This lovely and unexpected collaboration was quietly released digitally in November with no background information provided at all, but it is probably safe to say that it was recorded quite recently, as it shares a lot of common ground with the radiant drones of Growing's Diptych (2021). That, of course, also means that Gainer can sometimes feel like a welcome throwback to "classic Kranky" era drone artists like Stars of the Lid, though each piece ultimately blossoms into something more ambitious and distinctive by the end. That drone-heavy aesthetic sometimes makes figuring out where Lattimore fits in quite a challenge, as recognizable harp sounds are a bit of a rarity amidst the smoldering bass thrum and ambient shimmer. Then again, recognizable guitar and bass sounds are not exactly rampant either, so maybe all three artists opted for elegantly blurred impressionist abstraction. In any case, whatever they did worked quite well, as Lattimore and Growing's two aesthetics bleed together quite nicely and often feel like something greater than the mere sum of their parts (or at least like a very good Growing album beautifully enhanced with subtle acoustic shadings and flickers of melody).

This lovely and unexpected collaboration was quietly released digitally in November with no background information provided at all, but it is probably safe to say that it was recorded quite recently, as it shares a lot of common ground with the radiant drones of Growing's Diptych (2021). That, of course, also means that Gainer can sometimes feel like a welcome throwback to "classic Kranky" era drone artists like Stars of the Lid, though each piece ultimately blossoms into something more ambitious and distinctive by the end. That drone-heavy aesthetic sometimes makes figuring out where Lattimore fits in quite a challenge, as recognizable harp sounds are a bit of a rarity amidst the smoldering bass thrum and ambient shimmer. Then again, recognizable guitar and bass sounds are not exactly rampant either, so maybe all three artists opted for elegantly blurred impressionist abstraction. In any case, whatever they did worked quite well, as Lattimore and Growing's two aesthetics bleed together quite nicely and often feel like something greater than the mere sum of their parts (or at least like a very good Growing album beautifully enhanced with subtle acoustic shadings and flickers of melody).

The album is divided into two longform pieces that each clock in around 16 or 17 minutes. The opening "Flowers in the Center Lane Sway" fades quietly into being with a slow melody of harmonic-like swells. Around the 2-minute mark, however, the piece unexpectedly blossoms into a far more harmonically and texturally rich chord progression. Given that this partially a Growing album, there is a healthy amount of amplifier hum and buzzing drone waves as well, which provides a pleasantly bleary and immersive backdrop for a simple, seesawing melody that evokes the faint streaks of light from the final moments of a vivid sunset. Occasionally, there is a hint of audible harp or the sensation of something harp-like moving amidst the hum, but Lattimore finally appears in earnest for the piece's final third to add rippling and ephemeral arpeggios that feel like glimpses of twinkling stars in the gaps between passing clouds. As all that happens, the piece sneakily accumulates a pleasantly heaving and hypnotic pulse as well, which is a damn neat trick. It is solid piece, but the following "Tagada, Night Rises" is both stronger and more distinctive. Lattimore initially seems to be steering the ship for the piece, as quivering webs of arpeggios streak lazy trails across a smoldering backdrop of bass drone. Rather than feeling like it is evolving toward something larger, however, the piece lingers in a warm and glimmering dreamscape akin to a state of suspended animation (though the bass drone does seem to be stealthily building in intensity throughout the piece). "Tagada" takes a surprise detour around the halfway point though, as it feels like a menacing vibrato has curdled the bass drone and cast a shadow of uneasy dissonance across everything. That darkening paves the way for yet another composition trick, however, as the piece slowly brightens for a warmly lovely crescendo of woozy and quavering guitar and harp motifs before ending with unexpectedly gorgeous outro that feels like dark birds silhouetted by a deep red sunset. While I suspect both pieces will resonate more with fans of Growing's dronier side than with Lattimore's own fanbase, Gainer is both an impressively organic/seamless convergence of visions and a sustained, quietly beautiful reverie.

Samples can be found here.

I began 2021 not knowing a single goddamn thing about Jeremie Sauvage, the Standard In-Fi label, or France's fascinating Auvergnat/avant-folk milieu, but I am certainly ending the year as a somewhat obsessed fan. Weirdly, this year was not an especially prolific year for the milieu, though Yann Gourdon and Sourdure had fresh releases, yet this album, the Sourdure album, and a pair of France reissues seemed to reach a lot more ears than usual and two of those ears were mine. The linguistically astute may successfully deduce that Quattro is Tanz Mein Herz's fourth album, but details beyond that are minimal and the recordings actually date from a two-day "public recording session" back in 2016 (the band's entire discography seems to have been recorded between 2014 and 2016, in fact). There is also some poetic information provided in French that makes repeated references to drones, vibrations, resonance, infinity, suspension, immensity, and a "pendulum of dreams," which I found both apt and predictably alluring. Admittedly, many of those descriptors could also apply to a host of disappointing drone albums, but I suspect the "pendulum of dreams" bit is probably the secret ingredient that makes this particular album so transcendent. That said, Quattro can also be quite challenging at times, but it unquestionably captures a very unusual acoustic drone ensemble at the very height of their eclectic and hypnotic powers, so it invariably winds up somewhere compelling no matter how prickly the voyage may become along the way.

I began 2021 not knowing a single goddamn thing about Jeremie Sauvage, the Standard In-Fi label, or France's fascinating Auvergnat/avant-folk milieu, but I am certainly ending the year as a somewhat obsessed fan. Weirdly, this year was not an especially prolific year for the milieu, though Yann Gourdon and Sourdure had fresh releases, yet this album, the Sourdure album, and a pair of France reissues seemed to reach a lot more ears than usual and two of those ears were mine. The linguistically astute may successfully deduce that Quattro is Tanz Mein Herz's fourth album, but details beyond that are minimal and the recordings actually date from a two-day "public recording session" back in 2016 (the band's entire discography seems to have been recorded between 2014 and 2016, in fact). There is also some poetic information provided in French that makes repeated references to drones, vibrations, resonance, infinity, suspension, immensity, and a "pendulum of dreams," which I found both apt and predictably alluring. Admittedly, many of those descriptors could also apply to a host of disappointing drone albums, but I suspect the "pendulum of dreams" bit is probably the secret ingredient that makes this particular album so transcendent. That said, Quattro can also be quite challenging at times, but it unquestionably captures a very unusual acoustic drone ensemble at the very height of their eclectic and hypnotic powers, so it invariably winds up somewhere compelling no matter how prickly the voyage may become along the way. Klara Lewis has been a unique and consistently interesting artist ever since she first surfaced, but 2020's Ingrid felt like a massive breakthrough and just about everything that she has released since has been stellar (live albums included). Unsurprisingly, Live in Montreal 2018 does nothing to derail that streak, but there are a couple of somewhat big surprises with it too. The first one is the date of the performance, as I had no idea that Lewis was on this plane two years before Ingrid came along. That is not to say that Live in Montreal would have necessarily eclipsed 2016's excellent Too had it been the follow up, but the Lewis of 2016 was an artist who seemed categorically disinterested in doing anything the conventional/expected way. And the comparative melodicism of 2018's fitfully great collaboration with Simon Fisher Turner (Care) felt like a one-off experiment in applying her non-musical found sounds to a more traditionally musical vision rather than a change in direction. As it turns out, however, Care was merely a tease of greater things to come and the lucky attendees of this performance got a sneak preview of those greater things long before the rest of us. The second big surprise is that this album is composed of seemingly all new material rather than variations on Lewis's existing work—it feels aesthetically akin to a proto-Ingrid, but a stage before that piece was distilled to just a single perfect motif. Obviously, that narrowing of focus yielded great results, but this more varied and shapeshifting approach yielded some legitimately great results too, elegantly blurring the lines between drone, noise, spacy synth explorations, and pop plunderphonics.

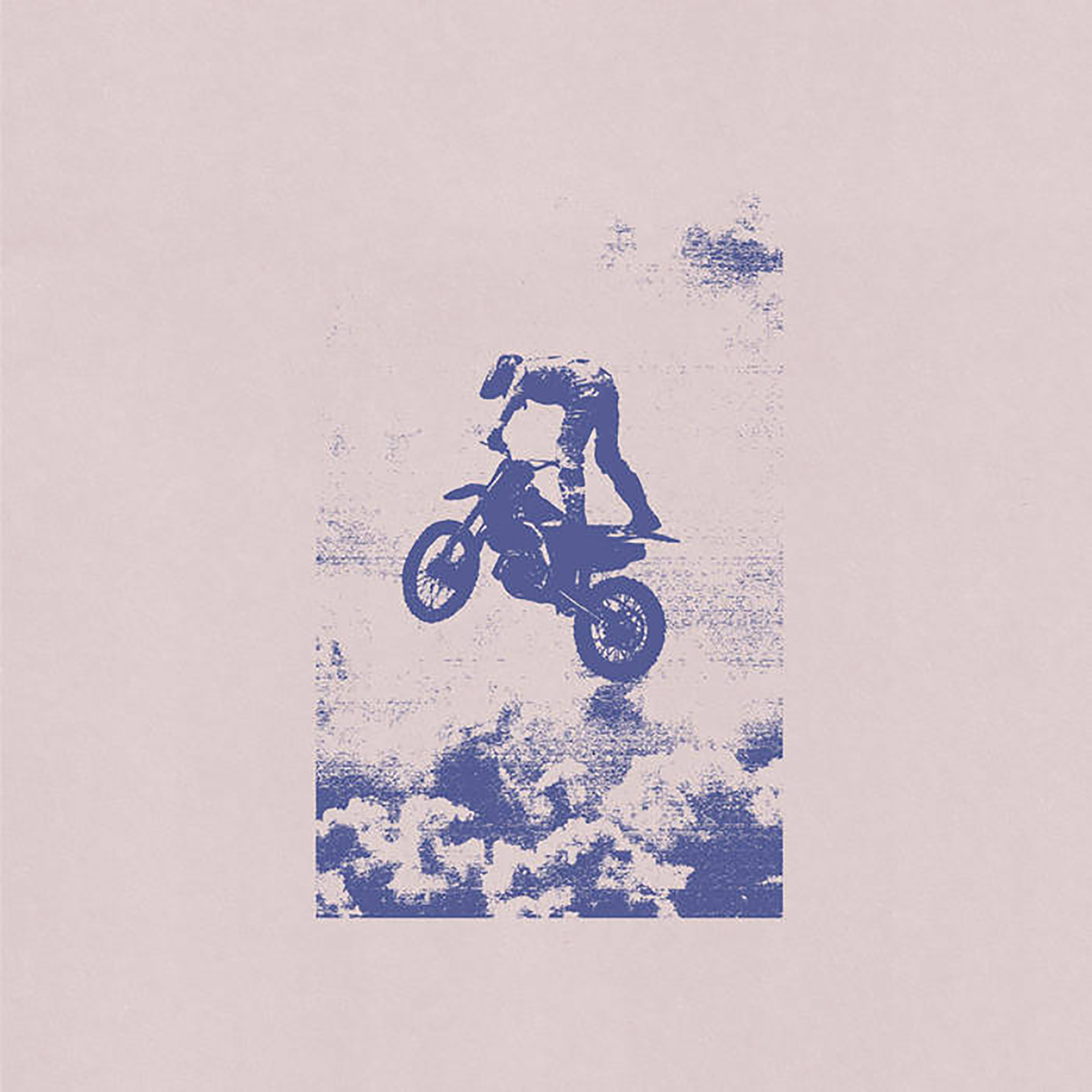

Klara Lewis has been a unique and consistently interesting artist ever since she first surfaced, but 2020's Ingrid felt like a massive breakthrough and just about everything that she has released since has been stellar (live albums included). Unsurprisingly, Live in Montreal 2018 does nothing to derail that streak, but there are a couple of somewhat big surprises with it too. The first one is the date of the performance, as I had no idea that Lewis was on this plane two years before Ingrid came along. That is not to say that Live in Montreal would have necessarily eclipsed 2016's excellent Too had it been the follow up, but the Lewis of 2016 was an artist who seemed categorically disinterested in doing anything the conventional/expected way. And the comparative melodicism of 2018's fitfully great collaboration with Simon Fisher Turner (Care) felt like a one-off experiment in applying her non-musical found sounds to a more traditionally musical vision rather than a change in direction. As it turns out, however, Care was merely a tease of greater things to come and the lucky attendees of this performance got a sneak preview of those greater things long before the rest of us. The second big surprise is that this album is composed of seemingly all new material rather than variations on Lewis's existing work—it feels aesthetically akin to a proto-Ingrid, but a stage before that piece was distilled to just a single perfect motif. Obviously, that narrowing of focus yielded great results, but this more varied and shapeshifting approach yielded some legitimately great results too, elegantly blurring the lines between drone, noise, spacy synth explorations, and pop plunderphonics. As far as I am concerned, Konstantinos Soublis earned a lifetime pass as dub techno royalty with his early Chain Reaction work (the likes of which enjoyed a well-deserved renaissance when Type reissued Vibrant Forms in 2013). Much like fellow visionary Moritz von Oswald, however, Soublis has a creatively restless spirit that has led him in a number of different directions since that scene's late '90s/early '00s golden age came to an end. While I cannot say that I have been a fan of all of Fluxion's various detours over the years, Soublis's unpredictably hit-or-miss discography has continued to surprise me with a legitimate hit every few years. In fact, Fluxion has been in unusually fine form recently and that upswing seems to have culminated in this album, which is unexpectedly one of the most uniformly strong and inspired releases in the project's entire oeuvre. Part of that success is likely due to Soublis's decision to take his vision in a more intimate and inwardly inspired direction (the album was inspired by "real life moments, people, expectations, joy, dreams and disappointments"), but the primary appeal of Parallel Moves is that his new inspirations manifested themselves in quite a killer batch of unusually sensual, soulful, and melodic songs. To my ears, this is a very strong contender for the best Fluxion album ever released.

As far as I am concerned, Konstantinos Soublis earned a lifetime pass as dub techno royalty with his early Chain Reaction work (the likes of which enjoyed a well-deserved renaissance when Type reissued Vibrant Forms in 2013). Much like fellow visionary Moritz von Oswald, however, Soublis has a creatively restless spirit that has led him in a number of different directions since that scene's late '90s/early '00s golden age came to an end. While I cannot say that I have been a fan of all of Fluxion's various detours over the years, Soublis's unpredictably hit-or-miss discography has continued to surprise me with a legitimate hit every few years. In fact, Fluxion has been in unusually fine form recently and that upswing seems to have culminated in this album, which is unexpectedly one of the most uniformly strong and inspired releases in the project's entire oeuvre. Part of that success is likely due to Soublis's decision to take his vision in a more intimate and inwardly inspired direction (the album was inspired by "real life moments, people, expectations, joy, dreams and disappointments"), but the primary appeal of Parallel Moves is that his new inspirations manifested themselves in quite a killer batch of unusually sensual, soulful, and melodic songs. To my ears, this is a very strong contender for the best Fluxion album ever released.

This is the debut album from a "network of New England string pluckers, organ drivers and bell ringers" centered around composer/pedal steel guitarist Henry Birdsey. This is my first real encounter with Birdsey's work, though I was vaguely aware of his duo Tongue Depressor with Crazy Doberman's Zach Rowdan. While I do not get the usual otherworldly "Just Intonation" vibe from Country Tropics' buzzing and layered harmonies, unconventional tunings have historically been a central theme in Birdsey's work, so that may be an element here too. Then again, Old Saw seems like a very different project than Birdsey's usual fare in one very significant way, as Country Tropics is billed as a unique strain of devotional music. I believe it is a secular one, however, as the album description claims "Old Saw points our gaze downward towards the terrafirma unconsidered, and guides our hands into the dirt" rather than towards a "fantastical, celestial vision of understanding." Regardless of their inspirations, Old Saw is an ensemble like no other, approximating a rustic drone or free folk ensemble like Pelt or Vibracathedral Orchestra in an especially warm and transcendent mood (albeit not so warm and transcendent as to preclude some welcome sharp edges, shadows of dissonance, and heavy buzzing strings). This is quite an excellent and unique album.

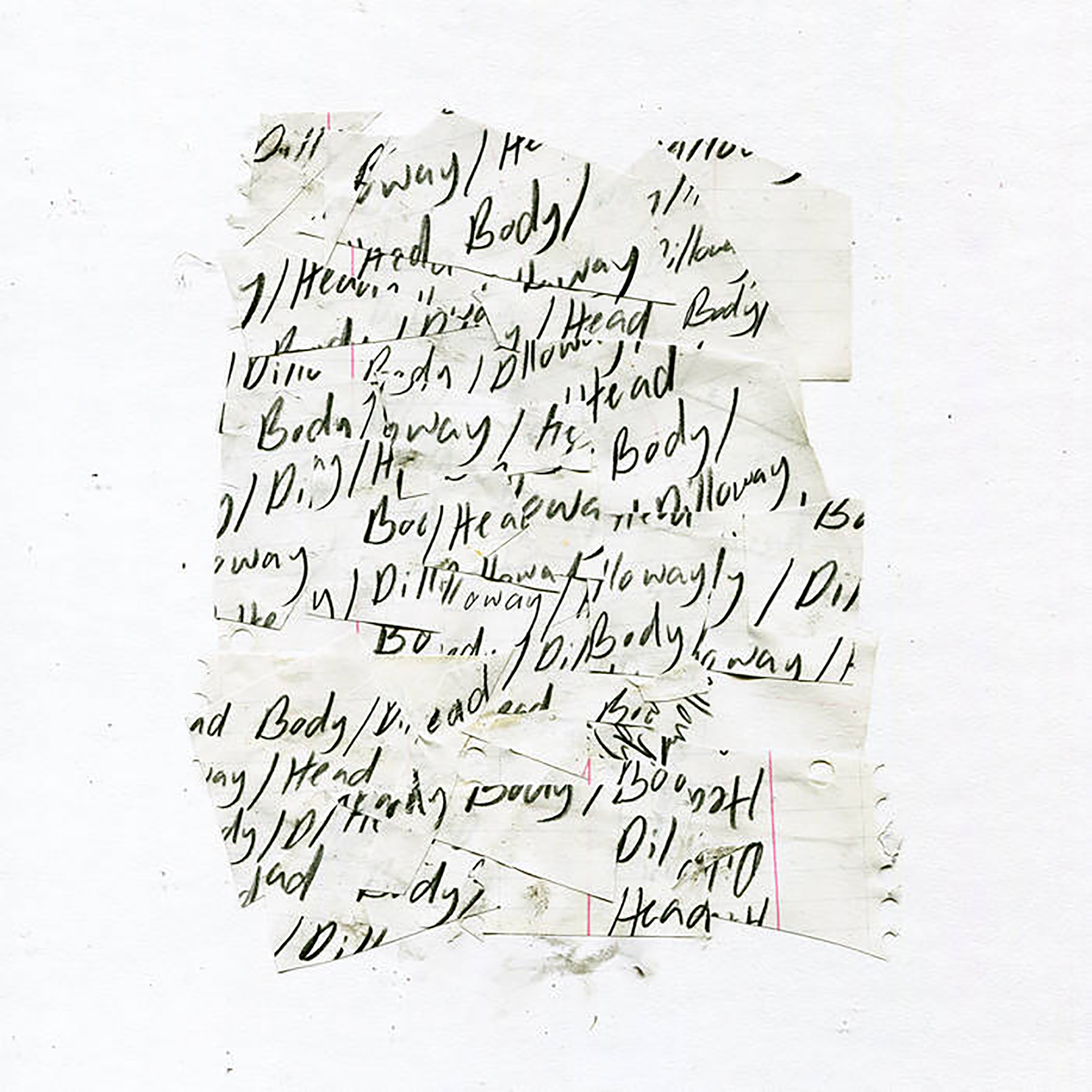

This is the debut album from a "network of New England string pluckers, organ drivers and bell ringers" centered around composer/pedal steel guitarist Henry Birdsey. This is my first real encounter with Birdsey's work, though I was vaguely aware of his duo Tongue Depressor with Crazy Doberman's Zach Rowdan. While I do not get the usual otherworldly "Just Intonation" vibe from Country Tropics' buzzing and layered harmonies, unconventional tunings have historically been a central theme in Birdsey's work, so that may be an element here too. Then again, Old Saw seems like a very different project than Birdsey's usual fare in one very significant way, as Country Tropics is billed as a unique strain of devotional music. I believe it is a secular one, however, as the album description claims "Old Saw points our gaze downward towards the terrafirma unconsidered, and guides our hands into the dirt" rather than towards a "fantastical, celestial vision of understanding." Regardless of their inspirations, Old Saw is an ensemble like no other, approximating a rustic drone or free folk ensemble like Pelt or Vibracathedral Orchestra in an especially warm and transcendent mood (albeit not so warm and transcendent as to preclude some welcome sharp edges, shadows of dissonance, and heavy buzzing strings). This is quite an excellent and unique album. Past experience has taught me not to get too excited about promising-sounding collaborations between great artists, but the allure of this particular project was admittedly damn hard to resist: Body/Head is consistently the most provocative and intense of Sonic Youth's descendants and Aaron Dilloway seems absolutely incapable of releasing a disappointing album these days. Still, there is never any way to predict which threads will assert their dominance when distinctive visions collide, so there are a number of possible shapes that this album could have taken. To my ears, it is Dilloway's broken, murky, and obsessively looping aesthetic that mostly steers the ship, but the balance between the three artists is sufficiently unpredictable and shifting to make this trio feel like something quite different from either Dilloway's solo work or past Body/Head releases. Matt Krefting already did a fine job of summarizing the trio's shared vision with "over and over one gets the sense that the music is trying to wake itself from a dream," but it is also more than that, as this trio have a real knack for slowly transforming gnarled and challenging introductory themes into unexpected passages of sublime beauty.

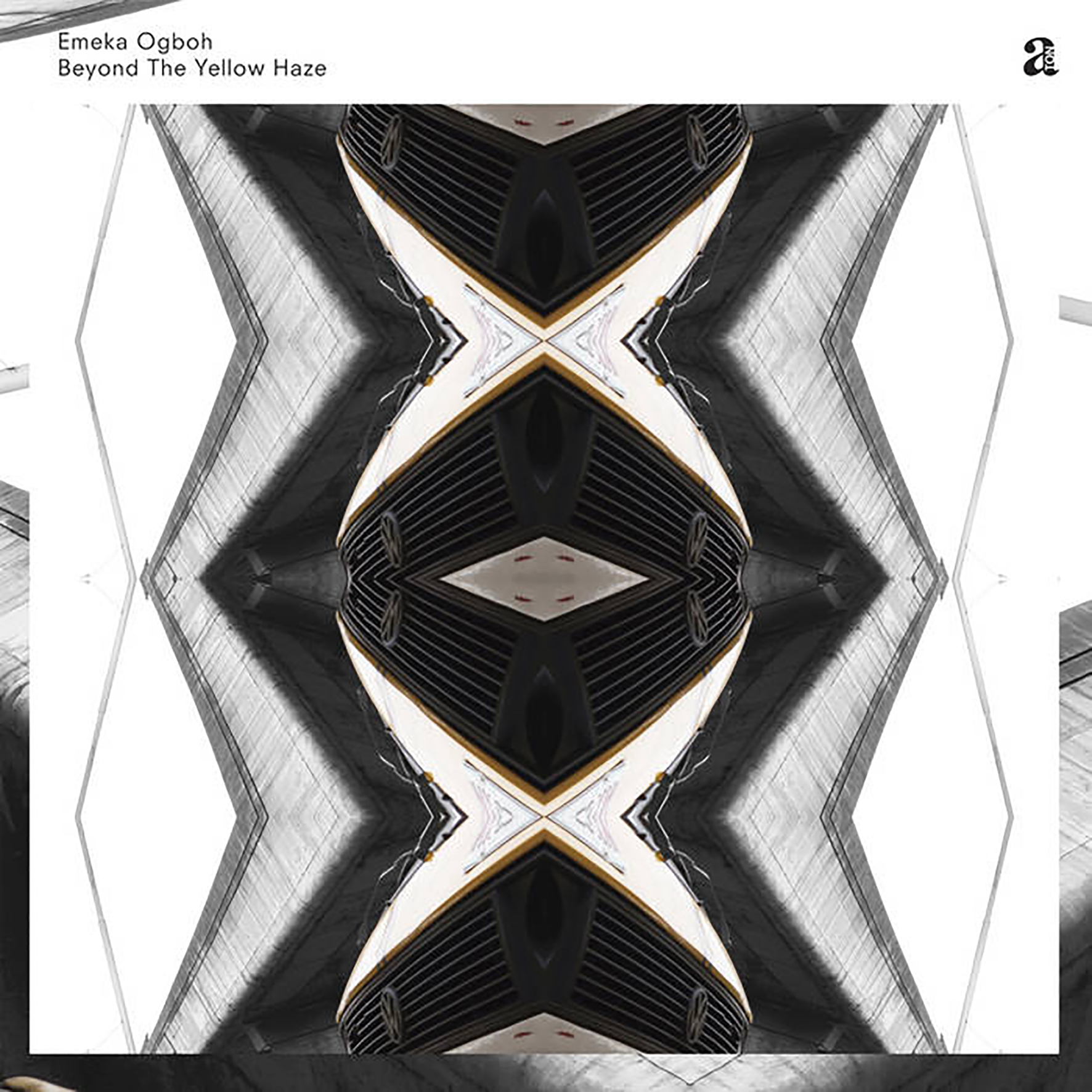

Past experience has taught me not to get too excited about promising-sounding collaborations between great artists, but the allure of this particular project was admittedly damn hard to resist: Body/Head is consistently the most provocative and intense of Sonic Youth's descendants and Aaron Dilloway seems absolutely incapable of releasing a disappointing album these days. Still, there is never any way to predict which threads will assert their dominance when distinctive visions collide, so there are a number of possible shapes that this album could have taken. To my ears, it is Dilloway's broken, murky, and obsessively looping aesthetic that mostly steers the ship, but the balance between the three artists is sufficiently unpredictable and shifting to make this trio feel like something quite different from either Dilloway's solo work or past Body/Head releases. Matt Krefting already did a fine job of summarizing the trio's shared vision with "over and over one gets the sense that the music is trying to wake itself from a dream," but it is also more than that, as this trio have a real knack for slowly transforming gnarled and challenging introductory themes into unexpected passages of sublime beauty. This bombshell release is the first album from Nigerian sound and installation artist Emeka Ogboh, but it sounds like the assured work of killer dub techno producer at the height of their powers. On its surface, Beyond The Yellow Haze admittedly (and probably unintentionally) shares a lot of common ground with prime Muslimgauze, as a central theme of Ogboh's art is his passion for capturing the ambient city sounds of Lagos. Consequently, these five pieces are nicely enhanced with layers of street noise, conversations, and passing snatches of melody, yet Beyond The Yellow Haze is primarily a great album because Ogboh is a goddamn wizard at crafting heavy, shape-shifting grooves with elegant dubwise percussion flourishes. I suppose the beats also creep into Muslimgauze territory at times, as Ogboh is similarly quite fond of slow and hypnotic grooves flavored with African and Arabic rhythms, yet the two artists differ dramatically when it comes to focus and exacting execution (among other things), as nearly every song here is a flawless diamond of immersively layered textures, slow-burning dynamic transformation, and crunching physicality. This is probably the strongest beat-driven album that I have heard all year, debut or otherwise.

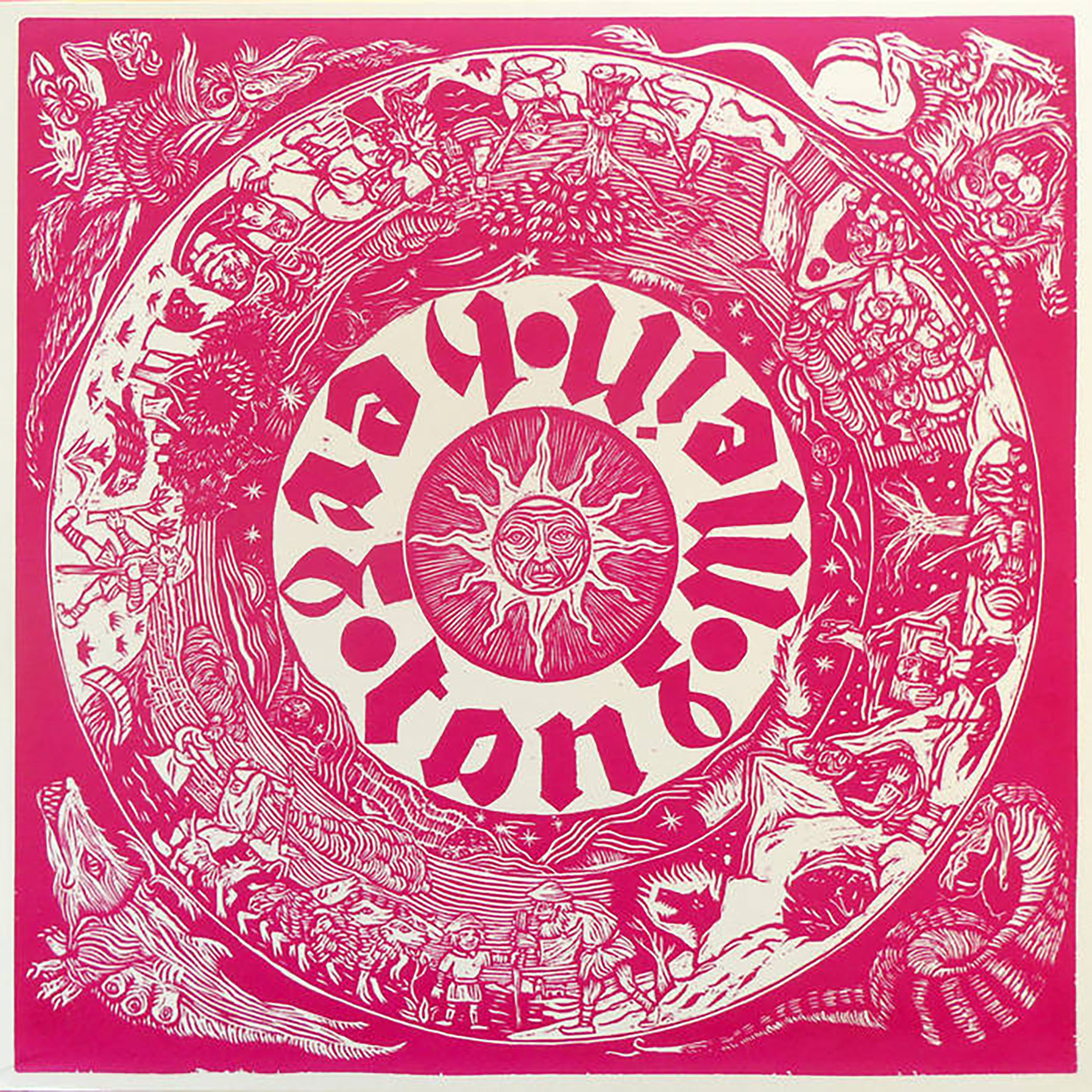

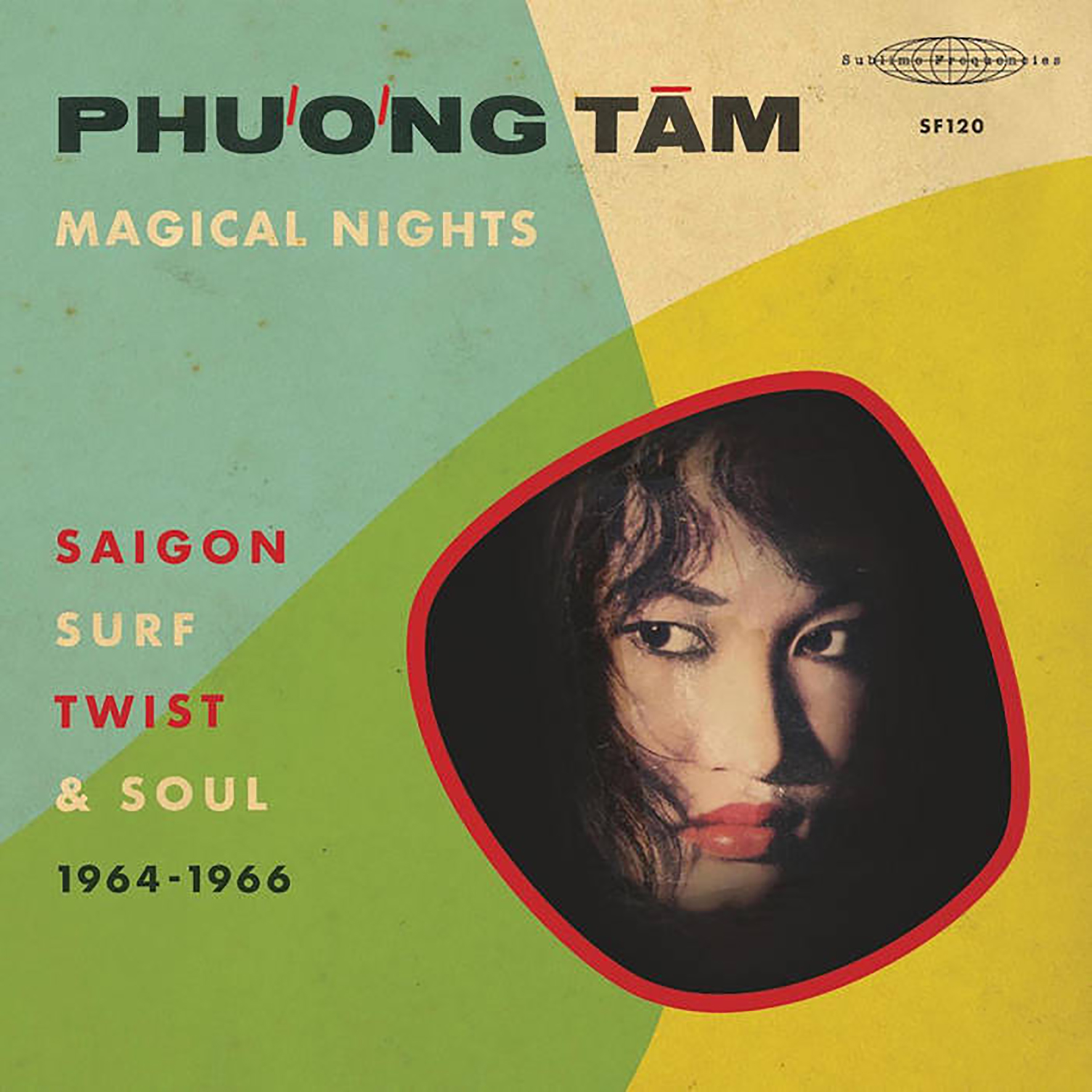

This bombshell release is the first album from Nigerian sound and installation artist Emeka Ogboh, but it sounds like the assured work of killer dub techno producer at the height of their powers. On its surface, Beyond The Yellow Haze admittedly (and probably unintentionally) shares a lot of common ground with prime Muslimgauze, as a central theme of Ogboh's art is his passion for capturing the ambient city sounds of Lagos. Consequently, these five pieces are nicely enhanced with layers of street noise, conversations, and passing snatches of melody, yet Beyond The Yellow Haze is primarily a great album because Ogboh is a goddamn wizard at crafting heavy, shape-shifting grooves with elegant dubwise percussion flourishes. I suppose the beats also creep into Muslimgauze territory at times, as Ogboh is similarly quite fond of slow and hypnotic grooves flavored with African and Arabic rhythms, yet the two artists differ dramatically when it comes to focus and exacting execution (among other things), as nearly every song here is a flawless diamond of immersively layered textures, slow-burning dynamic transformation, and crunching physicality. This is probably the strongest beat-driven album that I have heard all year, debut or otherwise. This collection, which I hereby deem an instant Sublime Frequencies classic, is devoted entirely to the long-unheard and elusive discography of one of the most magnetic singers of Saigon's "golden music" age. Part of the reason why Ph∆∞∆°ng T√¢m's work has languished in undeserved semi-obscurity is grimly predictable, as most of her music was destroyed during Vietnam's great purge of American-influenced culture in 1975, but T√¢m also abruptly ended her singing career in her prime to pursue forbidden love instead (an acceptably cool reason, I feel). According to her daughter Hannah H√†, Phương Tâm remained something of a highly localized karaoke supernova in the years since her stardom days, but H√† did not discover how truly famous her mom actually was until late 2019. One thing led to another and H√† found Mark Gergis after discovering his beloved Saigon Rock and Soul compilation. Gergis and a handful of like-minded crate-digging luminaries then set about tracking down as much of Ph∆∞∆°ng T√¢m's rare and often mistakenly attributed oeuvre as they could find, much of which even T√¢m herself had not heard since the recording sessions. While the journey to this album is undeniably a fascinating and heart-warming one, the best part is the songs themselves, as this album is a treasure trove of fun, soulful, and sexy genre-blurring gems from the golden age of swinging Saigon nightlife. Moreover, I was legitimately gobsmacked to learn that these songs were all recorded by the same person in such a brief span, as T√¢m channels everything from Brenda Lee to Ella Fitzgerald to the kind of impossibly cool, sexy, and ahead-of-their-time numbers that feel like would-be highlights from Lux Interior and Poison Ivy‚Äôs oft-anthologized record collection.

This collection, which I hereby deem an instant Sublime Frequencies classic, is devoted entirely to the long-unheard and elusive discography of one of the most magnetic singers of Saigon's "golden music" age. Part of the reason why Ph∆∞∆°ng T√¢m's work has languished in undeserved semi-obscurity is grimly predictable, as most of her music was destroyed during Vietnam's great purge of American-influenced culture in 1975, but T√¢m also abruptly ended her singing career in her prime to pursue forbidden love instead (an acceptably cool reason, I feel). According to her daughter Hannah H√†, Phương Tâm remained something of a highly localized karaoke supernova in the years since her stardom days, but H√† did not discover how truly famous her mom actually was until late 2019. One thing led to another and H√† found Mark Gergis after discovering his beloved Saigon Rock and Soul compilation. Gergis and a handful of like-minded crate-digging luminaries then set about tracking down as much of Ph∆∞∆°ng T√¢m's rare and often mistakenly attributed oeuvre as they could find, much of which even T√¢m herself had not heard since the recording sessions. While the journey to this album is undeniably a fascinating and heart-warming one, the best part is the songs themselves, as this album is a treasure trove of fun, soulful, and sexy genre-blurring gems from the golden age of swinging Saigon nightlife. Moreover, I was legitimately gobsmacked to learn that these songs were all recorded by the same person in such a brief span, as T√¢m channels everything from Brenda Lee to Ella Fitzgerald to the kind of impossibly cool, sexy, and ahead-of-their-time numbers that feel like would-be highlights from Lux Interior and Poison Ivy‚Äôs oft-anthologized record collection. This unique debut album is definitely one of the year's most pleasant surprises, as art/music journalist Kretowicz assembled a bevy of talented collaborators to craft a poignant and subtly hallucinatory tour de force of autofiction-based sound art. While some of the people involved (Mica Levi, Tirzah, etc.) certainly enhance the initial allure of I hate it here, it is a great challenge to focus on anything other than Kretowicz's sardonic, time-bending narrative as soon as she opens her mouth and things gets rolling. Thematically, the album is billed as a "psychedelic audio narrative" that "wanders through a layered and multi-dimensional notion of existence as suffering," which mostly feels apt, yet it fails to convey how truly charming and blackly funny wandering through that notion with Kretowicz can be. More importantly, this is the rare spoken word album that remains compelling beyond the first listen, as the combination of Kretowicz's deadpan, accented voice and the sound collage talents of felicita & Ben Babbitt make it an absorbing delight long after the meaning and impact of Kretowicz's words dissipate into more abstract and nuanced pleasures like texture and feeling. To my ears, this is one of the most inspired, immersive, and memorable albums of the year.

This unique debut album is definitely one of the year's most pleasant surprises, as art/music journalist Kretowicz assembled a bevy of talented collaborators to craft a poignant and subtly hallucinatory tour de force of autofiction-based sound art. While some of the people involved (Mica Levi, Tirzah, etc.) certainly enhance the initial allure of I hate it here, it is a great challenge to focus on anything other than Kretowicz's sardonic, time-bending narrative as soon as she opens her mouth and things gets rolling. Thematically, the album is billed as a "psychedelic audio narrative" that "wanders through a layered and multi-dimensional notion of existence as suffering," which mostly feels apt, yet it fails to convey how truly charming and blackly funny wandering through that notion with Kretowicz can be. More importantly, this is the rare spoken word album that remains compelling beyond the first listen, as the combination of Kretowicz's deadpan, accented voice and the sound collage talents of felicita & Ben Babbitt make it an absorbing delight long after the meaning and impact of Kretowicz's words dissipate into more abstract and nuanced pleasures like texture and feeling. To my ears, this is one of the most inspired, immersive, and memorable albums of the year. This is one of those rare collaborations in which I had absolutely no idea what kind of album to expect, as the only obvious common ground this duo shares is a strong interest in sound design, though it is probably safe to say they are both drawn to unusual projects too given their past involvement with Rắn Cạp ĐuôI Collective. Now that I have heard Myxomy, however, I am faced with the fresh challenge of describing a vision that is elusively shapeshifting, kaleidoscopic, and wrong-footing from start to finish. I suppose the most consistent aesthetic is something akin to "half-deconstructed/half-maximalist outsider R&B" or some similarly heretofore nonexistent genre, but the real theme seems to exclusively be one of endless mutation. In fact, the idea for the collaboration originally began with James Ginzburg sending Ziúr some beats from his early techno days, which triggered a dueling exchange of raw material reworkings that rapidly escalated and morphed until the "duo's fragmented sketches and scribbles took on new life" that "developed into anxious, hybridized pop jewels." To be fair, Myxomy is admittedly poppier than I ever would have anticipated, but this project is waaaaay too weird, fractured, and unpredictable to ever be mistaken for actual pop (jewels or otherwise). It mostly feels more like a handful of hooks wandering through a collapsed post-industrial landscape in search of a proper home. I am not sure any of them ever quite found one (seems doubtful), but some of these experiments are impressively visceral and unique in their own right (even if they can sometimes be a real challenge to digest).

This is one of those rare collaborations in which I had absolutely no idea what kind of album to expect, as the only obvious common ground this duo shares is a strong interest in sound design, though it is probably safe to say they are both drawn to unusual projects too given their past involvement with Rắn Cạp ĐuôI Collective. Now that I have heard Myxomy, however, I am faced with the fresh challenge of describing a vision that is elusively shapeshifting, kaleidoscopic, and wrong-footing from start to finish. I suppose the most consistent aesthetic is something akin to "half-deconstructed/half-maximalist outsider R&B" or some similarly heretofore nonexistent genre, but the real theme seems to exclusively be one of endless mutation. In fact, the idea for the collaboration originally began with James Ginzburg sending Ziúr some beats from his early techno days, which triggered a dueling exchange of raw material reworkings that rapidly escalated and morphed until the "duo's fragmented sketches and scribbles took on new life" that "developed into anxious, hybridized pop jewels." To be fair, Myxomy is admittedly poppier than I ever would have anticipated, but this project is waaaaay too weird, fractured, and unpredictable to ever be mistaken for actual pop (jewels or otherwise). It mostly feels more like a handful of hooks wandering through a collapsed post-industrial landscape in search of a proper home. I am not sure any of them ever quite found one (seems doubtful), but some of these experiments are impressively visceral and unique in their own right (even if they can sometimes be a real challenge to digest).

Back in the mid-'90s, His Name is Alive and Pale Saints were labelmates on 4AD and a seemingly one-off studio collaboration between Warren Defever and Ian Masters called ESP Summer was born. While that debut album arguably felt like a too-smooth and straightforward blend of the two artists' aesthetics, it did not take long for deeper eccentricities start appearing, as the project soon started varying its name (ESP Neighbor, ESP Continent), omitting crucial information from album credits, and exclusively releasing limited releases on odd formats. Aside from that, they also went on a 25 year hiatus that finally ended with a pair of releases on Osaka, Japan's Onkonomiyaki label in 2020. Both were quite weird (Here is composed of minimal, vocal-free sound collages), but one of them was also quite good and this is that one: originally a 5" lathe cut vinyl release entitled 天国の王国, the EP is now getting a second life with the translated and apt title Kingdom of Heaven. More specifically, this EP is comprised of four very divergent covers of a single song from the 13th Floor Elevators' 1966 debut (and one written by Powell St. John rather than the band, no less). While the original "Kingdom of Heaven" is a perfectly fine song that was not exactly begging for further enhancements, its strong hooks make it a perfect and sturdy melodic center for Masters and Defever's freewheeling dreampop and psych experimentation. Given the project's oft-inscrutable trajectory, Kingdom of Heaven is an unexpectedly focused, memorable, and compelling release.

Back in the mid-'90s, His Name is Alive and Pale Saints were labelmates on 4AD and a seemingly one-off studio collaboration between Warren Defever and Ian Masters called ESP Summer was born. While that debut album arguably felt like a too-smooth and straightforward blend of the two artists' aesthetics, it did not take long for deeper eccentricities start appearing, as the project soon started varying its name (ESP Neighbor, ESP Continent), omitting crucial information from album credits, and exclusively releasing limited releases on odd formats. Aside from that, they also went on a 25 year hiatus that finally ended with a pair of releases on Osaka, Japan's Onkonomiyaki label in 2020. Both were quite weird (Here is composed of minimal, vocal-free sound collages), but one of them was also quite good and this is that one: originally a 5" lathe cut vinyl release entitled 天国の王国, the EP is now getting a second life with the translated and apt title Kingdom of Heaven. More specifically, this EP is comprised of four very divergent covers of a single song from the 13th Floor Elevators' 1966 debut (and one written by Powell St. John rather than the band, no less). While the original "Kingdom of Heaven" is a perfectly fine song that was not exactly begging for further enhancements, its strong hooks make it a perfect and sturdy melodic center for Masters and Defever's freewheeling dreampop and psych experimentation. Given the project's oft-inscrutable trajectory, Kingdom of Heaven is an unexpectedly focused, memorable, and compelling release. This EP is the debut release from an "all-female rock band" from South Portland, Maine who are notable for several reasons. The biggest of those reasons is probably that the band's singer/guitarist is Quinnisa Kinsella Mulkerin (one-third of Big Blood's current incarnation), but the fact that all three band members are 15 years old is certainly significant as well. Neither of those things would matter all that much if this EP was not also quite good, but it is a remarkably assured and delightful dose of very cool and distinctive garage rock. Unsurprisingly, there are a few welcome resemblances to Quinnisa's other band, as she certainly shares some of Colleen Kinsella's vocal gifts and the two groups share a similar fondness for guitar noise and the assimilation of classic country influences. For the most part, however, Florida Man is quite a different entity altogether, eschewing most of Big Blood's weirder psych elements in favor of something considerably more raw, stripped down, punchy, and concise.

This EP is the debut release from an "all-female rock band" from South Portland, Maine who are notable for several reasons. The biggest of those reasons is probably that the band's singer/guitarist is Quinnisa Kinsella Mulkerin (one-third of Big Blood's current incarnation), but the fact that all three band members are 15 years old is certainly significant as well. Neither of those things would matter all that much if this EP was not also quite good, but it is a remarkably assured and delightful dose of very cool and distinctive garage rock. Unsurprisingly, there are a few welcome resemblances to Quinnisa's other band, as she certainly shares some of Colleen Kinsella's vocal gifts and the two groups share a similar fondness for guitar noise and the assimilation of classic country influences. For the most part, however, Florida Man is quite a different entity altogether, eschewing most of Big Blood's weirder psych elements in favor of something considerably more raw, stripped down, punchy, and concise. I was inexplicably late to the party on this wonderful London quartet, as the presence of drummer Valentina Magaletti is almost always a reliable indicator that something compelling is happening and that is especially true of this project. Fortunately, I realized my mistake when I chanced upon their 2019 single "Magician's Success" and its delightfully surreal video, which scratched exactly the same itch as all my favorite Broadcast and Stereolab songs (two acts that Vanishing Twin is probably damned to be compared to forever). While I would admittedly be thrilled if Vanishing Twin simply picked up where those two other brilliant bands left off, their actual influences are considerably more wide-ranging and endlessly mutating (Morricone, Sun Ra, Martin Denny, and Alice Coltrane are just a few of the band's explicit inspirations this time around). That said, the album does kick off with yet another excellent and welcome single in the vein of prime Stereolab (the title piece), yet the foursome also achieve a similar degree of success elsewhere with more disco- and swinging '60s film soundtrack-inspired fare. For the most part, I look to Vanishing Twin primarily for great singles at this point and Ookii Gekkou includes at least three of those, so I consider it a success. The rest of the album occasionally verges on being too smoothly poppy for my taste, but the omnipresent virtuosic rhythm section of Magaletti and bassist Susumu Mukai goes a long way towards keeping the album groovy and fun enough to keep me interested regardless.

I was inexplicably late to the party on this wonderful London quartet, as the presence of drummer Valentina Magaletti is almost always a reliable indicator that something compelling is happening and that is especially true of this project. Fortunately, I realized my mistake when I chanced upon their 2019 single "Magician's Success" and its delightfully surreal video, which scratched exactly the same itch as all my favorite Broadcast and Stereolab songs (two acts that Vanishing Twin is probably damned to be compared to forever). While I would admittedly be thrilled if Vanishing Twin simply picked up where those two other brilliant bands left off, their actual influences are considerably more wide-ranging and endlessly mutating (Morricone, Sun Ra, Martin Denny, and Alice Coltrane are just a few of the band's explicit inspirations this time around). That said, the album does kick off with yet another excellent and welcome single in the vein of prime Stereolab (the title piece), yet the foursome also achieve a similar degree of success elsewhere with more disco- and swinging '60s film soundtrack-inspired fare. For the most part, I look to Vanishing Twin primarily for great singles at this point and Ookii Gekkou includes at least three of those, so I consider it a success. The rest of the album occasionally verges on being too smoothly poppy for my taste, but the omnipresent virtuosic rhythm section of Magaletti and bassist Susumu Mukai goes a long way towards keeping the album groovy and fun enough to keep me interested regardless. I believe I first started to become beguiled with Mary Lattimore's work with the release of 2016's At the Dam, but the following year's Collected Pieces definitely deepened my interest further, as it featured at least two stone-cold instant classics (and the rest of it consistently flirted with similar levels of greatness). While that first collection sets the bar intimidatingly high for this second cassette of unreleased songs, digital-only Bandcamp singles, and other stray pieces, Lattimore tends to be admirably discriminating in what she chooses to release and she has been on a bit of a compositional hot streak over the last couple years. Needless to say, there is plenty to enjoy here. As a whole, this second volume is probably a bit less uniformly strong than its predecessor, but it too contains a few pieces that most Lattimore fans will consider essential. Moreover, a couple of them are not included on the Collected Pieces: 2015‚Äã-‚Äã2020 double LP slated for release in January. As such, only casual Lattimore fans can safely pass up this stand-alone collection, as serious harp-heads will probably not want to deny themselves the pleasures of "Sleeping Deer" and "Princess Nicotine."

I believe I first started to become beguiled with Mary Lattimore's work with the release of 2016's At the Dam, but the following year's Collected Pieces definitely deepened my interest further, as it featured at least two stone-cold instant classics (and the rest of it consistently flirted with similar levels of greatness). While that first collection sets the bar intimidatingly high for this second cassette of unreleased songs, digital-only Bandcamp singles, and other stray pieces, Lattimore tends to be admirably discriminating in what she chooses to release and she has been on a bit of a compositional hot streak over the last couple years. Needless to say, there is plenty to enjoy here. As a whole, this second volume is probably a bit less uniformly strong than its predecessor, but it too contains a few pieces that most Lattimore fans will consider essential. Moreover, a couple of them are not included on the Collected Pieces: 2015‚Äã-‚Äã2020 double LP slated for release in January. As such, only casual Lattimore fans can safely pass up this stand-alone collection, as serious harp-heads will probably not want to deny themselves the pleasures of "Sleeping Deer" and "Princess Nicotine."