album, however, any glimpse of violence or hint of an imminent eruption is impressively magnified in power.Consequently, I would be remiss if I did not single out "Act" as yet another highlight, which improbably manages to wrest a remarkable amount of brooding intensity out of a single densely buzzing tone that slowly flanges and snarls.I think there are at least three songs on this album constrained to a single repeating or sustained note and all of them are great.That is quite an impressive feat to pull off repeatedly.

As wonderful as it is, however, "Act" does highlight Environment's sole minor flaw: Andrews is a vocalist of very few words.In many cases, it feels like he is using simple repeated phrases in an ingenious way, evoking an unnerving obsessiveness and escalating sense of dread.Other times, it just feels like the lyrics were kind of an afterthought."Act" falls into that latter category.For the most part, however, Environment is a hell of an album and an extremely cool vision executed beautifully. I cannot think of many other bands that so skillfully blur the lines between artistic rigor, tight songcraft, and sounding like they would probably stab me with a broken bottle if I looked at them wrong.Late-period Disappears has also earned a place in that illustrious pantheon and they are probably the closest kindred spirit here, but Environment sounds like the blackened framework that would remain if someone set the Era album on fire.I mean that in the best way possible, as I cannot praise this album's high points enough.At their best, My Disco wield space absolutely brilliantly, creating a vacuum in which every single sound makes a deep impact.Moreover, the band do an incredible job at creating and sustaining a bleakly beautiful and unwaveringly heavy mood without a single lapse or misstep.Environment is the perfect negative image of a great post-punk album, draining away all the color and heightening the contrast to transform the previously familiar into something eerily spectral and nearly unrecognizable.

Samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Hot on the heels of his appearance on last year's In Death's Dream Kingdom, Abul Mogard returns to Houndstooth with a collection of his work as an unlikely remix artist. Of these five lengthy pieces, I was only familiar with the one from Fovea Hex's The Salt Garden II, as his reworkings of songs by Nick Nicely and a pair of Houndstooth artists (Aïsha Devi and Penelope Trappes) somehow eluded me. The beguiling centerpiece of the album, however, is an entirely new work that reimagines Cindytalk/Massimo Pupillo's sublime Becoming Animal project. All of the chosen pieces suit Mogard's aesthetic beautifully though, adding up to an album that is more like an unexpectedly strong and song-based follow-up to Above All Dreams than a collection of one-off works that were never intended to coexist. Naturally, this is easily Abul Mogard's most accessible release to date, but I was pleasantly surprised to discover that it is also one of his best too.

Hot on the heels of his appearance on last year's In Death's Dream Kingdom, Abul Mogard returns to Houndstooth with a collection of his work as an unlikely remix artist. Of these five lengthy pieces, I was only familiar with the one from Fovea Hex's The Salt Garden II, as his reworkings of songs by Nick Nicely and a pair of Houndstooth artists (Aïsha Devi and Penelope Trappes) somehow eluded me. The beguiling centerpiece of the album, however, is an entirely new work that reimagines Cindytalk/Massimo Pupillo's sublime Becoming Animal project. All of the chosen pieces suit Mogard's aesthetic beautifully though, adding up to an album that is more like an unexpectedly strong and song-based follow-up to Above All Dreams than a collection of one-off works that were never intended to coexist. Naturally, this is easily Abul Mogard's most accessible release to date, but I was pleasantly surprised to discover that it is also one of his best too.

I would love to someday hear an Abul Mogard remix that enlivens a beautiful Fovea Hex song with frenetic breakbeats and party horns, but Mogard in remix mode is almost indistinguishable from Mogard performing his own work at this stage of his career: everything he touches is elegantly stretched into a warmly languorous reverie of blurred and frayed chord swells. For the most part, nearly all of these songs fell quite close to that territory before Mogard even started working his signature magic, so his sorcery largely lies in transforming traits that already existed into something a bit more expansive, radiant, and subtly hallucinatory.The sole exception to that trend is the unexpected opener, which is a somewhat radical overhaul of a piece from Aïsha Devi’s 2015 debut album.Notably, Devi's DNA Feelings was all over "best of 2018" lists last year, but Mogard was apparently into her years before that, which is very amusing and endearing if his purported identity as a retired Serbian factory worker is true.The original version of "O.M.A" is a warped, distinctive, and fairly experimental twist on soulful and seductive dance music.The remixed version, on the other hand, is almost unrecognizable, as Devi's voice melodically floats through lush, billowing chords like a beckoning Siren's song.Also, Devi's voice is arguably not even the focal point of the piece, as it drifts in and out while a slow-moving and spacey synth motif establishes itself as the heart of it all.It is a truly lovely piece of music, but so is everything else on the album."O.M.A" just happened to travel a bit further to get to its final destination than the rest of its peers.

Penelope Trappes' brooding "Carry Me" winds up in roughly similar aesthetic territory, but Mogard skillfully manipulates the textures to evoke a slow-burning and ghostly melancholy, emphasizing the ominous throb of the bass notes and imbuing the chords with a colder, more corroded edge.As great as first two songs are, however, the album's most impressive stretch does not come until the one-two punch of Nick Nicely's "London South" and Becoming Animal's "The Sky Is Ever Falling."Both seem like such a perfect fit that it almost seems like it was predestined for them to wind up here.The original "London South" is a beautifully droning and dreamlike bit of bittersweet pop brilliance and Mogard wisely leaves that structure and mood almost entirely intact, opting to merely transform the scale, building it into a gorgeously ragged, warmly enveloping, and achingly dreamlike epic three times as long as its source material.Becoming Animal's aesthetic is perhaps even more fundamentally aligned with Mogard's, as he merely excised the samples from their "Doorway to the Sky," replaced the simmering guitar noise with billowing dark clouds of synth chords and allowed Gordon Sharp's tenderly gorgeous vocals unfold exactly as intended.One could definitely argue that Mogard's remix is merely polishing up a diamond a bit, but it does benefit from the polishing, as the slow-building intensity is a bit more effective and nuanced here (not surprising, given that the original was recorded live at Café Oto).

Amusingly, the one piece that I already knew and liked quite a bit before hearing the album (a reworking of Fovea Hex's "All Those Signs") turned out to be the least of his remix achievements, though it is an appealingly understated and intimate performance.At its core, "We Dream All The Dark Away" is a fundamentally rapturous piece of music, as Mogard marries Clodagh Simonds' simple, lovely vocal melody to a similarly simple and lovely organ motif, elevating the piece into an even more sublime work of tender beauty.Unfortunately, the piece then sprawls out and meanders for over twenty minutes, greatly diluting its impact.Hopefully someone will someday do a remix of the remix, isolating and expanding upon its early brilliance (though it would admittedly take some serious guts to leave Brian Eno’s choral contribution on the cutting room floor).That said, it is still an intermittently gorgeous piece–I just did not expect to be blindsided by so many pieces that were even better.Aside from the remarkably high standard of quality, And We Are Passing Through Silently is also a bit of a revelation for so seamlessly transforming Mogard's heavenly drones into something approaching pop music.The addition of vocals to his vision feels perfectly natural, organic, and right and absolutely none of the crucial essence is sacrificed in the process.With pieces like "London South" and "The Sky is Ever Falling," Mogard makes it seem like he has been doing remixes forever and that it is exactly what he was supposed to be doing all along.

Samples can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Film composer and multi-instrumentalist William Ryan Fritch will release his long-anticipated double album, Deceptive Cadence: Music For Film Volume I & II on May 17th, 2019 via Lost Tribe Sound.

Most of those familiar with Fritch know only of his albums as a singer songwriter or genre-elusive multi-instrumentalist, which truly represent a small fraction of the depth and range of his work. Deceptive Cadence gathers the most remarkable and memorable pieces from Fritch's vast catalog of film compositions. Rather than filling up two volumes with half- assembled film cues and fragmented themes, Fritch has gone to great lengths with Deceptive Cadence to make sure both volumes tell a story, build themes, and create a satisfying full album experience as good as any movie they may have come from. While this music once graced a particular film, show, or commercial, it has all been reimagined, reworked and made whole in post-production to complete the epic narrative of Deceptive Cadence.

Even fans who remember the release of Music for Film Vol. I in 2015 will be in for a serious treat. Rather than simply reissuing the album alongside the newly minted Volume II, Fritch dove back into the first volume, carving away the fat, leaving only the most breathtaking pieces from the original and replacing the rest with assuredly more mature and enduring compositions. The results of this care are astounding. Keeping in place the emotional sophistication and poise of the original, Fritch seamlessly entwines new classical motifs into the existing, enhancing everything for the better. It has provided Volume I with a newfound sense of regality, romance and legend.

While Volume II compliments Volume I exceptionally well, much of the music was selected from more recent films. Volume II eagerly shares the progression of Fritch's work over the last few years, reveling in a newfound subtlety, patience and confidence as his skills as a composer have advanced. There’s a more minimal and spatially aware approach at play here. Quiet and unhurriedness become the heroine of the story. With Volume II, Fritch has been consistently practicing his craft, refining his unique minimalist/maximalist approach to better support the emotional impact of the lead melodies. Dispersed sparingly throughout, are some of the most long-form ambient classical compositions of Fritch's career, offering a wonderful chance for listeners to become immersed in waves of drone-like strings, submerged piano melodies, and light-bending arrangements. Volume II undeniably deepens the well of talent and world-building that Fritch has shared with us thus far, and binds together multiple film works into a complete and captivating whole.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Droneflower is in bloom. The new collaboration between Marissa Nadler and Stephen Brodsky (Cave In, Mutoid Man), is a sprawling and expansive exercise in contrasts. It is the sound of the war between the brutal and the ethereal, the dark and the light, the past and the present, and the real and imagined.

Brodsky met Nadler for the first time in 2014 at Brooklyn’s Saint Vitus Bar when he came to see her play on her July tour, and they quickly became friends. Both of them had been wanting to explore songwriting that didn't fit into their existing projects, and they soon became energized by the prospect of working together. One of the first ideas they discussed was a horror movie soundtrack, and while Droneflower isn’t that, it is a richly cinematic album. It's easy to imagine much of the record set to images, though it wasn't composed that way.

The first song that came together was "Dead West," based around a beautiful acoustic guitar piece Brodsky wrote while living on Spy Pond, just outside of Nadler's home base in Boston. By the time they started working on the song in earnest, Brodsky had moved to Brooklyn. Nadler added lyrics and vocal melodies remotely, and even from a distance it was obvious there was real kismet in the collaboration.

All the songs on Droneflower were recorded in home studios, and they throb with the frisson of that intimate environment. For much of the recording process, Brodsky would stop by the ramshackle studio that Nadler set up in Boston whenever he was in town visiting family. Songs like "For the Sun" were written on the spot there, lyrics and all. The lush ambient pieces "Space Ghost I" and "Space Ghost II" began as Brodsky piano compositions and were later fleshed out by additional instrumentation and Nadler’s inimitable vocals.

Nadler and Brodsky also recorded two cover songs for the album — the epic Guns n' Roses power ballad "Estranged" and Morphine’s beguiling "In Spite of Me." Since childhood, Nadler had been transfixed by the "Estranged" video where Axl Rose swam with dolphins, and she and Brodsky breathe new life into the song here. Their take on "In Spite of Me" is invigorated by a guest appearance from Morphine saxophonist Dana Colley, who ironically didn't play on the original recording but is indispensable on Nadler and Brodsky's version.

Out April 26th on Sacred Bones.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Based upon Ratkje's music created for the ballet ”Sult” (”Hunger") by profiled director Jo Strømgren for the Norwegian National Ballet, this is a departure from records and live settings normally associated with Maja S. K. Ratkje, as we find her placed behind a modified, wiggly and out-of-tune pump organ, singing songs and improvising.

Metal tubes, PVC tubes and a wind machine were built into the organ; guitar strings, a bass string, a resin thread, metal and glass percussion and a bow are also utilized. With little or no previous experience, she had to learn to play the thing live, using both hands and feet at the same time as singing. Maja played live on stage during every performance, but later modified and recorded the music especially for this record, with Frode Haltli co-producing.

It's a freestanding document, an entity of its own, but the atmosphere is very much the same as in the play: the dusty city of Kristiania in the 19th century, the street noises and the sounds. "Hunger" is Norwegian author Knut Hamsun's breakthrough novel from 1890. Partly autobiographical, it describes a starving young man's struggle to make it as a writer in Kristiania (now Oslo). It has been said that the whole modern school of fiction starts with "Hunger," with its themes around mental states and the irrationality of the human mind.

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Voices In My Head is the latest release from the scientist, musician and visual artist Tavishi (Sarmistha Talukdar). Over 9 tracks, she creates a rich, abstract soundscape which explores her in-between status as a foreigner in a country which is hostile to immigrants, a queer woman from a patriarchal Bengali tradition, and an artist-scientist who finds the cold abstractions of academia removed from social reality. Voices In My Head seeks to unite these ruptures in herself and her audience, creating a sense of catharsis and healing.

The album builds and shatters discordant whirls of sound and rhythm, moving between classical Indian tuning and experimental play. "Sitting In A Circle Looking For Corners" layers bells, intimate breaths and pitched cries to show how "the performativeness of expressing gender in a socially acceptable way can be exhausting," Tavishi says. "As if we have to fit something in a square box when the entity is actually circular."

Other tracks are have roots in science. "I Eat Myself Alive" was generated from research data that she published about a process called autophagy, in which cancer cells eats themselves to gain nourishment and survive stressful conditions. Tavishi converted sequences of amino acids into sounds, arranged according to the molecular signaling flowchart. Still, this scientific approach still has a raw, emotional core: "The track is also a reflection on how marginalized members of our society have to often erase parts of themselves to just survive," Tavishi says.

"Satyameva Jayate," a Sanskrit phrase which translates as "Truth triumphs alone," builds into a tumult of repetitive loops and field recordings. "The history, experience and truth of marginalized people is being erased, misrepresented and gaslighted, it can be hard to believe in ourselves," she says. "I made this track to express resilience and that no matter how much our oppressors want to erase our truth, it will triumph in the end."

More information can be found here.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Caterina Barbieri is an Italian composer who explores themes related to machine intelligence and object-oriented perception in sound through a focus on minimalism.

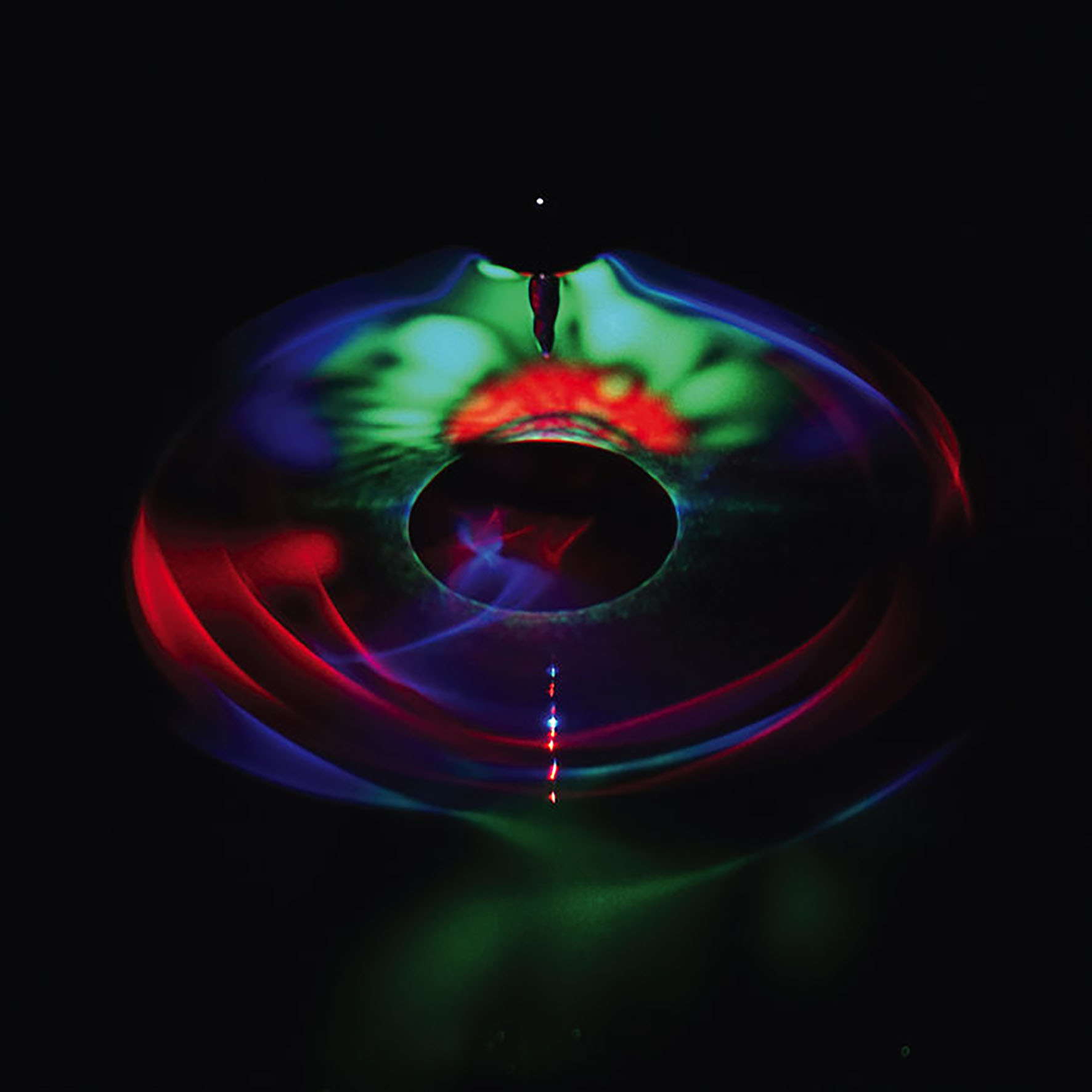

Following 2017’s acclaimed 2LP Patterns of Consciousness, Ecstatic Computation is the new full-length LP by Caterina Barbieri. The album revolves around the creative use of complex sequencing techniques and pattern-based operations to explore the artefacts of human perception and memory processes by ultimately inducing a sense of ecstasy and contemplation. Computation is turned from being a formal, automatic writing technique into a creative, psychedelic practice to generate temporal hallucinations. A state of trance and wonder where the perception of time is distorted and challenged.

Equally nervous and ecstatic, the fast permutation of patterns can create a state where time stands still whilst simultaneously being in motion. Is this propulsive music moving forward or backward? As long as the perception of the present is constantly enhanced and refreshed in an endless sense of loss, re-discovery and the search for self-orientation this question lies mute aside the thrilling and perplexing moment of the matter at hand.

Out May 3rd on Editions Mego.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This latest release is more of a diversion than a fresh addition to the canon of William Basinski masterworks, as it was originally composed for a pair of installations for an exhibition in Berlin. In keeping with theme of the show ("Limits of Knowing"), he stepped outside of his usual working methods to craft floating ambient soundscapes sourced from recordings captured by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Looked at another way, however, On Time Out of Time could be seen as Basinski's normal working methods taken to their ultimate extreme: instead of harvesting sounds from decaying tapes a few decades old, he is now harvesting billion-year-old sounds created by merging black holes. As far as singular, awe-inspiring cosmic events go, that is fairly hard to top, but it must be said that Basinski on his own has a more melodically and harmonically sophisticated sensibility than most (if not all) black holes. As such, the appeal of On Time Out Of Time lies more in the ingenious transformation of the source material than in the finished compositions (though they are quite likable).

This latest release is more of a diversion than a fresh addition to the canon of William Basinski masterworks, as it was originally composed for a pair of installations for an exhibition in Berlin. In keeping with theme of the show ("Limits of Knowing"), he stepped outside of his usual working methods to craft floating ambient soundscapes sourced from recordings captured by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Looked at another way, however, On Time Out of Time could be seen as Basinski's normal working methods taken to their ultimate extreme: instead of harvesting sounds from decaying tapes a few decades old, he is now harvesting billion-year-old sounds created by merging black holes. As far as singular, awe-inspiring cosmic events go, that is fairly hard to top, but it must be said that Basinski on his own has a more melodically and harmonically sophisticated sensibility than most (if not all) black holes. As such, the appeal of On Time Out Of Time lies more in the ingenious transformation of the source material than in the finished compositions (though they are quite likable).

It might be hyperbole to describe it as a golden age, but there was a ten-year stretch that began in the mid-’80s in which Steve Roach, Vidna Obmana, Alio Die, and a few other artists churned out an impressive run of sublime ambient albums.Unusually for a William Basinski release, On Time Out of Time feels like a part of that tradition, albeit the more star-gazing side rather than the tribal/ritualistic side (for obvious reasons, in this case).That is not necessarily a good thing or a bad thing, but it feels like odd territory for Basinski's work to bleed into, as he always seemed more like an art scene guy with considerably different influences than most ambient artists.That stylistic tourism is most evident in the album's epic title piece, though Basinski’s take on space music is an appealingly bleary and impressionistic one.That trait only becomes fully apparent with focused, attentive listening though, as "On Time Out of Time" feels mostly like a time-stretched state of suspended animation, as cold, spectral smears of sound languorously wax and wane to form a shifting haze of vaguely disquieting harmonies.It reminds me of the way a ray of sunlight can sometimes reveal an unseen world of floating dust particles.It would be reductive to say that the piece is merely a vaporous, dreamlike reverie though–it just happens to have an extremely subtle and slow-building arc, quietly blossoming into occasional passages of undulating warmth or darkly lysergic crescendos of blurred dissonance.In general, however, the trajectory is always moving steadily towards greater warmth, culminating in a tenderly lovely final stretch of heavenly chords that dissolves into hissing, clicking near-silence.

The album's considerably shorter second piece ("4(E+D)4(ER=EPR)") is quite a bit different though, returning to more recognizably structured and loop-based territory.As such, it is by far the more instantly gratifying of the two, which is an unfortunate irony: the title piece was clearly the more ambitious and difficult undertaking by a wide margin.By comparison, "4(E+D)4(ER=EPR)" is far more modest in scope, as the ringing deep space transmissions are quickly consumed by a see-sawing pattern of lush, soft-focus chords.While "two alternating chords, endlessly repeated" is theoretically not the strongest theme for a ten-minute composition, Basinski has made a career out of turning the simplest fragments into something poignant and mesmerizing and he does an impressive job of pulling off that feat yet again here.As with the title piece, the magic lies in the details, as there is a swirling, howling, and glimmering storm at the heart of "4(E+D)4(ER=EPR)" that fleetingly breaks through the spaces between the warm chords.The main reason that it works better is simply because there is a consistent pulse to anchor the piece and give it a sense of forward motion (even if it is illusory, as the title track is the one that actually undergoes a significant transformation).

I often have mixed feelings about Basinski's albums that depart from his signature aesthetic of deteriorating tape loops, as he discovered and mastered an ingenious compositional tool that has yielded some absolutely beautiful work.I imagine attempting to compose similarly stellar albums while pointedly avoiding one’s greatest strength is a tricky proposition, but endlessly doing the same thing is doubtlessly a depressing one.It is definitely a balancing act.And as a fairly passionate William Basinski fan, I always feel a bit like a boorish audience member shouting at a brilliant magician to keep doing my favorite trick over and over again whenever I have a lukewarm reaction to something new that he tries.I am delighted that he keeps doing it though.As far as this particular experiment is concerned, On Time Out of Time is a solid album, but it falls short of being one of Basinski's more essential works simply because it sounds exactly like what it was meant to be:the soundtrack to a larger, more complete work.Admittedly, "4(E+D)4(ER=EPR)" stands quite well on its own, but it is a bit too brief to fully immerse me.In any case, On Time Out of Time is best appreciated as a headphone album, as its most exquisite pleasures are nuanced, slowly unfolding ones that reveal themselves only with deep listening.Aside from the source material, that is probably the trait that most makes this a significant and unique addition to Basinski's oeuvre.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This is Simon Scott's formal debut for Touch and it is such a quintessential example of the label's aesthetic that it almost feels like a homecoming. It is similar to a homecoming in another way as well, as Scott composed these pieces from field recordings taken during Slowdive's extensive touring over the last few years, diligently editing and shaping them in hotel rooms during his idle hours. Upon returning, he teamed up with cellist Charlie Campagna and violinist Zachary Paul to transform his impressionistic audio diaries into a lushly beautiful and bittersweet ambient travelogue of sorts. In some ways, this side of Scott's work is less distinctive than his more dub-inflected albums, but he has a remarkably great ear for striking the perfect balance between vibrant textures and blurred, dreamlike elegance.

This is Simon Scott's formal debut for Touch and it is such a quintessential example of the label's aesthetic that it almost feels like a homecoming. It is similar to a homecoming in another way as well, as Scott composed these pieces from field recordings taken during Slowdive's extensive touring over the last few years, diligently editing and shaping them in hotel rooms during his idle hours. Upon returning, he teamed up with cellist Charlie Campagna and violinist Zachary Paul to transform his impressionistic audio diaries into a lushly beautiful and bittersweet ambient travelogue of sorts. In some ways, this side of Scott's work is less distinctive than his more dub-inflected albums, but he has a remarkably great ear for striking the perfect balance between vibrant textures and blurred, dreamlike elegance.

Slowdive's reunion touring led them to a lot of interesting and far-flung locales, but the most striking field recordings that made it onto this album originate from Brisbane, where Scott captured the sounds of a furious wind storm.Those crashing waves and fleeing birds appear prominently in the opening "Hodos," which is Soundings' most striking and evocative marriage of nature and artifice.That is not say that it is necessarily the album's strongest piece, but it is quite a beautiful one, as blossoming dark clouds of brooding strings slowly move across a battered shoreline.The way the spraying whitecaps and the languorously moaning strings interact feels quite organic, natural, and seamlessly intuitive, yet Scott's light touch works so beautifully because he was handed such a wonderful gift: the vibrant and visceral crash of the surf does a hell of a lot of the heavy lifting on its own.On the album's other pieces, the focus is necessarily more on Scott's own contributions (apocalyptic storms were apparently not a common occurrence on the tour).

Most of my favorite pieces fall near the end of the album, but not quite all of them, as the success of "Hodos" is followed by another gem in "Sakura."I am guessing that the gently babbling stream that surfaces in the piece was located somewhere in Japan, but Scott is quite sparing with the background details, largely limiting his contextual clues to the one-word song titles alone.There is a certain logic to that decision, as "Hodos" is the only piece on Soundings where nature has truly earned equal billing.With "Sakura," the beauty originates almost entirely from Scott himself, as the piece unfolds as a flickering and dreamlike reverie of processed guitar sheen. The album’s second (and more sustained) hot streak starts to cohere a few songs later with "Mae," a lazily churning and sizzling drone piece that gradually gives way to a quiet coda of happily chirping birds.Once that avian chorus takes their leave, the album blossoms into a thing of truly sublime beauty with the two pieces that follow: "Grace" and "Nigh."On "Grace," a warm and gently undulating haze of strings twists and drifts across a landscape of shivering and shuddering chord swells.It is an absolutely rapturous piece of music, but "Nigh" is even better still, cohering into a sun-dappled and lovely procession of chord swells mingled with swooning violin melodies and a dreamlike nimbus of subdued flutter and hiss.

For me, those two pieces are the true beating heart and emotional core of the album, but Scott saves a couple of other strong ideas for the album's final act.I am guessing that "Baaval" originated in either Moscow or the Arctic Circle, as both were among Scott's stated recording locations and it is initially a very dark and cold-sounding piece, evoking a windswept expanse of frozen wasteland.By the end, however, it warms into something approaching a sort of precarious radiance, like a faint sunrise chasing away some of the more menacing shadows.That piece gives way to the album’s slow-burning closing epic, the 15-minute "Apricity."For the most part, it marks a warm and lushly beautiful return the terrain of "Nigh," as rich, slow-moving chord swells surge beneath a lovely and lyrical violin melody.As a result, "Apricity" initially seems poised to be the album's crown jewel, but it takes a curious detour around the nine-minute mark and rides out its final third as kind of a locked-groove of gently pulsing, pastoral ambient music.

I am admittedly a bit perplexed as to why Scott chose to dilute one of his strongest pieces in that fashion, as well as end the album on such a comparatively forgettable note.Artists sure can be inscrutable sometimes.Still, it is not nearly enough of a wobble to derail an otherwise excellent album.Soundings is a curious sort of excellent album, however, wonderfully exceeding my expectations some moments and leaving me scratching my head during others.For example, the very restrained and subtle use of field recordings for much of the album feels like an exasperating missed opportunity to me, as Scott could probably have gotten all of the same recognizable sounds without ever leaving southern California.There is nothing among the bird and water recordings that distinctively call to mind Peru, Tokyo, or Moscow, even though Scott recorded in all those places.On another level, however, that decision is actually kind of cool, as Scott eschewed the easy and obvious path to make something considerably more elusive and abstract: a record of his own impressions during a sometimes beautiful, sometimes lonely, sometimes disorienting adventure through many of the great cities of the world.As such, Soundings is a dreamlike procession of elusive individual moments brought to vivid life.Granted, it is easy to imagine a more evocative, richly textured, and immersive album that might have resulted if Scott had taken a more straightforward path, but that album does not exist.This album, however, does exist and it is often an achingly lovely and poignant one.

Read More