Podcast Episode 757, September 10, is live

We enter September with a full episode of new and newly collected/compiled tunes.

New music from Diamanda Galás, The Tear Garden, Volcano The Bear, Kara-Lis Coverdale, Dylan Henner, Weirs, Gary Wilson, Anushka Chkheidze + Robert Lippok, Roméo Poirier, and Andrew Chalk, plus some not quite new music from JG Thirlwell, Ø (Mika Vainio), Laetitia Sonami, and Seefeel.

Thank you to Johnny for the picture in Canada of caribou frolicking in front of the sign for caribou.

Get involved: subscribe, review, rate, share with your friends, send images!

Read more …

I was admittedly a bit blindsided by Dalt's seemingly effortless transformation into an outsider pop chanteuse on 2022's excellent ¡Ay! album and I am amusingly blindsided yet again with this follow up, as she has somehow become even better at balancing her great hooks and sensuous vocals with her wilder, more experimental leanings. In fact, this is unquestionably her finest batch of songs yet, but that achievement is further enhanced by the efforts of some extremely talented and well-chosen collaborators. Notably, Juana Molina, Nick Leon, and Amor Muere's Camille Mandoki all make guest appearances on individual pieces, but it is returning percussionist Alex Lazaro and co-producer David Sylvian who nearly steal the show, as both help elevate Dalt's bold and singular vision into something truly revelatory with their contributions. This is Dalt's strongest album by a goddamn landslide.

I was admittedly a bit blindsided by Dalt's seemingly effortless transformation into an outsider pop chanteuse on 2022's excellent ¡Ay! album and I am amusingly blindsided yet again with this follow up, as she has somehow become even better at balancing her great hooks and sensuous vocals with her wilder, more experimental leanings. In fact, this is unquestionably her finest batch of songs yet, but that achievement is further enhanced by the efforts of some extremely talented and well-chosen collaborators. Notably, Juana Molina, Nick Leon, and Amor Muere's Camille Mandoki all make guest appearances on individual pieces, but it is returning percussionist Alex Lazaro and co-producer David Sylvian who nearly steal the show, as both help elevate Dalt's bold and singular vision into something truly revelatory with their contributions. This is Dalt's strongest album by a goddamn landslide. This reliably fascinating trio is back with a third installment in their excellent Ghosted series. The label describes this one as “a little looser and wilder than before,” which is probably an accurate assessment, but the increased wildness is mostly relegated to Ambarchi’s forays into his table of electronics and effects pedals rather than any kind of larger penchant for volcanic crescendos. To my ears, this album actually feels a bit more subdued and jazz/fusion-inspired than the previous installments, but it also sometimes feels like an album-length expansion of Ghosted II’s strongest piece (“tre”). Given the latter, I would have expected to love this album much more than I do, but it feels like a bit of a mixed bag instead. That said, Ambarchi still has plenty of tricks up his sleeve, so the lesser pieces are interesting enough to (mostly) hold my attention in the long stretch between the album’s two killer highlights.

This reliably fascinating trio is back with a third installment in their excellent Ghosted series. The label describes this one as “a little looser and wilder than before,” which is probably an accurate assessment, but the increased wildness is mostly relegated to Ambarchi’s forays into his table of electronics and effects pedals rather than any kind of larger penchant for volcanic crescendos. To my ears, this album actually feels a bit more subdued and jazz/fusion-inspired than the previous installments, but it also sometimes feels like an album-length expansion of Ghosted II’s strongest piece (“tre”). Given the latter, I would have expected to love this album much more than I do, but it feels like a bit of a mixed bag instead. That said, Ambarchi still has plenty of tricks up his sleeve, so the lesser pieces are interesting enough to (mostly) hold my attention in the long stretch between the album’s two killer highlights. This latest opus from Berlin’s Thomas Ankersmit continues his work with the Serge Modular synthesizer, which is just fine by me, as his last two Serge albums were pure headphone nirvana. Notably, both of those albums were homages of a sort (to Dick Raaijmakers and Maryanne Amacher), but The Dip is simply Thomas Ankersmit being Thomas Ankersmit, which is a significantly different vision. Naturally, many of the familiar sounds of the Serge are back, but the focus has shifted away from spatial movements a bit and more towards “introspective, atmospheric, and even melodic elements.” The result is still an immersive and deeply evocative sound world, but it is a bit less alien this time around and even features a lengthy passage of absolutely sublime beauty.

This latest opus from Berlin’s Thomas Ankersmit continues his work with the Serge Modular synthesizer, which is just fine by me, as his last two Serge albums were pure headphone nirvana. Notably, both of those albums were homages of a sort (to Dick Raaijmakers and Maryanne Amacher), but The Dip is simply Thomas Ankersmit being Thomas Ankersmit, which is a significantly different vision. Naturally, many of the familiar sounds of the Serge are back, but the focus has shifted away from spatial movements a bit and more towards “introspective, atmospheric, and even melodic elements.” The result is still an immersive and deeply evocative sound world, but it is a bit less alien this time around and even features a lengthy passage of absolutely sublime beauty. With a handful of cassettes and CDr EPs released so far, Australian composer Felicity Mangan's first full-length vinyl LP presents a further refinement of her compositional style, blending natural recordings with electronic instrumentation to excellent effect. While on paper her approach may seem rather conventional for the genre, the final product is something much more distinct, engaging, and adventurous.

With a handful of cassettes and CDr EPs released so far, Australian composer Felicity Mangan's first full-length vinyl LP presents a further refinement of her compositional style, blending natural recordings with electronic instrumentation to excellent effect. While on paper her approach may seem rather conventional for the genre, the final product is something much more distinct, engaging, and adventurous.

Compared to some of his recent works, Serenade is more of a collection of miniatures from Sheffield. A single LP of 12 pieces, it is a departure from the 20+ minute works on Don't Ever Let Me Know, or Moments Lost. He leverages this shorter duration effectively, however. Instead of creating monolithic pieces that slowly evolve, he processes and shapes commercial recordings in a multitude of different ways that can differ from song to song, allowing for a wider variety of tones and textures throughout.

Compared to some of his recent works, Serenade is more of a collection of miniatures from Sheffield. A single LP of 12 pieces, it is a departure from the 20+ minute works on Don't Ever Let Me Know, or Moments Lost. He leverages this shorter duration effectively, however. Instead of creating monolithic pieces that slowly evolve, he processes and shapes commercial recordings in a multitude of different ways that can differ from song to song, allowing for a wider variety of tones and textures throughout. This is the debut full-length from the duo of Rachika Nayar and Nina Keith, who previously collaborated on a single back in 2021. Notably, I am a big fan of Nayar’s early guitar-centric releases (Our Hands Across The Dusk and Fragments), but she lost me a bit with the “maximalist synths, sub-bass, and Amen breaks” of her 2022 breakout album Heaven Come Crashing (I am definitely in the minority on that one). Consequently, I had some legitimate trepidation about where Nayar would head next. This is my first encounter with Nina Keith, however, and it definitely will not be my last. All bets are off when these two team up.

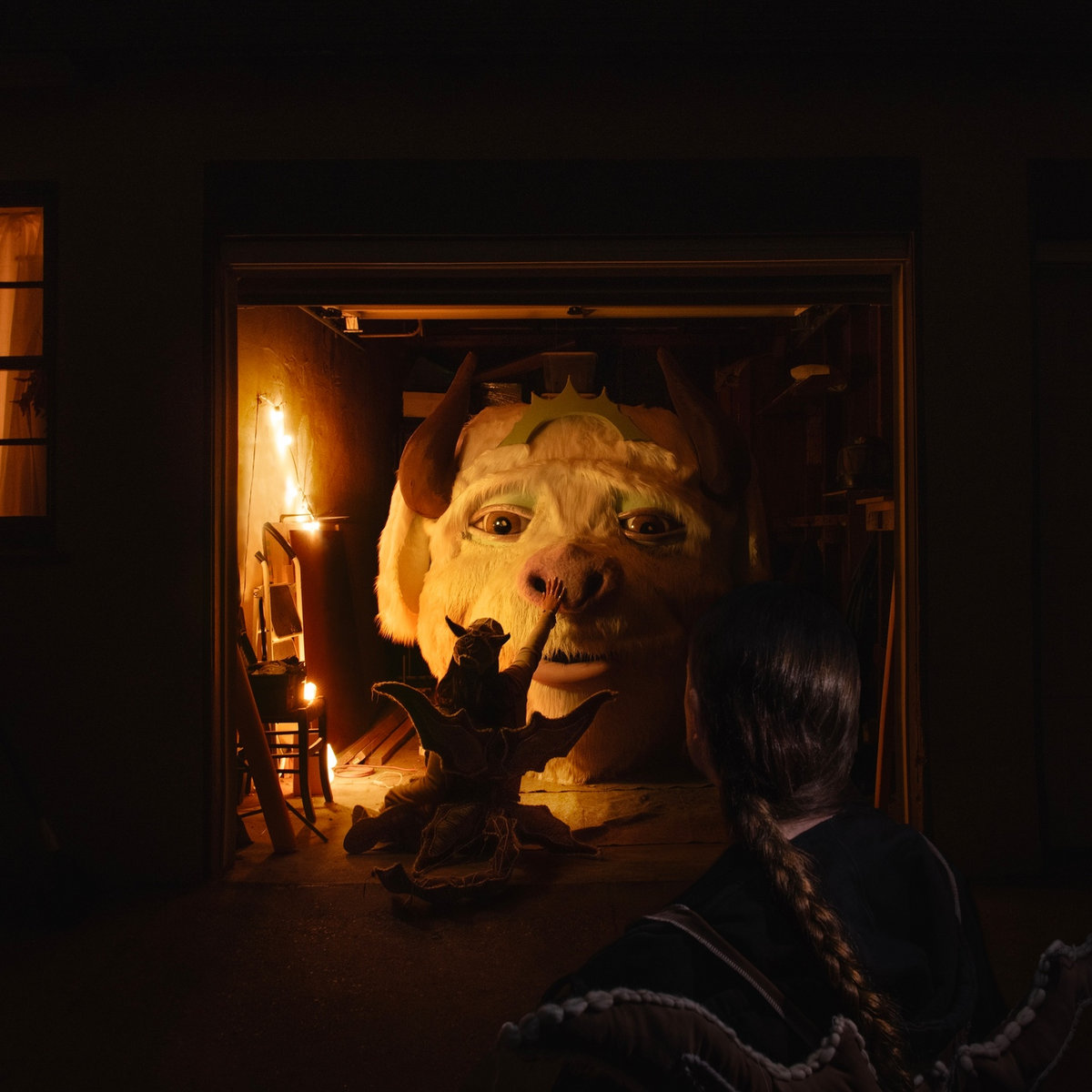

This is the debut full-length from the duo of Rachika Nayar and Nina Keith, who previously collaborated on a single back in 2021. Notably, I am a big fan of Nayar’s early guitar-centric releases (Our Hands Across The Dusk and Fragments), but she lost me a bit with the “maximalist synths, sub-bass, and Amen breaks” of her 2022 breakout album Heaven Come Crashing (I am definitely in the minority on that one). Consequently, I had some legitimate trepidation about where Nayar would head next. This is my first encounter with Nina Keith, however, and it definitely will not be my last. All bets are off when these two team up. This is the debut release from the Norwegian duo of Espen Friberg and Jenny Berger Myhre. The pair previously worked together during the recording of Friberg’s solo debut Sun Soon (Hubro, 2022), as Berger Myhre helped out with production and arrangements. During those sessions, the pair discovered that they shared a “playful, intentionally naive approach towards making art” and Flutter Ridder was born.

This is the debut release from the Norwegian duo of Espen Friberg and Jenny Berger Myhre. The pair previously worked together during the recording of Friberg’s solo debut Sun Soon (Hubro, 2022), as Berger Myhre helped out with production and arrangements. During those sessions, the pair discovered that they shared a “playful, intentionally naive approach towards making art” and Flutter Ridder was born. When I first learned about this release, I was stoked that Madeleine Johnston had enlisted Matt Jencik as a collaborator for the latest Midwife album, as I am a big fan of his 2019 album Dream Character. As it turns out, however, the actual situation was the reverse of that, as Jencik had decided to step outside his ambient drone comfort zone six years ago to record an album of vocal pieces centered around the theme of mortality. Things did not work out quite as planned, however, as Jencik first embarked upon this project with an entirely different collaborator. It feels like destiny that he ultimately wound up working with Johnston instead, however, as the two have a wonderfully complementary yin/yang relationship both stylistically (close mic’d basement 4-track intimacy vs. elegantly sculpted hiss and distortion) and philosophically (Jencik feels a desperate desire to hold onto everyone he loves, while Johnston sees the spectre of death as an “incentive to live more keenly and dearly”).

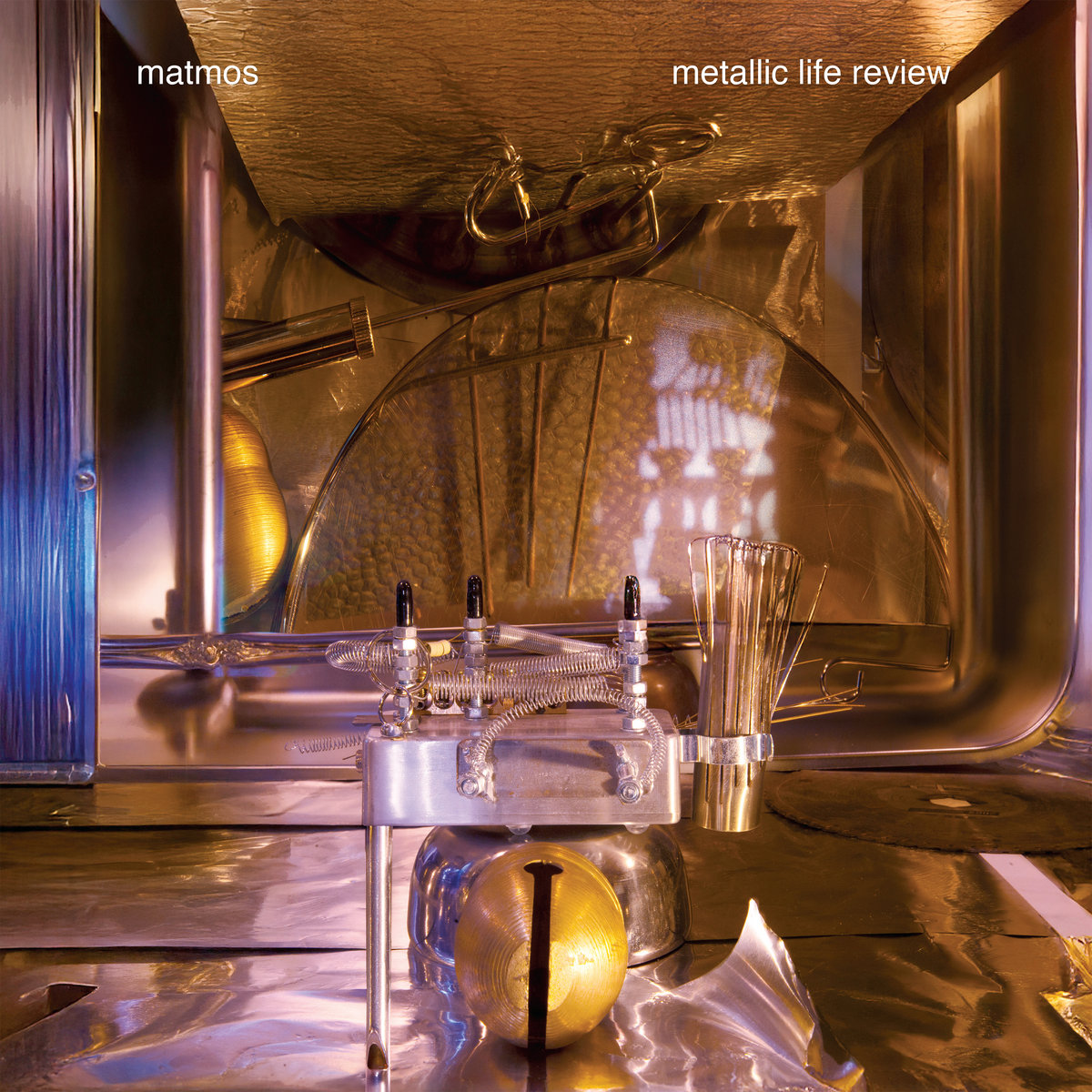

When I first learned about this release, I was stoked that Madeleine Johnston had enlisted Matt Jencik as a collaborator for the latest Midwife album, as I am a big fan of his 2019 album Dream Character. As it turns out, however, the actual situation was the reverse of that, as Jencik had decided to step outside his ambient drone comfort zone six years ago to record an album of vocal pieces centered around the theme of mortality. Things did not work out quite as planned, however, as Jencik first embarked upon this project with an entirely different collaborator. It feels like destiny that he ultimately wound up working with Johnston instead, however, as the two have a wonderfully complementary yin/yang relationship both stylistically (close mic’d basement 4-track intimacy vs. elegantly sculpted hiss and distortion) and philosophically (Jencik feels a desperate desire to hold onto everyone he loves, while Johnston sees the spectre of death as an “incentive to live more keenly and dearly”).  This latest release from the duo of M.C. Schmidt and Drew Daniel is billed as a “compressed fast-forward of Matmos’ career with a sonic parade of the metallic objects from their lives,” as they attempted to mimic the psychological phenomenon of “life review” that people experience during near-death experiences, but quixotically decided to do it exclusively through metallic sound sources. Naturally, that constraint resulted in quite an eclectic and interesting instrumental palette that ranges from “pots and pans from each member’s childhood” to metal reels used in the recording of iconic early musique concrète pieces at Paris's INA/GRM. Notably, however, this album is a bit less uncompromisingly purist than I expected, as the late Susan Alcorn contributed pedal steel to a couple of pieces (still technically metal though).

This latest release from the duo of M.C. Schmidt and Drew Daniel is billed as a “compressed fast-forward of Matmos’ career with a sonic parade of the metallic objects from their lives,” as they attempted to mimic the psychological phenomenon of “life review” that people experience during near-death experiences, but quixotically decided to do it exclusively through metallic sound sources. Naturally, that constraint resulted in quite an eclectic and interesting instrumental palette that ranges from “pots and pans from each member’s childhood” to metal reels used in the recording of iconic early musique concrète pieces at Paris's INA/GRM. Notably, however, this album is a bit less uncompromisingly purist than I expected, as the late Susan Alcorn contributed pedal steel to a couple of pieces (still technically metal though). On her first vinyl LP release, multidisciplinary artist Susana López presents four compositions that blend synths, field recordings, and other sounds treated into pure abstraction. Layered and processed, they are reassembled into compositions that are quite beautiful yet have an alien quality to them that makes them all the more engaging.

On her first vinyl LP release, multidisciplinary artist Susana López presents four compositions that blend synths, field recordings, and other sounds treated into pure abstraction. Layered and processed, they are reassembled into compositions that are quite beautiful yet have an alien quality to them that makes them all the more engaging.