- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

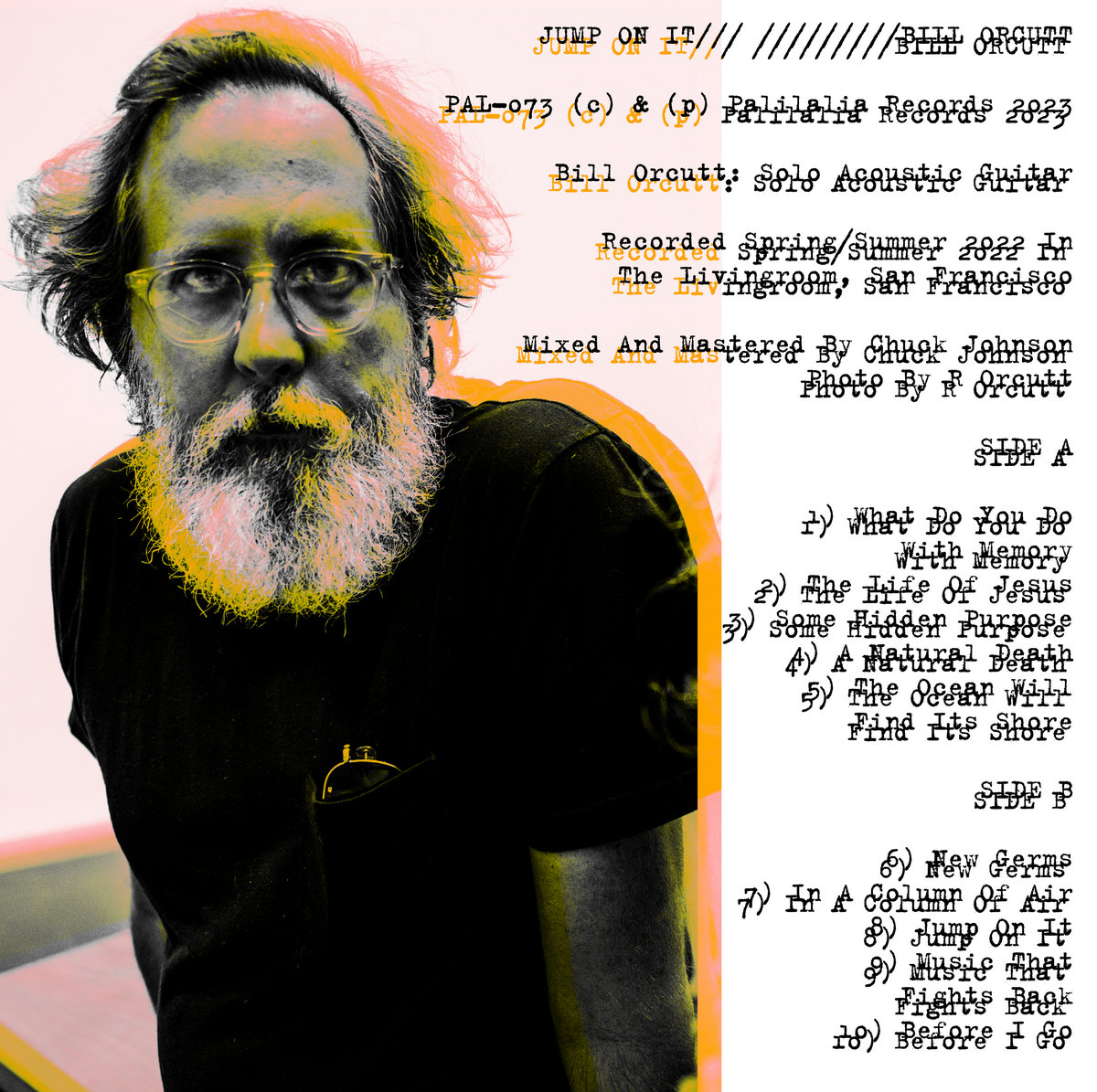

This latest LP from San Francisco-based guitar visionary Bill Orcutt is a spiritual successor of sorts to 2013's A History of Every One, as that was apparently his last solo acoustic guitar album. The resemblance between the two albums largely ends there, however, as Jump On It is as different from the deconstructed standards of History as it is from last week's Chatham-esque guitar quartet performance for NPR. While I do enjoy Orcutt's Editions Mego solo era quite a bit, there is no denying that his artistry has evolved dramatically over the last decade and his recent work definitely connects with me on a deeper level. In more concrete terms, Orcutt's work no longer resembles the choppy, convulsive, and possessed-sounding fare of History, as he has since reined in his more fiery, passionate impulses enough to leave more room for passages of tender, simple beauty. In fact, Jump On It might be the farthest that the balance has swung towards the latter, as the characteristic Orcutt violence is a rare presence in the collection of quietly lovely and spontaneous-sounding guitar miniatures.

This latest LP from San Francisco-based guitar visionary Bill Orcutt is a spiritual successor of sorts to 2013's A History of Every One, as that was apparently his last solo acoustic guitar album. The resemblance between the two albums largely ends there, however, as Jump On It is as different from the deconstructed standards of History as it is from last week's Chatham-esque guitar quartet performance for NPR. While I do enjoy Orcutt's Editions Mego solo era quite a bit, there is no denying that his artistry has evolved dramatically over the last decade and his recent work definitely connects with me on a deeper level. In more concrete terms, Orcutt's work no longer resembles the choppy, convulsive, and possessed-sounding fare of History, as he has since reined in his more fiery, passionate impulses enough to leave more room for passages of tender, simple beauty. In fact, Jump On It might be the farthest that the balance has swung towards the latter, as the characteristic Orcutt violence is a rare presence in the collection of quietly lovely and spontaneous-sounding guitar miniatures.

The album opens in appropriately gorgeous fashion, as the first minute of "What Do You Do With Memory" is devoted to a tender, halting and bittersweet arpeggio motif, though the piece then takes a detour before reprising that wonderful theme for the finale. The detour is admittedly brief, but so is the song itself, which illustrates a central feature of this album: these pieces generally feel like a series of spontaneous snapshots/3-minute vignettes rather than fully formed compositions that build into something more. That is not meant as a critique, but it does mean that Jump On It is something other than Orcutt's next major artistic statement. I am tempted to say that most of this album feels akin to a pleasant but loose improvisation around a campfire, but there are also some pieces that evoke an usually meditative Django Reinhardt playing alone in a late-night hotel room.

The connective tissue between those two poles is, of course, casual virtuosity and that is the most readily apparent trait of Jump On It: it can feel languorous, pensive, and searching at times, but there are plenty of fiery runs, viscerally snapping bends, and surges of passion to keep things compelling and remind me that this is still very much a Bill Orcutt album. To my ears, "The Ocean Will Find Its Shore" is the album's centerpiece, as its early sense of forward motion seamlessly dissipates into a tender reverie before more intense emotions bubble to the surface for a brief but intense crescendo. "In A Column Of Air" is another major highlight, however, as a lyrical minor key melody fitfully winds through scrabbling note flurries, quivering double-stops, emphatic chord sweeps, violent bends, and sundry other dynamic flourishes (and it all ends with a killer repeating riff to boot). Unsurprisingly, the remaining pieces are all enjoyable as well, albeit with the caveat that they generally feel more like sketches or miniatures than fresh, fully articulated masterpieces.

While I still heartily maintain that just about everything released on Orcutt's main Palilalia imprint is compelling and significant, I am quite curious to see how this album in particular is received. It feels like one of his less substantial recent releases to me (particularly in the wake of Music For Four Guitars), yet it also seems like it could reach an atypically wide audience, as Orcutt's characteristically soulful and singular playing is couched in a much more casual and intimate setting than the snarling, incendiary, and more overtly avant-garde fare that he is usually associated with.

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

Finally seeing the light of day after two years of production related delays, with the recordings dating back even longer than that, this collaboration between Daniel Burke (IOS) and the late Stefan Weisser (Z'EV) could almost be a time capsule, except the sound of it is entirely timeless. Recorded and mixed between 2008 and 2012, the two lengthy pieces that make up this self-titled album clearly bear the mark of both individuals, but mesh together beautifully in the very different sounding sides of the record.

Finally seeing the light of day after two years of production related delays, with the recordings dating back even longer than that, this collaboration between Daniel Burke (IOS) and the late Stefan Weisser (Z'EV) could almost be a time capsule, except the sound of it is entirely timeless. Recorded and mixed between 2008 and 2012, the two lengthy pieces that make up this self-titled album clearly bear the mark of both individuals, but mesh together beautifully in the very different sounding sides of the record.

Feast of Hate and Fear / Cipher Productions / Oxidation / Korm Plastics / Drone / Personal Archives / Public Eyesore / Tribe Tapes / Liquid Death / No Part of It

Although a mail-based collaboration, Z'EV and IOS's work complement each other perfectly, with the acoustic percussion from the former weaved into the electronics and field recordings of the latter, and both artists having a hand in further mixing and processing afterwards. These elements are clear on both side-long pieces that make up the album, but structurally the two halves differ rather notably.

The first piece, "A Strategy of Transformation," is the more chaotic of the two. Jerky stop/starts, abrupt percussive outbursts, and oddly processed field recordings constantly flow and keep things moving, albeit in a extremely unpredictable way. Disorienting in its structure, the piece drastically swings from violent metallic clattering to subtle synth tones and into processed field recordings. Harsh, pummeling layers of noise are quickly pulled back to leave only open space before blasting off again. At the end some of the few clearly discernable sounds come in, mostly the plucked strings of a guitar (I assume) and banging metal, but the most of what precedes that is pure ambiguity.

The other side, "Smaller Revolutions," features the two working instead with sustained, elongated structures as opposed to the chaos of the other half. Bright electronic tones underscore metallic percussion bathed in heavy reverb. Electronics tend to stay consistent, with other layers brought in and out, although less abruptly than the other side. Fragments of conversation, what could be the rhythmic clattering of a train, and the sounds of birds all appear. It might be comparably more structured, but it equally as challenging as the first half.

Apparently, this is only a portion of the recordings Burke and Weisser exchanged, so I would imagine more work is likely forthcoming. But even with just this record, the two have produced a work that balances complexity and harshness extremely well. Never full on brutal, nor purely ambient, but drifts nicely between those two extremities, and the differing structures kept it a fascinating work from the beginning all the way to the end.

Read More

- Creaig Dunton

- Albums and Singles

A 10" record rigidly divided into four different pieces (each mostly around four minutes in length), this new work from the enigmatic sounding, long-standing UK project is mostly centered around the same authoritarian lyrical elements, but each differs significantly in their compositional approach. A complex mix of styles define each piece, neither of which are too similar to another, but are unquestionably Contrastate, and showcases all of the unique sounds they are known for.

A 10" record rigidly divided into four different pieces (each mostly around four minutes in length), this new work from the enigmatic sounding, long-standing UK project is mostly centered around the same authoritarian lyrical elements, but each differs significantly in their compositional approach. A complex mix of styles define each piece, neither of which are too similar to another, but are unquestionably Contrastate, and showcases all of the unique sounds they are known for.

The aforementioned lyrical elements are quite dystopian "You do not have the right to be free/ you do not have the right to shelter and food/You do not have the right to love/You do not have the right to work" are just a few examples and appear in various stages of processing throughout. The first of the four untitled pieces is classic Contrastate: bursts of noise, sustained digital sounds, fragments of voice, and a significant number of loops layered atop one another. Lush synth passages and bits of conversation are consistent with the trio's previous works. For the second, the use of loops continues, but with hints of melody and cut up percussion pervade, making for a more spacious and restrained feel in comparison.

On the other side, Contrastate introduces third piece with deep, pulsating electronics, melodic loops, and subtle metallic percussion, with the band going even more into ambient realms when compared to the first half. For the final song, things get almost normal sounding. The same voice samples appear but here they're cut up and processed more and make for part of a low bit rate digital mass. Everything else builds to an almost techno throb via complex drum programming that could almost be danceable. Towards the end the piece makes another shift, this time into a jazzy shuffle that's even further "out there" for the band.

The totalitarian themed voices that appear in all four of the songs on 35 Project could end up a bad cliché in the wrong hands, but the occasional bleak humor that appears throughout Contrastate's discography makes this far less of a liability and instead consistent with what I would expect. Almost like a stylistic sampler of their lengthy discography, there is a lot to be heard in the terse 16 minutes of this EP, and all of it is wonderful. It is yet another excellent work from a consistently unpredictable project.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This eleventh album from Germany's Kammerflimmer Kollektief is not my first exposure to the project, but it did succeed in making me wonder why I have not been a passionate fan of their work before now. Admittedly, the idea of harmonium-driven free-form jazz/psychedelia is not quite my cup of tea on paper, which goes a long way towards explaining why I was so slow to embrace this project, yet the right execution can transform just about anything into gold and this foursome are extremely good at what they do. It also does not hurt that the Kammerflimmer gang have some intriguing and unusual inspirations, as they namecheck both Franz Mesmer and underheard German psychonauts The Cocoon in addition to the requisite nod to Can. Kammerflimmer Kollektief certainly assimilate those influences in a unique way though, as the best songs on Schemen sound like a killer post-rock/psych band blessed with an unusually great rhythm section and real talents for roiling guitar noise, simmering tension, and volcanic catharsis.

This eleventh album from Germany's Kammerflimmer Kollektief is not my first exposure to the project, but it did succeed in making me wonder why I have not been a passionate fan of their work before now. Admittedly, the idea of harmonium-driven free-form jazz/psychedelia is not quite my cup of tea on paper, which goes a long way towards explaining why I was so slow to embrace this project, yet the right execution can transform just about anything into gold and this foursome are extremely good at what they do. It also does not hurt that the Kammerflimmer gang have some intriguing and unusual inspirations, as they namecheck both Franz Mesmer and underheard German psychonauts The Cocoon in addition to the requisite nod to Can. Kammerflimmer Kollektief certainly assimilate those influences in a unique way though, as the best songs on Schemen sound like a killer post-rock/psych band blessed with an unusually great rhythm section and real talents for roiling guitar noise, simmering tension, and volcanic catharsis.

This unique and eclectic project was founded by guitarist Thomas Weber back in the late '90s and has had a somewhat fluid membership since, but it is safe to say Heike Aumüller significantly transformed its trajectory when she joined the fold in 2002, as she is responsible for both the band's unusual cover art and the even more unusual use of harmonium. Unsurprisingly, I encounter the harmonium a lot with drone music, as it lends itself to that aesthetic perfectly, but Aumüller generally uses it for more melodic purposes and clearly has no aversion to dissonance, as it sounds like she is beating her bandmates to death with an accordion in "Zweites Kapitel [ruckartig]" and "Fünftes Kapitel [kreuzweis]." While "Zweites Kapitel" is an endearingly explosive feast of scrabbling guitar noise, clattering free-form drumming, and tormented bow scrapes, the album's stronger pieces tend to be those which take a more simmering and sensuous approach.

The two major highlights are arguably "Drittes Kapitel [ungesagt, dann vergessen]" and "Sechstes Kapitel [herausgewunden]." In the former, a soulful slide guitar melody unfolds over an understated and almost sultry drum and double bass backdrop before unexpectedly exploding into a viscerally howling noise-guitar catharsis around the halfway point. In the latter, Weber's guitar sleepily slides around over a gently smoldering groove before drummer Christopher Brunner unleashes one hell of a free drumming tour de force. I suppose my praise of those two pieces suggests that Kammerflimmer Kollektief invariably propel themselves towards the expected free music freakout, but the reality is happily more compelling and sophisticated than that, as there are often some delightful psychotropic textures and vapor trails involved, as well as an effortlessly organic "hive mind" intuition for waxing and waning intensity. Aumüller's harmonium also adds an element of temporal dislocation to the mix, as its presence often feels beamed in from a previous century. The album's remaining pieces generally tend to be either too brief or too deconstructed to make the same deep impact as the highlights, but the shapeshifting opener "Erstes Kapitel [verschliffen]" certainly has some memorably trippy and intense moments and everything adds up to an impressively strong and distinctive whole. It is quite nice to hear musicians with legitimate jazz chops devoted to such a noisy, spacey, and psych-damaged vision.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

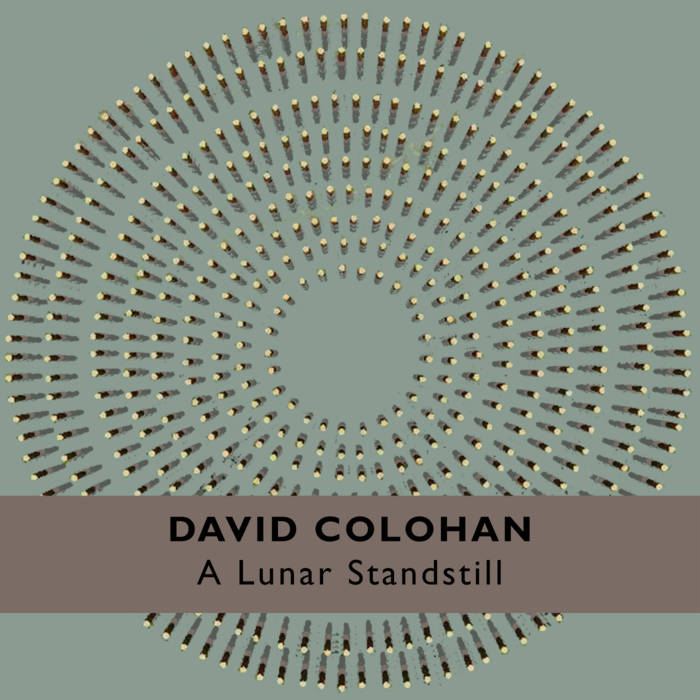

In the village of Stanton Drew, and dating from around 4,500 years ago, is the third largest complex of standing stone circles in England. David Colohan visited the site one rainy morning in early 2020 and was inspired by the mix of winter sunshine and eerie ancient atmosphere to create a record of his impressions. Fair enough, since people rarely send postcards from their travels anymore. Actually, the postcard analogy only works if it allows for someone designing a postcard when they get home, since Colohan's use of field recordings is minimal and he doesn't really create music in situ. He's done this before with other locations but A Lunar Standstill is easily his most consistent recording.

In the village of Stanton Drew, and dating from around 4,500 years ago, is the third largest complex of standing stone circles in England. David Colohan visited the site one rainy morning in early 2020 and was inspired by the mix of winter sunshine and eerie ancient atmosphere to create a record of his impressions. Fair enough, since people rarely send postcards from their travels anymore. Actually, the postcard analogy only works if it allows for someone designing a postcard when they get home, since Colohan's use of field recordings is minimal and he doesn't really create music in situ. He's done this before with other locations but A Lunar Standstill is easily his most consistent recording.

Colohan uses alto saxophone, clarinet, electric guitar, field recordings, harmonium, mellotron, modular synthesizer, trombone, and voice. Maybe I am triggered in a good way by the harmonium but much of this music gives off such a warm and pleasant hum that I started dreaming about Ivor Cutler as a Druid—although I hope that does not sound trite, as Cutler's music has a spiritual grace and trusty home grown solemnity which bestows upon it a uniquely absurd sense of substance and sincerity. The more bizarre it gets the more serious it becomes. On the subject of bizarre, Colohan's "A Static Field" is strange—as if it were composed for divining sticks, ley lines, and glow worms.

This album starts slowly though, with the first couple of tracks seeming like elbows inching into hot water before giving the baby a proper bath, or even someone in a Zen state testing the acoustics in their tiled hallway. It's as if we're driving to the ancient stone circle but we're not there yet. After that things go up a notch: we've arrived, the weather is perfect, and the sandwiches we packed taste unusually good. The voices on "Born Over Blind Springs" seem a portal to elsewhere, to a location where human emotion intersects with history and myth, nature and spirituality. Even better is "The River Talking In It's Sleep," perhaps the most avant-piece here, suitably liquid in structure and flow—with lovely clarinet and mellotron or synth—a real golden ear point climax on the record

The Stanton Drew circles were probably first noted by the famous antiquarian John Aubrey in 1664. He recorded that the villagers were breaking stones with sledge-hammers and that several stones had recently been removed. The circles are less well known and visited than Avebury or Stonehenge, and are situated a few miles southwest of Keynsham (the town culturally immortalized in the title of an album by the Bonzo Dog Band, in reference to Horace Batchelor, a football pools predictor from Keynsham who regularly advertised his service on pop music radio broadcasts in the early 1960s. In advertisements Batchelor would spell out the town's name when reading his postal address. The album starts with a line taken from Batchelor's radio advertisement "I have personally won over..."

David Colohan has been quite prolific, and has releases available for free download. At the risk of sounding like Horace Bachelor, I have personally grabbed several and A Lunar Standstill ranks with my favorite of his works, including "Emmadorp" from Prosperpolder and also his Visitations album. It includes "The Quoit & The Cove" which has an impressive harmonic resonance, even after I realized my wife was inadvertently accompanying David Colohan on vacuum cleaner from the next room.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest release from husband and wife duo Zach & Denny Corsa appears to be their fifth full-length under the Nonconnah name (the duo were previously known as Lost Trail) and it is characteristically wonderful. As is the norm for Nonconnah, Unicorn Family was culled from several years of recordings featuring a host of eclectic collaborators (folks from Lilys, Half Japanese, Fire-Toolz, etc.) and those recordings have been expertly stitched together into beautifully layered and evocative soundscapes teeming with cool tape effects, thought-provoking samples, and killer shoegaze-inspired guitar work. In short, business as usual, but Nonconnah's business is consistently being one of the greatest drone projects on earth, so this is already a lock for one of my favorite albums of the year. Aside from the presence of a lovely lo-fi folk gem with actual singing, the only other notable departures from Nonconnah's existing run of gorgeous albums are shorter song durations than usual and the fact that the duo's samples have more of an eschatological bent. I suppose this album is an unusually focused and distilled statement as well, but that feels like a lateral move given how much I loved the sprawling immensity of Don't Go Down To Lonesome Holler.

This latest release from husband and wife duo Zach & Denny Corsa appears to be their fifth full-length under the Nonconnah name (the duo were previously known as Lost Trail) and it is characteristically wonderful. As is the norm for Nonconnah, Unicorn Family was culled from several years of recordings featuring a host of eclectic collaborators (folks from Lilys, Half Japanese, Fire-Toolz, etc.) and those recordings have been expertly stitched together into beautifully layered and evocative soundscapes teeming with cool tape effects, thought-provoking samples, and killer shoegaze-inspired guitar work. In short, business as usual, but Nonconnah's business is consistently being one of the greatest drone projects on earth, so this is already a lock for one of my favorite albums of the year. Aside from the presence of a lovely lo-fi folk gem with actual singing, the only other notable departures from Nonconnah's existing run of gorgeous albums are shorter song durations than usual and the fact that the duo's samples have more of an eschatological bent. I suppose this album is an unusually focused and distilled statement as well, but that feels like a lateral move given how much I loved the sprawling immensity of Don't Go Down To Lonesome Holler.

The album opens on an unusually simple and intimate note with "It's Eschatology! The Musical," which approximates a melancholy Microphones-esque strain of indie folk recorded directly to boombox. Despite its amusing title and throwaway final line of "that's how the album starts," it is a legitimately lovely, soulful, and direct way to kick off an album that is otherwise composed entirely of complexly layered soundscapes of tape loops and shimmering guitar noise. I have been an enthusiastic fan of those soundscapes for a while, of course, as well as an equally huge fan of the way the pair transform sped-up tape loops into rapturously dizzying and swirling mini-symphonies at the heart of their drone pieces. Given that, I do not have anything particularly fresh to say on those topics other than that I was newly struck by how the combination of slow drones and sped up tapes evokes the hypnotic streaking of car lights in time-lapse footage of a busy highway at night.

I was also newly struck by how singularly Nonconnah succeed at making ambient/drone music feel deeply personal and sometimes even profound. I have had similar thoughts about Celer in the past, but Nonconnah achieve the same feat in a much more direct way, as Zach and Denny often embed compelling monologues in their pieces that reveal a bit of their inner lives and existential preoccupations. In the case of this album, those monologues tend to be about religious experiences, how chance encounters with other people can completely change our lives, and how revelatory it can be when one's perspective regarding one's place in the universe is transformed. In fact, it often feels like great Nonconnah songs exist solely to frame a fleeting glimpse of deep wisdom for maximum impact. While those moments might feel like standard self-help or religious fare in a different context, their apocalyptic context here feels more like a dear friend just time-traveled back and grabbed me by the shoulders to impart something incredibly urgent and potentially life-changing.

That is especially fascinating to me as a non-religious person, as I normally process visions of God and tales of the coming Rapture with a mixture of skepticism and morbid humor, but a piece like "And It Was Beautiful And Glorious" still managed to feel like a religious experience to me, as the central monologue is so movingly sincere and hopeful and surrounded by celestial shimmer. The choral samples at the core of "Heaven Becomes Apeirophobia" also stirred similarly euphoric feelings in my dark heart. In the interest of thoroughness, I should probably also mention that "A Small Wave Of Missing Pets In The Early 1980s" is yet another swoon-inducing highlight and that "We Found A Kitten Skull Painted Gold" is darkly mesmerizing, but this whole album is absolutely sublime and feels like the best kind of fever dream. I will be filing Unicorn Family right next to Nate Scheible's Fairfax on my "Albums That Are Sometimes So Profoundly Beautiful That I Feel Like I Imagined Them" shelf.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This latest opus from Tim Hecker is amusingly billed as "a beacon of unease against the deluge of false positive corporate ambient." Given the weighty themes of his previous albums, Hecker's actual inspiration presumably runs much deeper than that, yet the "beacon of unease" part of that claim may be more literal than it sounds, as one of the album's central features is described as "Morse code pulse programming." While I am not well-versed enough in Morse code to determine if Hecker's oddly timed rhythms are covertly incorporating text or a narrative into these warped and nightmarish soundscapes, the gnarled and harrowing melodies that accompany those erratic pulses are more than enough to make the album thoroughly compelling listening regardless. Aside from that, No Highs marks yet another significant creative breakthrough for a formidable artist hellbent on continual reinvention and bold evolution. While it is hard to predict whether or not No Highs will someday be considered one of Hecker's defining masterpieces or merely an admirable and unique detour, its handful of set pieces feel quite brilliant to me and I do not expect my feelings to change on that point..

This latest opus from Tim Hecker is amusingly billed as "a beacon of unease against the deluge of false positive corporate ambient." Given the weighty themes of his previous albums, Hecker's actual inspiration presumably runs much deeper than that, yet the "beacon of unease" part of that claim may be more literal than it sounds, as one of the album's central features is described as "Morse code pulse programming." While I am not well-versed enough in Morse code to determine if Hecker's oddly timed rhythms are covertly incorporating text or a narrative into these warped and nightmarish soundscapes, the gnarled and harrowing melodies that accompany those erratic pulses are more than enough to make the album thoroughly compelling listening regardless. Aside from that, No Highs marks yet another significant creative breakthrough for a formidable artist hellbent on continual reinvention and bold evolution. While it is hard to predict whether or not No Highs will someday be considered one of Hecker's defining masterpieces or merely an admirable and unique detour, its handful of set pieces feel quite brilliant to me and I do not expect my feelings to change on that point..

The general tone of No Highs feels like a continuation of the smeared, howling anguish of Konoyo and Anoyo, approximating lonely distress signals emitted from the smoldering ruins of Konoyo's planetary death spasms. Compositionally, however, No Highs feels like an entirely different animal altogether, as Hecker has swapped out roiling maximalism for simmering minimalism and distilled his palette to little more than insistently telegraph-like synth pings punctuated with occasional plunges into swirling and howling cosmic horror. In fact, the album makes me feel like I am stationed at a desolate outpost in a blackened wasteland nervously watching apocalyptic storms mass on the distant horizon. Unsurprisingly, the strongest pieces tend to be the ones where those storms reach their full fury, such as the opening "Monotony."

Like many pieces on the album, "Monotony" begins modestly with an insistently pinging synth rhythm, but that calm proves to be illusory as one hell of a howling maelstrom stealthily forms to propel the piece towards a thoroughly harrowing and gnarled climax. I am especially impressed at how thoroughly Hecker smears and warps his sounds, as they continually feel like they are fading in and out of focus (and in and out of tune) to create organically shapeshifting (and oft-ugly) harmonies and an immersively spatialized listening experience. To my ears, No Highs often evokes a nightmarish (and more visceral) inversion of Boards of Canada's sun-dappled and nostalgia-soaked "worn and wobbly tape" aesthetic.

The longest pieces tend to be the strongest as well, as lead single "Lotus Light" blossoms into yet another tour de force of smeared and undulating horror, while "Anxiety" culminates in a roiling shoegaze/dreampop finale with some help from recurring guest saxophonist Colin Stetson. I did not expect to be so excited about Tim Hecker enlisting a saxophonist, but his instincts turned out to be characteristically unerring in that regard, as Stetson's infrequent surfacings are a reliable highlight. There are a few other pleasant surprises lurking elsewhere, such as pedal steel flourishes, buried techno grooves, or fluttering Terry Riley-style sax patterns, but they are essentially just icing on an already wonderful cake (cutting edge sound design, inventively frayed and sickly textures, haunting melodies galore, etc.). While there are admittedly a few elements that make No Highs a bit less instantly gratifying than some previous Hecker classics, his absolute mastery of space, tension, texture, and catharsis is truly mesmerizing.

I can think of few artists who have managed to keep such an extended hot streak going and even fewer who potentially re-shape the future of electronic composition with each fresh statement. Tim Hecker may be two decades deep into his career at this point, yet each new album still feels like a legitimate event.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

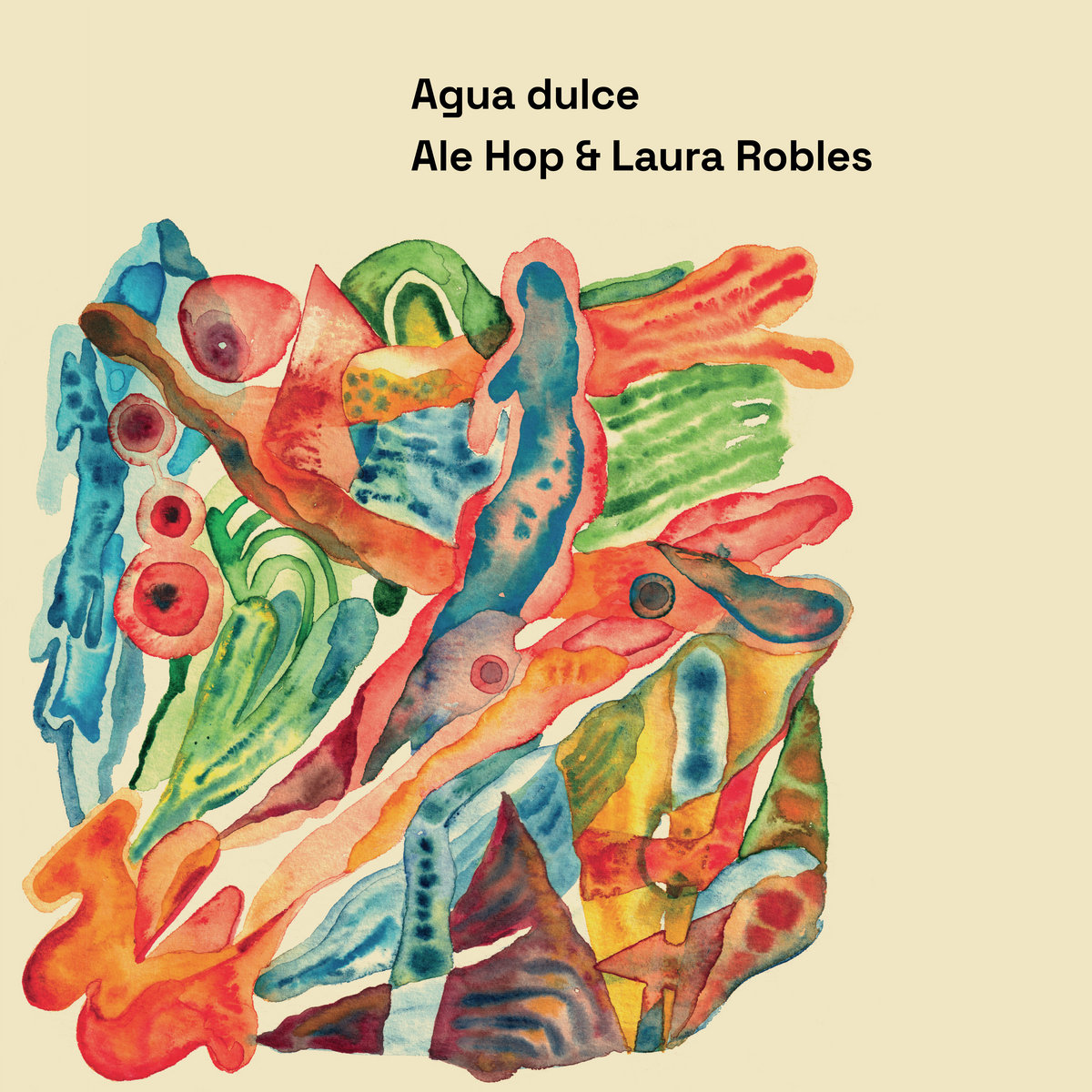

This is the debut collaboration between two Berlin-based Peruvian musicians and also marks my first exposure to percussionist Laura Robles. I am, however, reasonably familiar with the alien soundscapes of Ale Hop (Alejandra Cárdenas) and this union seems to have inspired some of her finest work to date. Notably, Robles is "reputed to be one of the best cajón players in Peru," which is useful context given how radically (yet lovingly) the pair deconstruct and reinvigorate the instrument ("a symbol of resistance, experimentation and transformation" in Peru). In more practical terms, that means that Cárdenas and Robles dramatically disrupt, distort, and repurpose traditional dance rhythms into a wild psychotropic mindfuck. In fact, it sometimes sounds like Robles recorded her parts alone as a freeform performance at an Ayahuasca ceremony or something, but the seemingly roving and divergent threads always come together in impressive fashion in the end. Amusingly, I would have thought that the enigmatically and erratically shifting rhythms of Agua dolce would be damn near impossible to dance to, yet these pieces apparently made quite a splash when the duo coupled with dancer/choreographer Liza Alpiźar Aguilar for the Heroines Of Sound festival. Whether or not that means that I would be a terrible choreographer is hard to say, however, as the finished album may have ultimately landed in far more lysergic territory due to Cárdenas' additional edits and production wizardry.

This is the debut collaboration between two Berlin-based Peruvian musicians and also marks my first exposure to percussionist Laura Robles. I am, however, reasonably familiar with the alien soundscapes of Ale Hop (Alejandra Cárdenas) and this union seems to have inspired some of her finest work to date. Notably, Robles is "reputed to be one of the best cajón players in Peru," which is useful context given how radically (yet lovingly) the pair deconstruct and reinvigorate the instrument ("a symbol of resistance, experimentation and transformation" in Peru). In more practical terms, that means that Cárdenas and Robles dramatically disrupt, distort, and repurpose traditional dance rhythms into a wild psychotropic mindfuck. In fact, it sometimes sounds like Robles recorded her parts alone as a freeform performance at an Ayahuasca ceremony or something, but the seemingly roving and divergent threads always come together in impressive fashion in the end. Amusingly, I would have thought that the enigmatically and erratically shifting rhythms of Agua dolce would be damn near impossible to dance to, yet these pieces apparently made quite a splash when the duo coupled with dancer/choreographer Liza Alpiźar Aguilar for the Heroines Of Sound festival. Whether or not that means that I would be a terrible choreographer is hard to say, however, as the finished album may have ultimately landed in far more lysergic territory due to Cárdenas' additional edits and production wizardry.

The album borrows its title from "the most popular beach in Lima," which is near where "both artists lived during their childhood, houses apart, without ever meeting one another." Improbably, they eventually met as expats on the other side of the world and happily found themselves to be kindred spirits tuned into the same outré wavelength. I suppose Robles is arguably the more conventional of the two despite playing Peruvian music in Germany on a self-built electric cajón, but that is only because Ale Hop often sounds like she is from a completely different planet or dimension altogether. The most impressive example of that otherworldliness comes at the midpoint of "Lamento," as the hissing, blatting electronics and sleepy Latin rhythms seem like they are suddenly interrupted by the appearance of ghost UFO that propels the proceedings into dazzling new heights of haunting, spacialized phantasmagoria. That said, the entire first half of the album is one mesmerizing psychotropic jungle freakout after another, as Cárdenas unleashes her inner tropical Lovecraft to conjure a host of squirming, gelatinous, seething, buzzing, and jabbering electronic sounds over Robles' clattering percussion workouts.

I am also quite fond of the more simmering and sensuous closer "Calato," but this whole album feels like a vivid extradimensional jungle nightmare taking place inside a pinball machine. The one caveat is that the improvisatory roots of these pieces occasionally mean that it takes a little while for all the pieces to fall into place, but expectantly waiting for that unpredictably organic convergence to hit only enhances my appreciation for the pair's spontaneous and freewheeling deep psych vision.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This is my first exposure to this UK-based collective centered around Gavin Miller (worriedaboutsatan) and Sophie Green (formerly of Her Name is Calla), but they have been fitfully releasing albums for more than a decade now. Their last major release, Scavengers, was back in 2016 on Time-Released Sound, so Eyes Like Pools both ends a lengthy hiatus and marks the collective’s first appearance on Athens’ sound in silence label. Much like Miller’s worriedaboutsatan project, this latest statement from Marta Mist occupies a vaguely cinematic stylistic niche where ambient and post-rock blur together, but Eyes Like Pools parts ways from worriedaboutsatan by swapping out electronic beats for Green’s achingly lovely violin melodies. While the more ambient side of Marta Mist’s current vision is appropriately warm and immersive, those pieces tend to be quite brief and the more substantial string-driven pieces are the true heart of the album (and it is a fiery heart indeed).

This is my first exposure to this UK-based collective centered around Gavin Miller (worriedaboutsatan) and Sophie Green (formerly of Her Name is Calla), but they have been fitfully releasing albums for more than a decade now. Their last major release, Scavengers, was back in 2016 on Time-Released Sound, so Eyes Like Pools both ends a lengthy hiatus and marks the collective’s first appearance on Athens’ sound in silence label. Much like Miller’s worriedaboutsatan project, this latest statement from Marta Mist occupies a vaguely cinematic stylistic niche where ambient and post-rock blur together, but Eyes Like Pools parts ways from worriedaboutsatan by swapping out electronic beats for Green’s achingly lovely violin melodies. While the more ambient side of Marta Mist’s current vision is appropriately warm and immersive, those pieces tend to be quite brief and the more substantial string-driven pieces are the true heart of the album (and it is a fiery heart indeed).

The album opens with a pleasant yet deceptive intro of gently rolling piano arpeggios before unveiling the first of its three major highlights: the 14-minute “Alway On.” The piece begins modestly enough with some lovely violin drones, but tendrils of melody soon start to appear and a low industrial hum gradually blossoms into a slow-moving chord progression driven by deep, warm bass tones. There are admittedly a couple of moments where it starts to err a bit too far towards soft-focus prettiness for my taste, but Green’s sliding, smearing, and occasionally snarling violin carves through the bliss haze enough to keep me transfixed regardless. More importantly, “Always On” delighted me with a very cool and unexpected ending in which echoey guitar chords slowly emerge from the ambient haze like a vengeful rockabilly ghost.

The following “Lie on Your Side” is yet another gem, as a simple call-and-response violin melody gradually swells into a complexly layered tour de force of churning drones, looping strings, buzzing bass wreckage, and howling intensity in just six minutes. I especially love how the sensuous string drones at the heart of the piece seem to expand and intensify until the surrounding structure starts to burn up. I am also quite fond of the dream-like, stuttering loop bliss of “I've Drawn you a Map,” but it sadly does not stick around very long. Fortunately, “We Have Business to Attend to” ends the album with one final epic that stretches and strains towards transcendence (or at valiantly strains towards being an appropriate soundtrack for The Rapture). In any case, “We Have Business..” is an absolutely gorgeous piece, as mournful strings ascend heavenward from an intensifying roar of choral loops, distortion, and lingering smears of decay. Notably, Miller and Green also pull one last unexpected and emphatic ending out of their hat, as the final minute sounds like a wall of amps bursting into flames as the explosive finale to a disconcertingly feral space rock gig.

This album properly blindsided me, as Green and Miller brought an intensity and inventiveness to these pieces that I definitely did not anticipate at all. If there are any other ambient collectives out there who are planning to end a long hiatus, this is the template for doing it right (and doing it memorably): no one needs another album of pretty synth drones, but everyone needs a good distortion-gnawed howl of catharsis or ecstatic release.

Read More

- Duncan Edwards

- Albums and Singles

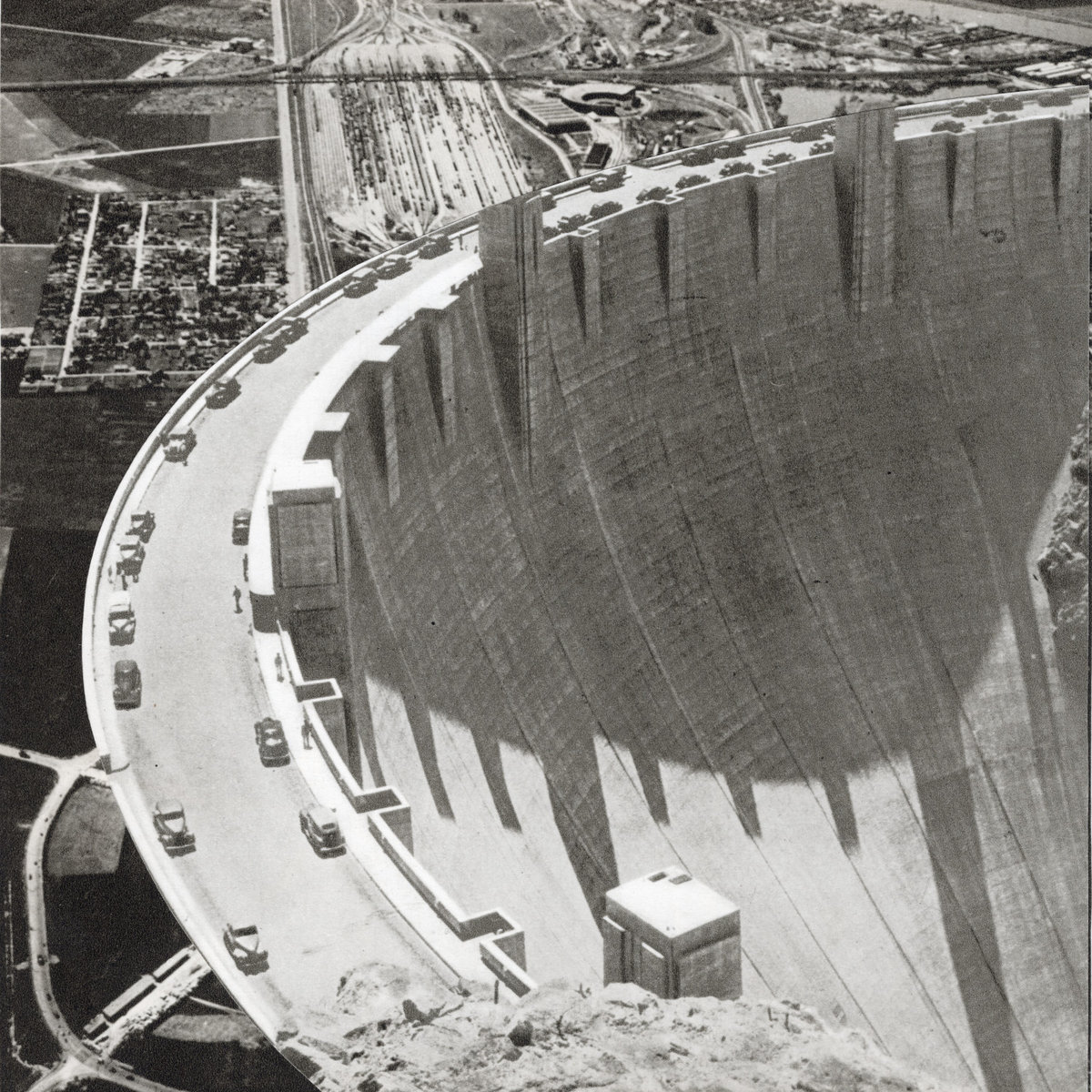

William Basinski recorded this music during his time living in San Francisco, when he presumably visited Clocktower Beach. Considering that Basinski once created On Time Out Of Time—music in tribute to quantum entanglement and the theories of Einstein and Rosen, and Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky, using source recordings of the 1.3 billion year old sounds of two distant massive black holes—undoubtedly the subject matter of The Clocktower at the Beach is one of his more straightforward creations. Fair enough, it is one of his earliest drone pieces, yet his methodology is as intriguing as anything he's done, and (most important of all) the music is a memorable journey into the sadness of things. Back to "mono no aware," then.

William Basinski recorded this music during his time living in San Francisco, when he presumably visited Clocktower Beach. Considering that Basinski once created On Time Out Of Time—music in tribute to quantum entanglement and the theories of Einstein and Rosen, and Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky, using source recordings of the 1.3 billion year old sounds of two distant massive black holes—undoubtedly the subject matter of The Clocktower at the Beach is one of his more straightforward creations. Fair enough, it is one of his earliest drone pieces, yet his methodology is as intriguing as anything he's done, and (most important of all) the music is a memorable journey into the sadness of things. Back to "mono no aware," then.

About that methodology: it seems that Basinski recorded the night shift at a sausage factory on a battery operated portable cassette player, then made this music from that source material chiefly using a Norelco Continental four speed reel to reel tape recorder. Looping and speed tampering is all very well on paper, but thankfully Basinski's ear is such that there is not the slightest trace of anything horrible, gimmicky, nonsensical, or even dull. Broken 1950s televisions, scavenged from the streets by James Elaine, were also used, I'm unsure exactly how but presumably as another sound source.

As with any good drone, or extended ambient work, there comes a point or points where I must have stopped actively listening, because later I realize "oh that's still going on." The music can also suddenly become absolutely riveting. At least that's the kind of journey I go on. It's a bit like Lord Buckley's "Subconscious Mind" track, wherein he describes driving along in a car when suddenly a girl pops into his head who occupies his thinking to the extent that he zones out before being shocked to discover he's driven the last five miles with his mind elsewhere. Not that we've ever done that, eh? Perish the thought!

Keep in mind that I couldn't construct a coherent theory as to how and why a cheese sandwich exists, yet I feel confidently able to state that, as with much of Basinski's work, there is a sense on this album that the music compresses centuries into a few moments while simultaneously expanding those moments into a piece essentially without beginning or end; suggesting everything, explaining nothing. The album title suggests time stopped, time passing, the ebb and flow of tides, a snapshot of a place, a personal memory. The music evokes grief, decay, sadness, and an intersection of dreams and wishes. The cover art is an excellent match, too, and no wonder. Offshore 2 (2022) a piece composed of acrylic and metallic paint, graphite, razor cuts on board by James Elaine in the style of Paul Klee.

Basinski's career, well it's impossible to discuss without mentioning his landmark release The Disintegration Loops. I have only heard that all the way through once; arguably the only way to approach such a monument. Loops is the perfect example of unintended consequences arising from technology and a composer being open and able to recognize when the universe is bringing something into being without specific intent from the artist. He has recently taken a splendid tangent with the wildly different Sparkle Division, his project with Preston Wendell. Their first release disguised Basinski's presence almost entirely; but several tracks, such as "No Exit" and "Oh No You Did Not!" do seem almost to fall to pieces as they glide along and fade away, as if departing for a separate recording titled Jazz from the Entropy Lounge which exists only in another multiverse. The Clocktower at the Beach is just as enjoyable. Close in texture to the early feedback work of Eliane Radigue, it could definitely work as a soundtrack; perhaps if someone decides to make a movie of Steve Erickson's books, such as Tours of The Black Clock, Rubicon Beach, or Days Between Stations. This is a fascinating and engrossing glimpse into Basinksi's creativity. Now I want him to release a recording commemorating Denton Square.

Read More

- Anthony D'Amico

- Albums and Singles

This is apparently the twelfth solo album from Berlin-based double bassist Mike Majknowski, but—far more significantly—it is also the follow up to 2021's killer Four Pieces and is very much in the same vein. That vein lies somewhere between loscil-style dubwise soundscapes and the austere sophistication of classic Tortoise or early Oren Ambarchi, which is certainly a fine place to set up shop, but that is merely the backdrop for some truly fascinating forays into sustained, simmering tension and exquisitely slow-burning heaviness. Unsurprisingly, I am like a moth to a flame when it comes to longform smoldering minimalism and I can think of few artists who can match Majknowski's execution, as he consistently weaves magic from little more than a few moving parts and a healthy appreciation for coiled, seething intensity.

This is apparently the twelfth solo album from Berlin-based double bassist Mike Majknowski, but—far more significantly—it is also the follow up to 2021's killer Four Pieces and is very much in the same vein. That vein lies somewhere between loscil-style dubwise soundscapes and the austere sophistication of classic Tortoise or early Oren Ambarchi, which is certainly a fine place to set up shop, but that is merely the backdrop for some truly fascinating forays into sustained, simmering tension and exquisitely slow-burning heaviness. Unsurprisingly, I am like a moth to a flame when it comes to longform smoldering minimalism and I can think of few artists who can match Majknowski's execution, as he consistently weaves magic from little more than a few moving parts and a healthy appreciation for coiled, seething intensity.

The album consists of two side-long pieces ("Spiral" and "Later") that feel like divergent variations on a similar theme. "Spiral" opens with little more than a simple bass pattern, the pulse of a lonely high hat, and semi-rhythmic washes of bleary feedback or ravaged synth. There is also something resembling a minor key vibraphone melody languorously weaving through the mix, but it feels more like impressionistic coloring rather than a focal point. Gradually, a pulsing synth motif fades in that feels out-of-sync with the rest of the rhythm, giving the piece an organically shapeshifting feel that propels it into increasingly frayed and subtly unpredictable terrain: reliable rhythms start to falter, textures become more distorted, and the relationship between the various parts is increasingly in flux. It calls to mind a spider patiently spinning an incredibly intricate web while also resembling a state of suspended animation that is increasingly gnawed by an unsettling outside darkness.

While mostly built from similar materials, "Later" takes a very different path than its predecessor, opening with an industrial "locked groove" rhythm that is coupled with an insistently looping bass pulse. Gradually, however, additional notes creep into the bass pattern to transform the rhythm into something a bit more fluid, though the mechanized foundation boldly reasserts later in the piece. If "Later" was only an experiment in subtly shifting industrial rhythms, it would still be an impressive and absorbing piece, but a sickly swooping sound joins the churning and hiss-ravaged factory floor rhythm in the final minutes to elevate the piece into something more intense and haunting. Aside from the warmth of the bass line, it almost feels like a "lost classic" industrial tape from the '80s, except that tape murk has been replaced by crystalline clarity and precision-engineered dynamics. That clarity suits Majknowski's tightly choreographed artistry beautifully, as he expertly wields space to create a vacuum in which every subtle change or manipulation is felt deeply enough to transform and shape the whole. While I admittedly have a strong predisposition towards any virtuosic instrumentalist who spends a lifetime mastering their instrument so thoroughly that they eventually come out the other side to make hyper-minimalist music (like the two- or three-note bass lines on this album, for example), Coast feels like an objectively brilliant album to me (or at least an absolute master class in the manipulation of dynamics and tension).

Read More