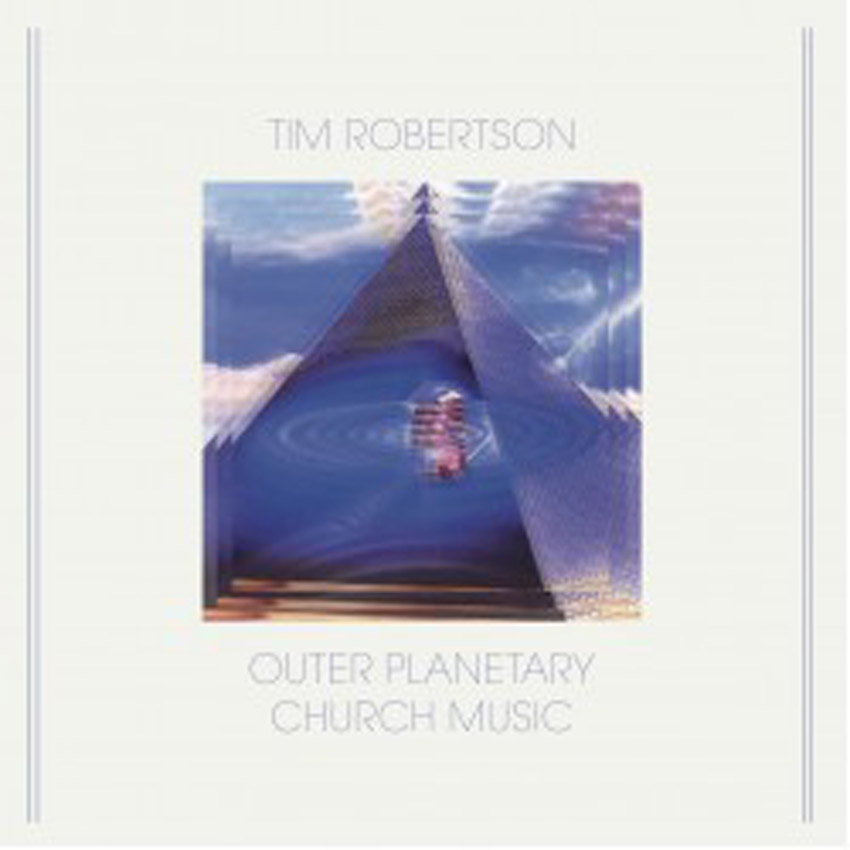

Tim Robertson, "Outer Planetary Church Music"

I hate to throw around the woefully overused phrase "great lost album," but Aguirre stumbled onto something quite amazing with this record.  I have no idea if Tim Robertson is still involved in music at all these days, but in his teens he was a church organist who traveled the world with his missionary parents.  After returning to Barcelona following a few years in Africa, he bought a four-track and spent two years obsessed with the idea of creating music "for future temples on Neptune and Saturn."  Eventually, that bizarre phase passed and Tim threw out all of his recordings except for two tapes, which he gave to his (presumably bewildered) parents as a gift.  Roughly 20 years later, those surreal experiments have now publicly surfaced thanks to a chance meeting in a thrift store.  This is "outsider" music for sure, but its guileless simplicity and elegiac beauty nevertheless place it very high in the pantheon of early New Age fringe-dwellers.

I hate to throw around the woefully overused phrase "great lost album," but Aguirre stumbled onto something quite amazing with this record.  I have no idea if Tim Robertson is still involved in music at all these days, but in his teens he was a church organist who traveled the world with his missionary parents.  After returning to Barcelona following a few years in Africa, he bought a four-track and spent two years obsessed with the idea of creating music "for future temples on Neptune and Saturn."  Eventually, that bizarre phase passed and Tim threw out all of his recordings except for two tapes, which he gave to his (presumably bewildered) parents as a gift.  Roughly 20 years later, those surreal experiments have now publicly surfaced thanks to a chance meeting in a thrift store.  This is "outsider" music for sure, but its guileless simplicity and elegiac beauty nevertheless place it very high in the pantheon of early New Age fringe-dwellers.

Admittedly, Robertson’s story sounds like it has all the makings of a hoax, but Aguirre seems like an extremely unlikely label to perpetuate such a thing.  Also, the provenance of Outer Planetary Church Music is not particularly important for its enjoyment, as it is a legitimately appealing and unusual album regardless of when it was recorded or by whom.  That said, it is noteworthy and amusing that Tim definitely did not allow his imagination to run too wild when he was dreaming these pieces up, as the future music of Neptune apparently shares a staggering amount of common ground with the church music of contemporary Earth.  For example, it looks like it will be primarily played on an organ in 4/4 time using common Western musical scales.  Nevertheless, Tim did make some significant innovations within those very earthbound constraints.  On the first untitled piece, for example, he slows down to an eerily shimmering reverie embellished with ghostly wordless vocals and floating harmonies, all of which are further enhanced by the murkiness and hiss of the recording.  The building blocks of conventional church music may be present, but they certainly do not sound like any religious music that I would expect to hear outside of an especially cool and psych-minded cult.

Unfortunately, Tim also occasionally delves into twinkling, major key vapidity at times, as he does with the mercifully brief second piece (which my imaginary "cool" cult would no doubt scoff at).  On balance, however, Robertson is inspired far more often than he is not.  He is at his best when he is at his bleariest and most bittersweet, as he is with the third piece.  Also, Tim makes a definite virtue of simplicity, allowing his strong and melodic motifs to unfold in an unbroken, hypnotic stream.  In lesser hands, the lack of transitions or multiple movements would be a distinct shortcoming, but Tim adeptly compensates with an intuitive knack for timing, flow, and texture.  Though none of these seven pieces ever quite blossoms into something noticeably different than their initial theme, all tend to build into something appealingly warm, layered, and subtly hallucinatory nonetheless.  Being a "one idea equals one song" artist is perfectly fine if the artist in question knows how to get the most out of a given motif, which Tim clearly does.

Other highlights include the final two pieces (both untitled, of course).  The first is kind of a sleepy, languorous reverie, but it is beautifully enhanced by a haze of oscillating harmonies and overtones, some of which are likely unintended gifts from Tim's lo-fi, analog home-recording set-up.  The similarly excellent closing piece, on the other hand, is built upon a couple of sonorous, melancholy chords that are gradually subsumed by layers of twinkling arpeggios and woozy swells.  Sadly, it fades out unexpectedly early, but it is certainly great while it lasts.  While it is admittedly perplexing that Robertson decided to truncate one of his strongest compositions, it feels a bit ridiculous to critique the decision-making process of a man who set out to create church music for Saturn.

As far as I am concerned, Outer Planetary Church Music’s greatest flaw is actually an asset: it definitely feels like a primitively recorded and sketch-like suite of songs, but that adds weight to both the sincerity of the enterprise and the feeling that I am hearing something secret and special that was never meant to escape into the world.  That said, there are a couple of weaker pieces that I could have done without, but they are mercifully short.  I was actually far more troubled by the great songs not being quite as long as I would have liked.  Such quibbles are somewhat immaterial, however, as they are easily eclipsed by the fact that an otherworldly, improbable album like this even exists (and that it is actually remarkably good).