Podcast Episodes 754, 755, 756 (August 23) are live!

Feeling the heat of the dog days of summer, time has caught up with us once again so we bring you three new episodes of stuff from this year.

Episode 754 features brand new music from Major Stars, Softcult, Nobukazu Takemura, The Stargazer Lilies, Triple Five Sol, Lifeguard, Laibach (feat. Bjelo Dugme), The Colour Of Madness, The Egyptian Lover, Dale Cornish, and BlankFor.ms, Erik Griswold.

Episode 755 has new music from Holy Sons, claire rousay (feat. m sage), Edward Ka-Spel, KILN, Carolyn Fok, Christian Wallumrød, Cat Temper, Michele Andreotti, BJ Nilsen, Donna Regina, and Aki Onda, plus a classic from The Fall.

Episode 756 has new tunes Self Improvement, Bayun the Cat & Iouri Grankin, Gwenifer Raymond, Coatshek, Jim White, Kieran Hebden + William Tyler, Adrian Sherwood, A Grape Dope, David Donohoe & Kate Carr, and Natural Wonder Beauty Concept, and music from the vaults from Rousers, and The Body.

Thanks to Fabien for the photos for all three episodes. This one of volleyball from Carson Beach in Boston.

Get involved: subscribe, review, rate, share with your friends, send images!

Read more …

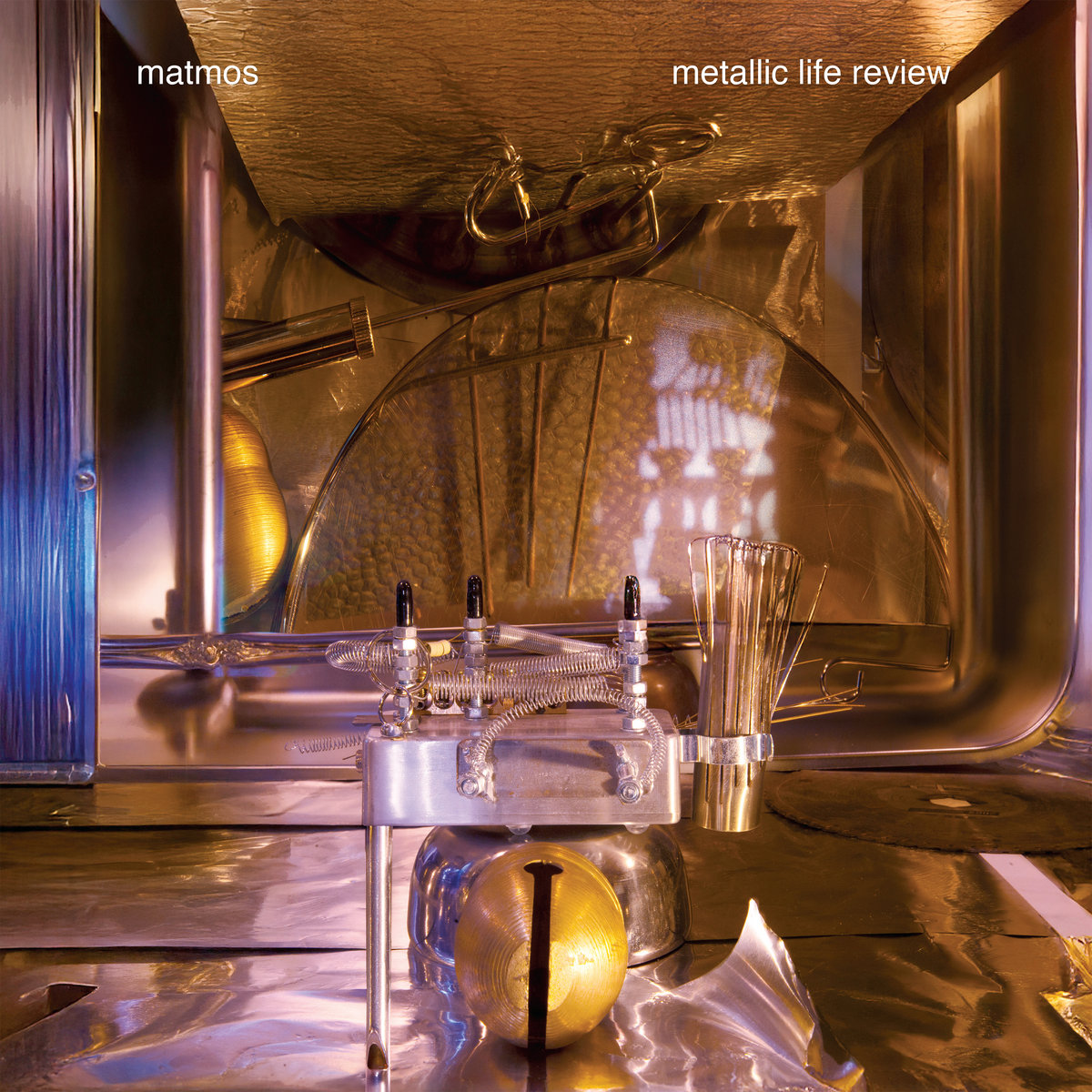

This is the debut full-length from the duo of Rachika Nayar and Nina Keith, who previously collaborated on a single back in 2021. Notably, I am a big fan of Nayar’s early guitar-centric releases (Our Hands Across The Dusk and Fragments), but she lost me a bit with the “maximalist synths, sub-bass, and Amen breaks” of her 2022 breakout album Heaven Come Crashing (I am definitely in the minority on that one). Consequently, I had some legitimate trepidation about where Nayar would head next. This is my first encounter with Nina Keith, however, and it definitely will not be my last. All bets are off when these two team up.

This is the debut full-length from the duo of Rachika Nayar and Nina Keith, who previously collaborated on a single back in 2021. Notably, I am a big fan of Nayar’s early guitar-centric releases (Our Hands Across The Dusk and Fragments), but she lost me a bit with the “maximalist synths, sub-bass, and Amen breaks” of her 2022 breakout album Heaven Come Crashing (I am definitely in the minority on that one). Consequently, I had some legitimate trepidation about where Nayar would head next. This is my first encounter with Nina Keith, however, and it definitely will not be my last. All bets are off when these two team up. This is the debut release from the Norwegian duo of Espen Friberg and Jenny Berger Myhre. The pair previously worked together during the recording of Friberg’s solo debut Sun Soon (Hubro, 2022), as Berger Myhre helped out with production and arrangements. During those sessions, the pair discovered that they shared a “playful, intentionally naive approach towards making art” and Flutter Ridder was born.

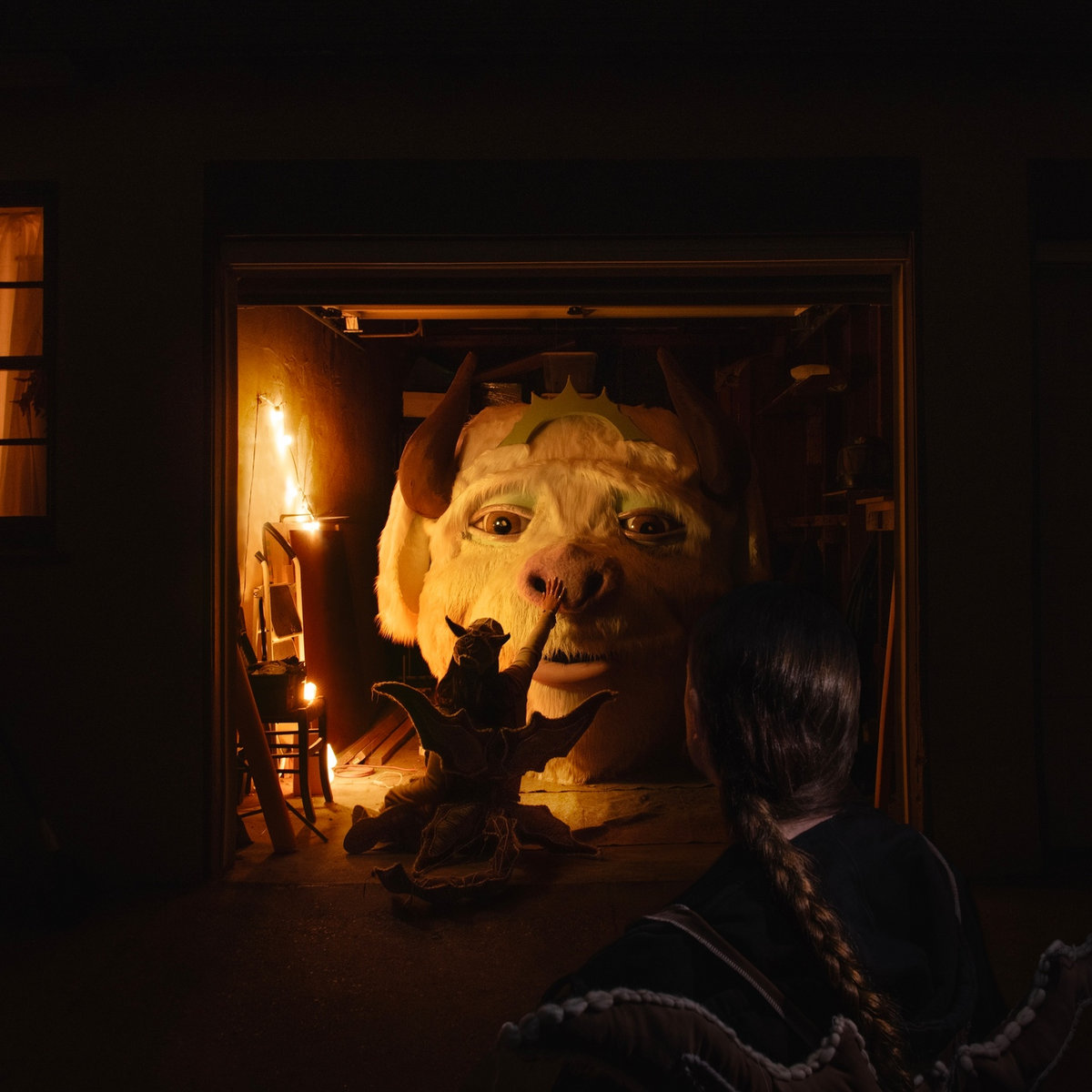

This is the debut release from the Norwegian duo of Espen Friberg and Jenny Berger Myhre. The pair previously worked together during the recording of Friberg’s solo debut Sun Soon (Hubro, 2022), as Berger Myhre helped out with production and arrangements. During those sessions, the pair discovered that they shared a “playful, intentionally naive approach towards making art” and Flutter Ridder was born. When I first learned about this release, I was stoked that Madeleine Johnston had enlisted Matt Jencik as a collaborator for the latest Midwife album, as I am a big fan of his 2019 album Dream Character. As it turns out, however, the actual situation was the reverse of that, as Jencik had decided to step outside his ambient drone comfort zone six years ago to record an album of vocal pieces centered around the theme of mortality. Things did not work out quite as planned, however, as Jencik first embarked upon this project with an entirely different collaborator. It feels like destiny that he ultimately wound up working with Johnston instead, however, as the two have a wonderfully complementary yin/yang relationship both stylistically (close mic’d basement 4-track intimacy vs. elegantly sculpted hiss and distortion) and philosophically (Jencik feels a desperate desire to hold onto everyone he loves, while Johnston sees the spectre of death as an “incentive to live more keenly and dearly”).

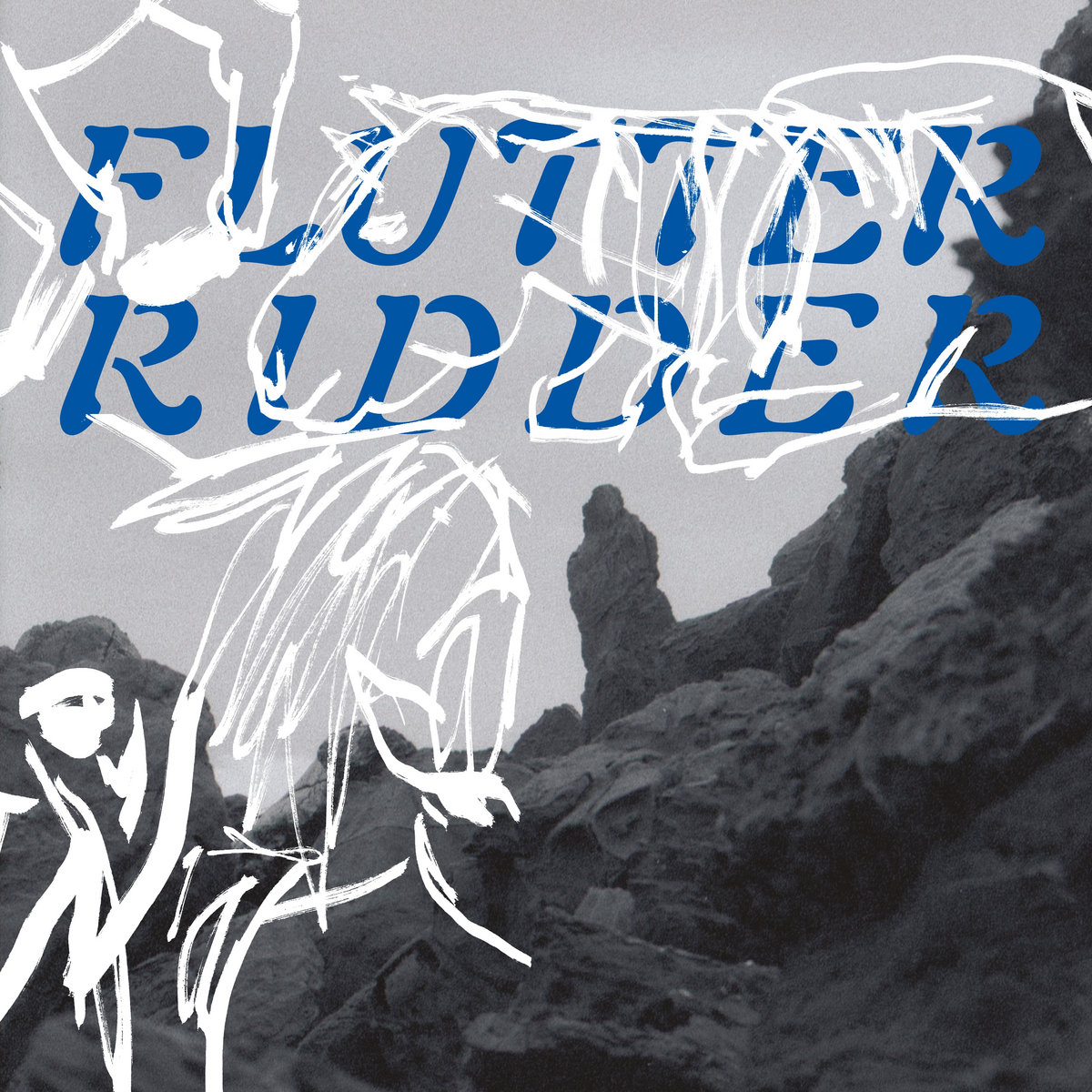

When I first learned about this release, I was stoked that Madeleine Johnston had enlisted Matt Jencik as a collaborator for the latest Midwife album, as I am a big fan of his 2019 album Dream Character. As it turns out, however, the actual situation was the reverse of that, as Jencik had decided to step outside his ambient drone comfort zone six years ago to record an album of vocal pieces centered around the theme of mortality. Things did not work out quite as planned, however, as Jencik first embarked upon this project with an entirely different collaborator. It feels like destiny that he ultimately wound up working with Johnston instead, however, as the two have a wonderfully complementary yin/yang relationship both stylistically (close mic’d basement 4-track intimacy vs. elegantly sculpted hiss and distortion) and philosophically (Jencik feels a desperate desire to hold onto everyone he loves, while Johnston sees the spectre of death as an “incentive to live more keenly and dearly”).  This latest release from the duo of M.C. Schmidt and Drew Daniel is billed as a “compressed fast-forward of Matmos’ career with a sonic parade of the metallic objects from their lives,” as they attempted to mimic the psychological phenomenon of “life review” that people experience during near-death experiences, but quixotically decided to do it exclusively through metallic sound sources. Naturally, that constraint resulted in quite an eclectic and interesting instrumental palette that ranges from “pots and pans from each member’s childhood” to metal reels used in the recording of iconic early musique concrète pieces at Paris's INA/GRM. Notably, however, this album is a bit less uncompromisingly purist than I expected, as the late Susan Alcorn contributed pedal steel to a couple of pieces (still technically metal though).

This latest release from the duo of M.C. Schmidt and Drew Daniel is billed as a “compressed fast-forward of Matmos’ career with a sonic parade of the metallic objects from their lives,” as they attempted to mimic the psychological phenomenon of “life review” that people experience during near-death experiences, but quixotically decided to do it exclusively through metallic sound sources. Naturally, that constraint resulted in quite an eclectic and interesting instrumental palette that ranges from “pots and pans from each member’s childhood” to metal reels used in the recording of iconic early musique concrète pieces at Paris's INA/GRM. Notably, however, this album is a bit less uncompromisingly purist than I expected, as the late Susan Alcorn contributed pedal steel to a couple of pieces (still technically metal though). On her first vinyl LP release, multidisciplinary artist Susana López presents four compositions that blend synths, field recordings, and other sounds treated into pure abstraction. Layered and processed, they are reassembled into compositions that are quite beautiful yet have an alien quality to them that makes them all the more engaging.

On her first vinyl LP release, multidisciplinary artist Susana López presents four compositions that blend synths, field recordings, and other sounds treated into pure abstraction. Layered and processed, they are reassembled into compositions that are quite beautiful yet have an alien quality to them that makes them all the more engaging. This debut release from young Cambridge, Massachusetts-based composer Gabriel Brady was apparently recorded in his dorm room with little more than a bouzouki, a violin, and a “compact modular synth setup,” but it often sounds like it could have been the work of a veteran and visionary tape loop artist. As far as I know, there were no actual tape loops involved in these recordings, but Brady ingeniously achieved a similar effect by feeding his acoustic instruments into his synth, which acted as a "sound chamber for further manipulation (loops, effects, textures).”

This debut release from young Cambridge, Massachusetts-based composer Gabriel Brady was apparently recorded in his dorm room with little more than a bouzouki, a violin, and a “compact modular synth setup,” but it often sounds like it could have been the work of a veteran and visionary tape loop artist. As far as I know, there were no actual tape loops involved in these recordings, but Brady ingeniously achieved a similar effect by feeding his acoustic instruments into his synth, which acted as a "sound chamber for further manipulation (loops, effects, textures).” I believe this album’s unusual title is a palindromic way to convey that it is intended as a spiritual sequel to 2019’s Tutti, as it certainly seems to continue the stylistic trajectory of its predecessor. Notably, however, Tutti was assembled from repurposed archival material to coincide with an exhibition whereas 2t2 is composed of entirely new material. Aside from that, the two albums are quite similar, as this one is also a blend of driving synthesizer vamps and moody ambient pieces. To my ears, this latest outing is not quite as strong as Tutti, as it is a bit lean on hooks, but Cosey certainly tries out a lot of interesting ideas (including some new techniques that emerged from her deep research into Delia Derbyshire’s archive). Some of those experiments are definitely more satisfying than others, but there is one killer new piece (“Never The Same”) that can easily hang with Cosey’s previous career highlights.

I believe this album’s unusual title is a palindromic way to convey that it is intended as a spiritual sequel to 2019’s Tutti, as it certainly seems to continue the stylistic trajectory of its predecessor. Notably, however, Tutti was assembled from repurposed archival material to coincide with an exhibition whereas 2t2 is composed of entirely new material. Aside from that, the two albums are quite similar, as this one is also a blend of driving synthesizer vamps and moody ambient pieces. To my ears, this latest outing is not quite as strong as Tutti, as it is a bit lean on hooks, but Cosey certainly tries out a lot of interesting ideas (including some new techniques that emerged from her deep research into Delia Derbyshire’s archive). Some of those experiments are definitely more satisfying than others, but there is one killer new piece (“Never The Same”) that can easily hang with Cosey’s previous career highlights. The latest opus from this Gdansk-based composer is the final part of dark trilogy of albums that began with 2013’s Liebestod and continued with 2017’s Rite of the End. According to Wesołowski, the three albums are united by themes of “existential matters such as love, death, decay” as well as “an apocalyptic and Promethean ultimate end.” Given that ambitious scope, it is no surprise that Wagner was a major inspiration for the previous installments, but this one is partially rooted in W.G. Sebald’s writings on “the nature of memory” and “how thoughts and desires overlap and mutate over time.” That “Sebaldian nature” is most prominently manifested in Wesołowski’s decision to sample his own sketches and unused recordings, but the elemental intensity of these pieces suggests that the shadow of Wagner still looms large in his vision.

The latest opus from this Gdansk-based composer is the final part of dark trilogy of albums that began with 2013’s Liebestod and continued with 2017’s Rite of the End. According to Wesołowski, the three albums are united by themes of “existential matters such as love, death, decay” as well as “an apocalyptic and Promethean ultimate end.” Given that ambitious scope, it is no surprise that Wagner was a major inspiration for the previous installments, but this one is partially rooted in W.G. Sebald’s writings on “the nature of memory” and “how thoughts and desires overlap and mutate over time.” That “Sebaldian nature” is most prominently manifested in Wesołowski’s decision to sample his own sketches and unused recordings, but the elemental intensity of these pieces suggests that the shadow of Wagner still looms large in his vision. This latest album from Guido Zen’s Abul Mogard alter ego marks both the debut of his Soft Echoes label and an interesting detour from his usual working methods, as he reworked unreleased material from past projects and texturally enhanced it with sounds culled from his late uncle’s collection of classical 78s.

This latest album from Guido Zen’s Abul Mogard alter ego marks both the debut of his Soft Echoes label and an interesting detour from his usual working methods, as he reworked unreleased material from past projects and texturally enhanced it with sounds culled from his late uncle’s collection of classical 78s. This latest speaker-straining salvo from the duo of James Ginzburg and Paul Purgas was fittingly debuted at the Tate Modern to accompany “a large-scale survey of the global history of art and technology” entitled Electronic Dreams. I say “fittingly” because Dissever both feels like a uniquely visceral and violent strain of high art and some kind of massive and menacing industrial installation. I suppose both of those things can be said about some previous emptyset albums as well, but this one is unquestionably more aggressively minimalist and driven by machine-like repetition. Notably, the conceptual inspiration behind that move was an interest in the intertwined evolutions of “cosmic rock, minimalism and electronic music” and late-20th century advances in production technology, so the duo went appropriately analog/retro with both their gear and recording techniques.

This latest speaker-straining salvo from the duo of James Ginzburg and Paul Purgas was fittingly debuted at the Tate Modern to accompany “a large-scale survey of the global history of art and technology” entitled Electronic Dreams. I say “fittingly” because Dissever both feels like a uniquely visceral and violent strain of high art and some kind of massive and menacing industrial installation. I suppose both of those things can be said about some previous emptyset albums as well, but this one is unquestionably more aggressively minimalist and driven by machine-like repetition. Notably, the conceptual inspiration behind that move was an interest in the intertwined evolutions of “cosmic rock, minimalism and electronic music” and late-20th century advances in production technology, so the duo went appropriately analog/retro with both their gear and recording techniques.  This latest opus from the Opalio brothers is a pair of single-sided art LPs devoted to two very different performances featuring the duo’s longtime collaborator Joëlle Vinciarelli (Talweg/La Morte Young). In classic Opalio fashion, The Secret of the Space Bubble was inspired by a vision that Roberto had of four astronauts performing in zero gravity. The lucky fourth astronaut in this case is Talweg’s other half (Eric Lombaert) and the combination of his virtuosic freeform drumming with Vinciarelli’s strangled flugelhorn partially steers things in a more Sun Ra-esque spaced-out free jazz direction than usual. There are, however, some other unique factors in play, as the Opalios exclusively used Vinciarelli’s collection of unusual and ancient instruments rather than their usual gear. Also, it was recorded using only two ambient mics to create a “vortex of sound” where all of the sounds and their reverberations were “centrifuged/blended together” to achieve the necessary “space bubble” effect.

This latest opus from the Opalio brothers is a pair of single-sided art LPs devoted to two very different performances featuring the duo’s longtime collaborator Joëlle Vinciarelli (Talweg/La Morte Young). In classic Opalio fashion, The Secret of the Space Bubble was inspired by a vision that Roberto had of four astronauts performing in zero gravity. The lucky fourth astronaut in this case is Talweg’s other half (Eric Lombaert) and the combination of his virtuosic freeform drumming with Vinciarelli’s strangled flugelhorn partially steers things in a more Sun Ra-esque spaced-out free jazz direction than usual. There are, however, some other unique factors in play, as the Opalios exclusively used Vinciarelli’s collection of unusual and ancient instruments rather than their usual gear. Also, it was recorded using only two ambient mics to create a “vortex of sound” where all of the sounds and their reverberations were “centrifuged/blended together” to achieve the necessary “space bubble” effect.