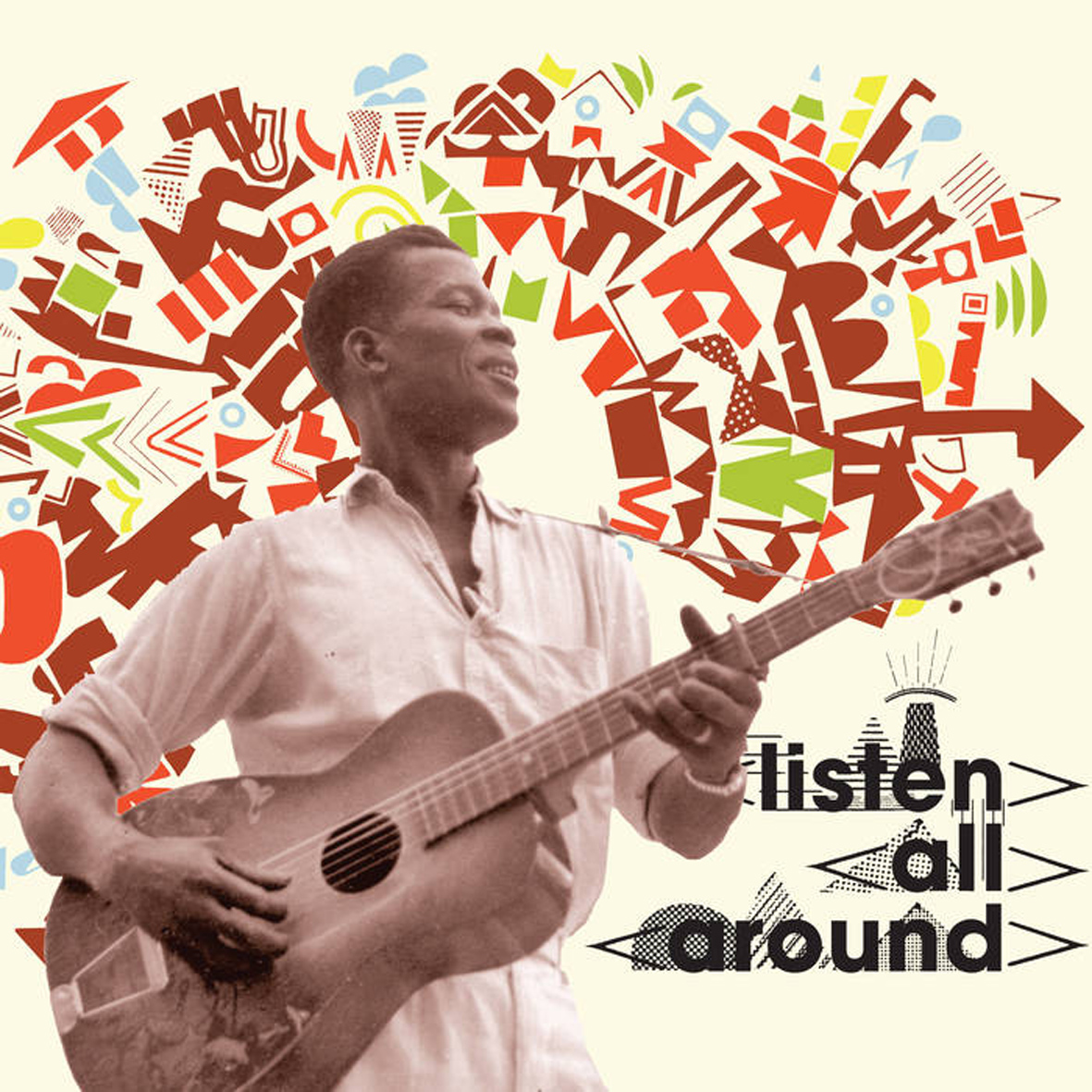

"Listen All Around: The Golden Age of Central and East African Music"

There are a number of great labels unearthing and breathing new life into forgotten treasures these days, but it is truly rare for anyone to match Dust-to-Digital when it comes to presentation and sheer comprehensiveness. Each major release feels like an event years in the making, certain to send at least one circle of obsessive music fans scavenging for additional extant releases from an eclectic array of previously unknown or obscure artists. This latest opus is an especially big hit with me, collecting a remastered trove of '50s East and Central African rumba recordings by South African/English musicologist Hugh Tracey. I had no doubt that these recordings would be unique and historically important, but I was legitimately blindsided by how incredibly fun these songs can be, often resembling a raucous, inebriated, and Latin-tinged street party where everyone knows all the words to every song and nearly everyone seems to have inexplicably brought along a kazoo.

There are a number of great labels unearthing and breathing new life into forgotten treasures these days, but it is truly rare for anyone to match Dust-to-Digital when it comes to presentation and sheer comprehensiveness. Each major release feels like an event years in the making, certain to send at least one circle of obsessive music fans scavenging for additional extant releases from an eclectic array of previously unknown or obscure artists. This latest opus is an especially big hit with me, collecting a remastered trove of '50s East and Central African rumba recordings by South African/English musicologist Hugh Tracey. I had no doubt that these recordings would be unique and historically important, but I was legitimately blindsided by how incredibly fun these songs can be, often resembling a raucous, inebriated, and Latin-tinged street party where everyone knows all the words to every song and nearly everyone seems to have inexplicably brought along a kazoo.

Few, if any, Westerners can claim to have done as much to bring African music to the world as Hugh Tracey, as he founded the International Library of African Music (ILAM) and made twelve separate treks into sub-Saharan Africa to collect instruments and record local musicians.Based on the recollections of his wife Peggy in the accompanying booklet, these trips were often far from pleasant, as the bad roads, rugged accommodations, car breakdowns, and illnesses inherent in such an endeavor made it quite hard to enlist a willing team.Also, people were not exactly clamoring to join the Traceys in the first place, as being so far ahead of the curve was a lonely life: having an intense passion for African music in the early '50s branded Hugh as a "crank" or a "dreamer" in most respectable circles.Amusingly, he also later took flak from the other side, as more "serious" ethnomusicologists took issue with some of his recording/editing preferences and his "staging" of traditional performances.According to Peggy, the "jackals" from the record company (Gallo) also pressured Tracey to focus on the more marketable "town" or popular music scenes, whereas he was much more interested in indigenous/traditional fare.It would probably break Hugh's heart a bit to see that so much "town" music wound up on this collection, but the jackals were surprisingly prescient, as that buoyant mélange of styles has aged remarkably well.I am completely out of my depth in trying to identify and follow the various improbable threads that found their way into these songs, but the most prominent influences to my ears tend to be Latin American and Caribbean in nature, though Hawaiian, Indian, and Arab influences are sneakily rampant as well.

Unsurprisingly, "town" music is quite a wide category in the context of this album, as Tracey found significant differences in styles as he and his crew traveled from region to region.That variety is best illustrated by the three versions of a single song entitled "Nimepata Mpenzi, Mtoto Mdogo, Mzuri, Simwachi (I Got a Young, Beautiful Girl that I Won't Leave)" recorded in Tanganyika and Malawi.Notably, it is one of the album's finest songs, yet each version takes a very different direction despite adhering to roughly the same melody and lyrics.In the Dar es Salaam version, the piece is a lurching, percussion-heavy sing-a-long with a drunken-sounding central theme played on violin and kazoo.In the Mawanza version (my favorite), the central melody is a gorgeously bittersweet swirl of flutes that harmonize and intertwine sensually.Elsewhere, in Malawi, the piece sounds like it was performed by a mandolin-wielding mariachi band.As if to pointedly emphasize the beguiling eclecticism of '50s African rumba still further, that triptych is followed by "Chineno," a wonderful piece by Dar es Salaam ballroom dance ensemble Merry Black Birds that resembles some sort of Thai or Arabic surf oddity that I would expect to encounter as the centerpiece of a Sublime Frequencies collection.My favorite piece on the album comes from the Congo, however, as Coast Social Orchestra's "Nali Kisafiri" is a radiant and rolling delight that sounds like a classic New Orleans jazz standard enlivened with a healthy dose of Cuban percussion and highlife rhythm.

Listen All Around is not exclusively populated by lively dance ensembles of varying competence and ramshackleness, however, as compiler Alex Perullo peppers the collection with entertaining oddities and delightfully rough-edged performances from Tracey's vast archive of ILAM recordings.Three such highlights are "Soko Olingi Na-Boma (If You Want to Kill Me)," "Kwa Jinsi Ninavyokupenda (How I Love You)," and "Mangwasi."The latter, a "passionately sung love song by a young Tukuyu musician" is among the rawest and most endearingly unhinged-sounding pieces on the album, as the melody is delivered in wonderfully motor-mouthed and hammy fashion over some three-chord jangling guitar, arguably anticipating punk by at least two decades."If You Want to Kill Me" is fun in a very different way, unfolding as a similarly rapid-fire vocal performance, but bolstered by plenty of backing refrains, lively and clattering hand percussion, and whistled melodies that seem to amusingly wander in and out of tune.Lastly, "How I Love You" is one of the album's true masterpieces, resembling a tipsy and lurching Latin brass band parade trailed by a wake of celebrants adding their own embellishments of honking kazoos and clinking bottles.That is actually just what the amateur-populated Dar es Salaam jazz band sounded like normally, which only earns them a deeper place in my heart.More than anyone else on the album, that band of spirited amateurs captures both what makes Listen All Around such a great collection and why Tracey was so captivated by the sounds of the region: even the least polished ensembles feel like a vibrantly alive and rhythmically inventive collection of cross-cultural magpies with a singular intuition for taking the best parts of literally anything they have heard and seamlessly making it their own.A lot of newly reissued ethnomusicological finds from the 1950s and earlier feel more like school than entertainment or pulsing, unfiltered life to me, but Listen All Around is a truly wonderful exception.

Samples can be found here.