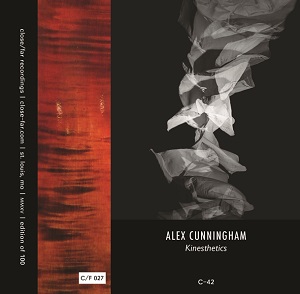

Alex Cunningham, "Kinesthetics"

It wasn’t an accident of the imagination that inspired Pieter Bruegel the Elder to portray undead soldiers playing musical instruments in his Triumph of Death. Long before various religious sects decided that dance was an expression of unchecked desires, and therefore a temptation to be avoided, philosophers like Plato and Aristotle had connected music to moral incontinence. For Aristotle, the aulos, a double reed flute, was especially problematic because it prevented the player from speaking and because it drove men to irrational behavior. Bruegel, perhaps less concerned with prodigality than with mockery, chose a hurdy-gurdy, a violin, and drums for his skeleton warriors, but in the bottom-right corner of Triumph painted two oblivious nobles busy with a lute, neither panicking nor struggling against their fate. Their heads might as well be buried in the sand, their asses branded with the word "coward." Equally well known is Italian violinist and composer Niccolò Paganini who, because of his talents, his appearance or maybe out of jealousy, was rumored to have made a deal with Satan, securing him a legend and at least one painfully bad dramatic biography directed by Bernard Rose. That gets us back to the modern association of the violin with the devil, and to Alex Cunningham’s Kinesthetics, his debut solo violin album on the Close/Far label.

It wasn’t an accident of the imagination that inspired Pieter Bruegel the Elder to portray undead soldiers playing musical instruments in his Triumph of Death. Long before various religious sects decided that dance was an expression of unchecked desires, and therefore a temptation to be avoided, philosophers like Plato and Aristotle had connected music to moral incontinence. For Aristotle, the aulos, a double reed flute, was especially problematic because it prevented the player from speaking and because it drove men to irrational behavior. Bruegel, perhaps less concerned with prodigality than with mockery, chose a hurdy-gurdy, a violin, and drums for his skeleton warriors, but in the bottom-right corner of Triumph painted two oblivious nobles busy with a lute, neither panicking nor struggling against their fate. Their heads might as well be buried in the sand, their asses branded with the word "coward." Equally well known is Italian violinist and composer Niccolò Paganini who, because of his talents, his appearance or maybe out of jealousy, was rumored to have made a deal with Satan, securing him a legend and at least one painfully bad dramatic biography directed by Bernard Rose. That gets us back to the modern association of the violin with the devil, and to Alex Cunningham’s Kinesthetics, his debut solo violin album on the Close/Far label.

In his music, the St. Louis-based Cunningham makes no mention of the Great Adversary or any other power of darkness, but the name he chose for his debut gets right to the relationship between violin and movement, and more specifically to the sense of muscular effort and strength felt within the human body. Cunningham’s technique is, in one sense, muscular. He cuts and grinds at his instrument and digs into its strings, cutting off pitch and wrenching noise from them instead. As a result, the constant back-and-forth of the bow, the way it rocks and darts over the instrument, comes to the fore, until it is more the subject of the music than the melodies or even the instrument itself. On a song like "Drop Leaf," movement becomes a microscopic event, something that depends on tiny movements and minuscule physical properties, enough so that the violin is almost completely disguised. On "The Cage Knocked the Cloth Over" it breaks down even further, into waves of color and dispersing vapors.

Alex has a lighter touch too and finds space for more lyrical expressions in the same song, for small interludes that sound, for lack of a better term, classically executed. "Kinesthetics No. 2" and "Ida" both also contain similar passages, as do nearly all the other songs to varying degrees. Though improvised, Kinesthetics is clearly the product of someone who has been trained to play the instrument. Watching video of him on his website, it’s easy to see that Cunningham can work the fingerboard with precision, and his command of dynamics, including some wrist-breaking transitions from light and sonorous to blurred and taut, is on constant display.

The way he cobbles his performances together, from both traditional and extended techniques, is reminiscent of his collage work as a visual artist, which is formally meticulous and materially playful. That is another kind of movement Cunningham captures, between two spheres of musical expression. In the one, his playing might have once been called devilish, and certainly energetic, prone less to reason and more to feeling. In the other, he’s an improviser testing where and how different approaches fit, and whether they can stay within the same orbit for long. With Kinesthetics he posits one solution, which is to smear the two together until they cease to be at odds.

samples: