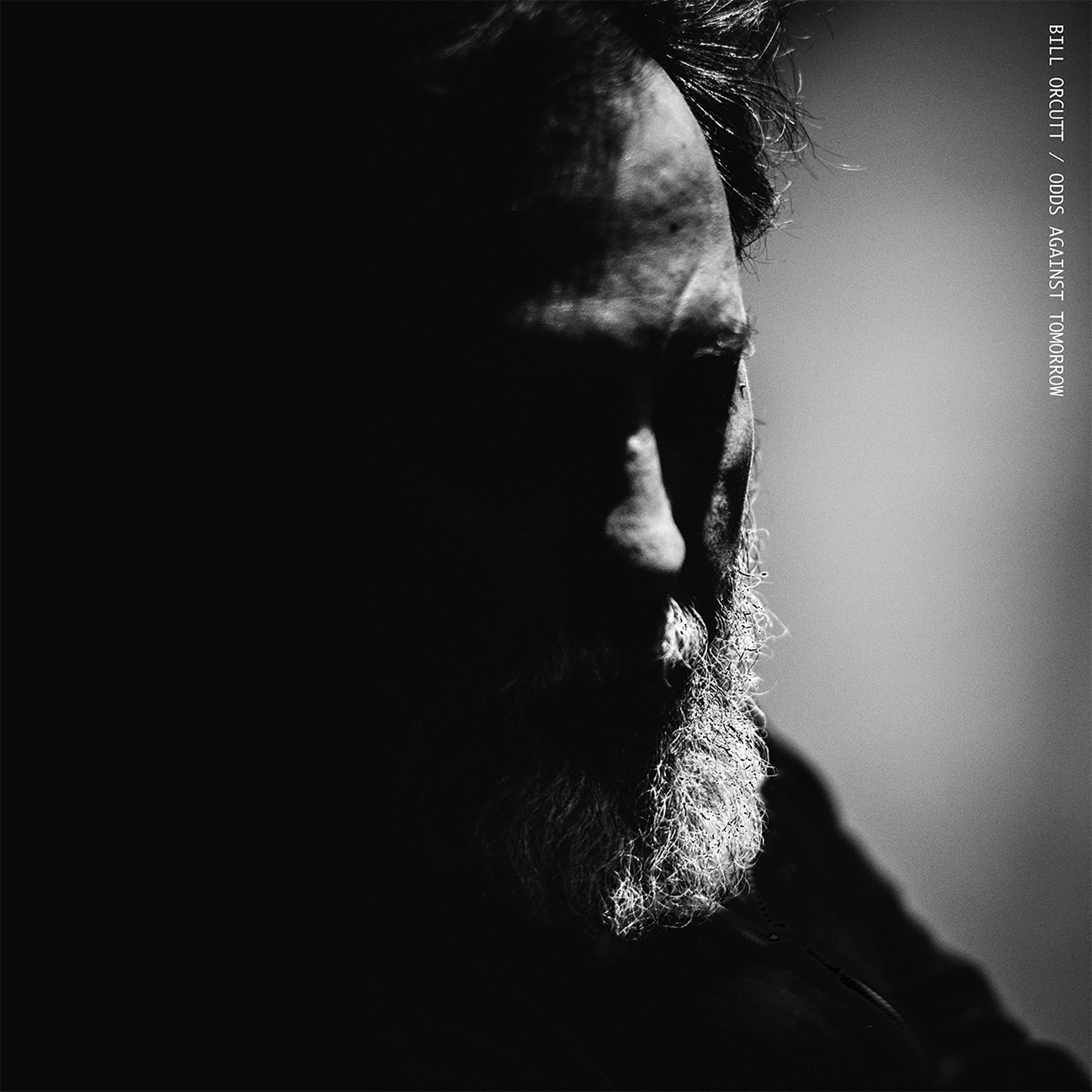

Bill Orcutt, "Odds Against Tomorrow"

Bill Orcutt's career admittedly had quite an abrasive and chaotic start with Harry Pussy, but it has always been abundantly clear that he is one of the more idiosyncratic and explosive guitar stylists on the planet. It was not until he started releasing solo albums, however, that I began to feel like he was some kind of outsider genius rather than a room-clearing noise maniac (though I imagine it was impossible to convey any emotion more subtle than "baseball bat to the face" with a human volcano like Adris Hoyos behind the drum kit). In any case, Orcutt's late-career shift to more intimate, melodic material has been nothing short of a revelation and 2017's self-titled studio album was the brilliant culmination of that evolution. With this follow-up, Orcutt occasionally hits some similar highs, but Odds Against Tomorrow is more of an intriguing transitional album or lateral move than another instant classic, as he mostly dispenses with playing standards to focus on his own compositions and some very promising experiments with multi-tracking.

Bill Orcutt's career admittedly had quite an abrasive and chaotic start with Harry Pussy, but it has always been abundantly clear that he is one of the more idiosyncratic and explosive guitar stylists on the planet. It was not until he started releasing solo albums, however, that I began to feel like he was some kind of outsider genius rather than a room-clearing noise maniac (though I imagine it was impossible to convey any emotion more subtle than "baseball bat to the face" with a human volcano like Adris Hoyos behind the drum kit). In any case, Orcutt's late-career shift to more intimate, melodic material has been nothing short of a revelation and 2017's self-titled studio album was the brilliant culmination of that evolution. With this follow-up, Orcutt occasionally hits some similar highs, but Odds Against Tomorrow is more of an intriguing transitional album or lateral move than another instant classic, as he mostly dispenses with playing standards to focus on his own compositions and some very promising experiments with multi-tracking.

It is both remarkable and amusing that the most radical change to Orcutt's aesthetic on Odds Against Tomorrow is that he allowed himself the luxury of multi-track recording on three songs (he is closing in on three decades of recording at this point).In a sense, that decision marks the end of an era, as one of Orcutt's more appealing traits has always been his no-frills spontaneity and devotion to raw, undiluted expression.He might be a solo guitarist with a fondness for The Great American Songbook, but a strong case could be made that he is also the last No Wave artist standing, as he remained devoted to visceral, unpolished passion long after everyone else had moved on.While certainly admirable, such an approach admittedly has extreme limitations, as a dazzling technical performance does not always translate into a great album: the world is littered with disappointing records that proudly proclaim that they were performed live with no overdubs or studio enhancements.Conversely, there are even more albums where artists suck the life out of their work through misguided perfectionism.The trick, of course, is to find a balance between those opposing impulses that best suits the material. I do not think Orcutt is in any danger of becoming hopelessly enthralled by the limitless possibilities of modern recording techniques anytime soon (he recorded this album in his living room rather than returning to a studio), but he definitely shows a strong intuition for making the most out of overdubbing.In fact, my favorite two pieces on the album are ones in which Orcutt accompanies himself.

The first highlight is the opening title piece, which has a lazily lyrical melody that harkens back to the standards cannibalized on Bill Orcutt.It is an elegantly simple piece with an appealingly casual feel, as the second guitar provides a languorously unfolding backdrop of chiming chords and arpeggios for Orcutt to solo over.The solo itself is similarly unhurried, spacious, and quietly lovely, but there are occasional eruptions of violence where the melody is fleeting transformed into strangled, scrabbling snarls of notes.It is a perfect illustration of what makes Orcutt's recent work so striking and uniquely beautiful, as he has found a way to sound both sublimely poetic and unpredictably prone to flashes of slashing violence.Consequently, he manages to avoid ever lapsing into mere prettiness, as there is always a fiery and primal soulfulness ready to tear viscerally through even the gentlest melody.Moreover, such eruptions always feel appropriate and fully earned when they happen.For the most part, the difference between a great Bill Orcutt song and a decent Bill Orcutt song lies solely in the melodic strength of the piece that is being deconstructed and ripped open, which is why exploring timeless, familiar melodies has served him so well in the past.The only real nod to such evergreen standards this time around, however, is a brief, tender, and quaveringly chorus-heavy rendering of "Moon River."It is a strong piece, but it is an anomaly.In fact, just about all of the best pieces on Odds Against Tomorrow are anomalies, as the album description notes that it is "a rock record — almost."I would describe it more as "a blues record — almost" myself, as pieces like the slow-burning "Already Old" and the Elmore James-inspired "Stray Dog" are explicitly blues-based.Such pieces are the core of the album, but they are quite a far cry from Tomorrow's second highlight, the pulsing Glenn Branca-esque minimalism of "A Writhing Jar."

On balance, there are more inspired pieces than lulls or misfires on Odds Against Tomorrow, but the inclusion of "Stray Dog" illustrates the sometimes uneven and perplexing nature of the album: it is essentially just a standard blues vamp with standard blues scale soloing (albeit played on a four-string guitar).It reminds me of a critique I once read which stated that a band was great before they had completely figured out what they were doing, but disappointing once they actually became competent enough to successfully imitate their influences (which is what they were subconsciously trying to do all along).A straight homage to classic blues is not particularly interesting and can be readily found in small-town biker bars all over the US.Hearing classic blues pass through the filter of Bill Orcutt's vision to emerge in razor sharp and unrecognizable form, on the other hand, is wonderful.After hearing the latter, it is very hard to embrace the former.On a related note, I find Orcutt to be quite a fascinating enigma, as he seems perversely and almost exclusively fixated on cultural phenomena that occurred before he was born: this album borrows its name from a 1959 film noir, Elmore James died in 1963, and the double-tracking was purportedly inspired by a 1952 John Lee Hooker single.And, of course, the golden age of The Great American songbook was already waning in the '50s (though "Moon River" managed to belatedly sneak in in 1961).How Orcutt manages to translate a nostalgia for both the dark side and the cheery illusion of the 1950s' American Dream into something so vital and bracingly contemporary is beyond me, but I am damn glad he figured out a way to do it (either consciously or otherwise).While Odds Against Tomorrow is an imperfect album, it is an imperfect album by a legitimate iconoclast who remains one of the most compelling guitarists around.

Samples can be found here.