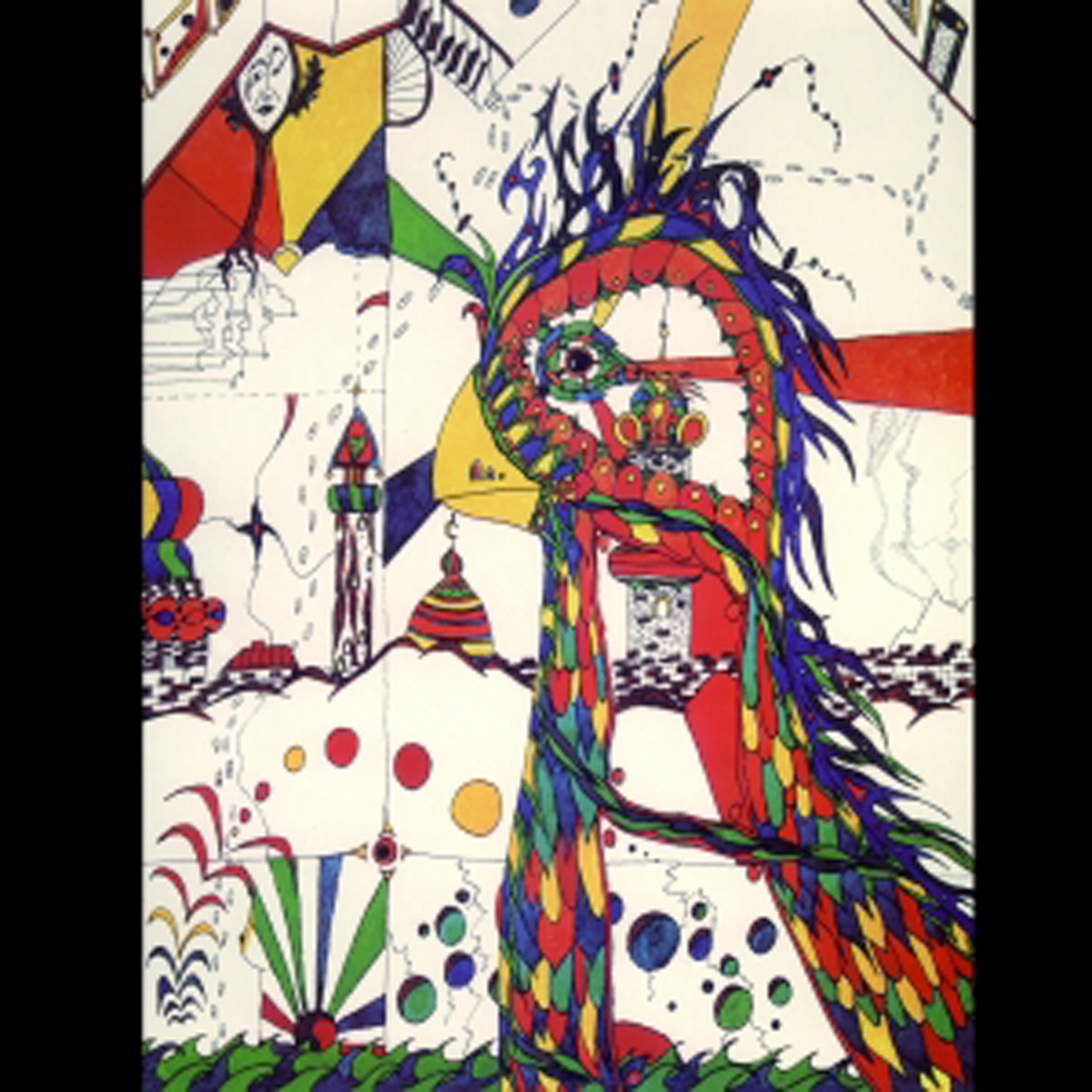

Günter Schickert, "Samtvogel"

Important Records has issued many great albums over the years, but it just occurred to me today that they have quietly become one of the best-curated reissue labels around.  Case in point: this visionary 1974 suite of hermetic, hallucinatory solo guitar compositions.  Originally self-released, Samtvogel was later reissued twice by the legendary Krautrock label Brain, which is something of a deceptive pairing. Although he worked as Klaus Schulze's roadie and assistant and had an active presence in Germany's free-jazz and space music scenes in his own right, this surprisingly dark and obsessive early effort bears little resemblance to anything else in the Krautrock canon, aside from perhaps Manuel Göttsching's landmark Inventions for Electric Guitar (which was not released until the following year).

Important Records has issued many great albums over the years, but it just occurred to me today that they have quietly become one of the best-curated reissue labels around.  Case in point: this visionary 1974 suite of hermetic, hallucinatory solo guitar compositions.  Originally self-released, Samtvogel was later reissued twice by the legendary Krautrock label Brain, which is something of a deceptive pairing. Although he worked as Klaus Schulze's roadie and assistant and had an active presence in Germany's free-jazz and space music scenes in his own right, this surprisingly dark and obsessive early effort bears little resemblance to anything else in the Krautrock canon, aside from perhaps Manuel Göttsching's landmark Inventions for Electric Guitar (which was not released until the following year).

Notably, Samtvogel ("silk bird") was Schickert's first album, which is both remarkable and weirdly appropriate.  The "appropriate" bit stems from the fact that it is clearly the work of someone who just discovered how cool echo sounds on a guitar and set about abstractly experimenting with it with no real aspirations for anything more.  The "remarkable" aspectq, however, lies in both the single-mindedness with which Schickert pursued his experiments and the self-assuredness of his bold divergence from the exciting, fertile scene around him.  Günter clearly had a unique, fully formed vision from the very beginning and set about realizing it by whatever means were at his disposal, which were quite modest.

Due to the limited, primitive equipment Schickert had on-hand, the recording of these three pieces actually took three months, as all of the heavy lifting was accomplished with just a guitar, an amp, his voice, and two tape recorders.  Given the density and complexity of some passages, that is difficult to imagine, but that is precisely why the recording took so long: Günter had to painstakingly assemble the various layers by recording himself playing along each previous tape, starting over again from scratch every time he made a mistake.  As frustrating as that process must have been, the naked, lo-fi quality of these recordings actually works in Samtvogel's favor, as Schickert's brand of psychedelia feels genuinely, uncomfortably warped rather than like anything resembling mere studio artifice.

Despite that limited palette, each of Samtvogel's three pieces is quite distinctive.  The shortest, "Apricot," opens the album on a fragile, woozy, languorous and uncharacteristically song-like note.  The piece is also quite a cryptic one, as the few words that I am able to make out seem to be about apricot brandy, a topic which sits uncomfortably with the lonely, echo-heavy nightmare the piece gradually becomes.  After that, Günter is very much done with attempting anything that resembles a song in the conventional sense, but he is more than happy to continue being disturbing and nightmarish.  As a result, the following two pieces are much longer and more abstract.  However, while they share a lot of similarities with one another in structure and trajectory, they ultimately wind up in very different places mood-wise.

"Kriegmaschinen, Fahrt Zur Hölle" (or "War Machines, Go to Hell") is the album's darkest, most unhinged piece and consequently its artistic zenith, as Schickert unleashes nearly 20 minutes of dense, dissonantly churningReich-esque minimalist patterns and panning vocal chants buffeted by queasily out-of-tune-sounding jangling.  After the appropriately explosive crescendo subsides, Günter launches into the closing "Walde" ("Forest") with a similarly roiling, massive assault of repeating patterns before unexpectedly giving way to a passage of swooning, melancholy beauty.  For better or worse, that oasis is an ephemeral one, as Schickert keeps a simmering tension rumbling in the background at all times.  Part of me wishes that Günter had allowed his more  warm and dreamlike passages to unfold in a less precarious, threatened manner, but I cannot deny that the piece's unstable and unpredictable nature makes for much better and more striking art than the more conventional piece my battered ears were hoping for.

While Samtvogel is undeniably a very unique, challenging, and forward-thinking recording from start to finish, its single most remarkable characteristic might be that it was not simultaneously Schickert's first and last album.  The mood of these pieces is so claustrophobic and paranoid that it is difficult to believe this was not an aural suicide note, evidence of terminal drug psychosis, or the last communique before Günter completely lost his mind.  Instead, Schickert somehow went on to record a similarly wonderful (if a bit more conventional) follow-up five years later in Überfällig, then later formed the revered (yet obscure) trio GAM.

As much as I loathe the woefully over-used term "lost classic," that is exactly what this album is, as it certainly meets my most exacting criteria: it sounded singularly challenging, audacious, and against-the-tide in 1974 and it basically still sounds completely unique.  Schickert wisely avoided any of the trends or clichés of the day (aside from hating war machines, obviously), so there is virtually nothing on Samtvogel that sounds particularly dated, ill-advised, or derivative.  Granted, there has been no shortage at all of echo-heavy psychedelic guitar voyages in Samtvogel's wake, but I suspect none of them have ever been quite as disconcertingly intimate and haunted-sounding as this one.