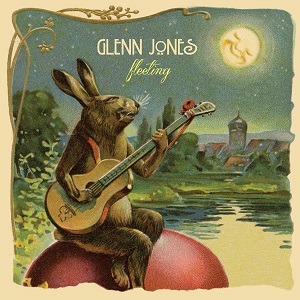

Glenn Jones, "Fleeting"

On his last couple of albums, Glenn Jones has let the world into his music. Back in 2011, the rattle of Commonwealth Avenue’s B-line train snuck into The Wanting. More or less an invisible addition, it was the consequence of recording in an apartment that sits on one of Boston’s busier thoroughfares. My Garden State opened the doors and windows and walked out into the New Jersey neighborhood of Glenn’s youth. It has a thunderstorm and chimes and an annotation about frogs, and they are more than just filigree on the proverbial fretboard. "Alcouer Gardens" would be a different song without the rain and thunder, and the non-stringed sounds add details to the loose narrative announced in the titles. Now comes Fleeting, Jones’s sixth solo album, recorded in Mount Holly, New Jersey with Laura Baird. The studio windows are open again and there are birds in the trees, but the emphasis placed on the influence of people and places cuts at the idea that there is an inside and an outside to begin with. It argues that music, often tucked away inside headphones or living rooms or performance spaces, is more than a confined curiosity of the wider human world.

On his last couple of albums, Glenn Jones has let the world into his music. Back in 2011, the rattle of Commonwealth Avenue’s B-line train snuck into The Wanting. More or less an invisible addition, it was the consequence of recording in an apartment that sits on one of Boston’s busier thoroughfares. My Garden State opened the doors and windows and walked out into the New Jersey neighborhood of Glenn’s youth. It has a thunderstorm and chimes and an annotation about frogs, and they are more than just filigree on the proverbial fretboard. "Alcouer Gardens" would be a different song without the rain and thunder, and the non-stringed sounds add details to the loose narrative announced in the titles. Now comes Fleeting, Jones’s sixth solo album, recorded in Mount Holly, New Jersey with Laura Baird. The studio windows are open again and there are birds in the trees, but the emphasis placed on the influence of people and places cuts at the idea that there is an inside and an outside to begin with. It argues that music, often tucked away inside headphones or living rooms or performance spaces, is more than a confined curiosity of the wider human world.

Fleeting begins with the sprightly see-saw rhythm of "Flower Turned Inside-Out." It’s a cheerful song that contrasts the up-and-down pulse of alternating strings with Glenn’s dexterous left hand, which snaps, rolls, and darts across the fretboard in a kind of dance. The melodies and harmonies are bright and inventive, sounding both controlled and spontaneous, and the mood is playful—this is Glenn Jones in a familiar place letting his mind and instrument meld into a single intuitive apparatus.

Then the light goes out and the rhythm unwinds. Jones’s chords transform into floating clouds, as if he were playing them and then getting out from his chair and walking around them. Time slows down and space collapses to a free-moving point. The rest of the album is calmer. Not exactly darker, but aware of the shades of joy and sadness that come with remembering the past and seeing that it’s different from the future.

"In Durance Vile" is where the inside and outside have their first overt meeting. After a short run of angular and surprising melodies, Glenn lets out a broken chord and pauses for a moment to let it resonate in the room. At that exact moment a bird trills three or four times and pauses, like it’s waiting to see if Glenn will sing back. Everything about the song is gorgeous: its unmoored structure, which bends and stretches in all the right places, its tight melodies and unexpected developments, and Jones’s technique—the way he uses volume, tempo, and the sharpest of sharp dynamics, keen enough to cut the toughest ears in two. Together they give "In Durance Vile" the semblance of infinite variety, and yet when that bird lands in the silences between the notes, something extra pops. Call it synchronicity or coincidence, it puts Glenn in a space and time that is not the abstract space and time of a modern recording.

It’s the same space and time in which Glenn’s influences, not to mention his friends, have lived and died—Robbie Basho and Jack Rose, John Fahey and Jimi Hendrix. It’s the place where people celebrate their loved ones and remember them in all of their complexity, and with all the complexity that remembrance brings. Listen to the way Jones weaves happiness and longing together on "Mother’s Day." Listen to how he commands concrete images, moments of doubt, and uncertain feelings, pulling them all in a line when he wants with a big bluesy hook and an uncanny sense of timing. Notice how he invokes personal feelings with understated banjo lines on "Spokane River Falls," how he refuses to commit to sentimental nostalgia but simultaneously evokes familiarity and belonging. Pay close attention to the enormity in "Robbie Basho as a Young Dragon," which is curious and firm, both seeking and reaffirming, as is the way with good friends.

These connections are all sounds from the outside too, received from beyond and returned to it, with something new added. If that sounds magical or mystical it’s because Fleeting deals with magical and mystical materials. Glenn closes the album with "June Too Soon, October All Over," an extroverted panegyric to the joys of the northeast’s warmer months. It ends with the omnipresent chirping of crickets, a whole field of them trumpeting away as twilight fades to dusk. Time resumes its forward movement here, toward colder temperatures, darker beers, and shorter light, but the switch from atemporal introspection to the usual procession of events is fluid, suggesting we can move in and out of either mode at will—that, in fact, the two coexist, just like the inside world and the outside one, the soul and the universe. There’s a Wallace Stevens poem that begins, "The soul, he said, is composed / Of the external world." It ends claiming, "The dress of a woman of Lhassa, / In its place, / Is an invisible element of that place / Made visible." Glenn Jones might agree. At the very least, he knows what it means to make the invisible visible.

samples: