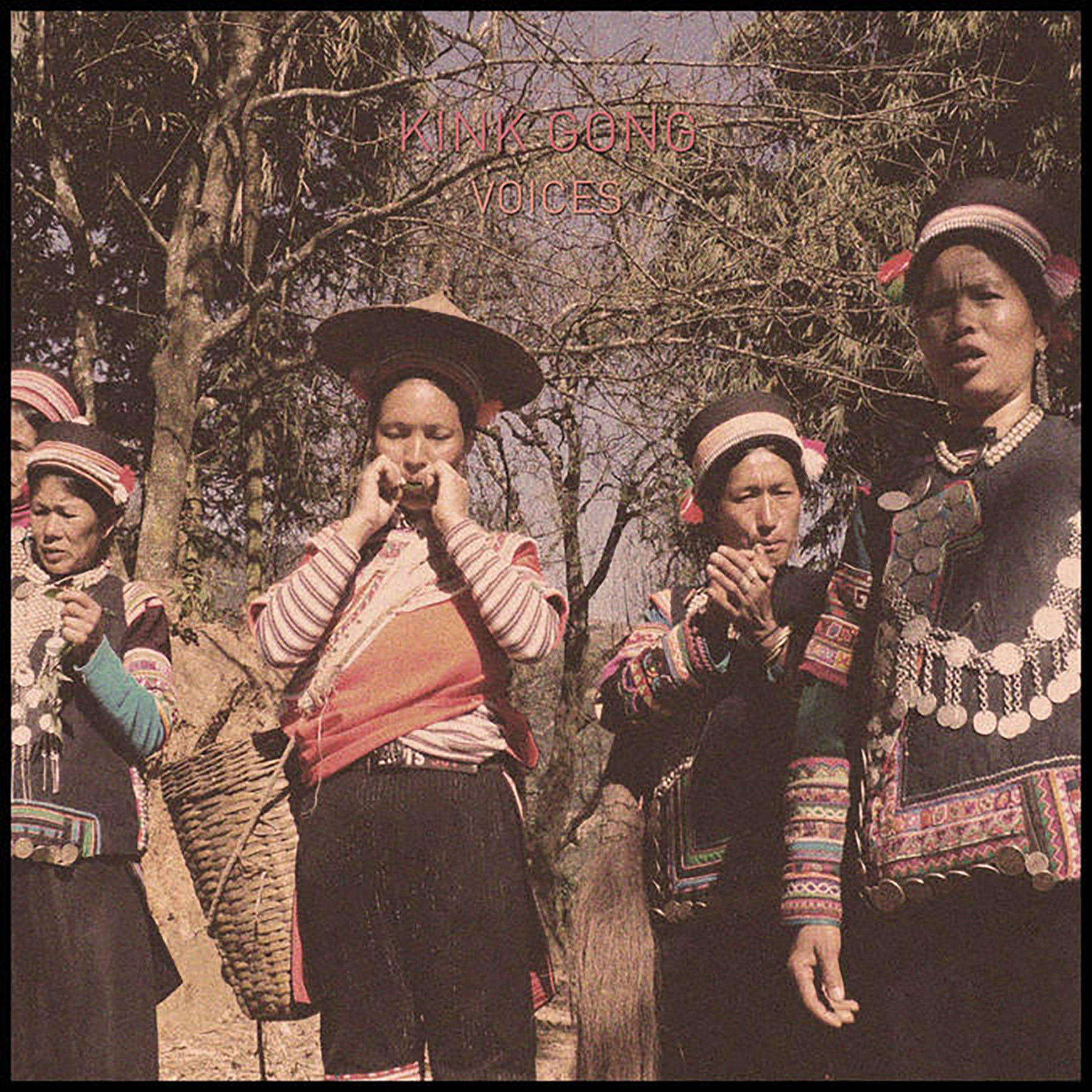

Kink Gong, "Voices"

Laurent Jeanneau's work as Kink Gong has been one of the most compellingly quixotic and unique projects in underground music for almost two decades, but I have only recently begun to scratch the surface of his mountain of work. He is probably best known as a prolific ethnomusicologist, occasionally surfacing on Sublime Frequencies. He has also self-released over 150 collections of ethnic minority music recorded during his many travels throughout Africa, China, and Southeast Asia. Naturally, that restless curiosity has made a deep impact on Jeanneau's own sensibility as an artist, resulting in a series fairly uncategorizable collage-based soundscape albums like this landmark 2013 release. At the root of Voices are a host of recordings of indigenous vocalists made in China, Vietnam, and Laos, but Jeanneau ingeniously transforms them into a haunting, otherworldly, and timeless vision that blurs the boundaries of tradition, experimentation, art, and reality.

Laurent Jeanneau's work as Kink Gong has been one of the most compellingly quixotic and unique projects in underground music for almost two decades, but I have only recently begun to scratch the surface of his mountain of work. He is probably best known as a prolific ethnomusicologist, occasionally surfacing on Sublime Frequencies. He has also self-released over 150 collections of ethnic minority music recorded during his many travels throughout Africa, China, and Southeast Asia. Naturally, that restless curiosity has made a deep impact on Jeanneau's own sensibility as an artist, resulting in a series fairly uncategorizable collage-based soundscape albums like this landmark 2013 release. At the root of Voices are a host of recordings of indigenous vocalists made in China, Vietnam, and Laos, but Jeanneau ingeniously transforms them into a haunting, otherworldly, and timeless vision that blurs the boundaries of tradition, experimentation, art, and reality.

The opening "Baozoo Khen" is the most sublime and powerful expression of Kink Gong's transformational wizardry on the album, as Jeanneau collages vocals from two women and a man into an eerily beautiful mass chorus of unusually harmonizing drones.There is also a backdrop of slowed-down mouthorgan, but the true brilliance and artistry of the piece lies how the voices endlessly converge and dissolve, hypnotically seesawing between their own wandering melodies and a single haunting, sustained chord.It is extremely simple and absolutely perfect in its unearthly, ritualistic reverie.Wisely, Jeanneau does not attempt to maintain that level of intensity for the rest of Voices, but he does masterfully deepen the spell, expanding his emotional and textural palette further with each new piece.In the following "Ar Mir Sanq Paq Aq Li," an Akha woman amiably and animatedly delivers a singsong monologue over gently, rippling bed of Jeanneau's lute playing.The effect is quite a dreamlike one, as the underlying music gradually evolves from a languorous sense of suspended animation to a multilayered cacophony of decontextualized voices, pointillist strings, and jabbering electronics.The first half of the album draws to a close with another highlight in the form of "Cym Wu Khmu," which ingeniously marries the visceral clatter of a Buddhist percussion ensemble with the playfully chattering voice of a Khmu woman.The percussion is impressively heavy and stomps relentlessly forward, yet the warbling and cheery voice in its midst creates an endearingly ambiguous mood.

The second half's pleasures are a bit more abstract, thought they are no less unique and inventive.The side begins with "3 Hani Pipa," which is probably the album's most curious and overtly experimental piece.Ostensibly, it is a collage of three different songs, but it is impossible to tell where one song ends and another begins or even which parts are actually from a song.Instead, it is sounds like an insistently strummed lute beneath a surreal chaos of hooting and chanting that resembles a raucous and unruly parade.The following "Sixian Miao Choir" is another lute piece of sorts, but it seems heavily processed and resembles overlapping recordings of someone violently playing a stand-up bass.While the sounds of the titular choir do drift through the proceedings, the overall impression is more like a feral and unhinged free-jazz performance (particularly when the "strangled balloon" howls burst onto the scene). The closing "Haoshendd" continues the cavalcade of disorienting surprises beautifully, as Jeanneau transforms the sounds of a lusheng (a Hmong pipe instrument) into a queasily blurred impressionist haze.Interestingly, it is a piece that lacks any recognizable voices, which makes it an odd choice for the final act of an album entitled Voices.It is also the only piece that sounds like it could have been a Kink Gong solo creation, as almost all melody or regional character has been sanded away to leave only subtly a discordant fog of drones.I suppose that makes it the album's least compelling piece, but it is nevertheless very effective at ending the album on an enigmatic and eerie note.

On one level, Voices stands with Harappian Night Recordings' The Glorious Gongs of Hainuwele as one the great recent masterpieces of ethnological forgery, as it is exotic, absorbing, and vividly realized in all the right ways.On a deeper level, however, it is more like a loving homage to the regional cultural traditions of the Laotian, Vietnamese, and Chinese villages that Jeanneau spent time in.With Voices, Jeanneau does not impose himself or appropriate ethnic minority cultures so much as he celebrates their vanishing traditions.While his transformations are certainly significant and occasionally dramatic, they are largely self-effacing ones that serve primarily to amplify and focus the existing attributes of the raw material: the emotions and performances in this album feel real, honest, and direct.Jeanneau's artistry lies primarily in his unerring intuition for recontextualizing these many voices in a way that is alluring to adventurous ears outside of rural Southeast Asia, yet does not sacrifice or betray their essence.That is an admirable approach and all the more so because it worked so beautifully: Voices is a wonderfully strange and multifaceted suite of songs that feels like a valiant attempt to convey everything that is joyful, dark, playful, and mysterious about being alive in a single piece of art.

Samples can be found here.