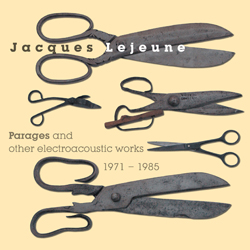

Jacques Lejeune, "Parages and Other Electroacoustic Works 1971-1985"

Robot Records’ three-CD retrospective of Jacques Lejeune’s music from the early 1970s and 1980s contains over three hours of heady electronic noise, surreal acoustic transformations, deconstructed field recordings, and disorienting aural splutter. It is a collection that spans 14 years and six electroacoustic compositions: one composed for ballet and inspired by Snow White, another inspired by the myth of Icarus, and others by landscapes, symphonic form, and cyclical movement, among other things. They flash with theatrical flair, jump unpredictably through minute variations, and churn chaotically, tossing fabricated scree and instrumental slag into the air. A 28 page bilingual booklet filled with photographs, drawings, and program notes accompanies the set, along with a 32 page booklet of interpretive poetry. In them, Lejeune, Alain Morin, and Yak Rivais offer up remarkably precise interpretations for each of the pieces, but the writing works much better as a rough guide to the visually evocative clamor of Lejeune’s electric transmissions.

Robot Records’ three-CD retrospective of Jacques Lejeune’s music from the early 1970s and 1980s contains over three hours of heady electronic noise, surreal acoustic transformations, deconstructed field recordings, and disorienting aural splutter. It is a collection that spans 14 years and six electroacoustic compositions: one composed for ballet and inspired by Snow White, another inspired by the myth of Icarus, and others by landscapes, symphonic form, and cyclical movement, among other things. They flash with theatrical flair, jump unpredictably through minute variations, and churn chaotically, tossing fabricated scree and instrumental slag into the air. A 28 page bilingual booklet filled with photographs, drawings, and program notes accompanies the set, along with a 32 page booklet of interpretive poetry. In them, Lejeune, Alain Morin, and Yak Rivais offer up remarkably precise interpretations for each of the pieces, but the writing works much better as a rough guide to the visually evocative clamor of Lejeune’s electric transmissions.

Jacques Lejeune’s musical career began auspiciously, at the famous Schola Cantorum de Paris, a private music school in the city’s Latin Quarter whose alumni include Edgard Varèse and Erik Satie. From there, he moved to the Conservatoire National Supérieur, where Adolphe Sax had once taught and where Igor Wakhévitch would eventually study, and labored under the tutelage of Pierre Schaeffer. He finished his education with François Bayle at the Groupe de Recherches Musicales, then joined the GRM in 1968 and became director of the Cellue de la Musique pour L’Image, or The Department of Music for Images, responsible for the production of sound and music for both theater and television.

By 1971 he had finished his first major composition, Cri, which premiered at the Royan Festival in 1972. It was Lejuene’s introduction to France and the first indication that his stint in the Images Department at the GRM had been as formative as the rest of his education.

Early on, Cri delivers brief, sometimes confounding glimpses of particular places and circumstances. Those images are held in focus just long enough to be recognized and then swept away: a marching band stomps through a busy street in the first movement, then disappears into the sound of French horns warming up before a performance; frogs croak in concert with crickets as sheets of tape noise flutter by imitating the sound of water; people laugh and conversations crash against bursting radio signals and gusts of analog distortion. In the second movement entire sentences survive, accompanied by reverse audio and a small gaggle of test tones. Exclamations leap out of the commotion and a radio transmission about Pakistan and the United States floats smoothly by, like a small town seen from the window of a passing train.

Lejeune introduces the skull-pounding sounds of a construction site later in the piece, but not before dampening the mood with desperate cries, rushing sirens, and the sinister crack of jackboots on concrete. The final movement is similarly ominous, though not as visually striking. Synthetic tones and surface noises replace the recognizable audio of the previous movements, and these become louder and gain more and more momentum until, near the finale, they crescendo in one long animal-like groan. The final minutes are calmer and more reflective, like a single wide-angle shot of the entire composition. The camera holds its gaze as people walk obliviously through the frame, and then the shot fades to a quiet, contemplative black.

Pieces like Parages, finished two years later, and Symphonie au bord d’un paysage, completed in 1981, also contain familiar worldly fragments, but in both works Lejeune so thoroughly transfigures his sounds that the familiar in them disappears. The focus shifts from the presentation of images to their transformation. Seagulls mix with squawking machines and squeaky hinges during one small section of Parages, calling our attention to the quiet pleasure of household noises. Moments later a series of sine waves and a brief flute passage swallow an entire church organ whole. Symphonie moves through several such transformations too: turntables start and stop, loose floorboards bend and creak under the weight of someone’s shoes, and numerous electronic reverberations zip like lightning through the mix. A few such reverberations repeat themselves, but most erupt in seemingly improvised and unrepeatable fits. Parages is particularly varied, moving at such a pace and with such variation that getting lost among its many mutations is inevitable.

It is an impressive and dynamic piece, but Robot could have easily named the collection after 1975’s Blanche-Neige, Lejeune’s incredible production for Fantasmes, ou l’histoire de Blanche-Neige, a ballet adapted from the Grimm Brothers’ version of Snow White by Yves Boudier and Catherine Escarret. Instead of simply composing music for the ballet, Lejeune creates an entirely self-sufficient audio version of the fairytale, using vocal snippets, sounds effects, and collaged motifs to represent the characters, places, and actions in the story. We can hear birds crying in the forest and monsters walking secretly in the dark during "Solitude of Snow White in the Nocturnal Forest," and Snow White, made wholly present by the inclusion of just a few fragmented sounds, gasps through every four tense minutes of it, panicking in response to the insects and night creatures that crawl by. Lejeune plunges into Snow White’s head and makes the tightness in her chest palpable one small detail at a time.

"The Hunter’s Race Dragging Snow White," on the other hand, gallops along quickly, pitched forward by vocal samples clipped so short they read as street percussion. Pots and pans and buckets belch muted vowels and abbreviated exclamations to the tune of sine waves and low, agitated drones. It is a frightening sequence, effective because all of its elements—the horse, the hunter, the sudden movements, Snow White’s confusion, and the gnarled forest path—are all depicted with perfect clarity.

Lejeune’s touch is delicate enough to handle light, color, and humor too. He takes pianos, harps, random stringed instruments, and bells to the chopping block, and then turns them into wavy, dream-like apparitions. During Snow White’s funeral, he uses awkward, honking voices to represent the dwarfs’ lamentations, rather than the usual melancholic singing. In place of the expected solemn dirge we get a line of mechanical toys bleating a lost and tuneless song. It’s a small bit of comedic relief, but a welcome one. Later, as the evil queen approaches her death, Lejeune cuts triumphant drums against operatic vocals modified to portray screams. It’s the sound of the queen protesting on the way to her execution, histrionic and larger than life. That spectacle carries through to the conclusion, where echoes of the prince’s earlier scenes are married to sounds used during Snow White’s solo appearances. The ballet ends happily, with birds singing and the happy couple riding off into a wobbly, harp-filled sunset—it’s a perfect storybook ending to a piece of music that, more than anything else, behaves like a story.

For that reason, nothing else in the set sounds quite like Blanche-Neige. As with Parages and Symphonie, Les palpitations de la forêt, from 1985, includes several recognizable snippets among its battery of vibrations, but all the drama consists in the way those snippets are transformed, not in what they represent. The same can be said of 1979’s Entre terre et ciel. In these shorter pieces (still almost half an hour long) Lejeune steps out of the role of director and into the role of scientist. He places his material under a microscope, analyses the forces at play, then smashes everything to atoms, stretching some sounds to oblivion and restoring others to a semi-familiar state. The crux of the music consists in the elemental features revealed by this process: space, time, density, frequency, repetition, variation, volume, and memory all come to the fore; representation, melody, and narrative recede into the background. The landscapes and human references are still present—small streams, duck calls, muted fireworks, and so on—but they’re at the service of these building blocks.

Other composers from the GRM have used similar techniques in their work, as the recent glut of GRM reissues can attest. Bernard Parmegiani, Luc Ferrari, Jean-Claude Risset, and many others experimented with pre-recorded and acousmatic sounds, using them to play with form and to extend their musical vocabulary to regions far beyond the reach of acoustic instruments and traditional notation. In that sense, Jacques Lejeune’s music is part of an experimental tradition that took root in France during the 1940s. He learned his craft from the musicians and inventors responsible for its development and, to some degree, carried their interests and concerns into his own work. But his treatment of images and his focus on the theatrical and dramatic potential of musique concrète make him unique.

By gathering of all these pieces into one place, Robot has emphasized that uniqueness in a way that a single LP release, or even a triple gatefold deluxe LP release, couldn’t. The chronological presentation of Lejeune’s work, in combination with the remastered audio and uninterrupted playback, makes approaching and appreciating the music easier. The book of poetry and the program notes, despite their sometimes labyrinthine and overwrought language, do the same. The result is a smartly presented, perfectly focused snapshot of one of the GRM’s lesser known members, one that has long deserved such a considerate, thorough, and excellent retrospective.

samples:

- "The Icarus Cycle," from Parages

- "The Hunter's Race Dragging Snow White," from Blanche-Neige

- "Animated," from Symphonie au bord d'un paysage