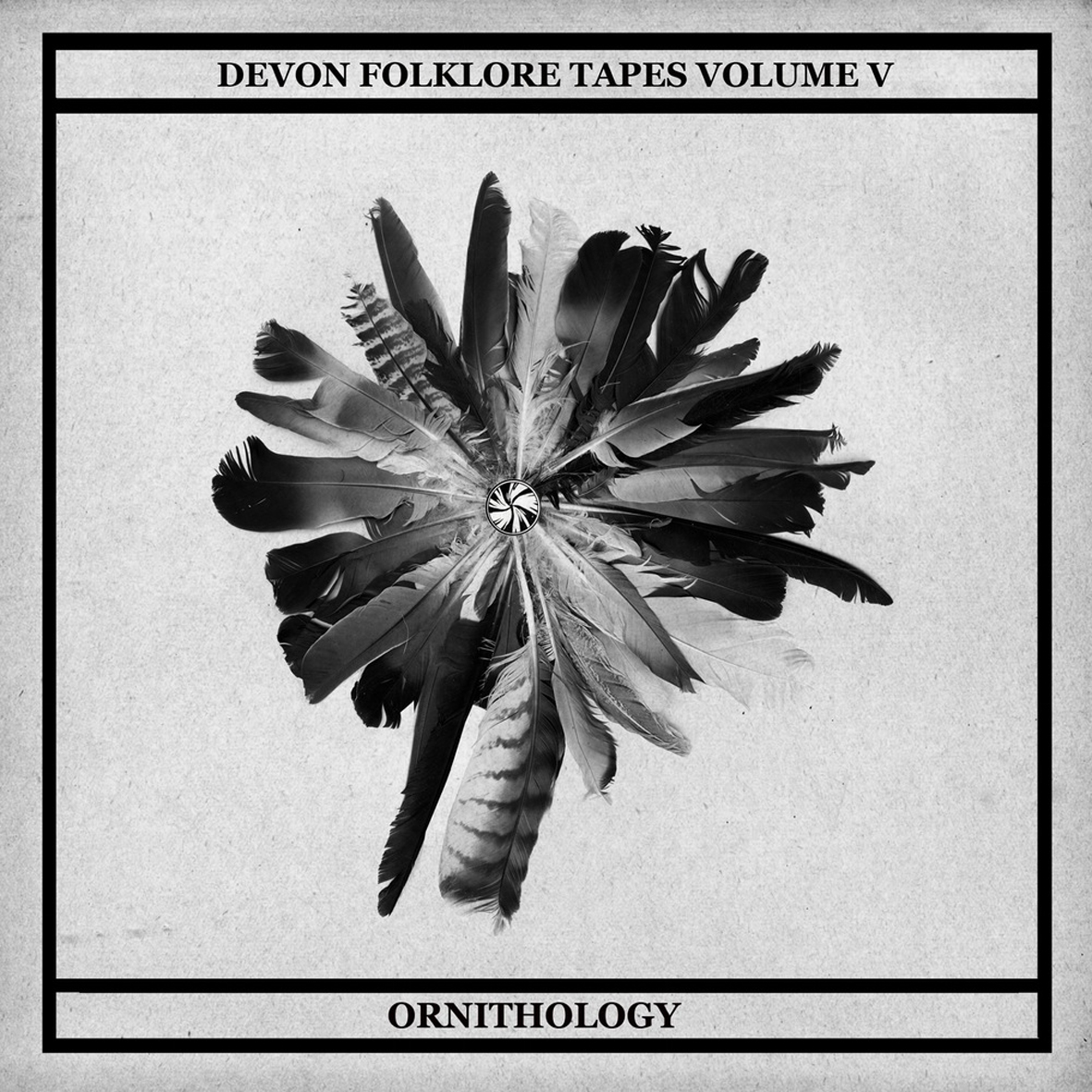

"Devon Folklore Tapes Volume V: Ornithology"

Folklore Tapes has quietly been one of the most singular and fascinating labels around for the last several years, a secret that they have managed to keep fairly well-concealed with their hyper-limited, hand-made and elaborate editions that tend to disappear quite quickly.  A handful of them eventually surface on Bandcamp, but most do not: Folklore Tapes releases are nothing if not elusive and ephemeral.  Thankfully, some of the more classic releases gradually get reissued, such as this one (which had an initial run of just 30).  This considerably larger (and newly vinyl-ized) reissue has an interesting twist, however, as the lengthy Children of Alice piece from the original has been replaced by three atypical new pieces from guitarist Dean McPhee.  Given that Children of Alice is comprised of the surviving members of Broadcast, that news will likely break a few hearts, but the two playfully hallucinatory soundscapes from the mysterious Mary Arches scratch quite a similar itch.

Folklore Tapes has quietly been one of the most singular and fascinating labels around for the last several years, a secret that they have managed to keep fairly well-concealed with their hyper-limited, hand-made and elaborate editions that tend to disappear quite quickly.  A handful of them eventually surface on Bandcamp, but most do not: Folklore Tapes releases are nothing if not elusive and ephemeral.  Thankfully, some of the more classic releases gradually get reissued, such as this one (which had an initial run of just 30).  This considerably larger (and newly vinyl-ized) reissue has an interesting twist, however, as the lengthy Children of Alice piece from the original has been replaced by three atypical new pieces from guitarist Dean McPhee.  Given that Children of Alice is comprised of the surviving members of Broadcast, that news will likely break a few hearts, but the two playfully hallucinatory soundscapes from the mysterious Mary Arches scratch quite a similar itch.

I certainly do not envy Dean McPhee, as stepping in as the replacement for the sole and rarely heard recording of James Cargill's post-Broadcast project is quite a tall order.  Fortunately, that departed piece is slated to be included in the group's formal debut, so it has not permanently disappeared and all is well.  More importantly, McPhee is a rather unique artist in his own right, so I am always eager to hear new work from him.  In this case, the new work is a three-song suite entitled Avian Dream Songs ("The Robin," "The Nightingale," and "The Blackbird").  I do not have the accompanying book, unfortunately, so I remain regrettably ignorant about each bird's significance in Devonshire lore.  However, I do know that crows are shapeshifters, magpie calls are an ill-omen, and that jackdaw cackles "betray runes of rut so unseemly a libertine would blush."  I would love to someday hear a jackdaw-themed Dean McPhee album, but he opted more for a serene and meditative feel with these pieces rather than going for raw, full-on sex this time around.  In any case, all three pieces are languorous, lovely, and unhurried improvisations over chirping and cooing field recordings of birds.  Of the three, "The Nightingale" is probably my favorite and the most substantial departure from McPhee's usual fare, unfolding as a gorgeously subdued and melancholy flow of volume swells.  I also quite enjoyed the tranquil and sun-dappled "The Blackbird," as it feels the most like an organic interplay with McPhee's unwitting avian collaborators.

I have absolutely no idea who is behind the "Mary Arches" guise, but I definitely know that I like them.  Stylistically, both halves of "The White Bird of the Oxenhams" strike a beautiful balance between collage, kitsch, and hauntology.  Naturally, there are plenty of birds involved here as well, though the specific type of bird that kept turning up to foretell premature deaths in the hapless Oxenham clan is up for debate.  "The Room" initially seems like a rather dark piece, opening with some wonderfully dense and eerie drones and evolving into a dissonant music box motif, but it eventually takes a rather cartoonish turn with some loud snoring and plinking percussion.  It is quite a hard piece to get a handle on, covering some quite strange and varied ground over its twelve minutes.  "The Reverie" is a bit more consistently strong and immediately gratifying, as it is built upon a beautifully wobbly and swooping synth melody over a lazily jaunty groove.  There are also plenty of squelching and crunching field recordings in the periphery to make it even more evocative.  At some point, however, that all fades away and the piece sounds like a crackling old recording of a vampire blasting away on a pipe organ in his lonely castle.  Anything resembling genuine darkness is mischievously undercut with plenty of random boinging noises though, along with some weirdly hollow yet festive percussion that sounds like the missing link between Einstürzende Neubauten and Les Baxter.  Then, bizarrely, it all winds to a close with a rippling and dreamy coda of almost tropical-sounding guitars.

Needless to say, the deranged and kaleidoscopic B-movie kitsch of Mary Arches makes for a very counterintuitive pairing with the understated beauty of Dean McPhee’s trio of avian dreamscapes, but it somehow perversely works as a whole.  While the quiet simplicity and understated melodicism of McPhee's songs admittedly took a few listens to fully seep into my consciousness, they eventually became my favorite part of the album and provide a very necessary, sincere, and earthy counterbalance to the carnival of absurdity that follows.  Of course, I enjoy that aspect of the album too, as there is plenty of fun and an occasional brush with genius amidst all the gleefully wonky madness, even if the "Oxenham" pieces are a bit too long, erratic, and uneven to quite work on their own.  Ultimately, it is McPhee's subtly haunting "The Nightingale" that stealthily dominates the album and comes closest to evoking the eerie witchery and timelessness of the stories that inspired this release, but there is plenty of strange, sublime, and mindwarping terrain to explore around it.

Samples: