Greg Stuart & Ryoko Akama, "Kotoba Koukan"

Although she composes scores meant for others to perform, there are times when Ryoko Akama seems intent on preventing performances of her work. Like when she asks, on Kotoba Koukan’s "con.de.structuring," for two or more collaborators to play three "soundless" sounds at fixed intervals without the help of a clock or a stopwatch, or when she inserts an observation about silent letters into "e.a.c.d." that suggests silence will be as essential to its realization as positive sound. Even with a talented interpreter like Greg Stuart around to meet such challenges, questions are bound to arise in the audience, who might wonder how a sound could ever be soundless or how a piece of music apparently devoted to silence could end up being so concrete and loud. Attentive listening may resolve some of these quandaries, but is as likely to generate new ones. Ambiguity and irresolution appear to be at the heart of the matter, at least in part, and besides, focusing on the conundrums in Akama’s work overlooks its power and impact. Ryoko and Greg’s music works on the body and mind in equal proportion, tempting interpretations and provoking reactions with confrontational sounds and understated twists.

Although she composes scores meant for others to perform, there are times when Ryoko Akama seems intent on preventing performances of her work. Like when she asks, on Kotoba Koukan’s "con.de.structuring," for two or more collaborators to play three "soundless" sounds at fixed intervals without the help of a clock or a stopwatch, or when she inserts an observation about silent letters into "e.a.c.d." that suggests silence will be as essential to its realization as positive sound. Even with a talented interpreter like Greg Stuart around to meet such challenges, questions are bound to arise in the audience, who might wonder how a sound could ever be soundless or how a piece of music apparently devoted to silence could end up being so concrete and loud. Attentive listening may resolve some of these quandaries, but is as likely to generate new ones. Ambiguity and irresolution appear to be at the heart of the matter, at least in part, and besides, focusing on the conundrums in Akama’s work overlooks its power and impact. Ryoko and Greg’s music works on the body and mind in equal proportion, tempting interpretations and provoking reactions with confrontational sounds and understated twists.

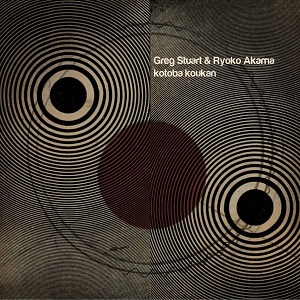

Matthew Revert’s artwork for Kotoba Koukan conveys almost perfectly the quality of the music inside. The simplicity of the design, the complexity of the patterns created by the concentric circles, and the evocation of sound’s physical properties all point to the album’s most potent and immediate attributes. Before the compositional strangeness of "e.a.c.d." can even be guessed, the hefty crunch of its textured electronics and cavernous tones is felt, which together produce the strong impression that Greg and Ryoko have captured the activities of physical objects operating independently in the world. The sound of the piano, the call of birds, and the persistent and rough friction of various surface noises all spotlight the material conditions necessary for that song’s existence, and so emphasize the presence of things, not just their reproduction.

The catch is that the score, which is not included in the liner notes, deals with far less defined entities. It contains such ambiguities as "long" and "like that" and "like a chimney," all arranged along a line that begins at a point marked 0’00" and that ends at 20’00". Situated in an area roughly halfway across that line is the phrase "silent letter is a letter that is not pronounced, yet without it the word makes no sense," with each instance of the titular letters emphasized, suggesting that there is an analogous entity at work in the music, present but silent or otherwise camouflaged.

Repeat listens present multiple candidates: a continuous fundamental tone that may or may not rise as the piece proceeds, the constant hum of electronic instruments, or maybe the various found sounds scattered throughout the piece, like little reminders of the objects behind the noises. The score itself could also be the music's silent ingredient, there but invisible behind Akama and Stuart’s performance choices. Whatever the answer might be in this particular interpretation, it could be different in a hundred others. The idea is not to crack the performance’s code, but to recognize how all the different parts relate, and perhaps to see or feel each sound as one element in a more complex and ultimately indefinable system.

With "con.de.structuring," Ryoko and Greg play with the enigmatic flow of time and call into question its atomistic measurement. The score quotes English writer, painter, and poet John Berger on the subject of visual art and time, and asks for all involved performers to select three "soundless" sounds to be played at precise intervals without the assistance of a timepiece. Invisible or immeasurable elements once again determine some aspect of the music’s performance, and again the musicians focus on sounds that outline spaces or suggest the presence of objects: radio fuzz, sonar pings, geological drones. It is as if, in the absence of ordinary time, Akama and Stuart intuitively sought out other means of measuring the extent of their environment. Instead of the usual relationship, sound becomes the standard for evaluating space and time.

Kotoba Koukan concludes with "border ballad" and "fade in and out procedure." The former sounds like an improvisation on the phenomena of friction and erosion utilizing wood, tape, glass beads, racquetballs, compressed air, sand, and slate. The latter is a matchlock explosion of colors and patterns achieved by the slow introduction and removal of five (presumably) electronic sounds chosen by Greg Stuart, for whom the piece was written. The simple mechanics of addition and subtraction are all he requires to cultivate the album’s most resounding, spacious, and finessed piece. The twittering of different high end signals, the pulse of the song’s throbbing low-end, and the ebb and flow of both form an impressive wall of sound capable of rattling the windows and shaking the floor. Buried beneath that impressive wave of turbulence are small artifacts that imply a physical process is working behind the scenes, like the bowing of a drum head or the vibration of a piece of metal. Whether their origins can be accurately deduced, and whether the meaning behind Akama’s instructions can be accurately interpreted, is ultimately unimportant. Alien or familiar, rational or ineffable, the sounds connect and leave an impression on environment and audience alike.

samples: