-

2025 Readers Poll Vote Round Open!

As promised, 2025 is done. Votes are now being taken. Thanks to all who submitted nominations over the last few weeks. It's time to vote. And thanks again as always for the...

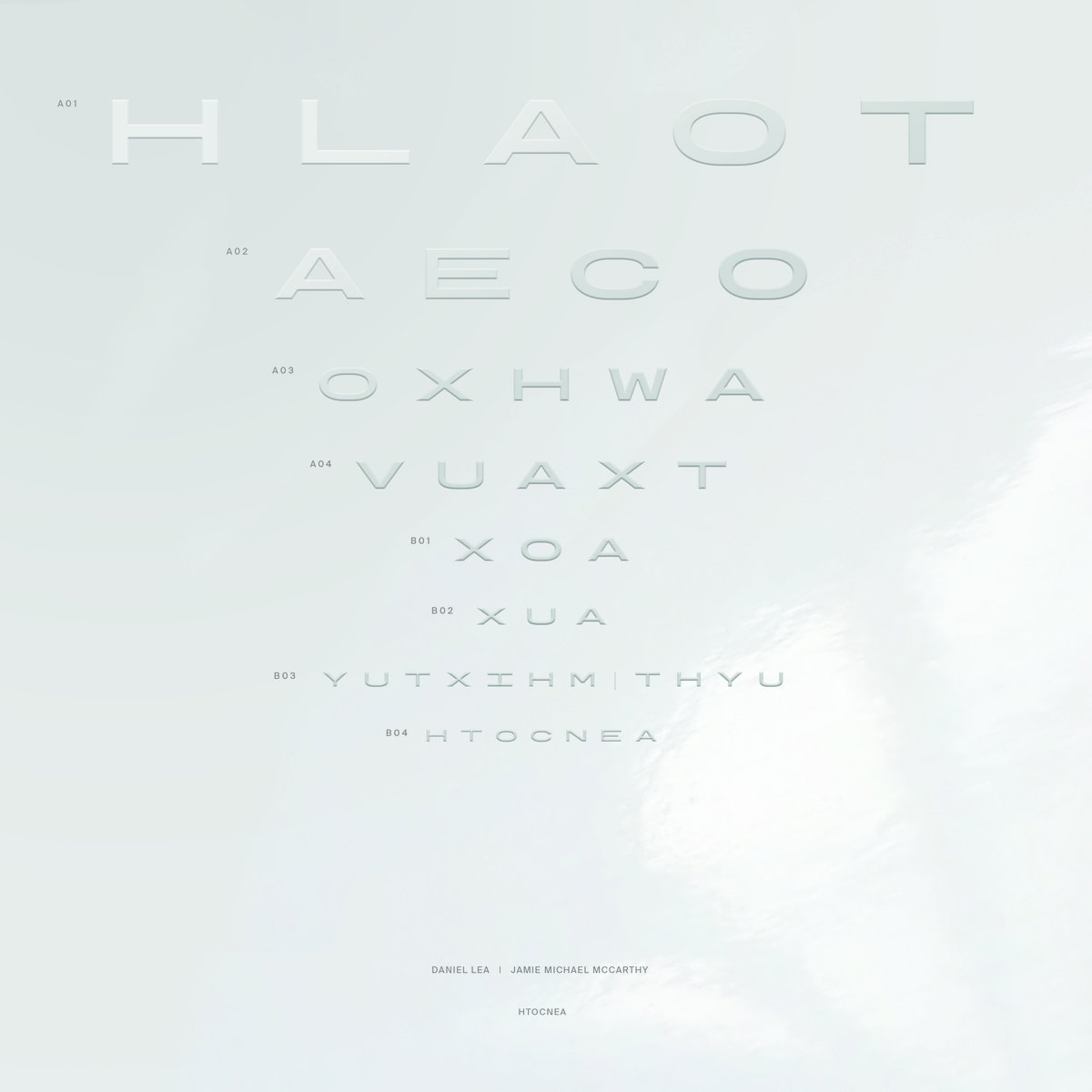

I first encountered Los Angeles-based composer Daniel Lea through L A N D’s excellent Anoxia album back in 2015, but he has become considerably more prolific in recent years after launching his own Vast Habitat imprint. This first collaboration with London-based violinist/cellist Jamie Michael McCarthy has apparently been a decade in the making and borrows both its title and some of its ingenious inspiration from an eye test chart that McCarthy found on the street. On its face, the resultant album has the shapeshifting moods and immersive spell of an art-damaged science fiction score, but immersive headphone listening reveals a considerably deeper and more compelling vision lurking within. Part of that is due to Lea’s considerable sound design talents and inventive assimilation of influences ranging from austere dub techno to avant-garde piano composers and contemporary electronic heavy hitters like Ben Frost and Tim Hecker, but the unusual structural dynamics of these pieces are quite unique and mirror the shifting depth of field that one might get from experimenting with different lenses.

I first encountered Los Angeles-based composer Daniel Lea through L A N D’s excellent Anoxia album back in 2015, but he has become considerably more prolific in recent years after launching his own Vast Habitat imprint. This first collaboration with London-based violinist/cellist Jamie Michael McCarthy has apparently been a decade in the making and borrows both its title and some of its ingenious inspiration from an eye test chart that McCarthy found on the street. On its face, the resultant album has the shapeshifting moods and immersive spell of an art-damaged science fiction score, but immersive headphone listening reveals a considerably deeper and more compelling vision lurking within. Part of that is due to Lea’s considerable sound design talents and inventive assimilation of influences ranging from austere dub techno to avant-garde piano composers and contemporary electronic heavy hitters like Ben Frost and Tim Hecker, but the unusual structural dynamics of these pieces are quite unique and mirror the shifting depth of field that one might get from experimenting with different lenses.

This latest EP from the ever-compelling Diamanda Galás has had quite an interesting journey, as it first began its life in an evolving larger work entitled "Das Fieberspital (The Fever Hospital)," which is a “musical setting of Georg Heym’s early 20th Century expressionist poem about patients stigmatized by yellow fever.” At some point, however, Galás concluded that “the piano skeleton had become its own work” and its (mostly improvised) performance was released as De-formation: Piano Variations back in 2020. Five years later, she was inspired to ambitiously rework that piece for a Paris performance at the Pinault Collection celebrating the legacy of fellow iconoclastic composer Maryanne Amacher. Now in deconstructed, reconstructed, and characteristically volcanic new form, De-formation: Second Piano Variations presents Galás’ “definitive” performance of that visceral tour de force.

This latest EP from the ever-compelling Diamanda Galás has had quite an interesting journey, as it first began its life in an evolving larger work entitled "Das Fieberspital (The Fever Hospital)," which is a “musical setting of Georg Heym’s early 20th Century expressionist poem about patients stigmatized by yellow fever.” At some point, however, Galás concluded that “the piano skeleton had become its own work” and its (mostly improvised) performance was released as De-formation: Piano Variations back in 2020. Five years later, she was inspired to ambitiously rework that piece for a Paris performance at the Pinault Collection celebrating the legacy of fellow iconoclastic composer Maryanne Amacher. Now in deconstructed, reconstructed, and characteristically volcanic new form, De-formation: Second Piano Variations presents Galás’ “definitive” performance of that visceral tour de force. To celebrate the remastered tenth anniversary reissue of his 2015 opus A Fragile Geography, Rafael Anton Irisarri invited an eclectic murderers’ row of his friends and peers to work their transformative magic on his source material. That was a bit of a bold and inspired decision given that the original album is quite bleak and grayscale in nature, but Irisarri’s well-chosen group of reinterpreters found a number of fresh and inventive ways to highlight their most inspired bits or sharpen them into something that beautifully transcends their original inspiration. To my ears, Abul Mogard and Kevin Martin largely steal the show with their killer contributions, but this whole album is a quite a fascinating companion piece to one of Irisarri’s most celebrated albums (and even manages to surpass it on several occasions).

To celebrate the remastered tenth anniversary reissue of his 2015 opus A Fragile Geography, Rafael Anton Irisarri invited an eclectic murderers’ row of his friends and peers to work their transformative magic on his source material. That was a bit of a bold and inspired decision given that the original album is quite bleak and grayscale in nature, but Irisarri’s well-chosen group of reinterpreters found a number of fresh and inventive ways to highlight their most inspired bits or sharpen them into something that beautifully transcends their original inspiration. To my ears, Abul Mogard and Kevin Martin largely steal the show with their killer contributions, but this whole album is a quite a fascinating companion piece to one of Irisarri’s most celebrated albums (and even manages to surpass it on several occasions). I was definitely not expecting a new Tear Garden album this year, but Edward Ka-Spel and cEvin Key’s fitful four-decade collaboration has happily resurfaced once again after an eight-year hiatus. I am tempted to call Astral Elevator a return to the duo’s “classic” sound after the more eclectic and playful The Brown Acid Caveat, but the only real difference is that this latest batch of tightly edited and hook-heavy “singles” has been purged of the more groovy and disco/dance elements found in its predecessor. I suppose that makes Astral Elevator a somewhat darker release, but the world is now a darker place then it was back in 2017 and there are a handful of highlights here that certainly brighten my small part of it.

I was definitely not expecting a new Tear Garden album this year, but Edward Ka-Spel and cEvin Key’s fitful four-decade collaboration has happily resurfaced once again after an eight-year hiatus. I am tempted to call Astral Elevator a return to the duo’s “classic” sound after the more eclectic and playful The Brown Acid Caveat, but the only real difference is that this latest batch of tightly edited and hook-heavy “singles” has been purged of the more groovy and disco/dance elements found in its predecessor. I suppose that makes Astral Elevator a somewhat darker release, but the world is now a darker place then it was back in 2017 and there are a handful of highlights here that certainly brighten my small part of it. This latest release from the New York-based composer saxophonist is a bold and deeply psychedelic departure from her usual terrain (aside from being partially recorded in a cave, of course). The first big surprise is that The Oracle is an extremely vocal-centric album to an almost a capella degree. The other major twist is that Bertucci “creatively misuses a reel-to-to-reel tape machine to live-manipulate her voice” into an unpredictably kaleidoscopic and hallucinatory swirl of bubbling, hissing, murmuring, and slurred words stripped of most context and meaning.

This latest release from the New York-based composer saxophonist is a bold and deeply psychedelic departure from her usual terrain (aside from being partially recorded in a cave, of course). The first big surprise is that The Oracle is an extremely vocal-centric album to an almost a capella degree. The other major twist is that Bertucci “creatively misuses a reel-to-to-reel tape machine to live-manipulate her voice” into an unpredictably kaleidoscopic and hallucinatory swirl of bubbling, hissing, murmuring, and slurred words stripped of most context and meaning.  Fed Up With Bass was somewhat conceived as a pandemic project. During lockdown, legendary improv guitarist Eugene Chadbourne was recording daily-ish solo guitar pieces and sharing them online, while encouraging other artists to utilize them in an asynchronous collaborative setting. Bassist/electronic artist Jair-Röhm Parker Wells, whom Chadbourne had worked with in person previously, was a prolific collaborator, and this sprawling album is a document of these combined performances: a mix of sounds and styles that is as dizzying as it is fascinating.

Fed Up With Bass was somewhat conceived as a pandemic project. During lockdown, legendary improv guitarist Eugene Chadbourne was recording daily-ish solo guitar pieces and sharing them online, while encouraging other artists to utilize them in an asynchronous collaborative setting. Bassist/electronic artist Jair-Röhm Parker Wells, whom Chadbourne had worked with in person previously, was a prolific collaborator, and this sprawling album is a document of these combined performances: a mix of sounds and styles that is as dizzying as it is fascinating. There is not a hell of a lot of background information about this latest installment of the Dots’ long-running Chemical Playschool series other than the fact that it was recorded in 2025 and will eventually have a double vinyl release. Fortunately, anyone who has been following LPD’s career for a while will know exactly what to expect: a deep and eclectic dive into free-form psychedelia, promising song fragments, and wherever the hell else the band feels like throwing into the mix.

There is not a hell of a lot of background information about this latest installment of the Dots’ long-running Chemical Playschool series other than the fact that it was recorded in 2025 and will eventually have a double vinyl release. Fortunately, anyone who has been following LPD’s career for a while will know exactly what to expect: a deep and eclectic dive into free-form psychedelia, promising song fragments, and wherever the hell else the band feels like throwing into the mix. A collaboration between the duo of Ampyre and the varied membership of Death Factory, Death Pyre's Concatenation is one part of a trilogy of albums released in 2025. Sharing elements of multiple electronic styles that lean into more abrasive forms, the three pieces on this tape are wonderfully unpredictable and extremely compelling for that very reason.

A collaboration between the duo of Ampyre and the varied membership of Death Factory, Death Pyre's Concatenation is one part of a trilogy of albums released in 2025. Sharing elements of multiple electronic styles that lean into more abrasive forms, the three pieces on this tape are wonderfully unpredictable and extremely compelling for that very reason. This is the first new release from Emeralds’ former synth wizard in six years and marks a return to his DIY past with the unveiling of his new imprint Simul (much of Hauschildt’s early work was self-released on his own Gneiss Things label). Obviously, a hell of a lot has happened globally since Hauschildt last surfaced, but it seems like a hell of a lot has happened personally for him as well, as he left Chicago to live on the other side of the world in Tbilisi, Georgia.

This is the first new release from Emeralds’ former synth wizard in six years and marks a return to his DIY past with the unveiling of his new imprint Simul (much of Hauschildt’s early work was self-released on his own Gneiss Things label). Obviously, a hell of a lot has happened globally since Hauschildt last surfaced, but it seems like a hell of a lot has happened personally for him as well, as he left Chicago to live on the other side of the world in Tbilisi, Georgia.