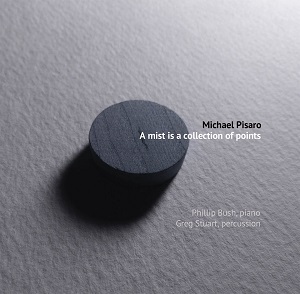

Michael Pisaro, "A Mist Is a Collection of Points"

After seeing it performed by Phillip Bush, Greg Stuart, and Joe Panzner at the Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater in downtown Los Angeles, the complexity in Michael Pisaro’s A Mist Is a Collection of Points cracked open. Scored for piano, percussion, and sine tones, the recorded version of A Mist presents itself transparently as a three-part composition with clear melodies and sharp edges. The piano is prominent, the sine tones thin and exact, the cymbals and crotales metallic, concentrated, centered. Their sounds are, in some ways, measured and containable, the opposite of a mist, which slips past the senses and confuses them. But watching Greg Stuart bow his crotales in the first section, seeing him react to Phillip Bush’s playing in the third, and searching for the places where the sine tones began and the acoustic resonance ended—that displaced and de-centered the entire piece. It turned its apparently fixed points into movable objects and transformed the music into a suspension of atoms and waves, detectable, though masked, in the superbly recorded and mastered document released by New World Records.

After seeing it performed by Phillip Bush, Greg Stuart, and Joe Panzner at the Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater in downtown Los Angeles, the complexity in Michael Pisaro’s A Mist Is a Collection of Points cracked open. Scored for piano, percussion, and sine tones, the recorded version of A Mist presents itself transparently as a three-part composition with clear melodies and sharp edges. The piano is prominent, the sine tones thin and exact, the cymbals and crotales metallic, concentrated, centered. Their sounds are, in some ways, measured and containable, the opposite of a mist, which slips past the senses and confuses them. But watching Greg Stuart bow his crotales in the first section, seeing him react to Phillip Bush’s playing in the third, and searching for the places where the sine tones began and the acoustic resonance ended—that displaced and de-centered the entire piece. It turned its apparently fixed points into movable objects and transformed the music into a suspension of atoms and waves, detectable, though masked, in the superbly recorded and mastered document released by New World Records.

Attendance of a live performance isn’t a prerequisite for enjoying A Mist, but visualizing it doesn’t hurt. The November 18th Los Angeles debut looked like this: Phillip Bush sat stage right and away from the audience, his grand piano open for inside manipulation. At stage left was a vibraphone, also set back from the audience. Front and center were four cymbals placed on the ground atop newspapers, a set of crotales, one of which hung from a string, and a pair of music stands laid flat to hold two containers of rice.

Stuart started the concert there, seated with a bow that he used to tease the crotales. Judging by the recording alone, the sine waves might as well have come from the stage too. They are omnipresent and omni-directional, originating from nowhere in particular and cutting across every aspect of the piece. Live, they were generated by Joe Panzner (who mastered this album) and projected from speakers throughout the theater. He was seated behind the audience, emphasizing the ubiquity and anonymity of the resonance that is one of the works’ central features.

As the music begins and Bush strikes the piano’s keys and strings, a series of high-pitched sine tones arise. Stuart selects a crotale and bows it. When he does, the sine waves wobble in the air. It seems obvious that Greg is affecting their sound, playing a tone very close to the one generated by the computer off stage. Yet, as he returns the crotale back to the table, further interference undulates throughout the room. Greg selects another, larger crotale. He bows that one, the sine waves change again, and again he stops only to reveal that the sine waves are still teetering between frequencies, beating and becoming more unstable. Are the sine waves changing and multiplying of their own accord, or is Stuart responsible for their instability?

During this interplay, Bush is steadily building a drone, holding the sustain pedal down and playing one melody after another. The attack of the hammers on the strings are definite and strong, the ensuing hum a layer of rhythm pulsing against the pronounced percussive character of the piano. These two streams bleed together and the two central points on the stage, Phillip and Greg, slowly lose their place. As in a mist, where locations and details become fuzzy, the musicians themselves lose their locality.

From time to time during the show, Stuart appeared to bow his instruments without creating a sound. His actions were subsumed into the points of harmony and reflection shimmering around him. These interactions are there on the recording too, clear as can be once one knows to look for them. The difficulty in recognizing them has more to do with the identity of the instruments, with their construction, than anything else. The piano has a sharp attack throughout. The crotale splashes at the end of the first section are clear-cut, as are the voices of the vibraphones and cymbals in the second and third sections. None of them are placed in one channel or the other, nor should they be, but the visual sense of position helps to recalibrate the ears for the effects they produce together. With Joe missing, with Greg getting lost in the exchange of what Jennie Gottschalk’s excellent liner notes call shadow tones, and with Phillip’s subtle distortion of time and space at the keyboard, orientation and confusion slowly gain significance, replacing that feeling of solidity and definiteness.

The second and third parts emphasize that turbulence in different ways, with lyrical phrases, instrumental mirroring, and with a dramatic finale that sees Greg dropping rice onto cymbals, first in heavy streams, then in slow, uneven bursts, until one by one, the piano, sine waves, and percussion take shape, just on the edge of silence. They haven’t exactly disentangled, it’s more like the music offers a brief image of them before they float away with the mist. The forces that hold A Mist together inhere the decisions the performers make, not necessarily in the score, which only suggests the possibility of coherence. There is a symmetry in the way the audience responds as well. Making sense of the confusion necessitates careful listening and navigating the piece’s many collisions as they drift, drawing patterns and disorder into the same space.

samples: